AGENCY:

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

ACTION:

Notice of proposed rulemaking.

SUMMARY:

The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Board) is inviting comment on a proposal to establish risk-based capital requirements for depository institution holding companies that are significantly engaged in insurance activities. The Board is proposing a risk-based capital framework, termed the Building Block Approach, that adjusts and aggregates existing legal entity capital requirements to determine an enterprise-wide capital requirement, together with a risk-based capital requirement excluding insurance activities, in compliance with section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Act. The Board is additionally proposing to apply a buffer to limit an insurance depository institution holding company's capital distributions and discretionary bonus payments if it does not hold sufficient capital relative to enterprise-wide risk, including risk from insurance activities. The proposal would also revise reporting requirements for depository institution holding companies significantly engaged in insurance activities.

DATES:

Comments must be received on or before December 23, 2019.

ADDRESSES:

You may submit comments, identified by Docket No. R-1673 and RIN 7100-AF 56, by any of the following methods:

- Agency website: http://www.federalreserve.gov. Follow the instructions for submitting comments at http://www.federalreserve.gov/generalinfo/foia/ProposedRegs.cfm.

- Email: regs.comments@federalreserve.gov. Include docket number in the subject line of the message.

- Fax: (202) 452-3819 or (202) 452-3102.

- Mail: Ann E. Misback, Secretary, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 20th Street and Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20551.

All public comments are available from the Board's website at http://www.federalreserve.gov/generalinfo/foia/ProposedRegs.cfm as submitted, unless modified for technical reasons or to remove sensitive personal identifying information at the commenter's request. Accordingly, comments will not be edited to remove any identifying or contact information. Public comments may also be viewed electronically or in paper form in Room 146, 1709 New York Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20006, between 9:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. on weekdays.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Thomas Sullivan, Associate Director, (202) 475-7656; Linda Duzick, Manager, (202) 728-5881; Matti Peltonen, Supervisory Insurance Valuation Analyst, (202) 872-7587; Brad Roberts, Supervisory Insurance Valuation Analyst, (202) 452-2204; or Matthew Walker, Supervisory Insurance Valuation Analyst, (202) 872-4971; Division of Supervision and Regulation; or Laurie Schaffer, Associate General Counsel, (202) 452-2272; David Alexander, Senior Counsel, (202) 452-2877; Andrew Hartlage, Counsel, (202) 452-6483; or Jonah Kind, Senior Attorney, (202) 452-2045; Legal Division, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 20th and C Streets NW, Washington, DC 20551. For the hearing impaired only, Telecommunication Device for the Deaf, (202) 263-4869.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Table of Contents

I. Introduction

II. Background

A. The Dodd-Frank Act and Capital Requirements for Insurance Depository Institution Holding Companies

B. The 2016 Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking on Capital Requirements for Supervised Institutions Significantly Engaged in Insurance Activities

C. General Comments on the ANPR

D. Comments on Particular Aspects of the ANPR

1. Threshold for Determining a Firm to be Subject to the BBA

2. Grouping of Companies in the BBA

3. Treatment of Non Insurance, Non Banking Companies

4. Adjustments

5. Scalars

6. Available Capital

III. The Proposal

A. Overview of the BBA

B. Dodd-Frank Act Capital Calculation

IV. The Building Block Approach

A. Structure of the BBA

B. Covered Institutions and Scope of the BBA

C. Identification of Building Blocks and Building Block Parents

1. Inventory

2. Applicable Capital Framework

3. Building Block Parents

(a) Capital-Regulated Companies and Material Financial Entities as Building Block Parents

