AGENCY:

Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior.

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), determine endangered species status under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (Act), for the southern mountain caribou distinct population segment (DPS) of woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou). This determination amends the current listing of the southern Selkirk Mountains population of woodland caribou by defining the southern mountain caribou DPS. The southern mountain caribou DPS of woodland caribou consists of 17 subpopulations (15 extant and 2 extirpated). This DPS includes the currently listed southern Selkirk Mountains population of woodland caribou, a transboundary population that moves between British Columbia, Canada, and northern Idaho and northeastern Washington, United States. We have determined that the approximately 30,010 acres (12,145 hectares) designated as critical habitat on November 28, 2012, for the southern Selkirk Mountains population of woodland caribou is applicable to the U.S. portion of the endangered southern mountain caribou DPS and, as such, reaffirm the existing critical habitat for the DPS. This rule amends the listing of this DPS on the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife.

DATES:

This rule is effective November 1, 2019.

ADDRESSES:

This final rule is available at http://www.regulations.gov under Docket No. FWS-R1-ES-2012-0097, and at the Service's Idaho Fish and Wildlife Office at http://www.fws.gov/idaho/. Comments and materials we received, as well as supporting documentation we used in preparing this rule, are available for public inspection at http://www.regulations.gov. All of the comments, materials, and documentation that we considered in this rulemaking are available by appointment, during normal business hours at: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Northern Idaho Field Office, 11103 E. Montgomery Drive, Spokane Valley, WA 99206; telephone 509-891-6839; facsimile 509-891-6748.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Greg Hughes, State Supervisor, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Idaho Fish and Wildlife Office, 1387 S. Vinnell Way, Room 368, Boise, ID 83709; telephone 208-378-5243; facsimile 208-378-5262. Persons who are hearing impaired or speech impaired may call the Federal Relay Service at 800-877-8339 for TTY (telephone typewriter or teletypewriter) assistance 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Executive Summary

Why we need to publish a rule. Under the Act, a species may warrant protection through listing if it is endangered or threatened throughout all or a significant portion of its range. Listing a species as an endangered or threatened species can only be completed by rulemaking. Any proposed or final rule designating a DPS as endangered or threatened under the Act should clearly analyze the action using the following three elements: discreteness of the population segment in relation to the remainder of the taxon to which it belongs; the significance of the population segment to the taxon to which it belongs; and the conservation status of the population segment in relation to the Act's standards for listing (DPS policy; 61 FR 4722, February 7, 1996). Under the Act, any species that is determined to be an endangered or threatened species requires critical habitat to be designated, to the maximum extent prudent and determinable. Designations and revisions of critical habitat can only be completed through rulemaking. Here we reaffirm the designation of approximately 30,010 acres (ac) (12,145 hectares (ha)) in one unit within Boundary County, Idaho, and Pend Oreille County, Washington, as critical habitat for the southern mountain caribou DPS.

This rule amends the current listing of the southern Selkirk Mountains population of woodland caribou as follows:

- By defining the southern mountain caribou DPS, which includes the currently listed southern Selkirk Mountains population of woodland caribou;

- By designating the status of the southern mountain caribou DPS as endangered under the Act; and

- By reaffirming the designation of approximately 30,010 ac (12,145 ha) as critical habitat for the southern mountain caribou DPS.

The basis for our action. Section 4 of the Act (16 U.S.C. 1533) and its implementing regulations (50 CFR part 424) set forth the procedures for determining whether a species meets the definition of “endangered species” or “threatened species.” The Act defines an “endangered species” as a species that is “in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range,” and a “threatened species” as a species that is “likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range.” Under the Act, a species may be determined to be an endangered species or threatened species because of any one or a combination of the five factors described in section 4(a)(1): (A) The present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range; (B) overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes; (C) disease or predation; (D) the inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; and (E) other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence. We have determined that threats described under factors A, C, and E pose significant threats to the continued existence of the southern mountain caribou DPS.

We listed the southern Selkirk Mountains population of woodland caribou as endangered under the Act on February 29, 1984 (49 FR 7390). According to our “Policy Regarding the Recognition of Distinct Vertebrate Population Segments Under the Endangered Species Act” (DPS policy; 61 FR 4722, February 7, 1996), the appropriate application of the policy to pre-1996 DPS listings shall be considered in our 5-year reviews of the status of the species. We conducted a DPS analysis during our 2008 5-year review, which concluded that the southern Selkirk Mountains population of woodland caribou met both the discreteness and significance elements of the DPS policy. However, we now recognize that this analysis did not consider the significance of this population relative to the appropriate taxon. The purpose of the DPS policy is to set forth standards for determining which populations of vertebrate organisms that are subsets of species or subspecies may qualify as entities that we may list as endangered or threatened under the Act. In the 2008 5-year review, we assessed the significance of the southern Selkirk Mountains population to the “mountain ecotype” of woodland caribou. The “mountain ecotype” is neither a species nor a subspecies. The appropriate DPS analysis for the southern Selkirk Mountains population of woodland caribou should have been conducted relative to the subspecies woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou). Listing or reclassifying DPSs allows the Service to protect and conserve species and the ecosystems upon which they depend before large-scale decline occurs that would necessitate listing a species or subspecies throughout its entire range.

Peer review and public comment. We sought comments from independent specialists to ensure that our designation is based on scientifically sound data, assumptions, and analyses. We invited these peer reviewers to comment on our amended listing proposal. We also considered all comments and information we received during the comment period.

Summary of Changes From the Proposed Rule

Based on information we received in comments regarding how we described the coat color of caribou during breeding and winter, we modified our description to reflect that caribou coat color and pattern is variable (Geist 2007) and winter pelage varies from almost white to dark brown (see Species Information under Background, below).

In our May 8, 2014, proposed rule (79 FR 26504), we noted that woodland caribou populations can be further broken down into subunits called “local populations.” The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) (2014, entire) uses the term “subpopulation” to refer to the same population subunits in Canada. In order to minimize confusion, we have conformed our terminology to that used by COSEWIC. Therefore, our proposed rule uses “subpopulations,” instead of “local populations,” to describe caribou subunits.

Caribou subpopulations represent groupings of individual woodland caribou that have overlapping ranges/movement patterns and breed with one another more frequently than they breed with caribou from other subpopulations. Subpopulations in southern British Columbia are thought to be a relatively recent phenomena resulting from habitat fragmentation and loss within the population of woodland caribou; historically, movement of caribou between subpopulations was likely.

Within the Status of the Southern Mountain Caribou DPS discussion in this final rule, we provide clarification on the number and names of subpopulations (both extant and recently extirpated) within the DPS, and describe how subpopulation names and groupings of subpopulations by Canada have changed through time. We also clarify that the range of the DPS in British Columbia, Canada, and the United States has declined by 60 percent since historical arrival of Europeans in British Columbia, according to Spalding (2000, p. 40). In our May 8, 2014 proposed rule (79 FR 26504), we stated the range of the DPS had declined by 40 percent, but this was specific to the British Columbia, Canada, portion of the DPS's range (i.e., it did not include the portion of the range in the United States).

We updated the status of the southern mountain caribou DPS to reflect the most recent information contained in the COSEWIC report (2014, entire) pertaining to the number of individual caribou in each of the 15 extant subpopulations and the total estimated number of individuals in the DPS. We corrected the trend status of the Hart Ranges subpopulation to reflect that it is now declining, and to reflect that the overall trend of the DPS is declining and the rate of decline is accelerating. We also included additional information pertaining to population viability analyses conducted by Hatter (2006, entire, in litt.) and Wittmer (2010, entire) assessing the extinction risk of subpopulations within the DPS.

We provided additional analysis pertaining to the isolation of subpopulations within the DPS as well as separation from other populations (i.e., Designatable Units) of woodland caribou in Canada. We explained how this isolation may affect the ability of the subpopulations within the DPS to function as a metapopulation, which could adversely affect the demographic and/or genetic stability or rescue of subpopulations within the DPS. We also provided additional analyses on potential threats to the DPS related to renewable energy and industrial development, and effect of predation upon the current and future status of the DPS.

We included additional information pertaining to Canadian conservation efforts for woodland caribou, which include augmenting animals into the Purcells South subpopulation and wolf control efforts within several subpopulations within the DPS (under the Factor A analysis, below, see Efforts in Canada under “Conservation Efforts to Reduce Habitat Destruction, Modification, or Curtailment of Its Range”). We also included additional information pertaining to existing regulations enacted by the British Columbia provincial government that can be utilized to protect southern mountain caribou and their habitat, as well as implementing programs and projects for their conservation (see “Canada” under Factor D analysis, below).

