AGENCY:

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS.

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

This final rule updates the prospective payment rates, the outlier threshold, and the wage index for Medicare inpatient hospital services provided by Inpatient Psychiatric Facilities (IPFs), which include psychiatric hospitals and excluded psychiatric units of an inpatient prospective payment system hospital or critical access hospital. Additionally, this final rule revises and rebases the IPF market basket to reflect a 2016 base year and removes the IPF Prospective Payment System (PPS) 1-year lag of the wage index data. Finally, this final rule implements updates to the Inpatient Psychiatric Facilities Quality Reporting Program. These changes will be effective for IPF discharges beginning during the fiscal year (FY) from October 1, 2019 through September 30, 2020 (FY 2020).

DATES:

These regulations are effective on October 1, 2019.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

The IPF Payment Policy mailbox at IPFPaymentPolicy@cms.hhs.gov for general information.

Mollie Knight, (410) 786-7948 or Hudson Osgood, (410) 786-7897, for information regarding the market basket rebasing, update, or the labor related share.

Theresa Bean, (410) 786-2287 or James Hardesty, (410) 786-2629, for information regarding the regulatory impact analysis.

James Poyer, (410) 786-2261 or Jeffrey Buck, (410) 786-0407, for information regarding the inpatient psychiatric facility quality reporting program.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Availability of Certain Tables Exclusively Through the Internet on the CMS Website

Addendum A to this final rule summarizes the FY 2020 IPF PPS payment rates, outlier threshold, cost of living adjustment factors for Alaska and Hawaii, national and upper limit cost-to-charge ratios, and adjustment factors. In addition, the B Addenda to this final rule show the complete listing of ICD-10 Clinical Modification (CM) and Procedure Coding System codes underlying the Code First table (Addendum B-1), the FY 2020 IPF PPS comorbidity adjustment (Addenda B-2 and B-3), and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) procedure codes (Addendum B-4). The A and B addenda are available online at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/InpatientPsychFacilPPS/tools.html.

Tables setting forth the FY 2020 Wage Index for Urban Areas Based on Core-Based Statistical Area (CBSA) Labor Market Areas and the FY 2020 Wage Index Based on CBSA Labor Market Areas for Rural Areas are available exclusively through the internet, on the CMS website at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/IPFPPS/WageIndex.html. In addition, Addendum C to this final rule is a provider-level file of the effects of the change to the wage index methodology, and is available at the same CMS website address.

I. Executive Summary

A. Purpose

This final rule updates the prospective payment rates, the outlier threshold, and the wage index for Medicare inpatient hospital services provided by Inpatient Psychiatric Facilities (IPFs) for discharges occurring during the Fiscal Year (FY) beginning October 1, 2019 through September 30, 2020. Additionally, this final rule rebases and revises the IPF market basket to reflect a 2016 base year and uses the concurrent hospital wage data as the basis of the IPF wage index rather than using the prior year's Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) hospital wage data. Finally, this final rule updates the Inpatient Psychiatric Facility Quality Reporting (IPFQR) Program.

B. Summary of the Major Provisions

1. Inpatient Psychiatric Facilities Prospective Payment System (IPF PPS)

In this final rule we:

- Rebase and revise the IPF market basket to reflect a 2016 base year: Since the IPF PPS inception, the market basket used to update IPF PPS payments has been periodically rebased and revised to reflect more recent data on IPF cost structures. We last rebased and revised the market basket applicable to IPFs in the FY 2016 IPF PPS rule (80 FR 46656 through 46679), when we adopted a 2012-based IPF-specific market basket.

- Adjust the 2016-based IPF market basket update (2.9 percent) by a reduction for economy-wide productivity (0.4 percentage point) as required by section 1886(s)(2)(A)(i) of the Social Security Act (the Act). We further reduced the 2016-based IPF market basket update by 0.75 percentage point as required by section 1886(s)(2)(A)(ii) of the Act, resulting in an IPF payment rate update of 1.75 percent for FY 2020.

- Made technical rate setting changes: The IPF PPS payment rates are adjusted annually for inflation, as well as statutory and other policy factors. We updated:

++ The IPF PPS federal per diem base rate from $782.78 to $798.55.

++ The IPF PPS federal per diem base rate for providers who failed to report quality data to $782.85.

++ The Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) payment per treatment from $337.00 to $343.79.

++ The ECT payment per treatment for providers who failed to report quality data to $337.03.

++ The labor-related share from 74.8 percent to 76.9 percent.

++ The core-based statistical area (CBSA) rural and urban wage indices for FY 2020, using the FY 2020 pre-floor, pre-reclassified IPPS hospital wage index data and OMB designations from OMB Bulletin 17-01.

++ The wage index budget-neutrality factor to 1.0026.

++ The fixed dollar loss threshold amount from $12,865 to $14,960 to maintain estimated outlier payments at 2 percent of total estimated aggregate IPF PPS payments.

- Eliminate the 1-year lag in the wage index data: We aligned the IPF wage index data with the concurrent IPPS wage index data by removing the 1-year lag of the pre-floor, pre-reclassified IPPS hospital wage index upon which the IPF wage index is based.

2. Inpatient Psychiatric Facilities Quality Reporting (IPFQR) Program

We updated the IPFQR Program by adding a new measure for the program.

C. Summary of Impacts

| Provision description | Total transfers & cost reductions |

|---|---|

| FY 2020 IPF PPS payment update | The overall economic impact of this final rule is an estimated $65 million in increased payments to IPFs during FY 2020. |

| Updated quality reporting program (IPFQR) Program requirements | $0. |

II. Background

A. Overview of the Legislative Requirements of the IPF PPS

Section 124 of the Medicare, Medicaid, and State Children's Health Insurance Program Balanced Budget Refinement Act of 1999 (BBRA) (Pub. L. 106-113) required the establishment and implementation of an IPF PPS. Specifically, section 124 of the BBRA mandated that the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (the Secretary) develop a per diem PPS for inpatient hospital services furnished in psychiatric hospitals and excluded psychiatric units including an adequate patient classification system that reflects the differences in patient resource use and costs among psychiatric hospitals and excluded psychiatric units. “Excluded psychiatric unit” means a psychiatric unit in an IPPS hospital that is excluded from the IPPS, or a psychiatric unit in a Critical Access Hospital (CAH) that is excluded from the CAH payment system. These excluded psychiatric units would be paid under the IPF PPS.

Section 405(g)(2) of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA) (Pub. L. 108-173) extended the IPF PPS to psychiatric distinct part units of CAHs.

Sections 3401(f) and 10322 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Pub. L. 111-148) as amended by section 10319(e) of that Act and by section 1105(d) of the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 (Pub. L. 111-152) (hereafter referred to jointly as “the Affordable Care Act”) added subsection (s) to section 1886 of the Act.

Section 1886(s)(1) of the Act titled “Reference to Establishment and Implementation of System,” refers to section 124 of the BBRA, which relates to the establishment of the IPF PPS.

Section 1886(s)(2)(A)(i) of the Act requires the application of the productivity adjustment described in section 1886(b)(3)(B)(xi)(II) of the Act to the IPF PPS for the rate year (RY) beginning in 2012 (that is, a RY that coincides with a FY) and each subsequent RY. As noted in our FY 2019 IPF PPS final rule with comment period, published in the Federal Register on August 6, 2018 (83 FR 38576 through 38620), for the RY beginning in 2018, the productivity adjustment currently in place is equal to 0.8 percentage point.

Section 1886(s)(2)(A)(ii) of the Act requires the application of an “other adjustment” that reduces any update to an IPF PPS base rate by a percentage point amount specified in section 1886(s)(3) of the Act for the RY beginning in 2010 through the RY beginning in 2019. As noted in the FY 2019 IPF PPS final rule, for the RY beginning in 2018, section 1886(s)(3)(E) of the Act requires that the other adjustment reduction currently in place be equal to 0.75 percentage point.

Sections 1886(s)(4)(A)-(D) of the Act require that for RY 2014 and each subsequent RY, IPFs that fail to report required quality data with respect to such a RY will have their annual update to a standard federal rate for discharges reduced by 2.0 percentage points. This may result in an annual update being less than 0.0 for a RY, and may result in payment rates for the upcoming RY being less than such payment rates for the preceding RY. Any reduction for failure to report required quality data will apply only to the RY involved, and the Secretary will not take into account such reduction in computing the payment amount for a subsequent RY. (See section II.C of this final rule for an explanation of the IPF PPS RY.) More information about the specifics of the current IPFQR Program is available in the FY 2019 IFP PPS and Quality Reporting Updates for Fiscal Year Beginning October 1, 2018 final rule (83 FR 38589 through 38608).

To implement and periodically update these provisions, we have published various proposed and final rules and notices in the Federal Register. For more information regarding these documents, see the Center for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS) website at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/InpatientPsychFacilPPS/index.html?redirect=/InpatientPsychFacilPPS/.

B. Overview of the IPF PPS

The November 2004 IPF PPS final rule (69 FR 66922) established the IPF PPS, as required by section 124 of the BBRA and codified at 42 CFR part 412, subpart N. The November 2004 IPF PPS final rule set forth the federal per diem base rate for the implementation year (the 18-month period from January 1, 2005 through June 30, 2006), and provided payment for the inpatient operating and capital costs to IPFs for covered psychiatric services they furnish (that is, routine, ancillary, and capital costs, but not costs of approved educational activities, bad debts, and other services or items that are outside the scope of the IPF PPS). Covered psychiatric services include services for which benefits are provided under the fee-for-service Part A (Hospital Insurance Program) of the Medicare program.

The IPF PPS established the federal per diem base rate for each patient day in an IPF derived from the national average daily routine operating, ancillary, and capital costs in IPFs in FY 2002. The average per diem cost was updated to the midpoint of the first year under the IPF PPS, standardized to account for the overall positive effects of the IPF PPS payment adjustments, and adjusted for budget-neutrality.

