AGENCY:

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS.

ACTION:

Final rule with comment period.

SUMMARY:

This final rule with comment period updates the home health prospective payment system (HH PPS) payment rates and wage index for CY 2020; implements the Patient-Driven Groupings Model (PDGM), a revised case-mix adjustment methodology, for home health services beginning on or after January 1, 2020. This final rule with comment period also implements a change in the unit of payment from 60-day episodes of care to 30-day periods of care, as required by section 51001 of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, hereinafter referred to the “BBA of 2018”, and finalizes a 30-day payment amount for CY 2020. Additionally, this final rule with comment period: Modifies the payment regulations pertaining to the content of the home health plan of care; allows therapist assistants to furnish maintenance therapy; and changes the split percentage payment approach under the HH PPS. For the Home Health Value-Based Purchasing (HHVBP) model, we are finalizing provisions requiring the public reporting of the Total Performance Score (TPS) and the TPS Percentile Ranking from the Performance Year 5 (CY 2020) Annual TPS and Payment Adjustment Report for each home health agency in the nine Model states that qualified for a payment adjustment for CY 2020. This final rule with comment period also finalizes the following updates to the Home Health Quality Reporting Program (HH QRP): Removal of a measure; adoption of two new measures; modification of an existing measure; and a requirement for HHA's to report standardized patient assessment data beginning with the CY 2022 HH QRP. Additionally, we are finalizing our proposal to re-designate our current HH QRP regulations in a different section of our regulations and to codify other current policies in that new regulatory section with one substantive change as well as a few technical edits. We are not finalizing our proposal to remove question 10 from all of the HH Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) surveys. Lastly, it sets forth routine updates to the home infusion therapy payment rates for CY 2020, payment provisions for home infusion therapy services for CY 2021 and subsequent years, and solicits comments on options to enhance future efforts to improve policies related to coverage of eligible drugs for home infusion therapy.

DATES:

Effective Date: This final rule with comment period is effective January 1, 2020.

Comment Date: To be assured consideration, comments on the criteria that can be considered to allow coverage of additional drugs under the DME benefit discussed in section VI.D. of this final rule with comment period must be received at one of the addresses provided below, no later than 5 p.m. on December 30, 2019.

ADDRESSES:

In commenting, please refer to file code CMS-1711-FC. Because of staff and resource limitations, we cannot accept comments by facsimile (FAX) transmission.

Comments, including mass comment submissions, must be submitted in one of the following three ways (please choose only one of the ways listed):

1. Electronically. You may submit electronic comments on this regulation to http://www.regulations.gov. Follow the “Submit a comment” instructions.

2. By regular mail. You may mail written comments to the following address ONLY: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services, Attention: CMS-1711-FC, P.O. Box 8013, Baltimore, MD 21244-8013.

Please allow sufficient time for mailed comments to be received before the close of the comment period.

3. By express or overnight mail. You may send written comments to the following address ONLY: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services, Attention: CMS-1711-FC, Mail Stop C4-26-05, 7500 Security Boulevard, Baltimore, MD 21244-1850.

For information on viewing public comments, see the beginning of the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION section.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Hillary Loeffler, (410) 786-0456, for Home Health Prospective Payment System (HH PPS) or home infusion payment.

For general information about the Home Health Prospective Payment System (HH PPS), send your inquiry via email to: HomehealthPolicy@cms.hhs.gov.

For general information about home infusion payment, send your inquiry via email to: HomeInfusionPolicy@cms.hhs.gov.

For information about the Home Health Value-Based Purchasing (HHVBP) Model, send your inquiry via email to: HHVBPquestions@cms.hhs.gov.

For information about the Home Health Quality Reporting Program (HH QRP), send your inquiry via email to HHQRPquestions@cms.hhs.gov.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Inspection of Public Comments: All comments received before the close of the comment period are available for viewing by the public, including any personally identifiable or confidential business information that is included in a comment. We post all comments received before the close of the comment period on the following website as soon as possible after they have been received: http://www.regulations.gov. Follow the search instructions on that website to view public comments.