In our May 8, 2014, proposed rule (79 FR 26504), we stated that further evaluation of existing regulatory mechanisms (Factor D) was needed before a final determination could be made as to the adequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms to address the threats affecting the status of the DPS. Notwithstanding the additional information learned regarding existing provincial laws and regulations of British Columbia, Canada, we conclude that, while the existing regulatory mechanisms in the United States and Canada enable the United States and Canada to ameliorate to some extent the identified threats to the southern mountain caribou DPS, the existing mechanisms do not completely alleviate the potential for the identified threats to affect the status of southern mountain caribou and their habitat.

In our May 8, 2014, proposed rule (79 FR 26504), we proposed to list the southern mountain caribou DPS as threatened. However, we have now determined that the status of, and threats to, the southern mountain caribou DPS warrant its listing as endangered. This determination is based on (1) the additional analysis referenced above and contained in the Status of the Southern Mountain Caribou DPS discussion below; and (2) the discussions of factors A (the present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range), C (disease or predation), D (inadequacy of regulatory mechanisms) and E (other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence) in this final rule. The rationale for endangered status is summarized within the Determination section of this final rule. The May 8, 2014, proposed rule also contained a “Significant Portion of the Range” (SPR) analysis. That analysis was included in the proposed rule to conform to Service policy for listing rules at that time. However, subsequent to publishing the proposed rule, the Service revised its policy on when it is necessary to perform a SPR analysis (79 FR 37578, July 1, 2014).

In this case, because we found that the southern mountain DPS of woodland caribou is in danger of extinction throughout all of its range, per the Service's SPR Policy (79 FR 37578, July 1, 2014), the protections of the Act apply to each individual member of the DPS wherever found. Consequently, an analysis of whether there is any significant portion of its range where the species is in danger of extinction or likely to become so in the foreseeable future was unnecessary and was not conducted.

Background

Previous Federal Actions

Please refer to the proposed amended listing rule for the southern mountain caribou DPS (79 FR 26504; May 8, 2014) for a detailed description of previous Federal actions concerning this species. The May 8, 2014, proposed rule opened a 60-day public comment period, ending July 7, 2014. On June 10, 2014, we extended the public comment period on the proposed amended listing rule until August 6, 2014, and announced two public informational sessions and hearings (79 FR 33169). Public informational sessions and hearings were held in Sandpoint, Idaho, on June 25, 2014, and in Bonners Ferry, Idaho, on June 26, 2014 (79 FR 33169). On March 24, 2015, we reopened the public comment period on the proposed amended listing rule for an additional 30 days, ending on April 23, 2015, to allow the public time to review new information: A report from COSEWIC [1] and associated literature, which we received after the previous public comment period (80 FR 15545).

In our May 8, 2014, proposed rule (79 FR 26504), we proposed to reaffirm the November 28, 2012, final critical habitat designation (77 FR 71042) for the southern Selkirk Mountains population of woodland caribou as it applies to the U.S. portion of the endangered southern mountain DPS of woodland caribou. However, on March 23, 2015, the Idaho District Court (Center for Biological Diversity v. Kelly, 93 F.Supp.3d 1193 (D. Idaho, 2015)) ruled that we made a procedural error in not providing public review and comment regarding considerations we made related to our final critical habitat designation (77 FR 71042). On April 19, 2016, in response to the court's order, we published a document in the Federal Register (81 FR 22961) that reopened the public comment period on the November 28, 2012, final designation of critical habitat (77 FR 71042), which we proposed to reaffirm in the May 8, 2014, proposed rule (79 FR 26504) as the critical habitat for the southern mountain caribou DPS. We received numerous comments regarding critical habitat during the initial public comment periods for the proposed amended listing rule; we are addressing those comments in this final rule as well as new comments we received during the reopened public comment period on the November 28, 2012, final critical habitat designation.

Species Information

Please refer to the proposed listing rule for the southern mountain caribou DPS (79 FR 26504; May 8, 2014) for a summary of species information. Except for the following correction, there are no changes to the species information provided in that proposed rule. The sentence reading, “Their winter pelage varies from nearly white in Arctic caribou such as the Peary caribou, to dark brown in woodland caribou (COSEWIC 2011, pp. 10-11)” at 79 FR 26507 should instead read, “Breeding pelage is variable in color and patterning (Geist 2007), and winter pelage varies from almost white to dark brown.”

Evaluation of the Southern Mountain Caribou as a Distinct Population Segment

Introduction and Background

The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and the Service published a joint “Policy Regarding the Recognition of Distinct Vertebrate Population Segments Under the Endangered Species Act” (DPS Policy) on February 7, 1996 (61 FR 4722). According to the DPS policy, any proposed or final rule designating a DPS as endangered or threatened under the Act should clearly analyze the action using the following three elements: Discreteness of the population segment in relation to the remainder of the taxon to which it belongs; the significance of the population segment to the taxon to which it belongs; and the conservation status of the population segment in relation to the Act's standards for listing. If the population segment qualifies as a DPS, the conservation status of that DPS is then evaluated to determine whether it is endangered or threatened.

A population segment of a vertebrate species may be considered discrete if it satisfies either one of the following conditions: (1) It is markedly separated from other populations of the same taxon as a consequence of physical, physiological, ecological, or behavioral factors; or (2) it is delimited by international governmental boundaries within which differences in control of exploitation, management of habitat, conservation status, or regulatory mechanisms exist that are significant in light of section 4(a)(1)(D) of the Act.

If a population is found to be discrete, then it is evaluated for significance under the DPS policy on the basis of its importance to the taxon to which it belongs. This consideration may include, but is not limited to, the following: (1) Persistence of the discrete population segment in an ecological setting unusual or unique to the taxon; (2) evidence that loss of the discrete population segment would result in a significant gap in the range of the taxon; (3) evidence that the population represents the only surviving natural occurrence of the taxon that may be more abundant elsewhere as an introduced population outside of its historical range; or (4) evidence that the population differs markedly from other populations of the species in its genetic characteristics.

If a population segment is both discrete and significant (i.e., it qualifies as a potential DPS), its evaluation for endangered or threatened status is based on the Act's definitions of those terms and a review of the factors listed in section 4(a) of the Act. According to our DPS policy, it may be appropriate to assign different classifications to different DPSs of the same vertebrate taxon.

Section 3(16) of the Act defines the term “species” to include “any subspecies of fish or wildlife or plants, and any distinct population segment of any species of vertebrate fish or wildlife which interbreeds when mature.” We have always understood the phrase “interbreeds when mature” to mean that a DPS must consist of members of the same species or subspecies in the wild that would be biologically capable of interbreeding if given the opportunity, but all members need not actually interbreed with each other. A DPS is a subset of a species or subspecies, and cannot consist of members of a different species or subspecies. A DPS may include multiple populations of vertebrate organisms that may not necessarily interbreed with each other. For example, a DPS may consist of multiple populations of a fish species separated into different drainages. While these populations may not actually interbreed with each other, their members are biologically capable of interbreeding.

Distinctive, discrete, and significant populations of the woodland caribou have been identified, described, and assessed by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). COSEWIC is composed of qualified wildlife experts drawn from Federal, provincial, and territorial governments; wildlife management boards; Aboriginal groups; universities; museums; national nongovernmental organizations; and others with expertise in the conservation of wildlife species in Canada. The role of COSEWIC is to assess and classify, using the best available information, the conservation status of wildlife species, subspecies, and separate populations suspected of being at risk. In addition, they make species status recommendations to the Canadian government and the public. Once COSEWIC makes this recommendation, it is the option of the Canadian Federal government to decide whether a species will be listed under Canada's Species At Risk Act (SARA). The southern mountain caribou population, which includes the transboundary southern Selkirk Mountains population of woodland caribou (and is the subject of this final amended listing), is currently designated as “threatened” under SARA (COSEWIC 2011, p. 74). This designation was reached because the population of southern mountain caribou is mostly made up of small, increasingly isolated herds (most of which are in decline) with an estimated range reduction of up to 40 percent from their historical range (COSEWIC 2002, p. 58; COSEWIC 2011, p. 74).