The federal per diem payment under the IPF PPS is comprised of the federal per diem base rate described previously and certain patient- and facility-level payment adjustments for characteristics that were found in the regression analysis to be associated with statistically significant per diem cost differences, with statistical significance defined as p less than 0.05.

The patient-level adjustments include age, Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) assignment, and comorbidities; additionally, there are adjustments to reflect higher per diem costs at the beginning of a patient's IPF stay and lower costs for later days of the stay. Facility-level adjustments include adjustments for the IPF's wage index, rural location, teaching status, a cost-of-living adjustment for IPFs located in Alaska and Hawaii, and an adjustment for the presence of a qualifying emergency department (ED).

The IPF PPS provides additional payment policies for outlier cases, interrupted stays, and a per treatment payment for patients who undergo electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). During the IPF PPS mandatory 3-year transition period, stop-loss payments were also provided; however, since the transition ended as of January 1, 2008, these payments are no longer available.

A complete discussion of the regression analysis that established the IPF PPS adjustment factors can be found in the November 2004 IPF PPS final rule (69 FR 66933 through 66936).

C. Annual Requirements for Updating the IPF PPS

Section 124 of the BBRA did not specify an annual rate update strategy for the IPF PPS and was broadly written to give the Secretary discretion in establishing an update methodology. Therefore, in the November 2004 IPF PPS final rule, we implemented the IPF PPS using the following update strategy:

- Calculate the final federal per diem base rate to be budget-neutral for the 18-month period of January 1, 2005 through June 30, 2006.

- Use a July 1 through June 30 annual update cycle.

- Allow the IPF PPS first update to be effective for discharges on or after July 1, 2006 through June 30, 2007.

In RY 2012, we proposed and finalized switching the IPF PPS payment rate update from a RY that begins on July 1 and ends on June 30, to one that coincides with the federal FY that begins October 1 and ends on September 30. In order to transition from one timeframe to another, the RY 2012 IPF PPS covered a 15-month period from July 1, 2011 through September 30, 2012. Therefore, the IPF RY has been equivalent to the October 1 through September 30 federal FY since RY 2013. For further discussion of the 15-month market basket update for RY 2012 and changing the payment rate update period to coincide with a FY period, we refer readers to the RY 2012 IPF PPS proposed rule (76 FR 4998) and the RY 2012 IPF PPS final rule (76 FR 26432).

In November 2004, we implemented the IPF PPS in a final rule that published on November 15, 2004 in the Federal Register (69 FR 66922). In developing the IPF PPS, and to ensure that the IPF PPS is able to account adequately for each IPF's case-mix, we performed an extensive regression analysis of the relationship between the per diem costs and certain patient and facility characteristics to determine those characteristics associated with statistically significant cost differences on a per diem basis. That regression analysis is described in detail in our November 28, 2003 IPF proposed rule (68 FR 66923; 66928 through 66933) and our November 15, 2004 IPF final rule (69 FR 66933 through 66960). For characteristics with statistically significant cost differences, we used the regression coefficients of those variables to determine the size of the corresponding payment adjustments.

In that final rule, we explained the reasons for delaying an update to the adjustment factors, derived from the regression analysis, including waiting until we have IPF PPS data that yields as much information as possible regarding the patient-level characteristics of the population that each IPF serves. We indicated that we did not intend to update the regression analysis and the patient-level and facility-level adjustments until we complete that analysis. Until that analysis is complete, we stated our intention to publish a notice in the Federal Register each spring to update the IPF PPS (69 FR 66966).

On May 6, 2011, we published a final rule in the Federal Register titled, “Inpatient Psychiatric Facilities Prospective Payment System—Update for Rate Year Beginning July 1, 2011 (RY 2012)” (76 FR 26432), which changed the payment rate update period to a RY that coincides with a FY update. Therefore, final rules are now published in the Federal Register in the summer to be effective on October 1. When proposing changes in IPF payment policy, a proposed rule would be issued in the spring, and the final rule in the summer to be effective on October 1. For a detailed list of updates to the IPF PPS, we refer readers to our regulations at 412.428.

The most recent IPF PPS annual update was published in a final rule on August 6, 2018 in the Federal Register titled, “Medicare Program; FY 2019 Inpatient Psychiatric Facilities Prospective Payment System and Quality Reporting Updates” (83 FR 38576), which updated the IPF PPS payment rates for FY 2019. That final rule updated the IPF PPS federal per diem base rates that were published in the FY 2018 IPF PPS Rate Update final rule (82 FR 36771) in accordance with our established policies.

III. Provisions of the FY 2020 IPF PPS Final Rule and Responses to Comments

On April 23, 2019 we published the FY 2020 IPF PPS proposed rule (84 FR 16948). We received 24 comments on the FY 2020 IPF PPS proposed rule, with some commenters addressing multiple issues. We received 4 comments on payment policy issues, 19 comments on quality issues, and 6 comments that were outside of the scope of the proposed rule.

A. Rebasing and Revising of the Market Basket for the IPF PPS

1. Background

Originally, the input price index used to develop the IPF PPS was the Excluded Hospital with Capital market basket. This market basket was based on 1997 Medicare cost reports for Medicare-participating inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), IPFs, long-term care hospitals (LTCHs), cancer hospitals, and children's hospitals. Although “market basket” technically describes the mix of goods and services used in providing health care at a given point in time, this term is also commonly used to denote the input price index (that is, cost category weights and price proxies) derived from that market basket. Accordingly, the term “market basket,” as used in this document, refers to an input price index.

Since the IPF PPS inception, the market basket used to update IPF PPS payments has been rebased and revised to reflect more recent data on IPF cost structures. We last rebased and revised the market basket applicable to the IPF PPS in the FY 2016 IPF PPS final rule (80 FR 46656 through 46679), where we adopted a 2012-based IPF market basket. The 2012-based IPF market basket used Medicare cost report data for both Medicare-participating freestanding psychiatric hospitals and hospital-based psychiatric units. References to the historical market baskets used to update IPF PPS payments are listed in the FY 2016 IPF PPS final rule (80 FR 46656). For the FY 2020 IPF PPS proposed rule, we proposed to rebase and revise the IPF market basket to reflect a 2016 base year.

2. Overview of the 2016-Based IPF Market Basket

The proposed 2016-based IPF market basket is a fixed-weight, Laspeyres-type price index. A Laspeyres price index measures the change in price, over time, of the same mix of goods and services purchased in the base period. Any changes in the quantity or mix of goods and services (that is, intensity) purchased over time relative to a base period are not measured.

The index itself is constructed in three steps. First, a base period is selected (for the proposed IPF market basket, the base period is 2016) and total base period expenditures are estimated for a set of mutually exclusive and exhaustive spending categories. Each category is calculated as a proportion of total costs. These proportions are called cost or expenditure weights. Second, each expenditure category is matched to an appropriate price or wage variable, referred to as a price proxy. In nearly every instance, these price proxies are derived from publicly available statistical series that are published on a consistent schedule (preferably at least on a quarterly basis). Finally, the expenditure weight for each cost category is multiplied by the level of its respective price proxy. The sum of these products (that is, the expenditure weights multiplied by their price levels) for all cost categories yields the composite index level of the market basket in a given period. Repeating this step for other periods produces a series of market basket levels over time. Dividing an index level for a given period by an index level for an earlier period produces a rate of growth in the input price index over that timeframe.

As noted, the market basket is described as a fixed-weight index because it represents the change in price over time of a constant mix (quantity and intensity) of goods and services needed to furnish IPF services. The effects on total expenditures resulting from changes in the mix of goods and services purchased after the base period are not measured. For example, an IPF hiring more nurses after the base period to accommodate the needs of patients will increase the volume of goods and services purchased by the IPF, but would not be factored into the price change measured by a fixed-weight IPF market basket. Only when the index is rebased will changes in the quantity and intensity be captured, with those changes being reflected in the cost weights. Therefore, we rebase the market basket periodically so that the cost weights reflect recent changes in the mix of goods and services that IPFs purchase to furnish inpatient care between base periods.

3. Creating an IPF-Specific Market Basket

As discussed in the FY 2016 final rule (80 FR 46656 through 46679), the 2012-based IPF market basket reflects the Medicare cost reports for both freestanding and hospital-based facilities. Previous market baskets, such as the 2008-based rehabilitation, psychiatric, and long-term care (RPL) market basket, were calculated using Medicare cost report data for freestanding facilities only. We used only freestanding facilities due to concerns regarding our ability to incorporate Medicare cost report data for hospital-based providers. After research on the available Medicare cost report data, we concluded that Medicare cost report data for both freestanding IPFs and hospital-based IPFs can be used to calculate the major market basket cost weights for a stand-alone IPF market basket. In the FY 2016 IPF PPS final rule (80 FR 46656 through 46679), we finalized a detailed methodology to derive market basket cost weights using Medicare cost report data for both freestanding IPFs and hospital-based IPFs.

For the FY 2020 proposed rule, we proposed to rebase and revise the 2012-based IPF market basket to a 2016 base year reflecting both freestanding IPFs and hospital-based IPFs. In section III.A.3.a., “Development of Cost Categories and Weights,” we provide a detailed description of our proposed methodology used to develop the 2016-based IPF market basket.

a. Development of Cost Categories and Weights

i. Medicare Cost Reports

We proposed a 2016-based IPF market basket that consists of seven major cost categories and a residual derived from the 2016 Medicare cost reports (CMS Form 2552-10 effective for cost reports beginning on or after May 1, 2010) for freestanding and hospital-based IPFs. CMS Form 2552-10 was also used to derive the major cost categories in the 2012-based IPF market basket. The seven cost categories are Wages and Salaries, Employee Benefits, Contract Labor, Pharmaceuticals, Professional Liability Insurance (PLI), Home Office Contract Labor, and Capital. The 2012-based IPF market basket did not have a Home Office Contract Labor cost category. The residual “All Other” category reflects all remaining costs not captured in the seven cost categories. The 2016 cost reports include providers whose cost reporting period beginning date is on or between October 1, 2015 and September 30, 2016. We proposed to select 2016 as the base year because we believe that the Medicare cost reports for this year represent the most recent, complete set of Medicare cost report data available at the time of rulemaking.