Table of Contents

I. Executive Summary

A. Purpose

B. Summary of the Major Provisions

C. Summary of Costs and Benefits

II. Overview of the Home Health Prospective Payment System (HH PPS)

A. Statutory Background

B. Current System for Payment of Home Health Services

C. New Home Health Prospective Payment System for CY 2020 and Subsequent Years

D. Analysis of CY 2017 HHA Cost Report Data

III. Payment Under the Home Health Prospective Payment System (HH PPS)

A. Implementation of the Patient-Driven Groupings Model (PDGM) for CY 2020

B. Implementation of a 30-Day Unit of Payment for CY 2020

C. CY 2020 HH PPS Case-Mix Weights for 60-Day Episodes of Care Spanning Implementation of the PDGM

D. CY 2020 PDGM Case-Mix Weights and Low-Utilization Payment Adjustment (LUPA) Thresholds

E. CY 2020 Home Health Payment Rate Updates

F. Payments for High-Cost Outliers under the HH PPS

G. Changes to the Split-Percentage Payment Approach for HHAs in CY 2020 and Subsequent Years

H. Change To Allow Therapist Assistants To Perform Maintenance Therapy

I. Changes to the Home Health Plan of Care Regulations at § 409.43

IV. Home Health Value-Based Purchasing (HHVBP) Model

A. Background

B. Public Reporting of Total Performance Scores and Percentile Rankings Under the HHVBP Model

C. Removal of Improvement in Pain Interfering With Activity Measure (NQF #0177)

V. Home Health Quality Reporting Program (HH QRP)

A. Background and Statutory Authority

B. General Considerations Used for the Selection of Quality Measures for the HH QRP

C. Quality Measures Currently Adopted for the CY 2021 HH QRP

D Removal of HH QRP Measures Beginning With the CY 2022 HH QRP

E. New and Modified HH QRP Quality Measures Beginning With the CY 2022 HH QRP

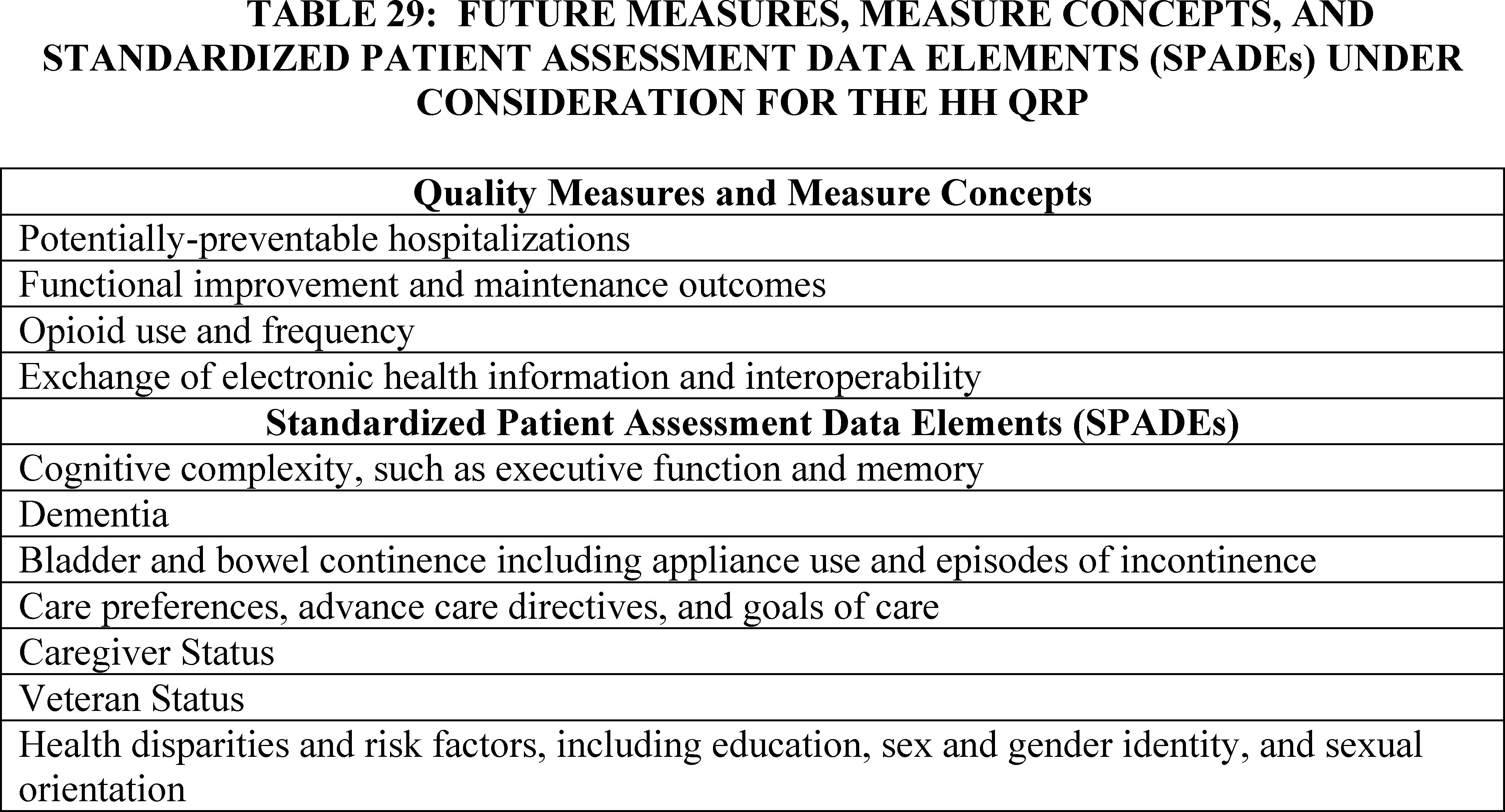

F. HH QRP Quality Measures, Measure Concepts, and Standardized Patient Assessment Data Elements Under Consideration for Future Years: Request for Information

G. Standardized Patient Assessment Data Reporting Beginning With the CY 2022 HH QRP

H. Standardized Patient Assessment Data by Category

I. Form, Manner, and Timing of Data Submission Under the HH QRP

J. Codification of the Home Health Quality Reporting Program Requirements

K. Home Health Care Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS®) Survey (HHCAHPS)

VI. Medicare Coverage of Home Infusion Therapy Services

A. Background and Overview

B. CY 2020 Temporary Transitional Payment Rates for Home Infusion Therapy Services

C. Home Infusion Therapy Services for CY 2021 and Subsequent Years

D. Payment Categories and Amounts for Home Infusion Therapy Services for CY 2021

E. Required Payment Adjustments for CY 2021 Home Infusion Therapy Services