In August 2014, COSEWIC, in accordance with SARA, submitted its assessment to the Canadian Federal Environment Minister for consideration of changing the legal status of the southern mountain caribou in Canada under SARA to endangered (COSEWIC 2014, p. iv). The recommended change in the legal status under SARA is pending review and decision by the Federal Environment Minister.

Because we now consider the southern Selkirk Mountains population of woodland caribou part of the larger southern mountain caribou population, as recognized by COSEWIC (2011, entire), we recognize that our evaluation of the southern Selkirk Mountains population is more appropriately conducted at the scale of the larger southern mountain caribou population. Therefore, below we evaluate whether, under our DPS policy, the southern mountain caribou population segment (i.e., 15 extant and 2 extirpated subpopulations) of woodland caribou occurring in British Columbia, Canada, and northeastern Washington and northern Idaho, United States, qualifies as a DPS under the Act.

We completed a 5-year review of the endangered southern Selkirk Mountains population of woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) in 2008 (USFWS 2008). Because this population was listed prior to the Service's 1996 DPS policy (61 FR 4722; February 7, 1996), the 5-year review included an analysis of this population in relation to the DPS policy. In conducting the DPS analysis, we considered the discreteness and significance of this population in relation to the mountain caribou metapopulation (USFWS 2008, pp. 6-13) (i.e., mountain caribou ecotype). From this analysis, we concluded that the southern Selkirk Mountains population of woodland caribou met both the discreteness and significance elements of the DPS policy and was a distinct population segment of the mountain caribou metapopulation (USFWS 2008, p. 13). However, we acknowledged in our December 19, 2012, 90-day finding (77 FR 75091) on a petition to delist the southern Selkirk Mountains population of woodland caribou that the DPS analysis in our 2008 5-year review was not conducted relative to the appropriate taxon. Specifically, we should have conducted the DPS analysis of the southern Selkirk Mountains population of woodland caribou relative to the woodland caribou subspecies (Rangifer tarandus caribou) instead of the mountain caribou metapopulation.

For this final amended listing and DPS analysis of the southern mountain population of woodland caribou to the subspecies woodland caribou, we reviewed and evaluated information contained in numerous publications and reports, including, but not limited to: Banfield 1961; Stevenson et al. 2001; COSEWIC 2002, 2011, 2014; Cichowski et al. 2004; Wittmer et al. 2005b, 2010; Hatter 2006, in litt.; Geist 2007; van Oort et al. 2011; and Serrouya et al. 2012.

In 2002 and 2011, COSEWIC completed status assessments of caribou subspecies and species populations in North America. The 2002 COSEWIC Report evaluated woodland caribou “nationally significant populations” (NSPs). The more recent COSEWIC (2011) Report described “Designatable Units” (DUs) as the appropriate “discrete and significant units” useful to conserve and manage caribou populations throughout Canada. Information used in COSEWIC's 2011 report is useful to our DPS analysis. Canada's DUs are identified based on the criteria that there are “discrete and evolutionarily significant units of a taxonomic species, where `significant' means that the unit is important to the evolutionary legacy of the species as a whole and if lost, would likely not be replaced through natural dispersion” (COSEWIC 2011, p. 14). They consider a population or group of populations to be “discrete” based on the following criteria: distinctiveness in genetic characteristics or inherited traits, habitat discontinuity, or ecological isolation (COSEWIC 2011, p. 15).

It should be noted that COSEWIC's DU designation does not necessarily consider the conservation status or threats to the persistence of caribou DUs. Consistent with its 2009 guidelines, the COSEWIC used five lines of evidence to determine caribou DUs; these include: (1) Phylogenetics; (2) genetic diversity and structure; (3) morphology; (4) movements, behavior, and life-history strategies; and (5) distribution (COSEWIC 2011, p. 15). As a general rule, a DU was designated when several lines of evidence provided support for discreteness and significance (COSEWIC 2011, pp. 15-16). Twelve caribou DUs were classified by COSEWIC in 2011, including the southern mountain caribou population (DU9), which includes the southern Selkirk Mountains population of woodland caribou (COSEWIC 2011, p. 21). The information used to describe the southern mountain DU is reviewed and evaluated in our DPS analysis, as it includes numerous local woodland caribou populations that all possess similar and unique foraging, migration, and habitat use behaviors, and that are geographically separated from other caribou DUs.

Discreteness

As outlined in our 1996 DPS policy, a population segment of a vertebrate species may be considered discrete if it satisfies either one of the following conditions: (1) It is markedly separated from other populations of the same taxon as a consequence of physical, physiological, ecological, or behavioral factors; or (2) it is delimited by international governmental boundaries within which differences in control of exploitation, management of habitat, conservation status, or regulatory mechanisms exist that are significant in light of section 4(a)(1)(D) of the Act.

I. Physical (Geographic) Discreteness

The southern Selkirk Mountains population of woodland caribou is 1 of 17 woodland caribou subpopulations (15 extant, 2 extirpated) (COSEWIC 2014, p. xix) that share distinct foraging, migration, and habitat use behaviors. These subpopulations are all located in steep, mountainous terrain in central and southeastern British Columbia, Canada, and in extreme northeastern Washington and northern Idaho, United States. Little to no dispersal has been detected between these subpopulations and other caribou populations/subpopulations outside this geographic area (Wittmer et al. 2005b, pp. 408, 409; COSEWIC 2011, p. 49; van Oort et al. 2011, pp. 222-223), indicating that mountain caribou appear to lack the inherent behavior to disperse long distances (van Oort, et al. 2011, pp. 215, 221-222). For the purposes of this DPS analysis, this collection of woodland caribou subpopulations, which, as noted above, includes the southern Selkirk Mountains population, constitutes the southern mountain population of caribou; we also refer to it herein as “southern mountain caribou.”

Telemetry research by Wittmer et al. (2005b) and van Oort et al. (2011) supports the physical (geographic) discreteness of southern mountain caribou. One exception is that there is some limited annual range overlap between a few local caribou populations at the far north of the southern mountain caribou population. Although all caribou and reindeer worldwide are considered to be the same species (Rangifer tarandus) and are presumed able to interbreed and produce offspring (COSEWIC 2002, p. 9), the distribution of the southern mountain caribou does not overlap with other caribou populations during the rut or mating season (COSEWIC 2011, p. 50). Previous telemetry studies were completed by Apps and McLellan (2006, pp. 84-85, 92) to determine occupancy across differing landscapes. These studies confirmed that woodland caribou within the geographic area that defines the southern mountain caribou population are strongly associated with the steep, mountainous terrain characterizing the “interior wet-belt” of British Columbia (Stevenson et al. 2001, p. 3), located west of the continental divide. This area is influenced by Pacific air masses that produce the wettest climate in the interior of British Columbia (Stevenson et al. 2001, p. 3). Forests consist of Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii or P. glauca x engelmannii)/subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa) at high elevation, and western red cedar (Thuja plicata)/western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla) at lower elevations. Snowpack typically averages 5 to 16 feet (ft) (2 to 5 meters (m)) in depth (Stevenson et al. 2001, p. 4; COSEWIC 2011, p. 50). Apps and McLellan (2006, p. 92) noted that the steep, complex topography within the interior wet-belt provides seasonally important habitats. Caribou access this habitat by migrating in elevational shifts rather than through the long horizontal migrations of other subspecies in northern Canada. Woodland caribou that live within this interior wet-belt of southern British Columbia, northeastern Washington, and northern Idaho are strongly associated with old-growth forested landscapes (Apps et al. 2001, pp. 65, 70). These landscapes are predominantly cedar/hemlock and spruce/subalpine fir composition (Stevenson et al. 2001, pp. 3-5; Apps and McLellan 2006, pp. 84, 91; Cichowski et al. 2004, pp. 224, 231; COSEWIC 2011, p. 50) that supports woodland caribou's late-winter diet consisting almost entirely of arboreal hair lichens (Cichowski et al. 2004, p. 229).

The southern mountain caribou population is markedly separate from other populations of woodland caribou as a result of physical (geographic) factors. The distribution of this population is primarily located within the interior wet-belt of southern British Columbia, occurring west of the continental divide and generally south of Reynolds Creek (which is about 90 miles (mi) (150 kilometers (km)) north of Prince George, British Columbia). Its geographic range is such that it does not reproduce with other subpopulations of woodland caribou.