Similar to the Medicare cost report data used to develop the 2012-based IPF market basket, the Medicare cost report data for 2016 show large differences between some providers' Medicare length of stay (LOS) and total facility LOS. Our goal has always been to measure cost weights that are reflective of case mix and practice patterns associated with providing services to Medicare beneficiaries. Therefore, we proposed to limit our selection of Medicare cost reports used in the 2016-based IPF market basket to those facilities that had a Medicare LOS within a comparable range of their total facility average LOS. The Medicare average LOS for freestanding IPFs is calculated from data reported on line 14 of Worksheet S-3, part I. The Medicare average LOS for hospital-based IPFs is calculated from data reported on line 16 of Worksheet S-3, part I. To derive the proposed 2016-based IPF market basket, for those IPFs with an average facility LOS of greater than or equal to 15 days, we proposed to include IPFs where the Medicare LOS is within 50 percent (higher or lower) of the average facility LOS. For those IPFs whose average facility LOS is less than 15 days, we proposed to include IPFs where the Medicare LOS is within 95 percent (higher or lower) of the facility LOS. We proposed to apply this LOS edit to the data for IPFs to exclude providers that serve a population whose LOS would indicate that the patients served are not consistent with a LOS of a typical Medicare patient. This is the same LOS edit applied to the 2012-based IPF market basket.

Applying these trims to the approximate 1,600 total cost reports (freestanding and hospital-based) resulted in roughly 1,500 IPF Medicare cost reports with an average Medicare LOS of 12 days, average facility LOS of 9 days, and Medicare utilization (as measured by Medicare inpatient IPF days as a percentage of total facility days) of 26 percent. Providers excluded from the proposed 2016-based IPF market basket (about 130 Medicare cost reports) had an average Medicare LOS of 25 days, average facility LOS of 55 days, and a Medicare utilization of 4 percent. Of those excluded, about 70 percent of these were freestanding providers; on the other hand, freestanding providers represent about 30 percent of all IPFs. We note that seventy percent of those excluded from the 2012-based IPF market basket using this LOS edit were also freestanding providers.

Using the post-LOS set of 2016 Medicare cost reports, we calculated costs for the seven major cost categories (Wages and Salaries, Employee Benefits, Contract Labor, Professional Liability Insurance, Pharmaceuticals, Home Office Contract Labor, and Capital). For comparison, the 2012-based IPF market basket utilized the Bureau of Economic Analysis Benchmark Input-Output data to derive the Home Office Contract Labor cost weight rather than the Medicare cost report data. A more detailed discussion of this methodological change is provided.

Similar to the 2012-based IPF market basket major cost weights, the proposed 2016-based IPF market basket cost weights reflect Medicare allowable costs (routine, ancillary, and capital costs) that are eligible for inclusion under the IPF PPS payments. We proposed to define Medicare allowable costs for freestanding IPFs as Worksheet B, part I, column 26, lines 30 through 35, 50 through 76 (excluding 52 and 75), 90 through 91, and 93. For hospital-based IPFs, we proposed that total Medicare allowable costs be equal to total costs for the IPF inpatient unit after the allocation of overhead costs (Worksheet B, part I, column 26, line 40) and a portion of total ancillary costs (Worksheet B, part I, column 26, lines 50 through 76 (excluding 52 and 75), 90 through 91, and 93). We proposed to calculate the portion of ancillary costs attributable to the hospital-based IPF for a given ancillary cost center by multiplying total facility ancillary costs for the specific cost center (as reported on Worksheet B, part I, column 26) by the ratio of IPF Medicare ancillary costs for the cost center (as reported on Worksheet D-3, column 3 for IPF subproviders) to total Medicare ancillary costs for the cost center (equal to the sum of Worksheet D-3, column 3 for all Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS), Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF), IRF, and IPF). This is the same methodology used for the 2012-based IPF market basket.

We provide a description of the proposed methodologies used to derive costs for the seven major cost categories.

Wages and Salaries Costs

For freestanding IPFs, we proposed that Wages and Salaries costs be derived as the sum of routine inpatient salaries, ancillary salaries, and a proportion of overhead (or general service cost centers in the MCR) salaries as reported on Worksheet A, column 1. Since overhead salary costs are attributable to the entire IPF, we only include the proportion attributable to the Medicare allowable cost centers. We proposed to estimate the proportion of overhead salaries that are attributed to Medicare allowable costs centers by multiplying the ratio of Medicare allowable salaries (Worksheet A, column 1, lines 50 through 76 (excluding 52 and 75), 90 through 91, and 93) to total salaries (Worksheet A, column 1, line 200) times total overhead salaries (Worksheet A, column 1, lines 4 through 18). This is the same methodology used in the 2012-based IPF market basket.

We proposed that Wages and Salaries costs for hospital-based IPFs are derived by summing inpatient routine salary costs, ancillary salaries, overhead salary costs attributable to the IPF inpatient unit, and a portion of overhead salary costs attributable to the ancillary departments.

We proposed to calculate hospital-based inpatient routine salary costs using Worksheet A, column 1, line 40.

We proposed to calculate hospital-based ancillary salary costs for a specific cost center (Worksheet A, column 1, lines 50 through 76 (excluding 52 and 75), 90 through 91, and 93) using salary costs from Worksheet A, column 1 multiplied by the ratio of IPF Medicare ancillary costs for the cost center (as reported on Worksheet D-3, column 3 for IPF subproviders) to total Medicare ancillary costs for the cost center (equal to the sum of Worksheet D-3, column 3 for IPPS, SNF, IRF, and IPF).

We proposed to calculate the hospital-based overhead salaries attributable to the IPF inpatient unit by first calculating total noncapital overhead costs (Worksheet B, part I, columns 4-18, line 40 less Worksheet B, part II, columns 4-18) for each ancillary department. We then multiplied total noncapital overhead costs by the ratio of total facility overhead salaries (as reported on Worksheet A, column 1, lines 4-18) to total facility noncapital overhead costs (as reported on Worksheet A, column 1 and 2, lines 4-18).

We proposed to calculate the hospital-based portion of overhead salaries attributable to each ancillary department by first calculating total noncapital overhead costs attributable to each specific ancillary department (Worksheet B, part I, columns 4-18 less Worksheet B, part II, columns 4-18). We then identified the portion of these noncapital overhead costs attributable to Wages and Salaries by multiplying these costs by the ratio of total facility overhead salaries (as reported on Worksheet A, column 1, lines 4-18) to total overhead costs (as reported on Worksheet A, column 1 & 2, lines 4-18). Finally, we identified the portion of these overhead salaries for each ancillary department that is attributable to the hospital-based IPF by multiplying by the ratio of IPF Medicare ancillary costs for the cost center (as reported on Worksheet D-3, column 3 for hospital-based IPFs) to total Medicare ancillary costs for the cost center (equal to the sum of Worksheet D-3, column 3 for all IPPS, SNF, IRF, and IPF).

This is the same Wages and Salaries Costs methodology used to derive the 2012-based IPF market basket.

Employee Benefits Costs

Effective with the implementation of CMS Form 2552-10, we began collecting Employee Benefits and Contract Labor data on Worksheet S-3, part V.

For 2016 Medicare cost report data, the majority of providers did not report data on Worksheet S-3, part V. One (1) percent of freestanding IPFs and roughly 40 percent of hospital-based IPFs reported data on Worksheet S-3, part V. Again, we continue to encourage all providers to report these data on the Medicare cost report.

For freestanding IPFs, we proposed Employee Benefits costs were equal to the data reported on Worksheet S-3, part V, column 2, line 2. We note that while not required to do so, freestanding IPFs also may report Employee Benefits data on Worksheet S-3, part II, which is applicable to only IPPS providers. For those freestanding IPFs that reported Worksheet S-3, part II data, but not Worksheet S-3, part V, we proposed to use the sum of Worksheet S-3, part II lines 17, 18, 20, and 22 to derive Employee Benefits costs. This proposed method allowed us to obtain data from more than 20 freestanding IPFs (roughly 5 percent of all freestanding IPFs) than if we were to only use Worksheet S-3, part V data as done for the 2012-based IPF market basket.

For hospital-based IPFs, we proposed to calculate total benefit costs as the sum of inpatient unit benefit costs, a portion of ancillary benefits, and a portion of overhead benefits attributable to the routine inpatient unit and a portion of overhead benefits attributable to the ancillary departments.

We proposed hospital-based inpatient unit benefit costs be equal to Worksheet S-3 part V, column 2, line 3.

We proposed the hospital-based portion of ancillary benefit costs be equal to hospital-based ancillary salaries times the ratio of total facility benefits to total facility salaries.

We proposed that the hospital-based portion of overhead benefits attributable to the routine inpatient unit and ancillary departments be calculated by multiplying ancillary salaries for the hospital-based IPF and overhead salaries attributable to the hospital-based IPF (determined in the derivation of hospital-based IPF Wages and Salaries costs as described) by the ratio of total facility benefits to total facility salaries. Total facility benefits is equal to the sum of Worksheet S-3, part II, column 4, lines 17-25 and total facility salaries is equal to Worksheet S-3, part II, column 4, line 1.