(b) Other Instances of Building Block Parents

D. Aggregation in the BBA

V. Scaling Under the BBA

A. Key Considerations in Evaluating Scaling Mechanisms

B. Identification of Jurisdictions and Frameworks Where Scalars Are Needed

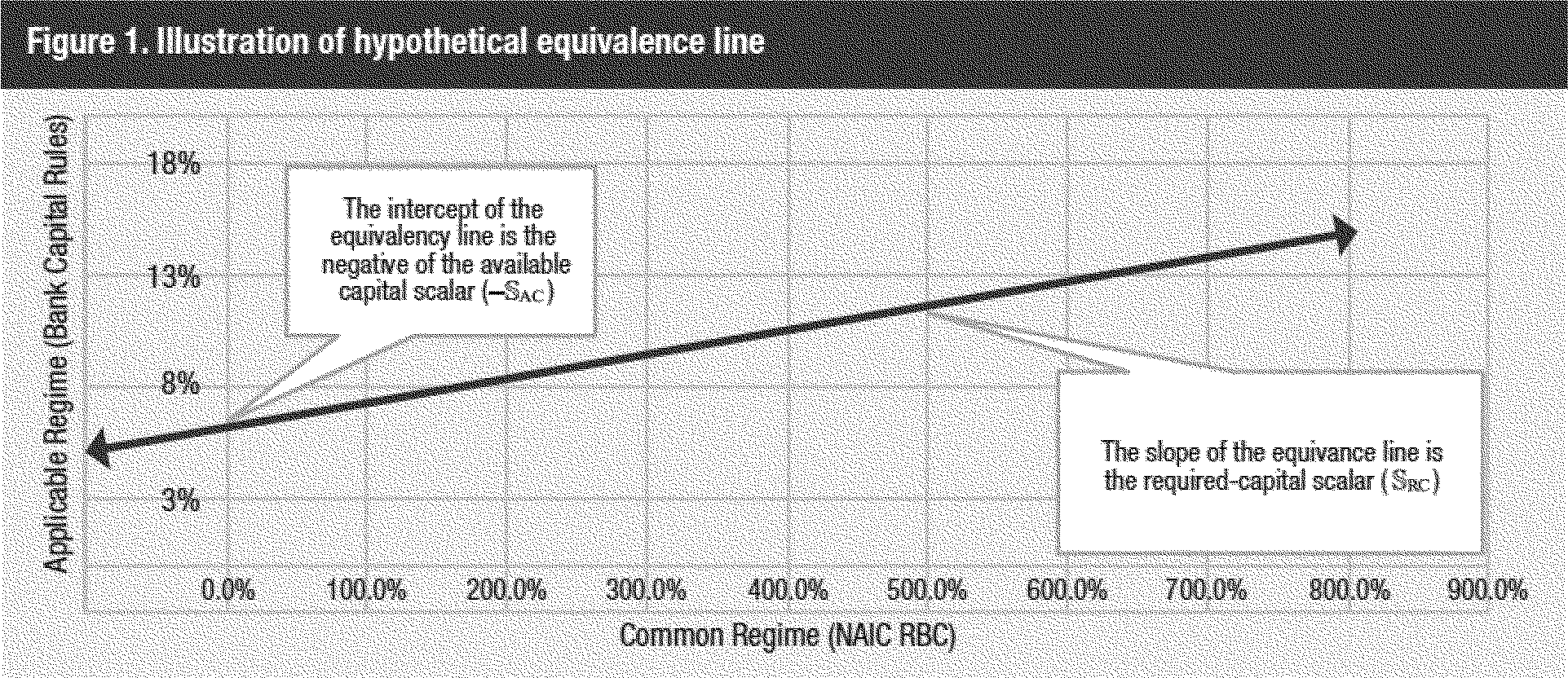

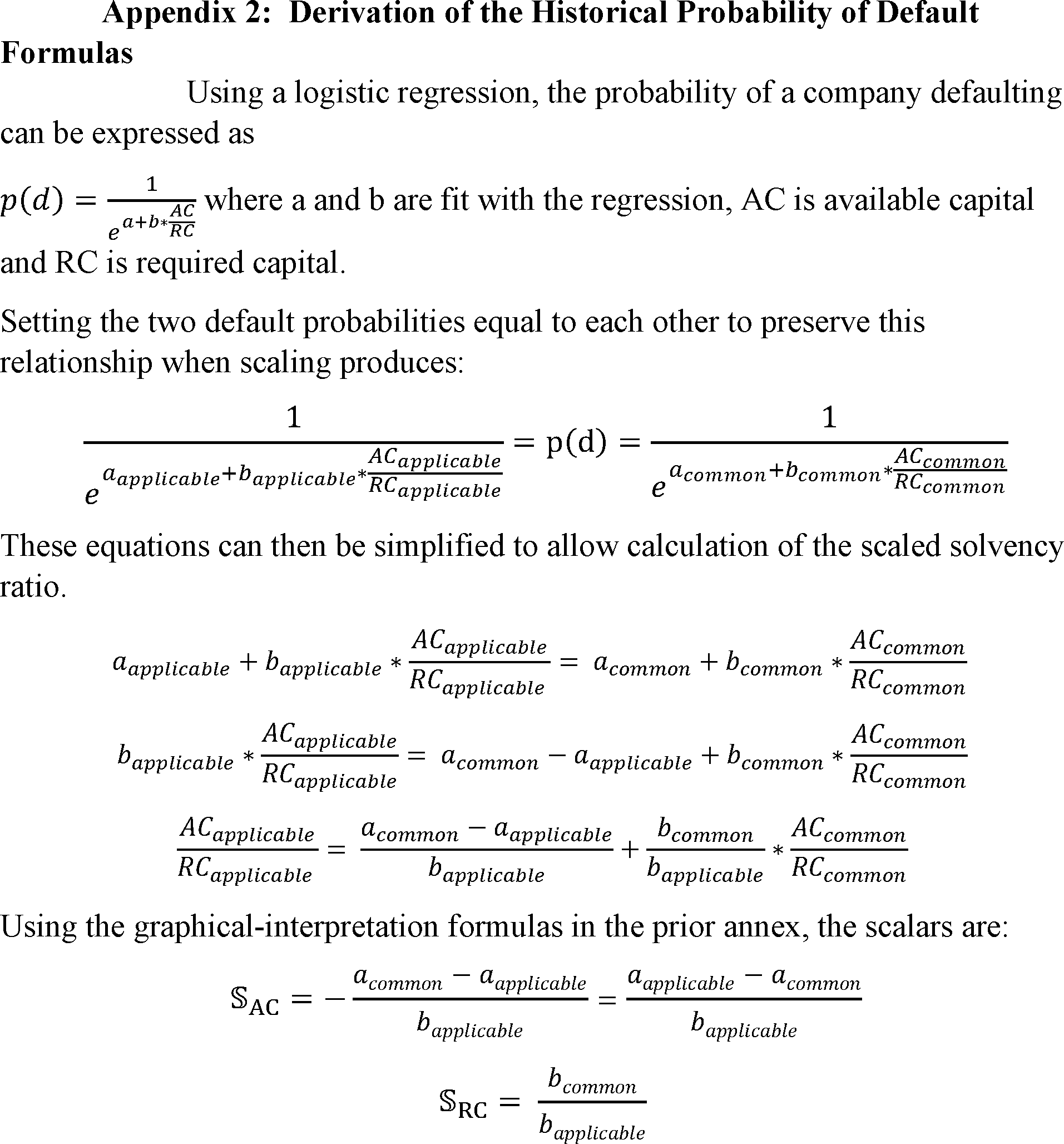

C. The BBA's Approach to Determining Scalars

D. Approach Where Scalars Are Not Specified

VI. Determination of Capital Requirements Under the BBA

A. Capital Requirement for a Building Block

B. Regulatory Adjustments to Building Block Capital Requirements

1. Adjusting Capital Requirements for Permitted and Prescribed Accounting Practices Under State Laws

2. Certain Intercompany Transactions

3. Adjusting Capital Requirements for Transitional Measures in Applicable Capital Frameworks

4. Risks of Certain Intermediary Companies

5. Risks Relating to Title Insurance

C. Scaling and Aggregating Building Blocks' Adjusted Capital Requirements

VII. Determination of Available Capital Under the BBA

A. Approach to Determining Available Capital

1. Key Considerations in Determining Available Capital

2. Aggregation of Building Blocks' Available Capital

B. Regulatory Adjustments and Deductions to Building Block Available Capital

1. Criteria for Qualifying Capital Instruments

2. BBA Treatment of Deduction of Insurance Underwriting Risk Capital

3. Adjusting Available Capital for Permitted and Prescribed Practices under State Laws

4. Adjusting Available Capital for Transitional Measures in Applicable Capital Frameworks

5. Deduction of Investments in Own Capital Instruments

6. Reciprocal Cross Holdings in Capital of Financial Institutions

C. Limit on Certain Capital Instruments in Available Capital Under the BBA

D. Board Approval of Capital Elements

VIII. The BBA Ratio, Minimum Capital Requirement and Capital Conservation Buffer

A. The BBA Ratio and Proposed Minimum Requirement

B. Proposed Capital Conservation Buffer

IX. Sample BBA Calculation

A. Inventory

B. Applicable Capital Frameworks

C. Identification of Building Block Parents and Building Blocks

D. Identification of Available Capital and Capital Requirements under Applicable Capital Frameworks

E. Adjustments to Available Capital and Capital Requirements

1. Illustration of Adjustments to Capital Requirements

2. Illustration of Adjustments to Available Capital

F. Scaling Adjusted Available Capital and Capital Requirements

G. Roll Up and Aggregation of Building Blocks

H. Calculation of BBA Ratio and Application of Minimum Requirement and Buffer

X. Reporting Form and Disclosure Requirements

XI. Impact Assessment of Proposed Rule

A. Analysis of Potential Benefits

1. A Capital Requirement for the Board's Consolidated Supervision

2. Going Concern Safety and Soundness of the Supervised Institution

3. Protection of the Subsidiary Insured Depository Institution

4. Improved Efficiencies Resulting from Better Capital Management

5. Fulfillment of a Statutory Requirement

B. Analysis of Potential Costs

1. Initial and Ongoing Costs to Comply

2. Review of Impacts Resulting from the BBA

3. Impact on Premiums and Fees

4. Impact on Financial Intermediation

C. Assessment of Benefits and Costs

XII. Administrative Law Matters

A. Solicitation of Comments on the Use of Plain Language

B. Paperwork Reduction Act

C. Regulatory Flexibility Act

List of Subjects

PART 217—CAPITAL ADEQUACY OF BANK HOLDING COMPANIES, SAVINGS AND LOAN HOLDING COMPANIES, AND STATE MEMBER BANKS (REGULATION Q)

Subpart A—General Provisions

§ 217.1 Purpose, applicability, reservations of authority, and timing.

§ 217.2 Definitions.

Subpart B—Capital Ratio Requirements and Buffers

§ 217.10 Minimum capital requirements.

§ 217.11 Capital conservation buffer, countercyclical capital buffer amount, and GSIB surcharge.

Subpart J—Capital Requirements for Board-regulated Institutions Significantly Engaged in Insurance Activities

§ 217.601 Purpose, applicability, reservations of authority, and scope

§ 217.602 Definitions: Capital Requirements

§ 217.603 BBA Ratio and Minimum Requirements

§ 217.604 Capital Conservation Buffer

§ 217.605 Determination of Building Blocks

§ 217.606 Scaling Parameters Aggregation of Building Blocks' Capital Requirement and Available Capital

§ 217.607 Capital Requirements under the Building Block Approach

§ 217.608 Available Capital Resources under the Building Block Approach

PART 252—ENHANCED PRUDENTIAL STANDARDS (REGULATION YY)

Subpart B—Company-Run Stress Test Requirements for Certain U.S. Banking Organizations with Total Consolidated Assets over $10 Billion and Less Than $50 Billion

I. Introduction

The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Board) is issuing this notice of proposed rulemaking (NPR) to seek comment on a proposal to establish risk-based capital requirements for certain depository institution holding companies significantly engaged in insurance activities (insurance depository institution holding companies).[1] As discussed in further detail in the description of the proposal, insurance depository institution holding companies include depository institution holding companies that are insurance underwriters, and depository institution holding companies that hold a significant percentage of total assets in insurance underwriting subsidiaries. The proposal introduces an enterprise-wide risk-based capital framework, termed the “building block” approach (BBA), that incorporates legal entity capital requirements such as the requirements prescribed by state insurance regulators, taking into account differences between the business of insurance and banking. The Board proposes to establish an enterprise-wide capital requirement for insurance depository institution holding companies based on the BBA framework, and, separately, to apply a minimum risk-based capital requirement to the enterprise using the flexibility afforded under recent amendments to section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act) to exclude certain state and foreign regulated insurance operations.[2] The Board is also proposing to apply a buffer that limits an insurance depository institution holding company's capital distributions and discretionary bonus payments if it does not hold sufficient capital relative to enterprise-wide risk, including risk from insurance activities. The minimum risk-based capital requirement is proposed pursuant to the Board's authority under section 10 of the Home Owners' Loan Act (HOLA) [3] and section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Act.[4]