II. Behavioral Discreteness

In addition to being physically (geographically) discrete, individuals within the southern mountain caribou population are behaviorally distinguished from woodland caribou in other populations (including the neighboring Northern Mountain and Central Mountain populations). Southern mountain caribou uniquely use steep, high-elevation, mountainous habitats with deep snowfall (about 5 to 16 ft (2 to 5 m)) (COSEWIC 2011, p. 50), and, as described below, are the only woodland caribou that depend on arboreal lichens for forage. This habitat use contrasts with the behavior of other woodland caribou, which occupy relatively drier habitats that receive less snowfall. With less snowfall in these areas, these woodland caribou primarily forage on terrestrial lichens, accessing them by “cratering” or digging through the snow with their hooves (Thomas et al. 1996, p. 339; COSEWIC 2002, pp. 25, 27).

Extreme, deep snow conditions have led to a foraging strategy by the southern mountain caribou that is unique among woodland caribou. They rely exclusively on arboreal (tree) lichens for 3 or more months of the year (Servheen and Lyon 1989, p. 235; Edmonds 1991, p. 91; Stevenson et al. 2001, p. 1; Cichowski et al. 2004, pp. 224, 230-231; MCST 2005, p. 2; COSEWIC 2011, p. 50). Arboreal lichens are a critical winter food for the southern mountain caribou from November to May (Servheen and Lyon 1989, p. 235; Stevenson et al. 2001, p. 1; Cichowski et al. 2004, p. 233). During this time, a southern mountain caribou's diet can be composed almost entirely of these lichens. Arboreal lichens are pulled from the branches of conifers, picked from the surface of the snow after being blown out of trees by wind, or are grazed from wind-thrown branches and trees. The two kinds of arboreal lichens commonly eaten by the southern mountain caribou are Bryoria spp. and Alectoria sarmentosa. Both are extremely slow-growing lichens most commonly found in high-elevation, old-growth conifer forests that are greater than 250 years old (Paquet 1997, p. 14; Apps et al. 2001, pp. 65-66).

Another unique behavior of caribou within the southern mountain caribou population is their altitudinal migrations. They may undertake as many as four of these migrations per year (COSEWIC 2011, p. 50). After wintering at high elevations as described above, at the onset of spring, these caribou move to lower elevations where snow has melted to forage on new green vegetation (Paquet 1997, p. 16; Mountain Caribou Technical Advisory Committee (MCTAC) 2002, p. 11). Pregnant females will move to these spring habitats for forage. During the calving season, sometime from June into July, the need to avoid predators influences habitat selection. Areas selected for calving are typically high-elevation, alpine and non-forested areas in close proximity to old-growth forest ridge tops, as well as high-elevation basins. These high-elevation sites can be food limited, but are more likely to be free of predators (USFWS 1994a, p. 8; MCTAC 2002, p. 11; Cichowski et al. 2004, p. 232; Kinley and Apps 2007, p. 16). During calving, arboreal lichens become the primary food source for pregnant females at these elevations. This is because green forage is largely unavailable in these secluded, old-growth conifer habitats.

During summer months, southern mountain caribou move back to upper-elevation spruce/alpine fir forests (Paquet 1997, p. 16). Summer diets include selective foraging of grasses, flowering plants, horsetails, willow and dwarf birch leaves and tips, sedges, lichens (Paquet 1997, pp. 13, 16), and huckleberry leaves (U.S. Forest Service (USFS) 2004, p. 18). The fall and early winter diet consists largely of dried grasses, sedges, willow and dwarf birch tips, and arboreal lichens.

The southern mountain caribou are behaviorally adapted to the steep, high-elevation, mountainous habitat with deep snowpack. They feed almost exclusively on arboreal lichens for 3 or more months out of the year. They are also reproductively isolated, due to their behavior and separation from other caribou populations during the fall rut and mating season (COSEWIC 2011, p. 50). Based on these unique adaptations, we consider the southern mountain caribou population to meet the behavioral “discreteness” standard in our DPS policy.

III. Genetic Discreteness

Data from Serrouya et al. (2012, p. 2,594) show that genetic population structure (i.e., patterning or clustering of the genetic make-up of individuals within a population) does exist within woodland caribou. Specifically, Serrouya revealed a genetic cluster that is unique to southern mountain caribou and different from genetic clusters found in surrounding subpopulations of woodland caribou designated as part of other Canada caribou DUs (i.e., Central Mountain DU, Northern Mountain DU, and Boreal DU). However, Serrouya also revealed genetic clusters that occur in both the southern mountain caribou and neighboring DUs that suggest some historical gene flow did occur in the past, meaning that historically, caribou moved between populations of these DUs and interbred when mature.

This cluster overlap of DU boundaries is not surprising, as genetic structure is reflective of long-term historical population dynamics and does not necessarily depict current gene flow. Indeed, it does appear that recent impediments to gene flow may be genetically isolating woodland caribou in the southwest portion of their range (Wittmer et al. 2005b, p. 414; van Oort et al. 2011, p. 221; Serrouya et al. 2012, p. 2,598). These impediments include anthropogenic habitat fragmentation and widespread caribou population declines. Therefore, genetic specialization related to unique behaviors and habitat use may represent a relatively recent life-history characteristic (Weckworth et al. 2012, p. 3,620). Historical gene flow between subpopulations of southern mountain caribou and neighboring subpopulations did occur in the past. However, study results from Serrouya et al. (2012), combined with telemetry data from Wittmer et al. (2005b, p. 414) and van Oort et al. (2011, p. 221), suggest that isolation of subpopulations is now the norm, effecting some genetic differentiation of these subpopulations through genetic drift (Serrouya et al. 2012, p. 2,597).

A certain level of genetic differentiation does exist between the southern mountain caribou population and neighboring woodland caribou. However, we do not presently consider there to be sufficient evidence to determine that the southern mountain caribou are genetically isolated from other populations of caribou, particularly the Central Mountain population. Therefore, at this time, we do not find that this population meets the genetic “discreteness” standard in our DPS policy.

IV. Discreteness Conclusion

In summary, we determine that the best available information indicates that the southern mountain caribou, comprised of 17 woodland caribou subpopulations (15 extant and 2 extirpated) that occur in southern British Columbia, northeastern Washington, and northern Idaho, is markedly separated from all other populations of woodland caribou. The southern mountain caribou population is physically (geographically), behaviorally, and reproductively isolated from other woodland caribou. Therefore, we consider the southern mountain caribou population to be discrete per our DPS policy.

Significance

Under our DPS policy, once we have determined that a population segment is discrete, we consider its biological and ecological significance to the larger taxon to which it belongs. Significance is not determined by a quantitative analysis, but is instead a qualitative finding. It will vary from species to species and cannot be reduced to a simple formula or flat percentage. Our DPS policy provides several potential considerations that may demonstrate the significance of a population segment to the species to which it belongs. These considerations include, but are not limited to: (1) Persistence of the discrete population segment in an ecological setting unusual or unique for the taxon; (2) evidence that the discrete population segment differs markedly from other population segments in its genetic characteristics; (3) evidence that the population segment represents the only surviving natural occurrence of the taxon that may be more abundant elsewhere as an introduced population outside its historical range; and (4) evidence that loss of the discrete population segment would result in a significant gap in the range of the taxon. The following discussion addresses considerations regarding the significance of the southern mountain caribou population to the subspecies woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou).

I. Persistence of the Discrete Population Segment in an Ecological Setting Unusual or Unique for the Taxon

As previously discussed, woodland caribou within the southern mountain caribou population are distinguished from woodland caribou in other areas. Southern mountain caribou live in, and are behaviorally adapted to, a unique ecological setting characterized by high-elevation, high-precipitation, and steep old-growth conifer forests that support abundant arboreal lichens (COSEWIC 2011, p. 50). In addition, all woodland caribou in the southern mountain caribou population exhibit a distinct behavior. Specifically, they spend the winter months in high-elevation, steep, mountainous habitats where individuals stand on the deep, hard-crusted snowpack and feed exclusively on arboreal lichens on standing or fallen old-growth conifer trees (Cichowski et al. 2004, pp. 224, 230-231; MCST 2005, p. 2; COSEWIC 2011, p. 50). This behavior is unlike that of woodland caribou in neighboring areas that occupy less steep, drier terrain and do not feed on arboreal lichens during the winter (Thomas et al. 1996, p. 339; COSEWIC 2011, p. 50).