F. Other Optional Payment Adjustments/Prior Authorization for CY 2021 Home Infusion Therapy Services

G. Billing Procedures for CY 2021 Home Infusion Therapy Services

VII. Waiver of Proposed Rule

VIII. Collection of Information Requirements

IX. Regulatory Impact Analysis

A. Statement of Need

B. Overall Impact

C. Anticipated Effects

D. Detailed Economic Analysis

E. Alternatives Considered

F. Accounting Statement and Tables

G. Regulatory Reform Analysis Under E.O. 13771

H. Conclusion

Regulation Text

I. Executive Summary

A. Purpose

1. Home Health Prospective Payment System (HH PPS)

This final rule with comment period updates the payment rates for home health agencies (HHAs) for calendar year (CY) 2020, as required under section 1895(b) of the Social Security Act (the Act). This rule also updates the case-mix weights under section 1895(b)(4)(A)(i) and (b)(4)(B) of the Act for 30-day periods of care beginning on or after January 1, 2020. This final rule with comment period implements the PDGM, a revised case-mix adjustment methodology that was finalized in the CY 2019 HH PPS final rule with comment period (83 FR 56406), which also implements the removal of therapy thresholds for payment as required by section 1895(b)(4)(B)(ii) of the Act, as amended by section 51001(a)(3) of the BBA of 2018, and changes the unit of home health payment from 60-day episodes of care to 30-day periods of care, as required by section 1895(b)(2)(B) of the Act, as amended by 51001(a)(1) of the BBA of 2018. This final rule with comment period allows therapist assistants to furnish maintenance therapy; finalizes changes to the payment regulations pertaining to the content of the home health plan of care; updates technical regulations text changes which clarifies the split-percentage payment approach for newly-enrolled HHAs in CY 2020 and changes the split percentage payment approach for existing HHAs in CY 2020 and subsequent years.

2. HHVBP

This final rule with comment period finalizes public reporting of the Total Performance Score (TPS) and the TPS Percentile Ranking from the Performance Year 5 (CY 2020) Annual TPS and Payment Adjustment Report for each HHA that qualifies for a payment adjustment under the HHVBP Model for CY 2020.

3. HH QRP

This final rule with comment period finalizes changes to the Home Health Quality Reporting Program (HH QRP) requirements under the authority of section 1895(b)(3)(B)(v) of the Act.

4. Home Infusion Therapy

This final rule with comment period finalizes payment provisions for home infusion therapy services for CY 2021 and subsequent years in accordance with section 1834(u) of the Act, as added by section 5012 of the 21st Century Cures Act (Pub. L. 114-255).