II. Background

A. The Dodd-Frank Act and Capital Requirements for Insurance Depository Institution Holding Companies

In response to the 2007-09 financial crisis, Congress enacted the Dodd-Frank Act, which, among other objectives, was enacted to ensure fair and appropriate supervision of depository institutions without regard to the size or type of charter and streamline the supervision of depository institutions (DIs) and their holding companies. In furtherance of these objectives, Title III of the Dodd-Frank Act expanded the Board's supervisory role beyond bank holding companies (BHCs) by transferring to the Board all supervisory functions related to savings and loan holding companies (SLHCs) and their non-depository subsidiaries. As a result, the Board became the federal supervisory authority for all DI holding companies, including insurance depository institution holding companies.[5] Concurrent with the expansion of the Board's supervisory role, section 616 of the Dodd-Frank Act amended HOLA to provide the Board express authority to adopt regulations or orders that set capital requirements for SLHCs.[6]

Any capital requirements the Board may establish for SLHCs are subject to minimum standards under the Dodd-Frank Act. Specifically, section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Act requires the Board to establish minimum risk-based and leverage capital requirements on a consolidated basis for depository institution holding companies.[7] These requirements must be not less than the capital requirements established by the Federal banking agencies to apply to insured depository institutions (IDIs), nor quantitatively lower than the capital requirements that applied to IDIs when the Dodd-Frank Act was enacted. The Dodd-Frank Act sets a floor for any capital requirements established under section 171 that is based on the capital requirements established by the appropriate Federal banking agencies to apply to insured depository institutions under the prompt corrective action regulations implementing section 38 of the FDI Act.[8]

The Board issued a revised capital rule in 2013, which served to strengthen the capital requirements applicable to banking organizations supervised by the Board by improving both the quality and quantity of regulatory capital and increasing risk-sensitivity. In consideration of requirements of section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Act, in 2012, the Board had sought comment on the proposed application of the revised capital rule to all firms supervised by the Board that are subject to regulatory capital requirements, including all savings and loan holding companies significantly engaged in insurance activities. In response, the Board received comments by or on behalf of supervised firms engaged primarily in insurance activities that requested an exemption from the capital rule in order to recognize differences in their business model compared with those of more traditional banking organizations. After considering these comments, the Board determined to exclude insurance SLHCs from the application of the rule.[9] The Board committed to explore further whether and how the revised capital rule, hereinafter referred to as the “banking capital rule,” should be modified for insurance SLHCs in a manner consistent with section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Act and safety and soundness concerns.

Section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Act was amended in 2014 (2014 Amendment) to provide the Board flexibility when developing consolidated capital requirements for insurance depository institution holding companies.[10] The 2014 Amendment permits the Board to exclude companies engaged in the business of insurance and regulated by a state insurance regulator, as well as certain companies engaged in the business of insurance and regulated by a foreign insurance regulator.

The 2014 Amendment to section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Act does not require the Board to exclude state-regulated, or certain foreign-regulated, insurers from its risk-based capital requirements. The Board has considered that exclusion of these insurers from the measurement and application of all risk-based capital requirements could present challenges to the Board's ability to timely and accurately assess the risk profile and capital adequacy of the entire organization and fulfill the Board's responsibility as a prudential supervisor of the organization. A more effective regulatory capital framework, reflecting the Board's objectives as consolidated supervisor of insurance depository institution holding companies, would capture all risks that face the enterprise and potentially could jeopardize the organization's ability to serve as a source of financial strength to the subsidiary IDI. There is support for taking this approach in both section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Act and section 10 of HOLA.

Section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Act also provides that the Board may not require, under its authority pursuant to section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Act or HOLA, financial statements prepared in accordance with U.S. generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) from a supervised firm that is also a state-regulated insurer and only files financial statements utilizing Statutory Accounting Principles (SAP).[11] The Board notes that, unlike U.S. GAAP, SAP does not include an accounting consolidation concept. As discussed in detail in subsequent sections of this notice, the BBA is thus an aggregation-based approach and the Board's proposal is designed as a comprehensive approach to capturing risk, including all material risks, at the level of the entire enterprise or group.

B. The 2016 Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking on Capital Requirements for Supervised Institutions Significantly Engaged in Insurance Activities

On June 14, 2016, the Board published in the Federal Register an advance notice of proposed rulemaking (ANPR) entitled “Capital Requirements for Supervised Institutions Significantly Engaged in Insurance Activities.” [12] In the ANPR, the Board conceptually described the BBA as a capital framework, contemplated for insurance depository institution holding companies, based on aggregating available capital and capital requirements across the different legal entities in an insurance group to calculate these two amounts at the enterprise level.[13] The ANPR described a number of potential adjustments that could be applied in the BBA, including adjustments to address variations in accounting practices across jurisdictions in which insurers operate, double leverage, aggregation across different jurisdictional capital frameworks, and defining loss-absorbing capital resources.[14] In the ANPR, the Board asked questions on all aspects of the BBA, including key considerations in evaluating capital frameworks for insurance depository institution holding companies, whether the BBA was appropriate for these firms as well as advantages and disadvantages of this approach, and the adjustments contemplated for use in the BBA.[15]

Among other things, the ANPR provided stakeholders with an opportunity to comment on the Board's development of a capital framework for insurance depository institution holding companies at an early stage. This NPR builds upon the discussion in the ANPR and reflects the Board's review of comments submitted in response to the ANPR. The comments are generally addressed below.

C. General Comments on the ANPR

The Board received 27 public comments on the ANPR from interested parties including supervised insurance companies, insurers not supervised by the Board, insurance and other trade associations, regulatory and actuarial associations, and others. Generally, commenters supported the Board's proposed tailoring of a capital requirement that is insurance-centric and appreciated the transparency and early opportunity to provide comment. Commenters agreed that capital frameworks should capture all material companies and risks faced by insurers, reflect on- and off-balance sheet exposures, and build on existing capital frameworks where possible. According to commenters, the Board's capital framework also should be informed by its potential effects on asset allocation decisions of insurers, not unduly incentivizing or disincentivizing allocation to certain asset classes. Commenters generally supported the Board's proposal to efficiently use legal entity capital requirements within an appropriate capital framework for both insurance depository institution holding companies and those insurance firms designated by the FSOC as systemically important. Commenters further suggested that the BBA should be built on principles that include minimal adjustments to already-applicable capital frameworks, indifference as to structure of the supervised firm, comparability across capital frameworks to which the supervised firm's entities are subject, appropriately reflecting insurance and non-insurance frameworks, and transparency. Commenters observed that the BBA would align relatively well with regulators' treatment of capital at individual companies and, consequently, the ways that capital may not be fungible.

In the ANPR, the Board asked what capital requirement should be used for insurance companies, banking companies, and companies not subject to any company-level capital requirement, as used in the BBA. For insurance companies subject to the NAIC's risk-based capital (RBC) requirements, commenters generally supported the use of required capital at the Company Action Level (CAL) under the NAIC RBC framework, with some preferring the use of a greater threshold, often termed the “trend test” level.[16] In commenters' views, a key advantage of the BBA is compatibility with existing legal entity capital requirements. The BBA was also viewed as being reasonably able to capture the risks of non-homogenous products across jurisdictions and varying legal and regulatory environments. Since it is an approach that builds on existing legal entity capital requirements, the BBA would absorb the impact of how those requirements treat the subject entities' products.

According to commenters, among the key disadvantages of the BBA would be that the framework must reconcile possibly divergent valuation and accounting practices. As an aggregated approach, the BBA may not align with the insurance depository institution holding company's own internal approach for risk assessment, which may be conducted on a consolidated basis. Commenters expressed varying views on whether the BBA would be prone to regulatory arbitrage, but many noted that this may not be a shortcoming of the BBA if capital movements are subject to restrictions. With regard to specific implementation issues, commenters noted, among other things, that the BBA may entail challenges in calibrating scalars (the mechanism used to bring divergent capital frameworks to a common basis), identifying scalars with a sufficient level of granularity, and addressing differences in global valuation practices. Furthermore, commenters noted that valuation bases for required capital may differ from valuation bases for available capital.