In addition to persisting in a specific environment characterized by steep, high-elevation, old-growth forests and being reliant on arboreal lichens as primary winter forage, caribou of the southern mountain population make relatively short-distance altitudinal migrations up to four times per year. These caribou occupy valley bottoms and lower slopes in the early winter, and ridge tops and upper slopes in later winter after the snowpack deepens and hardens. In the spring, they move to lower elevations again to access green vegetation. Females make solitary movements back to high elevations to calve. This habitat and behavior are unique to the southern mountain caribou population. All other populations within the woodland caribou subspecies occupy winter habitat characterized by gentler topography, lower elevation, and less winter snowpack (COSEWIC 2011, pp. 43, 46) where their primary winter forage, terrestrial (ground) lichens, is most accessible (Thomas et al. 1996, p. 339; COSEWIC 2011, pp. 43, 46). Unlike woodland caribou of the southern mountain population, some populations in eastern Canada (Eastern Migratory DU (DU4; COSEWIC 2011, p. 34)) will migrate relatively long distances across the landscape between wintering and calving habitat, where they will calve in large aggregated groups (COSEWIC 2011, pp., 33, 37; Abraham et al. 2012, p. 274).

We conclude that the southern mountain caribou meets the definition of significant in accordance with our DPS policy, as this population currently persists in an ecological setting unusual or unique for the subspecies of woodland caribou.

II. Evidence That the Discrete Population Segment Differs Markedly From Other Population Segments in Its Genetic Characteristics

Research by Serrouya et al. (2012, p. 2594) indicates that there is some genetic population structure between woodland caribou populations in western North America. This research identified two main genetic clusters within the southern mountain caribou, separated from each other by the North Thompson Valley in British Columbia. One of these clusters is unique, with few exceptions, to the southern mountain caribou (structure analysis; Serrouya et al. 2012, p. 2594). The other cluster, northwest of the North Thompson Valley, is shared with the adjacent Central Mountain population. As such, there is limited genetic evidence in this study that southern mountain caribou populations north of the North Thompson Valley are genetically unique relative to caribou of the Central Mountain population.

As previously discussed, the best available information indicates that recent impediments to gene flow such as habitat fragmentation and widespread caribou population declines may be genetically isolating woodland caribou in the southwestern portion of their range (Wittmer et al. 2005b, p. 414; van Oort et al. 2011, p. 221; Serrouya et al. 2012, p. 2,598). This genetic isolation has resulted in unique behaviors and habitat use (Weckworth et al. 2012, p. 3,620). Study results from Serrouya et al. (2012), combined with telemetry data from Wittmer et al. (2005b, p. 414) and van Oort et al. (2011, p. 221), suggest that while historical gene flow between subpopulations of southern mountain caribou and neighboring subpopulations did occur in the past, isolation of these subpopulations is now the norm. Research into the genetics of the woodland caribou will likely continue and will provide further insight into gene flow between these populations.

Despite some level of genetic differentiation between the southern mountain caribou population and neighboring woodland caribou, and a predicted continuation of genetic differentiation between subpopulations within southern mountain caribou, we do not presently consider southern mountain caribou “genetically unique.” Therefore, at this time we do not find this population meets the genetic “significance” standard in our DPS policy.

III. Evidence That the Population Segment Represents the Only Surviving Natural Occurrence of a Taxon That May Be More Abundant Elsewhere as an Introduced Population Outside Its Historic Range

All caribou in the world are one species (Rangifer tarandus). In a global review of taxonomy of the genus Rangifer, Banfield (1961) documented the occurrence of five subspecies in North America. Woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou), one of the five recognized subspecies of caribou, are the southern-most subspecies in North America. The range of woodland caribou extends in an east/west band from eastern Newfoundland and northern Quebec, all the way into western British Columbia. Southern mountain caribou represent a discrete subset of this subspecies. Because southern mountain caribou are not the only surviving natural occurrence of the woodland caribou subspecies, this element is not applicable.

IV. Evidence That Loss of the Discrete Population Segment Would Result in a Significant Gap in the Range of the Taxon

Historically, woodland caribou were widely distributed throughout portions of the northern tier of the coterminous United States from Washington to Maine, as well as throughout most of southern Canada (COSEWIC 2002, p. 19). However, as a result of habitat loss and fragmentation, overhunting, and the effects of predation, the population of woodland caribou within the British Columbia portion of their range has declined dramatically with an estimated 40 percent range reduction (COSEWIC 2002, p. 20). Additionally, Hatter (pers. comm. as cited in Spalding 2000, p. 40) estimated that the range of southern mountain caribou has declined by approximately 60 percent, when considering both the Canadian and U.S. range of the population. However, because there are no reliable historical estimates of the number of southern mountain caribou and their distribution (Spalding 2000, p. 34), it is difficult to precisely estimate their historical range for a comparison to their current range. Nevertheless, according to COSEWIC (2014, p. 14), mountain caribou were much more widely distributed than they are today, and thus the range of this population is decreasing. Further evidence of this decline is supported by population surveys. For example, Hatter et al. (2004, p. 7) reported there were an estimated 2,554 individuals in the population in 1995, but in 2014, COSEWIC (2014, p. xvii) estimated the number of caribou in this population has declined to only 1,356 individuals.

Loss of the southern mountain caribou population would result in the loss of the southern-most extent of the range of woodland caribou by about 2.5 degrees of latitude. The Service has not established a threshold of degrees latitude loss or percent range reduction for determining significance to a particular taxon. The importance of specific degrees latitude loss and/or percent range reduction, and the analysis of what such loss or reduction ultimately means to conservation of individual species/subspecies necessarily will be specific to the biology of the species/subspecies in question. However, the extirpation of peripheral populations, such as the southern mountain caribou population, is concerning because of the potential conservation value that peripheral populations can provide to a species or subspecies. Specifically, peripheral populations can possess slight genetic or phenotypic divergences from core populations (Lesica and Allendorf 1995, p. 756; Fraser 2000, p. 50). The genotypic and phenotypic characteristics peripheral populations may provide to the core population of the species may be central to the species' survival in the face of environmental change (Lesica and Allendorf 1995, p. 756; Bunnell et al. 2004, p. 2,242). Additionally, data tend to show that peripheral populations are persistent when species' range collapse occurs (Lomolino and Channell 1995, p. 342; Channell and Lomolino 2000, pp. 84-86; Channell 2004, p. 1). Of 96 species whose last remnant populations were found either in core or periphery of the historical range (rather than some in both core and periphery), 91 (95 percent) of the species were found to exist only in the periphery, and 5 (5 percent) existed solely in the center (Channell and Lomolino 2000, p. 85). Also, as described previously, caribou within the southern mountain population occur at the southern edge of woodland caribou range (i.e., they are a peripheral population), and have adapted to an environment unique to woodland caribou. Peripheral populations adapted to different environments may facilitate speciation (Mayr 1970 in Channell 2004, p. 9). Thus, the available scientific literature data support the importance of peripheral populations for conservation (Fraser 2000, entire; Lesica and Allendorf, 1995, entire).

Additionally, loss of the southern mountain caribou population would result in the loss of the only remaining population of the woodland caribou in the coterminous United States. An additional consequence of the loss of the southern mountain caribou population would be the elimination of the only North American caribou population with the distinct behavior of feeding exclusively on arboreal lichens for 3 or more months of the year. This feeding behavior is related to their spending winter months in high-elevation, steep, mountainous habitats with deep snowpack.

Finally, extirpation of this population segment would result in the loss of a peripheral population segment of woodland caribou that live in, and are behaviorally adapted to, a unique ecological setting characterized by high-elevation, high-precipitation (including deep snowpack), and steep old-growth conifer forests that support abundant arboreal lichens.

V. Significance Conclusion

We conclude that the southern mountain caribou persists in an ecological setting unusual or unique for the subspecies of woodland caribou, and that loss of the southern mountain caribou would result in a significant gap in the range of the woodland caribou subspecies. Therefore, the discrete southern mountain caribou population of woodland caribou that occur in southern British Columbia and in northeastern Washington and northern Idaho meets significance criteria under our DPS policy.

Listable Entity Determination

In conclusion, the Service finds that the southern mountain caribou population meets both the discreteness and significance elements of our DPS policy. It qualifies as discrete because of its marked physical (geographic) and behavioral separation from other populations of the woodland caribou subspecies. It qualifies as significant because of its existence in a unique ecological setting, and because the loss of this population would leave a significant gap in the range of the woodland caribou subspecies. For consistency, we will refer to the southern mountain DU, described by COSEWIC, as the southern mountain caribou DPS. See Figure 1 for a map of the known distribution of subpopulations within the southern mountain caribou DPS.