Contract Labor Costs

Contract Labor costs are primarily associated with direct patient care services. Contract Labor costs are exclusive of Home Office Contract Labor costs. Contract labor costs for other services such as accounting, billing, and legal are calculated separately using other government data sources as described in section III.A.3.a.iii of this final rule. To derive contract labor costs using Worksheet S-3, part V data, for freestanding IPFs, we proposed Contract Labor costs be equal to Worksheet S-3, part V, column 1, line 2. As we noted for Employee Benefits, freestanding IPFs also may report Contract Labor data on Worksheet S-3, part II, which is applicable to only IPPS providers. For those freestanding IPFs that reported Worksheet S-3, part II data, but not Worksheet S-3, part V, we proposed to use the sum of Worksheet S-3, part II lines 11 and 13 to derive Contract Labor costs. For the 2012-based IPF market basket, we only used data from Worksheet S-3, part V, column 1, line 2 to derive the Contract Labor costs for freestanding IPFs.

For hospital-based IPFs, we proposed that Contract Labor costs be equal to Worksheet S-3, part V, column 1, line 3. Reporting of this data continues to be somewhat limited; therefore, we continue to encourage all providers to report these data on the Medicare cost report.

Pharmaceuticals Costs

For freestanding IPFs, we proposed to calculate pharmaceuticals costs using non-salary costs reported on Worksheet A, column 7 less Worksheet A, column 1 for the pharmacy cost center (line 15) and drugs charged to patients cost center (line 73).

For hospital-based IPFs, we proposed to calculate pharmaceuticals costs as the sum of a portion of the non-salary pharmacy costs and a portion of the non-salary drugs charged to patient costs reported for the total facility.

We proposed that hospital-based non-salary pharmacy costs attributable to the hospital-based IPF are calculated by multiplying total pharmacy costs attributable to the hospital-based IPF (as reported on Worksheet B, part I, column 15, line 40) by the ratio of total non-salary pharmacy costs (Worksheet A, column 2, line 15) to total pharmacy costs (sum of Worksheet A, column 1 and 2 for line 15) for the total facility.

We proposed that hospital-based non-salary drugs charged to patient costs attributable to the hospital-based IPF are calculated by multiplying total non-salary drugs charged to patient costs (Worksheet B, part I, column 0, line 73 plus Worksheet B, part I, column 15, line 73 less Worksheet A, column 1, line 73) for the total facility by the ratio of Medicare drugs charged to patient ancillary costs for the IPF unit (as reported on Worksheet D-3 for IPF subproviders, column 3, line 73) to total Medicare drugs charged to patients ancillary costs for the total facility (equal to the sum of Worksheet D-3, column 3, line 73, for all IPPS, SNF, IRF, and IPF).

This is the same Pharmaceuticals Costs methodology used to derive the 2012-based IPF market basket.

Professional Liability Insurance (PLI) Costs

For freestanding IPFs, we proposed that PLI costs (often referred to as malpractice costs) are equal to premiums, paid losses and self-insurance costs reported on Worksheet S-2, part I, columns 1 through 3, line 118.

For hospital-based IPFs, we proposed to assume that the PLI weight for the total facility is similar to the hospital-based IPF unit since the only data reported on this worksheet is for the entire facility. Therefore, hospital-based IPF PLI costs were equal to total facility PLI (as reported on Worksheet S-2, part I, columns 1 through 3, line 118) divided by total facility costs (as reported on Worksheet A, columns 1 and 2, line 200) times hospital-based IPF Medicare allowable total costs. Our assumption is that the same proportion of expenses are used among each unit of the hospital.

This is the same methodology used to derive the 2012-based IPF market basket.

Home Office/Related Organization Contract Labor Costs

For the 2016-based IPF market basket, we proposed to determine the home office/related organization contract labor costs using Medicare cost report data. This is a different methodology compared to the 2012-based IPF market basket. We believe this proposed methodology is an improvement as it is based on the data directly submitted by providers on the Medicare cost report. It is also consistent with the methodology we adopted when we rebased and revised the 2014-based IPPS market basket (52 FR 38159).

For hospital-based IPFs, we proposed to calculate the home office contract labor cost weight using data reported on Worksheet S-3, part II, column 4, lines 14, 1401, 1402, 2550, and 2551 and total facility costs (Worksheet B, part 1, column 26, line 202). We proposed to use total facility costs as the denominator for calculating the home office contract labor cost weight as these expenses reported on Worksheet S-3, part II reflect the entire hospital facility. Our assumption is that the same proportion of expenses are used among each unit of the hospital. Similar to the other market basket costs weights, we proposed to trim the Home Office Contract Labor cost weight to remove outliers. Since not all hospital-based IPFs will have home office contract labor costs, we proposed to trim the top one percent of the Home Office Contract Labor cost weight. This is the same trimming methodology used to calculate the Home Office Contract Labor cost weight in the 2016-based IPPS market basket. Using this proposed methodology, we calculate a Home Office Contract Labor cost weight for hospital-based IPFs of 3.7 percent. We discuss the trimming methodology for the other major cost categories in the “Final Major Cost Category Computation” in section ii. of this final rule.

Freestanding IPFs are not required to complete Worksheet S-3, part II. Therefore, to estimate the Home Office Contract Labor cost weight, we proposed the following methodology:

(1) Using hospital-based IPFs with a home office and also passing the one percent trim as described, we calculate the ratio of the Home Office Contract Labor cost weight to the Medicare allowable nonsalary, noncapital cost weight (Medicare allowable nonsalary, noncapital costs as a percent of total Medicare allowable costs).

(2) We identify freestanding IPFs that report a home office on Worksheet S-2, part I, line 140—roughly 85 percent. We proposed to calculate a Home Office Contract Labor cost weight for these freestanding IPFs by multiplying the ratio calculated in Step (1) by the Medicare allowable nonsalary, noncapital cost weight for those freestanding IPFs with a home office.

(3) We then calculated the freestanding IPF cost weight by multiplying the Home Office Contract Labor cost weight in step (2) by the total Medicare allowable costs for IPFs with a home office as a percent of total Medicare allowable costs for all freestanding IPFs.

To calculate the Home Office Contract Labor cost weight, we proposed to weight together the freestanding Home Office Contract Labor cost weight (3.0 percent) and the hospital-based Home Office Contract Labor cost weight (3.7 percent) using total Medicare allowable costs. The resulting overall cost weight for Home Office was 3.5 percent (3.0 percent × 37 percent + 3.7 percent × 63 percent).

For the 2012-based IPF market basket, we calculated the Home Office Contract Labor cost weight using the Bureau of Economic Analysis Input-Output expense data for North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code 55, Management of Companies and Enterprises using the methodology described in section III.A.3.a.iii (Derivation of the Detailed Operating Cost Weights) of this final rule.

Capital Costs

For freestanding IPFs, we proposed capital costs to be equal to Medicare allowable capital costs as reported on Worksheet B, part II, column 26, lines 30 through 35, 50 through 76 (excluding 52 and 75), 90 through 91, and 93. This is the same methodology used for the 2012-based IPF market basket.

For hospital-based IPFs, we proposed capital costs to be equal to IPF inpatient capital costs (as reported on Worksheet B, part II, column 26, line 40) and a portion of IPF ancillary capital costs. We calculated the portion of ancillary capital costs attributable to the hospital-based IPF for a given cost center by multiplying total facility ancillary capital costs for the specific ancillary cost center (as reported on Worksheet B, part II, column 26) by the ratio of IPF Medicare ancillary costs for the cost center (as reported on Worksheet D-3, column 3 for IPF subproviders) to total Medicare ancillary costs for the cost center (equal to the sum of Worksheet D-3, column 3 for all IPPS, SNF, IRF, and IPF). This is the same methodology used for the 2012-based IPF market basket.

ii. Final Major Cost Category Computation

After we derived costs for the seven major cost categories for each provider using the Medicare cost report data as described, we proposed to trim the data for outliers. The proposed trimming methodology for the Home Office Contract Labor cost weight is slightly different than the proposed trimming methodology for the other six cost categories. For the Wages and Salaries, Employee Benefits, Contract Labor, Pharmaceuticals, Professional Liability Insurance, and Capital cost weights, we first divided the costs for each of these six categories by total Medicare allowable costs calculated for the provider to obtain cost weights for the universe of IPF providers. Next, we applied a mutually exclusive top and bottom 5 percent trim for each cost weight to remove outliers. After the outliers have been removed, we summed the costs for each category across all remaining providers. We then divided this by the sum of total Medicare allowable costs across all remaining providers to obtain a cost weight for the proposed 2016-based IPF market basket for the given category.

Finally, we calculated the residual “All Other” cost weight that reflects all remaining costs that are not captured in the seven cost categories listed. We did not receive any comments on the derivation of the major cost weights. In this final rule, we are finalizing our methodology for deriving the major cost weights as we proposed.

Table 1 presents the major cost categories and weights calculated from the Medicare cost reports for the 2016-based IPF market basket as well as for the 2012-based IPF market basket.

| Major cost categories | Final 2016- based IPF market basket (percent) | 2012-based IPF market basket (percent) |

|---|---|---|

| Wages and Salaries | 51.2 | 51.0 |

| Employee Benefits | 13.5 | 13.1 |

| Contract Labor | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Professional Liability Insurance (Malpractice) | 0.9 | 1.1 |

| Pharmaceuticals | 4.7 | 4.8 |

| Home Office/Related Organization Contract Labor | 3.5 | n/a |

| Capital | 7.1 | 7.0 |

| “All Other” Residual | 17.9 | 21.6 |

| Note: Total may not sum to 100 due to rounding. | ||

As we did for the 2012-based IPF market basket, we proposed to allocate the Contract Labor cost weight to the Wages and Salaries and Employee Benefits cost weights based on their relative proportions under the assumption that contract labor costs are comprised of both wages and salaries and employee benefits. The Contract Labor allocation proportion for Wages and Salaries is equal to the Wages and Salaries cost weight as a percent of the sum of the Wages and Salaries cost weight and the Employee Benefits cost weight. For the proposed rule, this rounded percentage was 79 percent; therefore, we proposed to allocate 79 percent of the Contract Labor cost weight to the Wages and Salaries cost weight and 21 percent to the Employee Benefits cost weight. The 2012-based IPF market basket percentage was 80 percent. We did not receive any comments on the allocation of the Contract Labor cost weight.