Some commenters raised concerns about implementation costs and, noting that the BBA as set out may tend to have relatively low impact in terms of costs to regulators and the industry, suggested implementing the BBA over a timeframe in the range of one to two years. Multiple commenters agreed that the BBA is expected to have minimal setup and ongoing maintenance and compliance costs. One commenter noted that since the BBA is a tailored approach that uses a firm's existing books and records without compromising supervisory objectives, the BBA's design is anticipated to aid in controlling the burden.

D. Comments on Particular Aspects of the ANPR

1. Threshold for Determining a Firm To Be Subject to the BBA

The Board sought comment on the criteria that should be used to determine which supervised firms would be subject to the BBA. Commenters generally did not disagree with the Board's proposal to apply the BBA to supervised firms with 25 percent or more of total consolidated assets attributable to insurance underwriting activities (other than assets associated with insurance underwriting for credit risk). One commenter suggested that insurance liabilities, rather than dedicated assets, should be considered the principal indicator of insurance activity. Some comments suggested that the Board should consider a depository institution holding company to be an insurance depository institution holding company subject to the BBA when either the ultimate parent of the enterprise is an operating insurance underwriting company, or, if this is not the case, by applying the 25 percent threshold suggested in the ANPR.

The Board's proposed threshold for treating a depository institution holding company as significantly engaged in insurance activities, and thus subject to the BBA, is set out in Section IV.B.

2. Grouping of Companies in the BBA

A preliminary question in applying the BBA is whether and, if so, how, the individual companies under an insurance depository institution holding company should be grouped before they are aggregated.

Some comments advocated an approach of keeping all companies together under a common parent as far up in the organizational structure as possible. Other comments saw merit to grouping a subsidiary IDI distinctly from an insurance parent. A number of commenters voiced views on standards for materiality or immateriality in determining whether to include companies under an insurance depository institution holding company when applying the BBA. More generally, commenters voiced openness to deeming companies immaterial if they do not pose significant risk to the insurance depository institution holding company.

The Board's proposed approach to grouping companies in an insurance depository institution holding company's enterprise in applying the BBA is set out in Section IV.C.

3. Treatment of Non-Insurance, Non-Banking Companies

In the ANPR, the Board suggested that subsidiaries not subject to capital requirements, such as some mid-tier holding companies, would be treated under the Board's banking capital rule. Commenters expressed concern that this treatment may not always be appropriate, depending on whether the subsidiary's activities are more closely aligned with insurance or banking activities in the enterprise. Commenters suggested that, where the subsidiary's activities are related to insurance operations, treating these companies under capital frameworks applicable to the operating insurance parent of such companies may be more appropriate.

The Board's proposed treatment of non-insurance, non-banking companies under the BBA is discussed further in Section IV.C.

4. Adjustments

Generally, commenters favored relatively few or modest adjustments to available capital and capital requirements under existing capital frameworks when applying the BBA. According to commenters, adjustments should be focused on addressing accounting mismatches or gaps or to eliminate double-counting. Among other things, commenters advocated adjustments to reverse intercompany transactions and ensure that adequate capital is held to reflect the risks in captive insurance companies. Specific proposed adjustments included, among others, addressing valuation differences, reversing intercompany loans and guarantees, and reversing the downstreaming of capital.

Numerous commenters advocated the use of adjustments to eliminate state permitted and prescribed accounting practices, essentially reverting insurers' accounting treatment to that prescribed by the NAIC. With regard to implementation burden, one commenter noted that it likely would not be unduly burdensome to obtain the data related to permitted and prescribed practices for purposes of applying an adjustment under the BBA.

In response to the ANPR's question on how the BBA should address intercompany transactions, commenters suggested that at least some adjustments for intercompany transactions would be necessary, with varying views on the types of transactions that should be addressed through adjustments. Commenters similarly expressed that assets and liabilities associated with intercompany transactions should not be charged twice for the risks they pose and that intercompany transactions that result in shifting risk from one subsidiary to another should be reviewed.

Many commenters expressed views that unwinding of intercompany transactions should be limited to those needed to prevent double-counting of capital. According to comments, capital should be counted only once as available capital. In particular, commenters highlighted double-leverage, whereby an upstream company's debt proceeds are infused into a downstream subsidiary as equity, resulting in equity at the subsidiary level that is offset by the liability at the parent and, hence, capital-neutral at the enterprise-level.

The proposed treatment of adjustments in the BBA is addressed in Sections VI.B and VII.B.

5. Scalars

In the BBA, existing capital requirements would be scaled to a common basis, addressing, among other things, cross-jurisdictional differences. Commenters advocated a framework for the BBA that distinguished between jurisdictions with capital frameworks suitable to be used and subjected to scalars (scalar-compatible frameworks) versus those with capital frameworks that should neither be used nor scaled (non-scalar-compatible frameworks).

A number of commenters advocated that the distinction between scalar-compatible and non-scalar-compatible frameworks should rest on three attributes that the frameworks should possess: (1) Risk-sensitivity; (2) clear regulatory intervention triggers; and (3) transparency in areas such as reserving, capital requirements, and reporting of capital measures. For material companies in a non-scalar-compatible framework, commenters suggested that their data should be restated to a scalar-compatible framework and then scaled in the BBA.

Section V of this NPR explains the Board's approach to scaling in the BBA, including the methodology adopted to produce this scaling approach.

6. Available Capital

Generally, commenters suggested that available capital under the BBA should be closely aligned with available capital permitted under state insurance laws. In its ANPR, the Board asked whether the BBA should include more than one tier of capital.[17] Commenters generally did not favor assigning available capital in the BBA to multiple tiers, citing reasons including the desire to minimize adjustments to existing capital requirements and audited financial statement data, simplicity in the BBA's design, and accounting standards' treatment of certain assets as non-admitted. Commenters further suggested that the Board can achieve its supervisory objectives with a BBA that includes a single, rather than more than one, tier of capital.

The Board's proposed approach to determining available capital under the BBA is set out in Section VII.

III. The Proposal

A. Overview of the BBA

The proposed BBA is an approach to a consolidated capital requirement that considers all material risks on an enterprise-wide basis by aggregating the capital positions of companies under an insurance holding company after expressing them in terms of a common capital framework.[18] The BBA constructs “building blocks”—or groupings of entities in the supervised firm—that are covered under the same capital framework. These building blocks are then used to calculate the combined, enterprise-level available capital and capital requirement. At the enterprise level, the ratio of the amount of available capital to capital requirement amount, termed the BBA ratio, is subject to a required minimum and buffer, with a proposed minimum of 250 percent and a proposed total buffer of 235 percent.[19]

In each building block, the BBA generally applies the capital framework for that block to the subsidiaries in that block. For instance, in a life insurance building block, subsidiaries within this block would be treated in the BBA the way they would be treated under life insurance capital requirements. In a depository institution building block, subsidiaries would be subject to Federal banking capital requirements. To address regulatory gaps and arbitrage risks, the BBA generally would apply banking capital requirements to material nonbank/non-insurance building blocks. Once the enterprise's entities are grouped into building blocks, and available capital and capital requirements are computed for each building block, the enterprise's capital position is produced by generally adding up the capital positions of each building block. The BBA is consistent with the Board's continuing emphasis on adopting tailored approaches to supervision and regulation in a manner that streamlines implementation burden.

The BBA framework was designed to produce a consolidated risk-based capital requirement that is not less stringent than the results derived from the Board's banking capital rule. To enable aggregation of available capital and capital requirements across different building blocks, the BBA proposes a mechanism (scaling) to translate a capital position under one capital framework to its equivalent in another capital framework.[20] At the enterprise level, the BBA applies a minimum risk-based capital requirement that leverages the minimum requirement from the Board's banking capital rule, expressed as its equivalent value in terms of the common capital framework. The minimum required capital ratio under the BBA begins with this equivalence value but includes a safety margin to provide a heightened degree of confidence that the BBA's requirement is not less than the generally applicable requirement. Thus, the BBA produces results that are not less stringent than the Board's banking capital rule.

In designing the BBA, the Board considered, among other things, the activities and risks of insurance institutions, existing legal entity capital requirements, input from interested parties, comments to the ANPR, and the requirements of federal law. The Board sought to develop the BBA to reflect risks across the entire firm in a manner that is as standardized as possible, rather than relying predominantly on a supervised firm's internal capital models. Furthermore, the BBA is built on U.S. regulatory and valuation standards that are appropriate for the U.S. insurance industry.