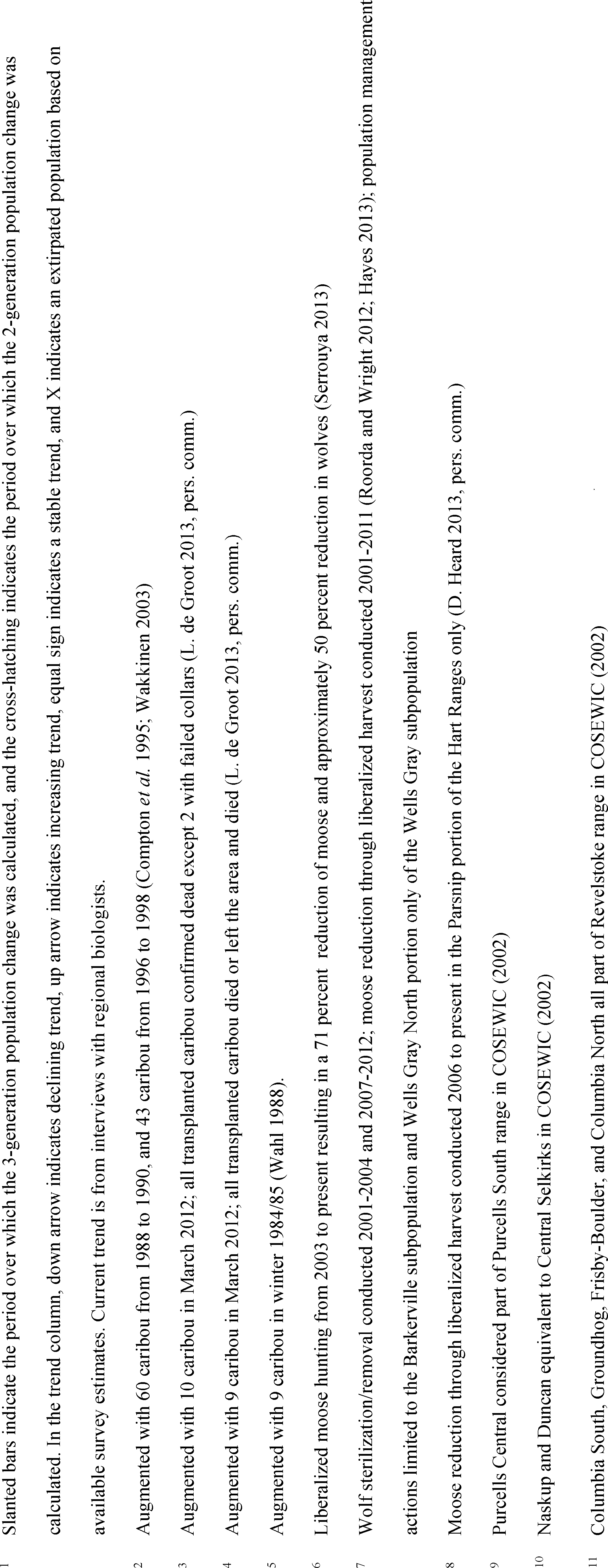

Status of the Southern Mountain Caribou DPS

As described previously, because there are no reliable historical estimates of the number of southern mountain caribou and their distribution (Spalding 2000, p. 34), it is difficult to precisely estimate their historical range for a comparison to their current range. Nevertheless, according to COSEWIC (2014, p. 14), mountain caribou were much more widely distributed than they are today, and thus the range of this population is decreasing. Further evidence of this decline is supported by population surveys. For example, surveys of the southern mountain caribou population in 1995 estimated there were 2,554 individuals in the population (Hatter et al. 2004, p. 7), but in 2014, COSEWIC estimated the number of caribou in this population has declined to only 1,356 individuals (COSWEIC 2014, p. xvii). The status (increasing, declining) of each subpopulation and current population estimate is identified in Table 1.

Currently the southern mountain caribou DPS is composed of 17 subpopulations (15 extant, 2 extirpated) (Figure 1, above). However, Canada has, over time, grouped its caribou populations in accordance with various assessments (COSEWIC 2002, entire; COSEWIC 2011, entire), which has resulted in shifting boundaries, and moving one or more subpopulations between differing geographic groupings of populations. In addition to altering boundaries between populations, some subpopulation boundaries within the populations have changed as well (e.g., some subpopulations have been combined). Thus, the number of subpopulations within the populations has changed. For example, the Allan Creek subpopulation listed in Hatter (2006, in litt.) was grouped with the Wells Gray subpopulation in COSEWIC (2014), and the Kinbasket-South subpopulation listed in Hatter (2006, in litt.) was renamed to Central Rockies subpopulation in COSEWIC (2014) (Ray 2014, pers. comm.). Additionally, the north and south Wells Gray subpopulations referred to in COSEWIC (2002, p. 92) were combined into a single Wells Gray subpopulation in COSEWIC's 2011 Designatable Unit Report (COSEWIC 2011, p. 89). However, the number (17) of subpopulations (which includes 15 extant and 2 recently extirpated subpopulations) and their names encompassed within the southern mountain caribou DPS conforms to Canada's southern mountain (DU9) as identified pursuant to COSEWIC (2011, entire).

All 15 extant subpopulations consist of fewer than 400 individuals each, 13 of which have fewer than 250 individuals, and 9 of which have fewer than 50 individuals (COSEWIC 2014, p. xviii). Fourteen of the 15 extant subpopulations within this DPS have declined since the last assessment by COSEWIC in 2002 (COSEWIC 2014, p. vii). Based on COSEWIC (2014, p. vii), which is new information received after we published our proposed amended listing rule (79 FR 26504; May 8, 2014), the population has declined by at least 45 percent over the last 27 years (3 generations), 40 percent over the last 18 years (2 generations), and 27 percent since the last assessment by COSEWIC in 2002 (roughly 1.4 generations) (COSEWIC 2014, p. vii). These subpopulations are continuing to suffer declines in numbers and range and have become increasingly isolated. Only one subpopulation has increased in numbers (likely due to aggressive wolf control and management) but still consists of fewer than 100 individuals; the most recent estimate was 78 individuals (COSEWIC 2014, p. 43). Given the data cited above, the rate of population decline is accelerating. The accelerated rate of population decline is supported by Wittmer et al. (2005b, p. 265), who studied rates and causes of southern mountain caribou population declines from 1984 to 2002 and found an increasing rate of decline.

Because subpopulation names and boundaries have changed over time, it is difficult to precisely compare subpopulation estimates for some subpopulations within the southern mountain caribou DPS over time. However, according to Wittmer et al. (2005b, p. 413), individual subpopulations have decreased by up to 18 percent per year (Wittmer et al. 2005b, p. 413). For example, the Purcells South subpopulation, which is located above the Montana border, had an estimated 100 individuals in 1982, and only 20 in 2002. According to COSEWIC, this subpopulation had increased to 22 individuals in 2014 (COSEWIC 2104, p. xviii). Even though this subpopulation has slightly increased, it remains depressed.

Additionally, our May 8, 2014, proposed rule (79 FR 26504) stated that the Wells Gray South subpopulation was considered stable at 325 to 350 caribou from 1995 to 2002 (see 79 FR 26514). These numbers were obtained from Hatter et al. (2004, p. 7). However, according to COSEWIC's 2002 status report the subpopulation was estimated at 315 individuals and considered to be in decline (COSEWIC 2002, p. 92). Furthermore, as noted previously, COSEWIC has combined the north and south Wells Gray subpopulations (COSEWIC 2011, p. 89). According to COSEWIC, in 2002, the Wells Gray North subpopulation was estimated at 200 individuals and considered stable. Thus, the COSEWIC (2002) estimate for the combined Wells Gray subpopulation (i.e., north and south subpopulations) was 515 individuals (COSEWIC 2002, p. 92). According to COSEWIC's latest assessment, the Wells Gray subpopulation is estimated at 341 individuals and considered to be declining (COSEWIC 2014, p. 41). Also, in our May 8, 2014, proposed rule (79 FR 26504), we stated that subpopulations in the northern-most portion of the DPS's range were stable (principally the Hart Ranges subpopulation with an estimated 500 individuals in 2005) (see 79 FR 26515). However, according to COSEWIC's latest status assessment, both the Hart Ranges and North Caribou Mountains subpopulations, which are both located at the northern end of this DPS's range, are declining, with population estimates of 398 and 202 caribou, respectively (COSEWIC 2014, p. 41).