B. Summary of the Major Provisions

1. Home Health Prospective Payment System (HH PPS)

Section III.A. of this final rule with comment period sets forth the implementation of the Patient-Driven Groupings Model (PDGM) as required by section 51001 of the BBA of 2018 (Pub. L. 115-123). The PDGM is an alternate case-mix adjustment methodology to adjust payments for home health periods of care beginning on and after January 1, 2020. The PDGM relies more heavily on clinical characteristics and other patient information to place patients into meaningful payment categories and eliminates the use of therapy service thresholds, as required by section 1895(b)(4)(B) of the Act, as amended by section 51001(a)(3) of the BBA of 2018. Section III.B. of this final rule with comment period implements a change in the unit of payment from a 60-day episode of care to a 30-day period of care as required by section 1895(b)(2) of the Act, as amended by section 51001(a)(1) of the BBA of 2018. Section 1895(b)(3) of the Act requires that we calculate this 30-day payment amount for CY 2020 in a budget-neutral manner such that estimated aggregate expenditures under the HH PPS during CY 2020 are equal to the estimated aggregate expenditures that otherwise would have been made under the HH PPS during CY 2020 in the absence of the change to a 30-day unit of payment. The CY 2020 30-day payment amount (for those HHAs that report the required quality data) will be $1,864.03, which reflects an adjustment of −4.36 percent to maintain overall budget neutrality under the PDGM.

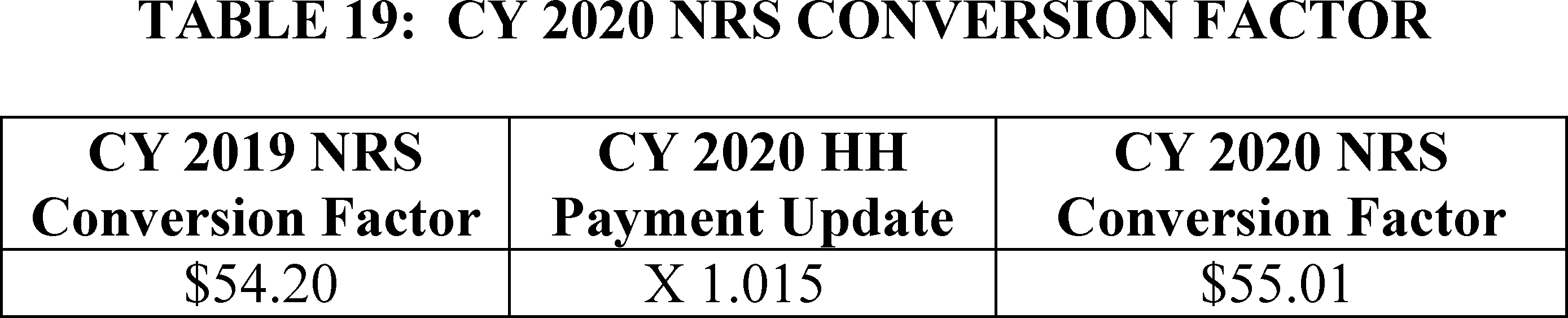

Section III.C. of this final rule with comment period describes the CY 2020 case-mix weights for those 60-day episodes that span the implementation date of the PDGM and section III.D. of this rule finalizes the CY 2020 PDGM case-mix weights and LUPA thresholds for 30-day periods of care. In section III.E. of this final rule, we finalize update the home health wage index and to update the national, standardized 60-day episode of care and 30-day period of care payment amounts, the national per-visit payment amounts, and the non-routine supplies (NRS) conversion factor for 60-day episodes of care that begin in 2019 and span the 2020 implementation date of the PDGM. The home health payment update percentage for CY 2020 is 1.5 percent, as required by section 53110 of the BBA of 2018. Section III.F. of this final rule with comment period, finalizes changes change to the fixed-dollar loss ratio to 0.56 for CY 2020 under the PDGM in order to ensure that outlier payments as a percentage of total payments is closer to, but no more than, 2.5 percent, as required by section 1895(b)(5)(A) of the Act. Section III.G. of this final rule with comment period, finalized technical regulations correction at § 484.205 regarding split-percentage payments for newly-enrolled HHAs in CY 2020; and finalizes the following additional changes to the split-percentage payment approach: (1) A reduction in the up-front amount paid in response to a Request for Anticipated Payment (RAP) to 20 percent of the estimated final payment amount for both initial and subsequent 30-day periods of care for CY 2020; (2) a reduction to the up-front amount paid in response to a RAP to zero percent of the estimated final payment amount for both initial and subsequent 30-day periods of care with a late submission penalty for failure to submit the RAP within 5 calendar days of the start of care for the first 30-day period within a 60-day certification period and within 5 calendar days of day 31 for the second, subsequent 30-day period in a 60-day certification period for CY 2021; (3) the elimination of the split-percentage payment approach entirely in CY 2022, replacing the RAP with a one-time submission of a Notice of Admission (NOA) with a late submission penalty for failure to submit the NOA within 5 calendar days of the start of care. In section III.H. of this final rule with comment period, we are finalizing our proposal to allow therapist assistants to furnish maintenance therapy under the Medicare home health benefit, and section III.I. of this final rule with comment period, we finalize a change in the payment regulation text at § 409.43 related to home health plan of care requirements for payment.