Board staff also met with interested parties, including members of the NAIC, to solicit their views on the overall development of the BBA. Input from the NAIC and states has helped identify areas of commonality between the BBA and the Group Capital Calculation (GCC) that is under development by the NAIC, achieve consistency between those frameworks wherever possible, and minimize burden upon firms that may be subject to both frameworks, while remaining respectful of the various objectives of the relevant supervisory bodies and legal environments.

These considerations exist in the context of the Board's participation in the international insurance standard-setting process and development of the international Insurance Capital Standard (ICS), an approach the Board did not follow in designing the BBA. The ICS is being developed through the International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) as a consolidated group-wide prescribed capital requirement for internationally active insurance groups (IAIGs).[21] In participating in this process, the Board remains committed to advocating, collaboratively with the NAIC, state insurance regulators, and the Federal Insurance Office, positions that are appropriate for the United States. In particular, this includes advocacy for development of an aggregation method akin to the BBA, and the GCC being developed by the NAIC, that can be deemed an outcome-equivalent approach for implementation of the ICS. In 2017, the IAIS decided to release the ICS in two phases: A five-year monitoring phase beginning in 2020, during which the ICS would be reported on a confidential basis to group-wide supervisors (the Monitoring Period), followed by an implementation phase. The IAIS released a public consultation document on ICS Version 2.0 in 2018,[22] and is planning to release ICS Version 2.0, for use in the Monitoring Period, in 2019.[23]

The purpose of the ICS Monitoring Period is to monitor the performance of the ICS over time. It is not intended to be used as supervisory mechanism to evaluate the capital adequacy of IAIGs. The ICS Monitoring Period is intended to provide a period of stability for the design and calibration of the ICS so that group-wide supervisors, with the support of supervisory colleges, may compare the ICS to existing group standards or those in development, assess whether material risks are captured and appropriately calculated, and report any difficulties encountered. Reporting during the Monitoring Period will include a reference ICS as well as additional reporting at the request of the group-wide supervisor.

The reference ICS is comprised of a market-adjusted valuation approach (MAV), which is a market-based balance sheet valuation approach similar to that used under the Solvency II framework, along with a standard method for determining capital requirements and common criteria for available capital. At the group-wide supervisor's request, ICS 2.0 will also include an alternative valuation approach, GAAP with Adjustments, that is based on local GAAP accounting rules and reporting with certain adjustments to produce results that are comparable to the reference ICS. In addition, supervisors may request information on internal models as an alternative approach for calculating risk weights. During the Monitoring Period, the IAIS will also continue with the collection of information and field-testing of the Aggregation Method.

The reference ICS may not be optimal for the Board's supervisory objectives, considering the risks and activities in the U.S. insurance market. In the United States, financial firms frequently serve a substantial role in facilitating their customers' long-term financial planning. Insurers in the United States meet consumers financial planning needs with life insurance and annuity products in addition to property/casualty products to protect personal and real property and limit liability. Insurers match life insurance and annuity long-duration products with a long-term investment strategy.

As proposed, the BBA would appropriately reflect, rather than unduly penalize, long-duration insurance liabilities in the United States. In the United States, an aggregation-based approach like the BBA could also strike a better balance between entity-level, and enterprise-wide, supervision of insurance firms.

Question 1: The IAIS is currently considering a MAV approach for the ICS; in contrast, the BBA aggregates existing company-level capital requirements throughout an organization to assess capital adequacy at various levels of the organization, including at the enterprise level. What are the comparative strengths and weaknesses of the proposed approaches? How might an aggregation-based approach better reflect the risks and economics of the insurance business in the U.S.?

Question 2: In what ways would an aggregation-based approach be a viable alternative to the ICS? What criteria should be used to assess comparability to determine whether an aggregation-based approach is outcome-equivalent to the ICS?

The Board believes that the capital requirements proposed in this NPR advance the regulatory objectives of the Board as consolidated supervisor of insurance depository institution holding companies, including ensuring enterprise-wide safety and soundness, and protecting the subsidiary IDIs. Based on the Board's preliminary review, the Board does not anticipate that any currently supervised insurance depository institution holding company will initially need to raise capital to meet the requirements of the BBA. Moreover, the BBA is consistent with the Board's continuing emphasis on adopting a tailored approach to supervision and regulation in a manner that streamlines implementation burden.

B. Dodd-Frank Act Capital Calculation

In light of the requirements of the Dodd-Frank Act, in addition to the BBA, the Board is proposing to apply a separate minimum risk-based capital requirement calculation (the Section 171 calculation) to insurance depository institution holding companies that uses the flexibility afforded under the 2014 amendments to section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Act to exclude certain state and foreign regulated insurance operations and to exempt top-tier insurance underwriting companies.

As previously discussed, section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Act requires the Board to establish minimum risk-based and leverage capital requirements for depository institution holding companies. These requirements may not be less than the “generally applicable” capital requirements for IDIs, nor quantitatively lower than the capital requirements that applied to IDIs on July 21, 2010.[24] Section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Act generally requires that the minimum risk-based capital requirements established by the Board for depository institution holding companies apply on a consolidated basis.

Notwithstanding the general requirement of section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Act that the minimum risk-based capital requirements established by the Board for depository institution holding companies apply on a consolidated basis, section 171(c) provides that the Board is not required to include for any purpose of section 171 (including in any determination of consolidation) any entity regulated by a state insurance regulator or a regulated foreign subsidiary or certain regulated foreign affiliates of such entity engaged in the business of insurance.

Currently, only a depository institution holding company that is a bank holding company or a “covered savings and loan holding company” [25] is subject to the Board's banking capital rule, which serves as the generally applicable capital requirement for IDIs and sets a floor for any capital requirements established by the Board for depository institution holding companies. Insurance depository institution holding companies are excluded from the definition of covered savings and loan holding company and from the application of the Board's banking capital rule on a consolidated basis. As a result, a top-tier SLHC that is significantly engaged in insurance activities and its subsidiary SLHCs currently are not subject to a consolidated minimum risk-based capital requirement that complies with section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Act.

Under the proposed Section 171 calculation the Board's existing minimum risk-based capital requirements would generally apply to a top-tier insurance SLHC on a consolidated basis when this company is not an insurance underwriting company. In the case of an insurance SLHC that is an insurance underwriting company, the requirements would instead apply to any insurance SLHC's subsidiary SLHC that is not itself an insurance underwriting company and is not a subsidiary of any SLHC other than the insurance SLHC, provided that the subsidiary SLHC is the farthest upstream non-insurer SLHC (i.e., the subsidiary SLHC's assets and liabilities are not consolidated with those of a holding company that controls the subsidiary for purposes of determining the parent holding company's capital requirements and capital ratios under the Board's banking capital rule) (an insurance SLHC mid-tier holding company). Except for the option to exclude insurance operations, which is described in further detail below, the minimum risk-based capital requirements that would apply for purposes of the Section 171 calculation are the same requirements that are applied under the generally applicable capital rules, and therefore ensure compliance with Section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Act.[26]

The proposed Section 171 calculation would be implemented by amending the definition of “covered savings and loan holding company” for the purposes of the Board's banking capital rule.[27] Under the proposal, an insurance SLHC would become a covered savings and loan holding company subject to the requirements of the Board's banking capital rule unless it is a grandfathered unitary savings and loan holding company that derives 50 percent or more of its total consolidated assets or 50 percent of its total revenues on an enterprise-wide basis (as calculated under GAAP) from activities that are not financial in nature.

As a result of this amendment to the definition of “covered savings and loan holding company,” insurance SLHCs generally would become subject to the minimum risk-based capital requirements in the Board's banking capital rule. However, under the proposed rule, top-tier holding companies that are engaged in insurance underwriting and regulated by a state insurance regulator, or certain foreign insurance regulators, would not be required to comply with the generally applicable risk-based capital requirements.[28] Instead, those requirements would apply to any insurance SLHC mid-tier holding companies, as defined in the proposed rule.