Surveys of the subpopulations in the southern mountain caribou DPS estimated that, in 1995, the entire population was approximately 2,554 individuals (Hatter et al. 2004, p. 7). By 2002, this number had decreased to approximately 1,900 individuals (Hatter et al. 2004, p. 7). Currently, the population is estimated to be 1,356 individuals (COSEWIC 2014, p. xvii). Many subpopulations within the southern mountain caribou DPS are reported to have experienced declines of 50 percent or greater between 1995 and 2002 (MCST 2005, p. 1). Some of the most extreme decreases were observed in the Central Selkirk and Purcells South subpopulations. These subpopulations experienced 61 and 78 percent reductions in their populations, respectively, during this time (Harding 2008, p. 3).

Population models indicate declines will continue into the future for the entire southern mountain caribou DPS and for many subpopulations. Hatter et al. (2004, p. 9) predicted subpopulation levels within this DPS under three different scenarios: “optimistic,” “most likely,” and “pessimistic.” Under these scenarios population levels were modeled to decline from the estimated population of 1,905 caribou in 2002 to 1,534 (optimistic), 1,169 (most likely), or 820 (pessimistic), by 2022. The most recent population estimate of 1,356 caribou (COSEWIC 2014, p. 41) is already well below Hatter et al.' s (2004, p. 9) predicted population estimate of 1,534 caribou in 2022 projected under the optimistic scenario. In addition, all three scenarios reported the extirpation of two (optimistic), three (most likely), or five (pessimistic) subpopulations by 2022 (Hatter et al. 2004, p. 9). As of 2014, George Mountain and Purcells Central, two of the subpopulations within the southern mountain caribou DPS, are now considered to be extirpated (COSEWIC 2014, p. 16).

According to Hatter et al. (2004, pp. 9, 11), no models predicted extinction of the woodland caribou population within the DPS in the next 100 years (Hatter et al. 2004, p. 11). However, reductions in the size of the entire population were predicted. Using the same scenarios from Hatter et al. (2004) as described above (“optimistic,” “most likely,” and “pessimistic”), the average time until the population of woodland caribou within the southern mountain caribou DPS is fewer than 1,000 individuals was projected to be 100, 84, and 26 years, respectively (Hatter et al. 2004, p. 11). These estimates do not account for the relationship between density and adult female survival, and may be a conservative estimate of time to extinction (in other words, may underestimate the timeframes). Wittmer (2004, p. 88) attempted to account for density-dependent adult female survival and predicted extinction of all subpopulations in the DPS within the next 100 years. More recent population viability analyses (PVAs) have predicted quasi-extinction or extinction of several of the subpopulations within the DPS. A PVA conducted by Hatter (2006, p. 7, in litt.) predicted that the probability of quasi-extinction (a number below which extinction is very likely due to genetic or demographic risks, considered to be fewer than 20 animals in this case) in 20 years was 100 percent for 6 of the 15 subpopulations, greater than 50 percent for 11 of the 15 subpopulations, and greater than 20 percent for 12 of the 15 subpopulations within the DPS. Hatter (2006, p. 7, in litt.) also predicted quasi-extinction of another subpopulation (Wells Gray) in 87 years. Thus, a total of 13 of the 15 subpopulations could be quasi-extinct within 90 years, leaving only 2 subpopulations (Hart Ranges and North Caribou Mountains) remaining at the extreme northern portion of the DPS's range. Both the Hart Ranges and North Caribou Mountains subpopulations are declining (COSEWIC 2014, p. 41). These two subpopulations are subjected to the same threats acting on the other subpopulations in this DPS (COSEWIC 2014, p. 56), and are thus at a greater risk of extirpation than what we understood at the time of our May 8, 2014, proposed rule (79 FR 26504).

Wittmer et al. (2010, entire) conducted a PVA on 10 of the subpopulations assessed by Hatter (2006, entire, in litt.). All 10 subpopulations were predicted to decline to extinction within 200 years when models incorporated the declines in adult female survival known to occur with increasing proportions of young forest and declining population densities (Wittmer et al. 2010, p. 86). The results of PVA modeling by Wittmer et al. (2010, p. 90) also suggested that 7 of the 10 populations have a greater than 90 percent cumulative probability of extirpation within 100 years. Further, Wittmer et al. (2010, p. 91) suggested that as subpopulation densities decline, predation (see “Predation” under the Factor C analysis, below) may have a disproportionately greater effect, which is defined as depensatory mortality. Thus, the length of time to extirpation may be less than the timeframes suggested by PVA modeling that does not account for depensatory mortality. Therefore, the 200 and 100 year time spans that Wittmer et al. (2010, pp. 86, 90) predict for extirpation of all 10 and 7 of the 10 subpopulations, respectively, may be an overestimate (i.e., extirpation of these subpopulations may occur in less time).

Along with these documented and predicted population declines, subpopulations of woodland caribou within the DPS are becoming increasingly fragmented and isolated (Wittmer 2004, p. 28; van Oort et al. 2011, p. 25; Serrouya et al. 2012, p. 2,598). Fragmentation and isolation are particularly pronounced in the southern portion of the southern mountain caribou DPS (Wittmer 2004, p. 28). In fact, neither Wittmer et al. (2005b, p. 409) nor van Oort et al. (2011, p. 221) detected movement of individuals between subpopulations in the DPS.

Fragmentation and isolation are likely accelerating the extinction process and reducing the probability of demographic rescue from natural immigration or emigration because mountain caribou appear to lack the inherent behavior to disperse long distances (Van Oort et al. 2011, pp. 215, 221-222). As stated previously, mountain caribou were more widely distributed in mountainous areas of southeastern British Columbia (Canada), northern Idaho, and northeastern Washington. Currently, mountain caribou exist in several discrete subpopulations, which could be considered a metapopulation structure. However, a functioning metapopulation structure requires immigration and emigration between the subpopulations within the metapopulation via dispersal of juveniles (natal dispersal), adults (breeding dispersal), or both. Dispersal of individuals (natal or breeding) can facilitate demographic rescue of neighboring populations that are in decline or recolonization of ranges from which populations have been extirpated (i.e., classic metapopulation theory). Species whose historical distribution was more widely and evenly distributed (such as mountain caribou) (van Oort et al. 2011, p. 221) that have been fragmented into subpopulations via habitat fragmentation and loss may appear to exist in a metapopulation structure when in fact, because they may not have evolved the innate behavior to disperse among subpopulations, their fragmented distribution may actually represent a geographic pattern of extinction (van Oort et al. 2011, p. 215). Also, as excerpted from COSEWIC (2014, p. 43):

Rescue effect from natural dispersal is unlikely for the southern mountain DU. The nearest subpopulation in the United States is the South Selkirk subpopulation, which is shared between [British Columbia], Idaho, and Washington, and currently consists of only 28 mature individuals. Even within the southern mountain DU, subpopulations are effectively isolated from one another with almost no evidence of movement between them except at the northern extent of the DU (van Oort et al. 2011). The closest DU is the Central Mountain and Northern Mountain DU, but these animals are not only declining in most neighboring subpopulations but are adapted to living in shallow snow environments and will likely encounter difficulty adjusting to deep snow conditions. The same characteristics that render all three mountain caribou DUs as discrete and significant relative to neighboring caribou subpopulations (see Designatable Units; COSEWIC 2011) make the prospects for rescue highly unlikely.

Finally, COSEWIC recommended that the southern mountain DU be listed as endangered under SARA (COSEWIC 2014, pp. iv, xix). Endangered is defined by SARA as a wildlife species that is facing imminent extirpation or extinction. COSEWIC cited similar reasons as the threats we identified in this final rule including, but not limited to: Small, declining, and isolated subpopulations; recent extirpation of two subpopulations; recent PVA modeling predicting further declines and extirpation of subpopulations; and continuing and escalating threats (COSEWIC 2014, pp. iv, vii). The International Union for the Conservation of Nature-Conservation Measures Partnership (IUCN-CMP) threat assessment for the southern mountain DU concluded that the threat impact is the maximum (Very High) based on the unified threats classification system (Master et al. 2009, entire), which indicates continued serious declines are anticipated (COSEWIC 2014, pp. 109-113).