Table 2 shows the Wages and Salaries and Employee Benefit cost weights after Contract Labor cost weight allocation for both the 2016-based IPF market basket and 2012-based IPF market basket.

| Major cost categories | Final 2016- based IPF market basket | 2012-Based IPF market basket |

|---|---|---|

| Wages and Salaries | 52.2 | 52.1 |

| Employee Benefits | 13.8 | 13.4 |

iii. Derivation of the Detailed Operating Cost Weights

To further divide the “All Other” residual cost weight estimated from the 2016 Medicare Cost Report data into more detailed cost categories, we proposed to use the 2012 Benchmark Input-Output (I-O) “Use Tables/Before Redefinitions/Purchaser Value” for NAICS 622000 Hospitals, published by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). These data, publicly available at http://www.bea.gov/industry/io_annual.htm, are the most recent data available at the time of rulemaking. For the 2012-based IPF market basket, we used the 2007 Benchmark I-O data.

The BEA Benchmark I-O data are scheduled for publication every five years. The 2012 Benchmark I-O data are derived from the 2012 Economic Census and are the building blocks for BEA's economic accounts. They represent the most comprehensive and complete set of data on the economic processes or mechanisms by which output is produced and distributed.[1] BEA also produces Annual I-O estimates; however, while based on a similar methodology, these estimates reflect less comprehensive and less detailed data sources and are subject to revision when benchmark data becomes available. Instead of using the less detailed Annual I-O data, we proposed to inflate the 2012 Benchmark I-O data forward to 2016 by applying the annual price changes from the respective price proxies to the appropriate market basket cost categories obtained from the 2012 Benchmark I-O data. We then proposed to calculate the cost shares that each cost category represents of the inflated 2016 data. These resulting 2016 cost shares were applied to the “All Other” residual cost weight to obtain the proposed detailed cost weights for the 2016-based IPF market basket. For example, the cost for Food: Direct Purchases represents 5.0 percent of the sum of the “All Other” 2016 Benchmark I-O Hospital Expenditures inflated to 2016. Therefore, the Food: Direct Purchases cost weight represents 5.0 percent of the 2016-based IPF market basket's “All Other” cost category (17.9 percent), yielding a “final” Food: Direct Purchases cost weight of 0.9 percent in the proposed 2016-based IPF market basket (0.05 * 17.9 percent = 0.9 percent).

Using this methodology, we proposed to derive seventeen detailed IPF market basket cost category weights from the proposed 2016-based IPF market basket residual cost weight (17.9 percent). These categories were: (1) Electricity, (2) Fuel, Oil, and Gasoline, (3) Food: Direct Purchases, (4) Food: Contract Services, (5) Chemicals, (6) Medical Instruments, (7) Rubber & Plastics, (8) Paper and Printing Products, (9) Miscellaneous Products, (10) Professional Fees: Labor-related, (11) Administrative and Facilities Support Services, (12) Installation, Maintenance, and Repair, (13) All Other Labor-related Services, (14) Professional Fees: Nonlabor-related, (15) Financial Services, (16) Telephone Services, and (17) All Other Nonlabor-related Services. We note that for the 2012-based IPF market basket, we had a Water and Sewerage cost weight. For the proposed 2016-based IPF market basket, we proposed to include Water and Sewerage in the Electricity cost weight due to the small amount of costs in this category.

We did not receive any comments on the derivation of the detailed operating cost weights. In this final rule, we are finalizing our methodology for deriving the detailed operating cost weights as we proposed.

iv. Derivation of the Detailed Capital Cost Weights

As described in section III.A.3.a.i. of this final rule, we proposed a Capital-Related cost weight of 7.1 percent as obtained from the 2016 Medicare cost reports for freestanding and hospital-based IPF providers. We proposed to further separate this total Capital-Related cost weight into more detailed cost categories. Using 2016 Medicare cost reports, we were able to group Capital-Related costs into the following categories: Depreciation, Interest, Lease, and Other Capital-Related costs. For each of these categories, we proposed to determine separately for hospital-based IPFs and freestanding IPFs what proportion of total capital-related costs the category represent.

For freestanding IPFs, we proposed to derive the proportions for Depreciation, Interest, Lease, and Other Capital-related costs using the data reported by the IPF on Worksheet A-7, which is the same methodology used for the 2012-based IPF market basket.

For hospital-based IPFs, data for these four categories were not reported separately for the subprovider; therefore, we proposed to derive these proportions using data reported on Worksheet A-7 for the total facility. We are assuming the cost shares for the overall hospital are representative for the hospital-based subprovider IPF unit. For example, if depreciation costs make up 60 percent of total capital costs for the entire facility, we believe it was reasonable to assume that the hospital-based IPF will also have a 60 percent proportion because it is a subprovider unit contained within the total facility. This is the same methodology used for the 2012-based IPF market basket.

In order to combine each detailed capital cost weight for freestanding and hospital-based IPFs into a single capital cost weight for the 2016-based IPF market basket, we proposed to weight together the shares for each of the categories (Depreciation, Interest, Lease, and Other Capital-related costs) based on the share of total capital costs each provider type represents of the total capital costs for all IPFs for 2016. Applying this methodology results in proportions of total capital-related costs for Depreciation, Interest, Lease and Other Capital-related costs that are representative of the universe of IPF providers. This is the same methodology used for the 2012-based IPF market basket.

Next, we proposed to allocate lease costs across each of the remaining detailed capital-related cost categories as done in the 2012-based IPF market basket. This resulted in three primary capital-related cost categories in the 2016-based IPF market basket: Depreciation, Interest, and Other Capital-Related costs. As done in the 2012-based IPF market basket, lease costs are unique in that they are not broken out as a separate cost category in the 2016-based IPF market basket, but rather we proposed to proportionally distribute these costs among the cost categories of Depreciation, Interest, and Other Capital-Related, reflecting the assumption that the underlying cost structure of leases is similar to that of capital-related costs in general. As done under the 2012-based IPF market basket, we proposed to assume that 10 percent of the lease costs as a proportion of total capital-related costs represents overhead and assign those costs to the Other Capital-Related cost category accordingly. We proposed to distribute the remaining lease costs proportionally across the three cost categories (Depreciation, Interest, and Other Capital-Related) based on the proportion that these categories comprise of the sum of the Depreciation, Interest, and Other Capital-related cost categories (excluding lease expenses). This is the same methodology used for the 2012-based IPF market basket. The allocation of these lease expenses are shown in Table 3.

Finally, we proposed to further divide the Depreciation and Interest cost categories. We proposed to separate Depreciation into the following two categories: (1) Building and Fixed Equipment; and (2) Movable Equipment; and proposed to separate Interest into the following two categories: (1) Government/Nonprofit; and (2) For-profit.

To disaggregate the Depreciation cost weight, we determined the percent of total Depreciation costs for IPFs that is attributable to Building and Fixed Equipment, which we hereafter refer to as the “fixed percentage.” For the 2016-based IPF market basket, we proposed to use slightly different methods to obtain the fixed percentages for hospital-based IPFs compared to freestanding IPFs.

For freestanding IPFs, we proposed to use depreciation data from Worksheet A-7 of the 2016 Medicare cost reports. However, for hospital-based IPFs, we determined that the fixed percentage for the entire facility may not be representative of the IPF subprovider unit due to the entire facility likely employing more sophisticated movable assets that are not utilized by the hospital-based IPF. Therefore, for hospital-based IPFs, we proposed to calculate a fixed percentage using: (1) Building and fixture capital costs allocated to the subprovider unit as reported on Worksheet B, part I line 40; and (2) building and fixture capital costs for the top five ancillary cost centers utilized by hospital-based IPFs. We proposed to then weight these two fixed percentages (inpatient and ancillary) using the proportion that each capital cost type represents of total capital costs in the proposed 2016-based IPF market basket. We then proposed to weight the fixed percentages for hospital-based and freestanding IPFs together using the proportion of total capital costs each provider type represents. For both freestanding and hospital-based IPFs, this is the same methodology used for the 2012-based IPF market basket.

To disaggregate the Interest cost weight, we determined the percent of total interest costs for IPFs that were attributable to government and nonprofit facilities, the “nonprofit percentage.” For the 2016-based IPF market basket, we proposed to use interest costs data from Worksheet A-7 for both freestanding and hospital-based IPFs. We then determined the percent of total interest costs that are attributed to government and nonprofit IPFs separately for hospital-based and freestanding IPFs and weight the nonprofit percentages for hospital-based and freestanding IPFs together using the proportion of total capital costs each provider type represents. This is the same methodology used for the 2012-based IPF market basket.