As noted, under the proposed Section 171 calculation, an insurance SLHC subject to the generally applicable risk-based capital requirements (i.e., that is not a top-tier insurance underwriting company) could elect not to consolidate the assets and liabilities of all of its subsidiary state-regulated insurers and certain foreign-regulated insurers. By making this election, an insurance SLHC could determine that assets and liabilities that support its insurance operations should not contribute to the calculation of risk-weighted assets or average total assets under the generally applicable capital requirements.

With regard to the regulatory capital treatment of an insurance SLHC's (or insurance mid-tier holding company's) equity investment in subsidiary insurers that do not consolidate assets and liabilities with the holding company pursuant to the election, the proposal presents two alternative approaches for comment.[29] Under the first alternative, the holding company could elect to deduct the aggregate amount of its outstanding equity investment in its subsidiary state- and certain foreign-regulated insurers, including retained earnings, from its common equity tier 1 capital elements. Under the second alternative, the holding company could include the amount of its investment in its risk-weighted assets and assign to the investment a 400 percent risk weight, consistent with the risk weight applicable under the simple risk-weight approach in section 217.52 of the Board's banking capital rule to an equity exposure that is not publicly traded.[30] The Board recognizes that fully deducting from common equity tier 1 capital an insurance SLHC's equity investment in insurance subsidiaries in some cases could yield inaccurate or overly conservative results for the section 171 calculation, for example, where the holding company has issued debt to fund equity contributions to the insurance subsidiaries. Conversely, any risk weight approach for equity investments in insurance subsidiaries must be calibrated to reflect risk, facilitate comparability of capital requirements for insurance and non-insurance depository institution holding companies, and avoid creating incentives for regulatory arbitrage. The Board continues to consider these issues, and invites comment on optional approaches to exclude insurance operations from the calculation of consolidated regulatory capital requirements.

As previously noted, in addition to risk-based capital requirements, section 171 requires the Board to establish minimum leverage capital requirements for depository institution holding companies. The Board's banking capital rule includes a minimum leverage ratio of 4 percent tier 1 capital to average total assets.[31] The Board is not currently proposing a leverage capital requirement for insurance SLHCs under the BBA framework or as part of the section 171 compliance calculation, and continues to evaluate methodologies to apply leverage capital requirements to these institutions.

Question 3: As an alternative to consolidation, what are the advantages or disadvantages of permitting a holding company to deconsolidate the assets and liabilities of its subsidiary state- and certain foreign-regulated insurers, and deduct from equity its investment in these subsidiary insurers?

Question 4: As an alternative to consolidation, what are the advantages or disadvantages of permitting a holding company to deconsolidate the assets and liabilities of its subsidiary state- and certain foreign-regulated insurers, and risk weight the holding company's equity investment in these subsidiary insurers?

Question 5: What is the appropriate risk weighting for a holding company's equity investment in its subsidiary state- and certain foreign-regulated insurers?

Question 6: What other calculations, if any, should the Board consider to ensure that the minimum risk-based capital requirement for insurance depository institution holding companies complies with section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Act?

Question 7: Should the generally applicable minimum leverage ratio be excluded from the section 171 calculation?

Question 8: What are the advantages or disadvantages of applying the generally applicable minimum leverage capital requirement to an insurance SLHC or insurance SLHC mid-tier holding company, as defined in this proposal, with the same exclusion of insurance subsidiaries as set out in this proposal for the generally applicable minimum risk-based capital requirement?

Question 9: What are the advantages or disadvantages of applying a supplementary leverage ratio requirement to an insurance SLHC or insurance SLHC mid-tier holding company, as defined in this proposal, with the same exclusion of insurance subsidiaries as set out in this proposal for the generally applicable minimum risk-based capital requirement?

A holding company electing to de-consolidate the assets and liabilities of all of its subsidiary state- and certain foreign regulated insurers would make this election, and indicate the manner in which it will account for its equity investment in such subsidiaries, on the applicable regulatory report filed by the holding company for the first reporting period in which it is subject to the Section 171 calculation. A holding company seeking to make such an election at a later time, or to change its election due to a change in control, business combination, or other legitimate business purpose, would be required to receive the prior approval of the Board.

Question 10: What would the benefits and costs be of allowing a holding company to elect not to consolidate some, but not all, of its subsidiary state- and certain foreign-regulated insurers?

Question 11: When should the Board permit a holding company to request to change a prior election regarding the capital treatment of its insurance subsidiaries?

IV. The Building Block Approach

A. Structure of the BBA

The proposed BBA is an approach to a consolidated capital requirement that aggregates the capital positions of companies under an insurance depository institution holding company, adjusted as prescribed in the proposed rule, and scaled to a common capital framework. The proposed BBA would group companies into subsets of the full enterprise, called building blocks, where the company that owns or controls each building block is termed a “building block parent.” The purpose of a building block is to group together companies generally falling under the same capital framework (namely, the framework of the building block parent). Each building block parent's applicable capital framework would be used to determine that parent's capital position.[32] The proposed BBA would scale or convert the capital positions of non-insurance building block parents to their insurance building block parent equivalents and then aggregate the capital positions to reach an enterprise-wide capital position. In this manner, the BBA reflects the risks and resources of the subsidiaries within each building block and, thus, a consolidation of all material risks in the insurance depository institution holding company's enterprise.

An important part of applying the BBA is identifying the building block parents in an insurance depository institution holding company's enterprise. Section IV.C below discusses the steps to determine the building block parents, including identifying an inventory of companies from which building block parents are identified based on the applicable capital framework assigned to the companies for use in the BBA. Ultimately, all of the building blocks are aggregated into the top-tier depository institution holding company's building block, thereby resulting in an amount of available capital and capital requirement for the top-tier depository institution holding company used to calculate its BBA ratio.

B. Covered Institutions and Scope of the BBA

The proposed BBA would apply to depository institution holding companies significantly engaged in insurance activities. The Board proposed in the ANPR that a firm would be subject to the BBA if the top-tier parent were an insurance underwriting company or 25 percent of its total assets were in insurance underwriting subsidiaries. In this NPR, the Board proposes to leave this threshold unchanged. A firm would be subject to the BBA if: (1) The top-tier DI holding company is an insurance underwriting company; (2) the top-tier DI holding company, together with its subsidiaries, holds 25 percent or more of its total consolidated assets in insurance underwriting subsidiaries (other than assets associated with insurance underwriting for credit risk related to bank lending); [33] or (3) the firm has otherwise been made subject to the BBA by the Board.

As consolidated supervisor of the top-tier DI holding company of an insurance depository institution holding company, the Board proposes to include, within the scope of the BBA calculation, all owned or controlled subsidiaries of this top-tier parent.[34] While the Board could have opted to exclude certain subsidiaries (e.g., those that are immaterial), the Board considers that a capital requirement including all owned or controlled companies within the scope of the BBA better reflects a consolidated, enterprise-wide perspective of the risks faced by the insurance depository institution holding company. Companies that are not owned or controlled by a top-tier DI holding company and that do not own or control an IDI would fall outside of the BBA's scope. For instance, a top-tier DI holding company may have a sister company that does not control an IDI. The sister company would fall outside of the scope of the BBA's application because it lacks the requisite connection to the IDI. Under a different structure, an insurance depository institution holding company may control an IDI that is also controlled by another insurance depository institution holding company, where both insurance depository institution holding companies are part of the same organization generally regarded as a single group. Both of these top-tier DI holding companies would be within the BBA's scope.

Currently, the insurance depository institution holding companies are all SLHCs and the current proposed definition of top-tier depository institution holding company in the BBA only encompasses SLHCs. However, it is possible for a bank holding company (which is also a depository institution holding company under the FDI Act) to be significantly engaged in insurance activities as determined by applying the threshold described earlier in this section. In particular, under the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (EGRRCPA),[35] Federal savings associations with total consolidated assets of up to $20 billion, as reported to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) as of year-end 2017, may elect to operate as a covered savings association.[36] The Board is still considering these recent legislative changes. However, the Board presently does not see reason to apply different capital requirements to an insurance depository institution holding company that controls a covered savings association and an insurance depository institution holding company that controls any other IDI. Preliminarily, the Board anticipates harmonizing the regulation of BHCs and SLHCs significantly engaged in insurance activities, in each case determined by applying the threshold described earlier in this section. This could result in BHCs significantly engaged in insurance activities falling within the scope of the final rule implementing the BBA.