Summary of Factors Affecting the Species

Section 4 of the Act (16 U.S.C. 1533), and its implementing regulations at 50 CFR part 424, set forth the procedures for adding species to the Federal Lists of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants. Under section 4(a)(1) of the Act, we determine whether a species is an endangered species or threatened species because of any one or a combination of the following: (A) The present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range; (B) overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes; (C) disease or predation; (D) the inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; and (E) other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence. Listing actions may be warranted because of any of the above threat factors, singly or in combination. We discuss each of these factors for the southern mountain caribou DPS below.

A. The Present or Threatened Destruction, Modification, or Curtailment of Its Habitat or Range

Threats to caribou habitat within the southern mountain DPS include forest harvest, human development, recreation, and effects due to climate change (such as an increase in fires and a significant decrease in alpine habitats, which is loosely correlated with the distribution of the arboreal lichens on which these caribou depend). In addition to causing direct impacts, these threats often catalyze indirect impacts to caribou, including, but not limited to, predation, increased physiological stress, and displacement from important habitats. Both direct and indirect impacts to caribou from habitat destruction, modification, and curtailment are described below.

Historically, the caribou subpopulations that make up the southern mountain caribou DPS were distributed throughout the western Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, northern Idaho, and northeastern Washington (Apps and McLellan 2006, p. 84). As previously discussed, caribou within the southern mountain caribou DPS are strongly associated with high-elevation, high-precipitation, old-growth forested landscapes (Stevenson et al. 2001, pp. 3-5; Cichowski et al. 2004, pp. 224, 231; Apps and McLellan 2006, pp. 84, 91; COSEWIC 2011, p. 50) that support their uniquely exclusive winter diet of arboreal lichens (Cichowski et al. 2004, p. 229).

It is estimated that about 98 percent of the caribou in the southern mountain caribou DPS rely on arboreal lichens as their primary winter food. They have adapted to the high-elevation, deep-snow habitat that occurs within this area of British Columbia, northern Idaho, and northeastern Washington (Apps and McLellan 2006, p. 84). The present distribution of woodland caribou in Canada is much reduced from historical accounts, with reports indicating that the extent of occurrence in British Columbia and Ontario populations has decreased by up to 40 percent in the last few centuries (COSEWIC 2002, pp. viii, 30). According to Spalding (2000, p. 40) the entire range of southern mountain caribou has decreased by 60 percent when including both the United States and Canadian portion of the population's historical range. The greatest reduction has occurred in subpopulations comprising the southern mountain caribou DPS (COSEWIC 2002, p. 30; COSEWIC 2011, p. 49). Hunting was historically considered the main cause of range contraction in the central and southern portions of British Columbia. However, predation, habitat fragmentation from forestry operations, and human development are now considered the main concerns (COSEWIC 2002, p. 30).

Forest Harvest

Forestry has been the dominant land use within the range of the southern mountain caribou DPS in British Columbia throughout the 20th century. The majority of timber harvesting has occurred since the late 1960s (Stevenson et al. 2001, pp. 9-10). Prior to 1966 and before pulp mills were built in the interior of British Columbia, a variety of forest harvesting systems were utilized, targeting primarily spruce and Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) sawlogs, and pole-sized western red cedar. It was not until after 1966, when market conditions changed to meet the demand for pulp and other timber products, that the majority of timber harvesting occurred through clear-cutting large blocks of forest (Stevenson et al. 2001, p. 10). However, in the 1970s, some areas in the southern Selkirk Mountains and the North Thompson area (north of Revelstoke, British Columbia) were only partially cut in an effort to maintain habitat for caribou (Stevenson et al. 2001, p. 10). In the 1990s, there was an increase in both experimental and operational partial cutting in caribou habitat. Partial cuts continue to remain a small proportion of total area harvested each year within caribou habitat in British Columbia (Stevenson et al. 2001, p. 10).

Historically, within the U.S. portion of the southern mountain caribou DPS, habitat impacts have been primarily due to logging and fire (Evans 1960, p. 109). In the early 19th century, intensive logging occurred from approximately 1907 through 1922, when the foothills and lowlands were logged upwards in elevation to the present U.S. national forest boundaries (Evans 1960, p. 110). Partly because of this logging, farmlands replaced moister valleys that once resembled the rain forests of the Pacific coast (Evans 1960, p. 111). From the 1920s through 1960, logging continued into caribou habitat on the Kanisku National Forest in Idaho (now the Idaho Panhandle National Forest) (Evans 1960, pp. 118-120). In addition, insect and disease outbreaks affected large areas of white pine (Pinus strobus) stands in caribou habitat, and Engelmann spruce habitat was heavily affected by windstorms, insect outbreaks, and subsequent salvage logging (Evans 1960, pp. 123-124). As a result, spruce became the center of importance in the lumber industry of this region. This led to further harvest of spruce habitat in adjacent, higher elevation drainages previously unaffected by insect outbreaks (Evans 1960, pp. 124-131). It is not known how much forest within the range of the southern mountain caribou DPS has been historically harvested; however, forest harvest likely had and continues to have direct and indirect impacts on caribou and their habitat, contributing to the curtailment and modification of the habitat of the southern mountain caribou DPS.

Harvesting of forests has both direct and indirect effects on caribou habitat within the southern mountain caribou DPS. A direct effect of forest harvest is loss of large expanses of contiguous old-growth forest habitats. Caribou in the southern mountain caribou DPS rely upon these habitats as an important means of limiting the effect of predation. Their strategy is to spread over large areas at high elevation that other prey species avoid (Seip and Cichowski 1996, p. 79; MCTAC 2002, pp. 20-21). These old-growth forests have evolved with few and small-scale natural disturbances such as wildfires, insects, or diseases. When these disturbances did occur, they created only small and natural gaps in the forest canopy that allowed trees to regenerate and grow (Seip 1998, pp. 204-205). Forest harvesting through large-scale clear-cutting creates additional and larger openings in old-growth forest habitat. These openings allow for additional growth of early seral habitat.

Research of woodland caribou has shown that caribou alter their movement patterns to avoid areas of disturbance where forest harvest has occurred (Smith et al. 2000, p. 1435; Courtois et al. 2007, p. 496). With less contiguous old-growth habitat, caribou are also limited to increasingly fewer places on the landscape. Further, woodland caribou that do remain in harvested areas have been documented to have decreased survival due to predation vulnerability (Courtois et al. 2007, p. 496). This is because the early seral habitat, which establishes itself in recently harvested or disturbed areas, also attracts other ungulate species such as deer, elk, and moose to areas that were previously unsuitable for these species (MCST 2005, pp. 4-5; Bowman et al. 2010, p. 464). With the increase in the distribution and abundance of prey species in or near habitats located where caribou occur comes an increase in predators and therefore an increase in predation on caribou. Predation has been reported as one of the most important direct causes of population decline for caribou in the southern mountain caribou DPS (see also C. Disease or Predation, below; MCST 2005, p. 4; Wittmer et al. 2005a, p. 257; Wittmer et al. 2005b, p. 417; Wittmer et al. 2007, p. 576).

Roads created to support forest harvest activities have also fragmented habitat. Roads create linear features that provide easy travel corridors for predators into and through difficult habitats where caribou seek refuge from predators (MCST 2005, p. 5; Wittmer et al. 2007, p. 576). It has been estimated that forest roads throughout British Columbia (which includes the southern mountain caribou DPS) expanded by 4,100 percent (from 528 to 21,748 mi (850 to 35,000 km)) between 1950 and 1990, and most of these roads were associated with forest harvesting (Stevenson et al. 2001, p. 10). In the United States, roads associated with logging and forest administration developed continuously from 1900 through 1960. These roads allowed logging in new areas and upper-elevation drainages (Evans 1960, pp. 123-124). In both Canada and the United States, these roads have also generated more human activity and human disturbance in habitat that was previously less accessible to humans (MCST 2005, p. 5). See E. Other Natural or Manmade Factors Affecting Its Continued Existence for additional discussion.

The harvest of late-successional (old-growth) forests directly affects availability of arboreal lichens, the primary winter food item for caribou within the southern mountain caribou DPS. Caribou within this area rely on arboreal lichens for winter forage for 3 or more months of the year (Apps et al. 2001, p. 65; Stevenson et al. 2001, p. 1; MCST 2005, p. 2). In recent decades, however, local caribou populations in the southern mountain caribou DPS have declined faster than mature forests have been harvested. This suggests that arboreal lichens are not the limiting factor for woodland caribou in this area (MCST 2005, p. 4; Wittmer et al. 2005a, p. 265; Wittmer et al. 2007, p. 576).

Forest Fires