We did not receive public comments on the derivation of the detailed capital cost weights. In this final rule, we are finalizing our methodology for deriving the detailed capital cost weights as we proposed. Table 3 provides the detailed capital cost share composition of the 2016-based IPF market basket. These detailed capital cost share composition percentages are applied to the total Capital-Related cost weight of 7.1 percent determined in section III.A.3.a.i. of this final rule.

| Capital cost share composition before lease expense allocation (percent) | Capital cost share composition after lease expense allocation (percent) | |

|---|---|---|

| Depreciation | 60 | 74 |

| Building and Fixed Equipment | 43 | 52 |

| Movable Equipment | 18 | 22 |

| Interest | 13 | 16 |

| Government/Nonprofit | 10 | 12 |

| For Profit | 3 | 4 |

| Lease | 20 | n/a |

| Other | 7 | 10 |

| Note: Detail may not add to total due to rounding. | ||

v. 2016-Based IPF Market Basket Cost Categories and Weights

Table 4 shows the cost categories and weights for the final 2016-based IPF market basket and the 2012-based IPF market basket.

b. Selection of Price Proxies

After developing the cost weights for the proposed 2016-based IPF market basket, we selected the most appropriate wage and price proxies currently available to represent the rate of price change for each expenditure category. For the majority of the cost weights, we based the price proxies on Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data and grouped them into one of the following BLS categories:

- Employment Cost Indexes. Employment Cost Indexes (ECIs) measure the rate of change in employment wage rates and employer costs for employee benefits per hour worked. These indexes are fixed-weight indexes and strictly measure the change in wage rates and employee benefits per hour. ECIs are superior to Average Hourly Earnings (AHE) as price proxies for input price indexes because they are not affected by shifts in occupation or industry mix, and because they measure pure price change and are available by both occupational group and by industry. The industry ECIs are based on the NAICS and the occupational ECIs are based on the Standard Occupational Classification System (SOC).

- Producer Price Indexes. Producer Price Indexes (PPIs) measure price changes for goods sold in other than retail markets. PPIs are used when the purchases of goods or services are made at the wholesale level.

- Consumer Price Indexes. Consumer Price Indexes (CPIs) measure change in the prices of final goods and services bought by consumers. CPIs are only used when the purchases are similar to those of retail consumers rather than purchases at the wholesale level, or if no appropriate PPIs are available.

We evaluated the price proxies using the criteria of reliability, timeliness, availability, and relevance:

- Reliability. Reliability indicates that the index is based on valid statistical methods and has low sampling variability. Widely accepted statistical methods ensure that the data were collected and aggregated in a way that can be replicated. Low sampling variability is desirable because it indicates that the sample reflects the typical members of the population. (Sampling variability is variation from the true population parameter that occurs by chance because only a sample was surveyed rather than the entire population.)

- Timeliness. Timeliness implies that the proxy is published regularly, preferably at least once a quarter. The market baskets are updated quarterly and, therefore, it is important for the underlying price proxies to be up-to-date, reflecting the most recent data available. We believe that using proxies that are published regularly (at least quarterly, whenever possible) helps to ensure that we are using the most recent data available to update the market basket. We strive to use publications that are disseminated frequently, because we believe that this is an optimal way to stay abreast of the most current data available.

- Availability. Availability means that the proxy is publicly available. We prefer that our proxies are publicly available because this will help ensure that our market basket updates are as transparent to the public as possible. In addition, this enables the public to be able to obtain the price proxy data on a regular basis.

- Relevance. Relevance means that the proxy is applicable and representative of the cost category weight to which it is applied. The CPIs, PPIs, and ECIs that we selected meet these criteria. Therefore, we believe that they continue to be the best measure of price changes for the cost categories to which they would be applied.

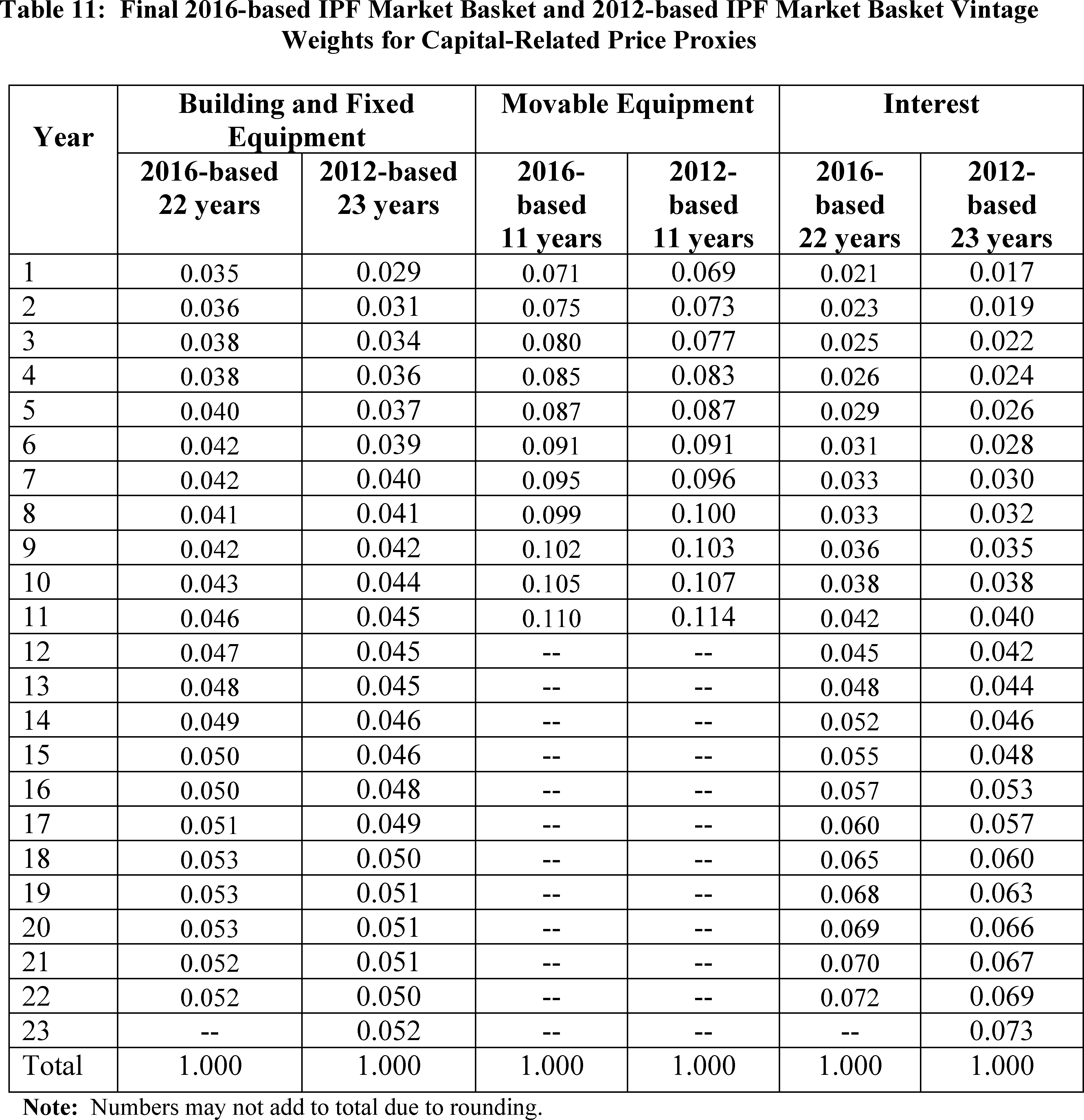

Table 12 lists all price proxies that we proposed to use for the 2016-based IPF market basket. A detailed explanation of the price proxies we proposed for each cost category weight is provided.

i. Price Proxies for the Operating Portion of the 2016-Based IPF Market Basket

Wages and Salaries

There is not a published wage proxy that we believe represents the occupational distribution of workers in IPFs. To measure wage price growth in the proposed 2016-based IPF market basket, we proposed to apply a proxy blend based on six occupational subcategories within the Wages and Salaries category, which would reflect the IPF occupational mix, as done for the 2012-based IPF market basket.

We proposed to use the National Industry-Specific Occupational Employment and Wage estimates for NAICS 622200, Psychiatric & Substance Abuse Hospitals, published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics Office of Occupational Employment Statistics (OES), as the data source for the wage cost shares in the wage proxy blend. We proposed to use May 2016 OES data. Detailed information on the methodology for the national industry-specific occupational employment and wage estimates survey can be found at http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_tec.htm. For the 2012-based IPF market basket, we used May 2012 OES data.