Question 12: What are the advantages and disadvantages of including all insurance depository institution holding companies (including bank holding companies significantly engaged in insurance activities and insurance depository institution holding companies that control covered savings associations) within the scope of the final BBA rule, as planned?

C. Identification of Building Blocks and Building Block Parents

1. Inventory

In order to identify the set of companies that would be grouped into building blocks and aggregated, an insurance depository institution holding company would first identify an inventory of all companies in its enterprise. Some of the companies in the inventory would be building block parents. The remaining companies would be assigned to building block parents.

To construct the inventory, the Board prefers including a broad set of companies that reflects the firm's full enterprise under the BBA's scope and provides an appropriately wide range of candidates for building block parents. A framework for constructing the inventory that relied on, for instance, the definitions of “control” under U.S. GAAP may be burdensome to apply and set a relatively higher bar for inclusion of affiliates, resulting in too few companies appearing on the inventory. The Board notes that the NAIC's Schedule Y, filed annually as part of the SAP financial statements, is advantageous in utilizing a standard for “control” that enables more subsidiaries and affiliates to be included.

Because it is possible that certain banking, SLHC, or nonbanking companies may not appear on the supervised firm's Schedule Y (but would appear on the firm's regulatory filings with the Board), the Board sought to augment the inventory by adding to the set of companies obtained from Schedule Y the companies appearing on the Board's Forms FR Y-6 and FR Y-10. These forms use a definition of control setting out scenarios where one company has control over another through a variety of ways, including ownership, control of voting securities, and management agreements. The Board considers that through the combination of companies appearing on Forms FR Y-6 and FR Y-10, and the NAIC's Schedule Y,[37] the BBA would reflect a sufficiently wide set of companies as potential building block parents as well as capturing all material risks. Moreover, by utilizing reports already prepared by insurance depository institution holding companies, including those reported to state insurance regulators, the BBA proposal aims to minimize burden in the process of inventorying companies.

While the inventory in the BBA will generally comprise the companies shown on the forms discussed above, the Board also seeks to ensure that the supervised firm's organizational and control structure does not materially alter the scope of risks that the BBA considers. Firms may engage in transactions with counterparties not shown on these forms, where these transactions have the effect of transferring risk or evading application the BBA. For such circumstances, the BBA includes a mechanism to include these counterparties in the inventory.

As discussed below, applying the BBA and performing its calculations rests on identifying the building block parents among the companies in the inventory. Once these building block parents are identified, all of their subsidiaries, whether or not listed on the inventory, would fall within the scope of the BBA.

An illustration of this step in applying the BBA is presented in Section IX.A.

2. Applicable Capital Framework

In the BBA, the term “applicable capital framework” refers to a regulatory capital framework that is used to determine whether a company should be a building block parent, and, once a company is assigned to a building block, to measure the capital resources of that company and the amount of risk the company contributes to the overall enterprise. Once a company is identified as a building block parent, its applicable capital framework would be used to reflect the capital position across all of the subsidiaries in the building block, including subsidiaries that are not directly subject to any regulatory capital framework.

For the insurance operations, insurance capital requirements are likely to best reflect the underlying risks.[38] For instance, the applicable capital framework for U.S. insurance operating companies may be life or property and casualty (P&C) risk-based capital (RBC). The Board's proposal to use the regulatory capital framework promulgated by the NAIC for an insurance company or operation as the applicable capital framework (e.g., the P&C RBC for a P&C insurer) takes into consideration the NAIC capital framework's reflection of the potential impact of various risk exposures, including liabilities, on the solvency of that type of insurer. For material insurance companies that lack a regulatory capital framework for which scaling can be performed under the BBA, such as some captive insurance companies, the Board proposes to apply the NAIC's RBC, after restating such companies' financial information according to SAP.[39]

For banking companies, the Board was mindful of the reflection of risks in the banking capital requirements. The Board proposes to incorporate the regulatory capital framework established for a depository institution by its primary Federal banking regulator as the depository institution's applicable capital framework, because the capital framework has been calibrated to reflect the potential impact of various risk exposures common to banking organizations (primarily in the form of assets) on the risk profile of a depository institution. In particular, an IDI's applicable capital framework is determined as follows: [40] For nationally-chartered IDIs, the applicable capital framework is the capital rule as set forth by the OCC.[41] For state-chartered IDIs that are members of the Federal Reserve System, the applicable capital framework is the Board's banking capital rule, and for those that are not members, the capital rule as set forth by the FDIC.[42] In addition, applying bank capital requirements to certain other non-insurance subsidiaries, referred to in the BBA as “material financial entities” (MFEs), can mitigate the risk of regulatory arbitrage by disincentivizing the reallocation of assets between banking, insurance, and other companies in the institution. Where the rule proposes to apply Federal bank capital rules, insurance depository institution holding companies would apply them using the same elections (e.g., treatment of accumulated other comprehensive income) as they would when applying bank capital rules to a subsidiary IDI.[43]

The Board proposes to include, within the scope of the BBA, the insurance depository institution holding company predominantly engaged in title insurance through a tailored application of the Board's banking capital rule.[44] The NAIC has not promulgated a risk-based capital standard for title insurance companies. In the absence of an insurance capital framework for title insurance, and in light of the different nature of title insurance compared with life and P&C insurance, the Board has determined to apply the Board's banking capital rule to an insurance depository institution holding company predominantly engaged in title insurance. Currently, there is one insurance depository institution holding company that is predominantly engaged in title insurance. The Board's proposed application of the BBA to this firm is facilitated by the fact that the title insurance depository institution holding company, like other large title insurers, prepares consolidated financial statements in accordance with U.S. GAAP.

As a simplified example of the determination of companies' applicable capital frameworks, consider an insurance depository institution holding company consisting of a life insurance top-tier parent with two subsidiaries, a P&C insurer and the IDI. Each of these companies would fall under a different applicable capital framework, namely, for the top-tier parent, NAIC RBC for life insurance; for the P&C subsidiary, NAIC RBC for P&C insurance; and for the IDI, the appropriate Federal banking capital rule. A further illustration of this step in applying the BBA is presented in Section IX.B.

Question 13: The Board invites comment on the proposed approach to determine applicable capital frameworks. What are the advantages and disadvantages of the approach? What is the burden associated with the proposed approach?

3. Building Block Parents

Under the proposed BBA, a building block parent can be one of several different types of companies. The first is the top-tier depository institution holding company. In the absence of any other identified building block parents, the top-tier depository institution holding company's building block would contain all of the top-tier depository institution holding company's subsidiaries. A second type of building block parent is a mid-tier holding company that is a “depository institution holding company” under U.S. law. Treating these companies as building block parents will allow for the calculation of a separate BBA ratio at the level of these companies in the enterprise and help to ensure that these companies remain appropriately capitalized. The balance of this subsection discusses the remaining types of building block parents.

(a) Capital-Regulated Companies and Material Financial Entities as Building Block Parents

For two categories of companies that could be identified as building block parents, companies that are subject to company-level capital requirements (capital-regulated companies) and MFEs, the analysis is conducted in the same manner. For each of these companies in the inventory, the supervised firm analyzes whether that company's applicable capital framework differs from that of the next capital-regulated company, MFE, or DI holding company encountered when proceeding upstream in the supervised firm's inventory. If so, that company is identified as a building block parent. The identification of building block parents, particularly capital-regulated companies and material financial entities, can be illustrated through the following decision tree, which would be applicable for each company in the insurance depository institution holding company's enterprise.

For example, if a firm's top-tier depository institution holding company is a life insurer that has two direct subsidiaries—a P&C insurer and the IDI—the firm would analyze whether the P&C company's applicable capital framework (NAIC RBC for P&C insurers) differs from that of the top-tier DI holding company (NAIC RBC for life insurers). Upon finding that the applicable capital frameworks are different, the P&C insurer would be a building block parent. The same would be the case for the IDI, whose applicable capital framework (a Federal banking capital rule) differs from the capital framework of its life insurance parent. However, if the P&C subsidiary has a further downstream P&C subsidiary, the firm would compare the latter P&C company's applicable capital framework only against that the P&C subsidiary immediately below the life insurer.[45] Thus, the downstream P&C subsidiary would not be identified as a building block parent.

If the capital framework of a capital-regulated company or MFE is the same as that of the next-upstream capital-regulated company, MFE, or DI holding company, generally the companies will remain in the same building block except for one case. This exceptional case is where a company's applicable capital framework treats the company's subsidiaries in a way that does not substantially reflect the subsidiary's risk. For instance, there are situations in which NAIC RBC may not fully reflect the risks in certain subsidiaries (typically, certain foreign subsidiaries) that assume risk from affiliates.[46] In such cases, the subsidiary (which could be a capital-regulated company or MFE) would be identified as a building block parent so that its risks can more appropriately be reflected in the BBA.

While the current population of insurance depository institution holding companies does not include material non-U.S. operations, additional considerations in identifying capital-regulated companies as building block parents may arise in cases of an insurance depository institution holding company's insurance subsidiaries subject to non-U.S. capital frameworks. Whether such companies can be identified as building block parents depends on whether the companies' applicable capital frameworks can be scaled to NAIC RBC, the common capital framework used in the BBA. If a scalar has been developed for the applicable capital framework, the capital-regulated non-U.S. insurance subsidiary would be identified as a building block parent. Where a scalar has not been developed for the applicable capital framework, but the aggregate of the enterprise's companies falling under the non-U.S. insurance capital framework is material,[47] the BBA proposes a provisional scaling approach so that these companies could be identified as building block parents. In all other cases, capital-regulated non-U.S. insurance subsidiaries would not be identified as building block parents.

As discussed above, an MFE is a financial entity that is material, subject to certain exclusions. The proposed definition of “financial entity” in the BBA enumerates several types of companies engaged in financial activity consistent with similar enumerations in other rules applied by the Board. To develop the proposed definition of “financial entity,” the Board began with the definition of the same term under the Board's existing rules,[48] and made modifications to tailor to insurance enterprises and the BBA (principally, the removal of the prong for employee benefit plans, since these are unlikely to exist under insurance depository institution holding companies).

The proposed definition of materiality consists of two parts. In the first part, a company is presumed to be material if the top-tier depository institution holding company has exposure to the company exceeding 1 percent of the top-tier's total assets.[49] In this context, “exposure” includes:

- The absolute value of the top-tier depository institution holding company's direct or indirect interest in the company's capital;

- the top-tier depository institution holding company or any of its subsidiaries providing an explicit or implicit guarantee for the benefit of the company; and

- potential counterparty credit risk to the top-tier depository institution holding company or any subsidiary arising from any derivatives or similar instrument, reinsurance or similar arrangement, or other contractual agreement.

There may be cases in which these enumerated presumptions may not fully capture subsidiaries that are otherwise material. To accommodate these cases, the second part of the proposed definition of “material” would consider a subsidiary to be material when it is significant in assessing the insurance depository institution holding company's available capital or capital requirements. Factors that indicate such significance include risk exposure, activities, organizational structure, complexity, affiliate guarantees or recourse rights, and size.[50] This definition, tailored to insurance and the BBA, accords with the Board's prior rulemakings and actions utilizing considerations of materiality.[51]

Question 14: What other definitions of materiality, if any, should the Board consider for use in the BBA? Examples may include a threshold based on size, off-balance sheet exposure, or activities including derivatives or securitizations.

Question 15: What thresholds, other than the proposed threshold for exposure as a percentage of total assets, should the Board consider for use in the BBA's definition of materiality? What are advantages and disadvantages of using a threshold based on the top-tier depository institution holding company's building block capital requirement? [52]

The notion of a material financial entity is proposed to address a variety of companies not subject to a capital requirement and that could pose risk to the safety and soundness of the insurance depository institution holding company or its subsidiary IDI. For instance, an insurance depository institution holding company may have a material derivatives trading subsidiary not presently subject to any capital framework. Additionally, a company under an insurance depository institution holding company may serve as a funding vehicle for other companies in the institution, borrowing and downstreaming funds to affiliates.

Among other companies that could be MFEs are certain insurance companies that exist to reinsure risk from affiliates. The Board proposes that when such companies, and the insurance depository institution holding company's use of and transactions with such companies, could pose material financial risk to the insurance depository institution holding company, such companies' financial information should be restated in accordance with SAP.[53] Such companies as restated should be subjected to capital treatment under RBC and included in the BBA as MFEs.

The BBA includes certain exceptions whereby companies that are financial entities and material would nonetheless not be treated as MFEs. Where a company primarily functions as an intermediary through which other companies within the insurance depository institution holding company's enterprise conduct activities (e.g., manage or hedge risk through the use of reinsurance or derivatives or investment partnerships), the proposed BBA allows the insurance depository institution holding company to elect to not treat such a company as an MFE. In such a case, the firm would be required to allocate the company's risks to other companies within the insurance depository institution holding company's enterprise.

In addition, the Board proposes that certain types of companies would be ineligible to be MFEs: A financial subsidiary as defined in GLBA Section 121 and a subsidiary primarily engaged in asset management. In the case of a financial subsidiary, the equity of these subsidiaries is deducted, and the assets and liabilities not consolidated, under the Board's banking capital rules. Treating such a subsidiary as an MFE, and calculating qualifying capital and RWA for such a subsidiary, may not fully accord with the Board's current banking capital rules.

In the case of a subsidiary primarily engaged in asset management, the Board considers that a registered investment adviser under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 would not be an MFE. As a non-insurance company, the applicable capital regime under the BBA for an investment adviser would be the Federal banking capital rules. These rules are built on the calculation of RWA and presently do not have dedicated, robust, and risk-sensitive treatment of operational risk. Moreover, investment advisers do not typically report all assets under management on their balance sheets and can face substantial operational risk. As such, measuring these subsidiaries' capital positions using the Board's banking capital rules may not provide a complete depiction of the subsidiaries' risks. Furthermore, in insurers' organizational structures, asset manager subsidiaries can exist under non-operating or shell holding companies. To the extent that such holding companies under insurance depository institution holding companies are not engaged in financial activities, they would not constitute financial entities under the BBA.

Question 16: The Board invites comment on the use of the material financial entity concept. What are the advantages and disadvantages to the approach? What burden, if any, is associated with the proposed approach?

Question 17: The Board invites comment on the proposed treatment of intermediaries. What are the advantages and disadvantages of the approach? What burden, if any, is associated with the proposed treatment?

Question 18: What risk-sensitive approaches could be used to address the risks presented by asset managers in an insurance depository institution holding company's enterprise?

Question 19: What forms or structures, if any, do asset managers or their holding companies take in insurance enterprises, such that they may fall within the proposed definition of an MFE?

(b) Other Instances of Building Block Parents

The BBA allows for three additional cases in which a company is identified as a building block parent. First, a company is a building block parent when it is:

- Party to one or more reinsurance or derivative transactions with other inventory companies;

- Material; and

- Engaged in activities such that one or more inventory companies are expected to absorb more than 50 percent of its expected losses.

Second, the case could arise where a company under an insurance depository institution holding company is jointly owned by more than one building block parent, where the jointly owned company is not itself a building block parent. Furthermore, the company may be consolidated in the applicable capital framework of one or more of the building block parents. In such a case, the aggregation in the BBA could result in double counting of the risks and resources of the jointly-owned company. To avoid this outcome, the proposed BBA would identify the jointly-owned company as a building block parent, whereupon the aggregation and consideration of allocation shares, discussed below, would avoid double-counting.

Finally, depending on an insurance depository institution holding company's organizational structure, it may be more convenient or less burdensome to treat, as a building block parent, a company that is not identified as such through the operations described above, or vice versa.

Each of these cases of identifying or declining to identify building block parents is achieved through the reservation of authority provision proposed in the BBA.[54] Factors that the Board may consider in determining to treat or not treat a company in an insurance depository institution holding company's enterprise as a building block parent in this manner include, but are not limited to, operational ease or convenience in applying the BBA, adequate risk sensitivity and reflection of risks posed to the safety and soundness of the supervised institution and/or its subsidiary IDI, and minimizing implementation burden in the insurance depository institution holding company's fulfillment of regulatory reporting and compliance requirements.[55] Moreover, certain transaction structures result in material risks being moved outside of regulatory capital frameworks, or moved to regulatory capital frameworks that do not fully reflect these risks.[56] The BBA accommodates such scenarios by reserving for the Board the authority to make adjustments to the set of inventory companies that are building block parents.

An illustration of this step in applying the BBA is presented in Section IX.C below.