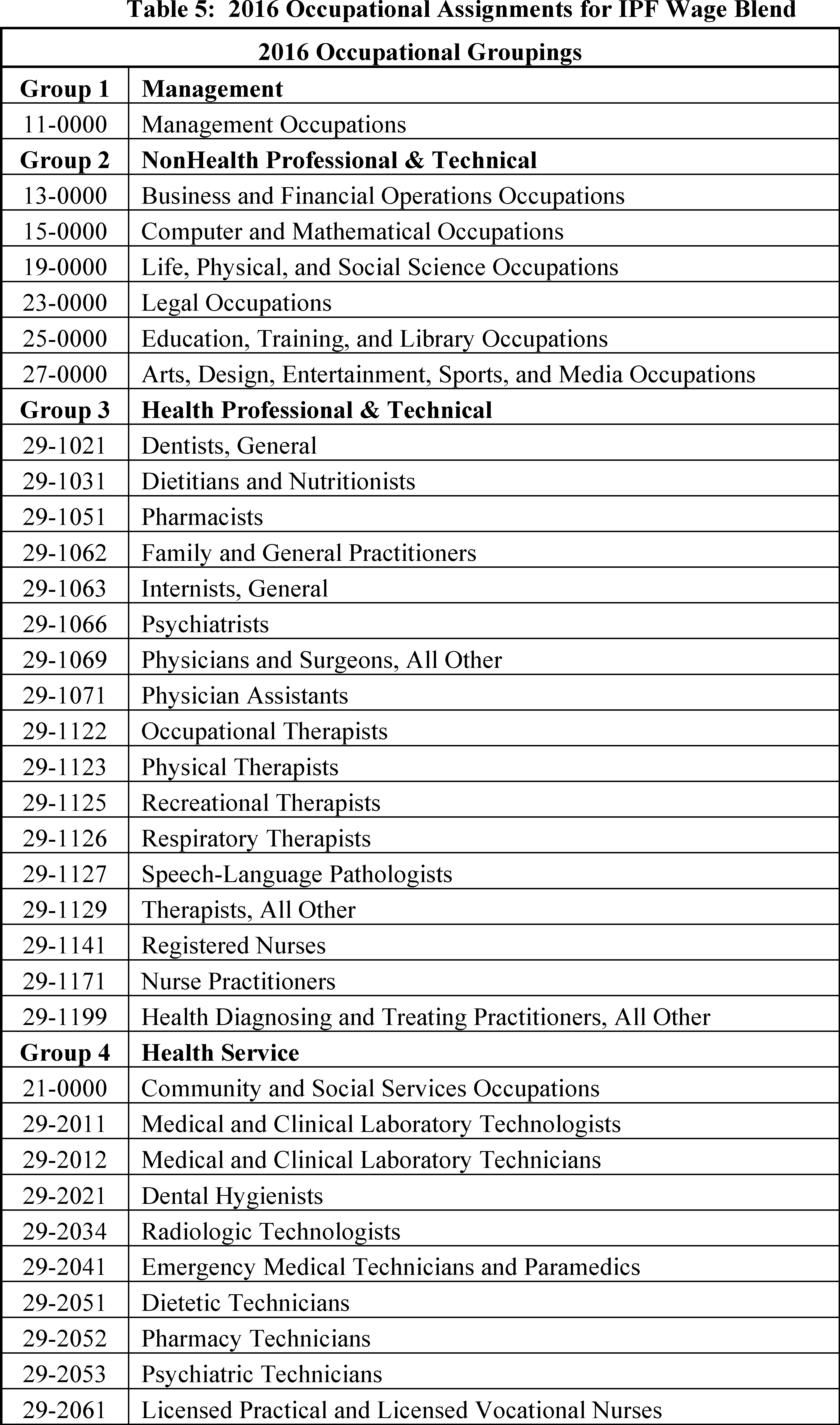

Based on the OES data, there are six wage subcategories: Management; NonHealth Professional and Technical; Health Professional and Technical; Health Service; NonHealth Service; and Clerical. Table 5 lists the 2016 occupational assignments for the six wage subcategories; these are the same occupational groups used in the 2012-based IPF market basket.

Total expenditures by occupation (that is, occupational assignment) were calculated by taking the OES number of employees multiplied by the OES annual average salary. These expenditures were aggregated based on the six groups in Table 5. We next calculated the proportion of each group's expenditures relative to the total expenditures of all six groups. These proportions, listed in Table 6, represent the weights used in the wage proxy blend. We then proposed to use the published wage proxies in Table 6 for each of the six groups (that is, wage subcategories) as we believe these six price proxies are the most technically appropriate indices available to measure the price growth of the Wages and Salaries cost category. These are the same price proxies used in the 2012-based IPF market basket. We did not receive any public comments on the 2016-based IPF wage price proxy. In this final rule, we are finalizing the 2016-based IPF wage price proxy as proposed.

A comparison of the yearly changes from FY 2017 to FY 2020 for the 2016-based IPF wage blend and the 2012-based IPF wage blend is shown in Table 7. The average annual growth rate is the same for both price proxies over 2017-2020.

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Average 2017-2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016-based IPF Final Wage Proxy Blend | 2.4 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 2.8 |

| 2012-based IPF Wage Proxy Blend | 2.4 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 2.8 |

| **Source: IHS Global Inc., 2nd Quarter 2019 forecast with historical data through 1st Quarter 2019. | |||||

Benefits

To measure benefits price growth in the 2016-based IPF market basket, we proposed to apply a benefits proxy blend based on the same six subcategories and the same six blend weights for the wage proxy blend. These subcategories and blend weights are listed in Table 8.

The benefit ECIs, listed in Table 8, are not publically available. Therefore, an “ECIs for Total Benefits” is calculated using publically available “ECIs for Total Compensation” for each subcategory and the relative importance of wages within that subcategory's total compensation. This is the same benefits ECI methodology that we implemented in our 2012-based IPF market basket as well as used in the IPPS, SNF, HHA, RPL, LTCH, and ESRD market baskets. We believe that the six price proxies listed in Table 8 are the most technically appropriate indices to measure the price growth of the Benefits cost category in the proposed 2016-based IPF market basket. We did not receive any public comments on the 2016-based IPF benefit price proxy. In this final rule, we are finalizing the 2016-based IPF benefit price proxy as proposed.

| Wage subcategory | 2016-based benefit blend weight (percent) | 2012-based benefit blend weight (percent) | Price proxy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health Service | 36.3 | 36.2 | ECI for Total Benefits for All Civilian workers in Healthcare and Social Assistance. |

| Health Professional and Technical | 34.9 | 33.5 | ECI for Total Benefits for All Civilian workers in Hospitals. |

| NonHealth Service | 8.9 | 9.2 | ECI for Total Benefits for Private Industry workers in Service Occupations. |

| NonHealth Professional and Technical | 7.0 | 7.3 | ECI for Total Benefits for Private Industry workers in Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services. |

| Management | 6.8 | 7.1 | ECI for Total Benefits for Private Industry workers in Management, Business, and Financial. |

| Clerical | 6.1 | 6.7 | ECI for Total Benefits for Private Industry workers in Office and Administrative Support. |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 |

A comparison of the yearly changes from FY 2017 to FY 2020 for the 2016-based IPF benefit proxy blend and the 2012-based IPF benefit proxy is shown in Table 9. The average annual growth rate is the same for both price proxies over 2017-2020.

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Average 2017-2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016-based IPF Final Benefit Proxy Blend | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 2.4 |

| 2012-based IPF Benefit Proxy Blend | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 2.4 |

| Source: IHS Global Inc., 2nd Quarter 2019 forecast with historical data through 1st Quarter 2019. | |||||

Electricity

We proposed to continue to use the PPI Commodity Index for Commercial Electric Power (BLS series code WPU0542) to measure the price growth of this cost category. This is the same price proxy used in the 2012-based IPF market basket.

Fuel, Oil, and Gasoline

Similar to the 2012-based IPF market basket, for the 2016-based IPF market basket, we proposed to use a blend of the PPI for Petroleum Refineries and the PPI Commodity for Natural Gas. Our analysis of the BEA's 2012 Benchmark I-O data (use table before redefinitions, purchaser's value for NAICS 622000 [Hospitals]) shows that Petroleum Refineries expenses accounts for approximately 90 percent and Natural Gas accounts for approximately 10 percent of Hospitals (NAICS 622000) total Fuel, Oil, and Gasoline expenses. Therefore, we proposed to use a blend of 90 percent of the PPI for Petroleum Refineries (BLS series code PCU324110324110) and 10 percent of the PPI Commodity Index for Natural Gas (BLS series code WPU0531) as the price proxy for this cost category. The 2012-based IPF market basket used a 70/30 blend of these price proxies, reflecting the 2007 I-O data. We believe that these two price proxies continue to be the most technically appropriate indices available to measure the price growth of the Fuel, Oil, and Gasoline cost category in the proposed 2016-based IPF market basket.

Professional Liability Insurance

We proposed to continue to use the CMS Hospital Professional Liability Index to measure changes in professional liability insurance (PLI) premiums. To generate this index, we collect commercial insurance premiums for a fixed level of coverage while holding non-price factors constant (such as a change in the level of coverage). This is the same proxy used in the 2012-based IPF market basket.

Pharmaceuticals

We proposed to continue to use the PPI for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use, Prescription (BLS series code WPUSI07003) to measure the price growth of this cost category. This is the same proxy used in the 2012-based IPF market basket.

Food: Direct Purchases

We proposed to continue to use the PPI for Processed Foods and Feeds (BLS series code WPU02) to measure the price growth of this cost category. This is the same proxy used in the 2012-based IPF market basket.

Food: Contract Purchases

We proposed to continue to use the CPI for Food Away From Home (BLS series code CUUR0000SEFV) to measure the price growth of this cost category. This is the same proxy used in the 2012-based IPF market basket.

Chemicals

Similar to the 2012-based IPF market basket, we proposed to use a four part blended PPI as the proxy for the chemical cost category in the proposed 2016-based IPF market basket. The proposed blend is composed of the PPI for Industrial Gas Manufacturing Primary Products (BLS series code PCU325120325120P), the PPI for Other Basic Inorganic Chemical Manufacturing (BLS series code PCU32518-32518-), the PPI for Other Basic Organic Chemical Manufacturing (BLS series code PCU32519-32519-), and the PPI for Other Miscellaneous Chemical Product Manufacturing (BLS series code PCU325998325998).

We note that the four part blended PPI used in the 2012-based IPF market basket is composed of the PPI for Industrial Gas Manufacturing (BLS series code PCU325120325120P), the PPI for Other Basic Inorganic Chemical Manufacturing (BLS series code PCU32518-32518-), the PPI for Other Basic Organic Chemical Manufacturing (BLS series code PCU32519-32519-), and the PPI for Soap and Cleaning Compound Manufacturing (BLS series code PCU32561-32561-).

We proposed to derive the weights for the PPIs using the 2012 Benchmark I-O data. The 2012-based IPF market basket used the 2007 Benchmark I-O data to derive the weights for the four PPIs.

Table 10 shows the weights for each of the four PPIs used to create proposed blended Chemical proxy for the 2016-based IPF market basket compared to the 2012-based IPF market basket blended Chemical proxy.

| Name | Final 2016-based IPF weights (percent) | 2012-based IPF weights (percent) | NAICS |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPI for Industrial Gas Manufacturing | 19 | 32 | 325120 |

| PPI for Other Basic Inorganic Chemical Manufacturing | 13 | 17 | 325180 |

| PPI for Other Basic Organic Chemical Manufacturing | 60 | 45 | 325190 |

| PPI for Soap and Cleaning Compound Manufacturing | n/a | 6 | 325610 |

| PPI for Other Miscellaneous Chemical Product Manufacturing | 8 | n/a | 325998 |

Medical Instruments

We proposed to continue to use a blend of two PPIs for the Medical Instruments cost category. The 2012 Benchmark I-O data shows an approximate 57/43 split between Surgical and Medical Instruments and Medical and Surgical Appliances and Supplies for this cost category. Therefore, we proposed a blend composed of 57 percent of the commodity-based PPI for Surgical and Medical Instruments (BLS series code WPU1562) and 43 percent of the commodity-based PPI for Medical and Surgical Appliances and Supplies (BLS series code WPU1563). The 2012-based IPF market basket used a 50/50 blend of these PPIs based on the 2007 Benchmark I-O data.

Rubber and Plastics

We proposed to continue to use the PPI for Rubber and Plastic Products (BLS series code WPU07) to measure price growth of this cost category. This is the same proxy used in the 2012-based IPF market basket.

Paper and Printing Products

We proposed to continue to use the PPI for Converted Paper and Paperboard Products (BLS series code WPU0915) to measure the price growth of this cost category. This is the same proxy used in the 2012-based IPF market basket.

Miscellaneous Products

We proposed to continue to use the PPI for Finished Goods Less Food and Energy (BLS series code WPUFD4131) to measure the price growth of this cost category. This is the same proxy used in the 2012-based IPF market basket.

Professional Fees: Labor-Related

We proposed to continue to use the ECI for Total Compensation for Private Industry workers in Professional and Related (BLS series code CIU2010000120000I) to measure the price growth of this category. This is the same proxy used in the 2012-based IPF market basket.

Administrative and Facilities Support Services

We proposed to continue to use the ECI for Total Compensation for Private Industry workers in Office and Administrative Support (BLS series code CIU2010000220000I) to measure the price growth of this category. This is the same proxy used in the 2012-based IPF market basket.

Installation, Maintenance, and Repair

We proposed to continue to use the ECI for Total Compensation for Civilian workers in Installation, Maintenance, and Repair (BLS series code CIU1010000430000I) to measure the price growth of this cost category. This is the same proxy used in the 2012-based IPF market basket.

All Other: Labor-Related Services

We proposed to continue to use the ECI for Total Compensation for Private Industry workers in Service Occupations (BLS series code CIU2010000300000I) to measure the price growth of this cost category. This is the same proxy used in the 2012-based IPF market basket.

Professional Fees: Nonlabor-Related

We proposed to continue to use the ECI for Total Compensation for Private Industry workers in Professional and Related (BLS series code CIU2010000120000I) to measure the price growth of this category. This is the same proxy used in the 2012-based IPF market basket.

Financial Services

We proposed to continue to use the ECI for Total Compensation for Private Industry workers in Financial Activities (BLS series code CIU201520A000000I) to measure the price growth of this cost category. This is the same proxy used in the 2012-based IPF market basket.

Telephone Services

We proposed to continue to use the CPI for Telephone Services (BLS series code CUUR0000SEED) to measure the price growth of this cost category. This is the same proxy used in the 2012-based IPF market basket.

All Other: Nonlabor-Related Services

We proposed to continue to use the CPI for All Items Less Food and Energy (BLS series code CUUR0000SA0L1E) to measure the price growth of this cost category. This is the same proxy used in the 2012-based IPF market basket. We did not receive any public comments on the 2016-based IPF price proxies. In this final rule, we are finalizing the 2016-based IPF price proxies as proposed.

ii. Price Proxies for the Capital Portion of the Proposed 2016-Based IPF Market Basket

Capital Price Proxies Prior to Vintage Weighting

We proposed to continue to use the same price proxies for the capital-related cost categories as were applied in the 2012-based IPF market basket, which are provided and described in Table 12. Specifically, we proposed to proxy:

- Depreciation: Building and Fixed Equipment cost category by BEA's Chained Price Index for Nonresidential Construction for Hospitals and Special Care Facilities (BEA Table 5.4.4. Price Indexes for Private Fixed Investment in Structures by Type).

- Depreciation: Movable Equipment cost category by the PPI for Machinery and Equipment (BLS series code WPU11).

- Nonprofit Interest cost category by the average yield on domestic municipal bonds (Bond Buyer 20-bond index).

- For-profit Interest cost category by the average yield on Moody's Aaa bonds (Federal Reserve).

- Other Capital-Related cost category by the CPI-U for Rent of Primary Residence (BLS series code CUUS0000SEHA).

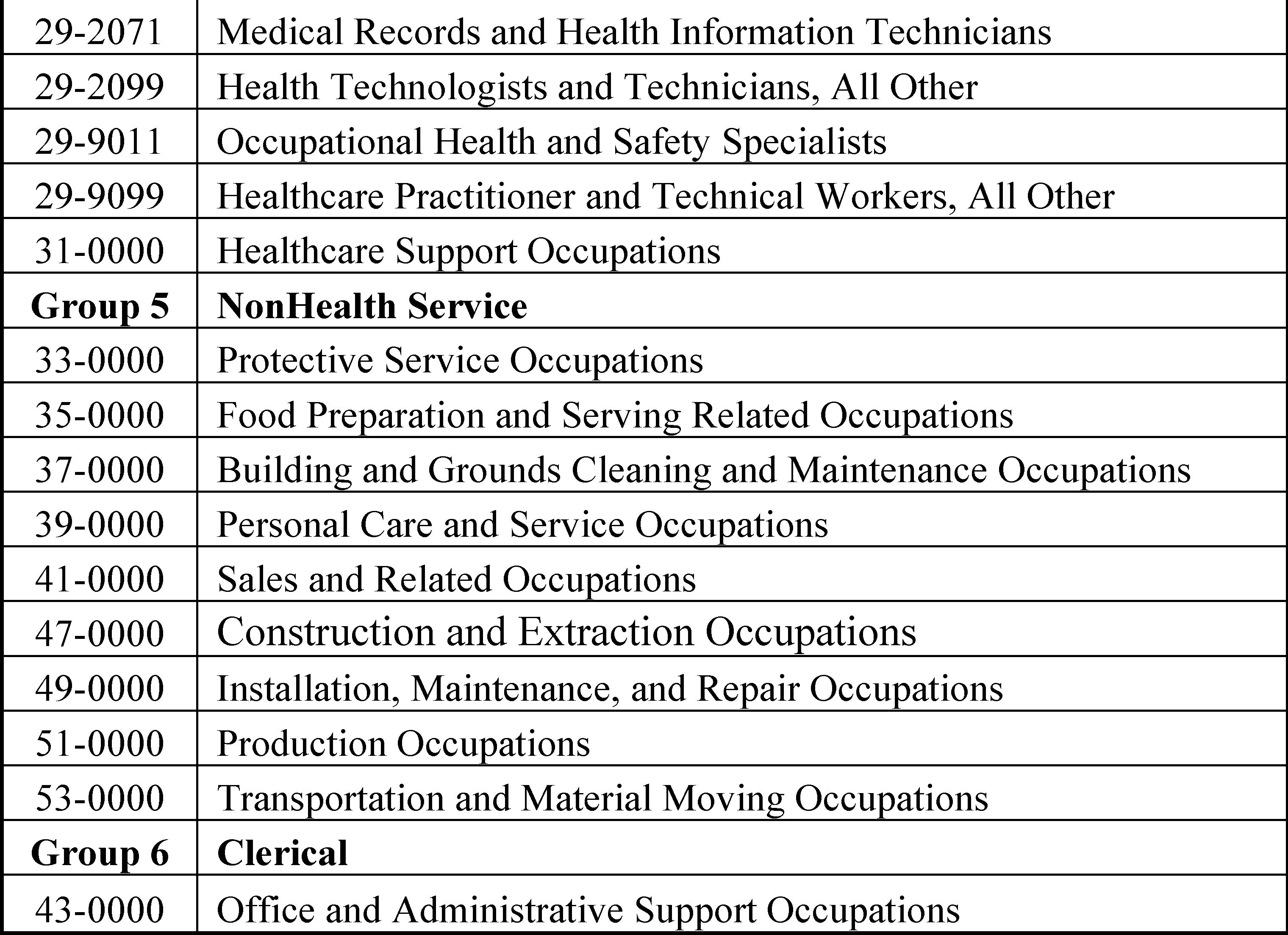

We believe these are the most appropriate proxies for IPF capital-related costs that meet our selection criteria of relevance, timeliness, availability, and reliability. We also proposed to continue to vintage weight the capital price proxies for Depreciation and Interest in order to capture the long-term consumption of capital. This vintage weighting method is similar to the method used for the 2012-based IPF market basket and is described in the section labeled Vintage Weights for Price Proxies.

Vintage Weights for Price Proxies

Because capital is acquired and paid for over time, capital-related expenses in any given year are determined by both past and present purchases of physical and financial capital. The vintage-weighted capital-related portion of the proposed 2016-based IPF market basket is intended to capture the long-term consumption of capital, using vintage weights for depreciation (physical capital) and interest (financial capital). These vintage weights reflect the proportion of capital-related purchases attributable to each year of the expected life of building and fixed equipment, movable equipment, and interest. We proposed to use vintage weights to compute vintage-weighted price changes associated with depreciation and interest expenses.

Capital-related costs are inherently complicated and are determined by complex capital-related purchasing decisions, over time, based on such factors as interest rates and debt financing. In addition, capital is depreciated over time instead of being consumed in the same period it is purchased. By accounting for the vintage nature of capital, we are able to provide an accurate and stable annual measure of price changes. Annual non-vintage price changes for capital are unstable due to the volatility of interest rate changes and, therefore, do not reflect the actual annual price changes for IPF capital-related costs. The capital-related component of the proposed 2016-based IPF market basket reflects the underlying stability of the capital-related acquisition process.