2. HHVBP

In section IV. of this final rule with comment period, we are finalizing provisions requiring public reporting performance data for Performance Year (PY) 5 of the HHVBP Model. Specifically, we are finalizing the public reporting of the TPS and the TPS Percentile Ranking from the PY 5 (CY 2020) Annual TPS and Payment Adjustment Report for each HHA in the nine Model states that qualified for a payment adjustment for CY 2020.

3. HH QRP

In section V. of this final rule with comment period, we are finalizing updates to the Home Health Quality Reporting Program (HH QRP) including: The removal of one quality measure, the adoption of two new quality measures, the modification of an existing measure, and a requirement for HHAs to report standardized patient assessment data. In section V.J. of this final rule, we are finalizing our proposal to re-designate our current HH QRP regulations in a different section of our regulations and to codify other current policies in that new regulatory section with one substantive change as well as a few technical edits. Finally, in section V.K. of the rule, we are not finalizing the removal of question 10 from all HHCAHPS Surveys (both mail surveys and telephone surveys).

4. Home Infusion Therapy

In section VI.A. of this final rule with comment period, we discuss the general background of home infusion therapy services and how that relates to the implementation of the new home infusion benefit in CY 2021. Section VI.B. of this final rule with comment period discusses the updates to the CY 2020 home infusion therapy services temporary transitional payment rates, in accordance with section 1834(u)(7) of the Act. In section VI.C. of this final rule with comment period, we are finalizing our proposal to add a new subpart P under the regulations at 42 CFR part 414 to incorporate conforming regulations text regarding conditions for payment for home infusion therapy services for CY 2021 and subsequent years. Subpart P includes beneficiary qualifications and plan of care requirements in accordance with section 1861(iii) of the Act. In section VI.D. of this final rule with comment period, we finalize payment provisions for the full implementation of the home infusion therapy benefit in CY 2021 upon expiration of the home infusion therapy services temporary transitional payments in CY 2020. The home infusion therapy services payment system is to be implemented starting in CY 2021, as mandated by section 5012 of the 21st Century Cures Act. The provisions in this section include payment categories, amounts, and required and optional payment adjustments. In section VI.E. of this final rule with comment period, we finalize the use of the Geographic Adjustment Factor (GAF) to wage adjust the home infusion therapy payment as required by section 1834(u)(1)(B)(i) of the Act. In section VI.F. of this final rule with comment period, we summarize comments received on the proposed rule regarding several topics for home infusion therapy services for CY 2021 such as: Optional payment adjustments, prior authorization, and high-cost outliers. In section VI.G. of this final rule with comment period, we discuss billing procedures for CY 2021 home infusion therapy services. Lastly, given the new permanent home infusion therapy benefit to be implemented beginning January 1, 2021, which includes payment for professional services, including nursing, for parenteral drugs administered intravenously or subcutaneously for a period of 15 minutes or more through a pump that is a covered item of DME; we are soliciting comments on options to enhance future efforts to improve policies related to coverage of eligible drugs for home infusion therapy. In response to stakeholder concerns regarding the limitations of the DME LCDs for External Infusion Pumps that preclude coverage to certain infused drugs, we seek comments on the criteria CMS could consider, within the scope of the DME benefit, to allow coverage of additional home infusion drugs.

C. Summary of Costs, Transfers, and Benefits

II. Overview of the Home Health Prospective Payment System

A. Statutory Background

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA) (Pub. L. 105-33, enacted August 5, 1997), significantly changed the way Medicare pays for Medicare home health services. Section 4603 of the BBA mandated the development of the HH PPS. Until the implementation of the HH PPS on October 1, 2000, HHAs received payment under a retrospective reimbursement system. Section 4603(a) of the BBA mandated the development of a HH PPS for all Medicare-covered home health services provided under a plan of care (POC) that were paid on a reasonable cost basis by adding section 1895 of the Act, entitled “Prospective Payment For Home Health Services.” Section 1895(b)(1) of the Act requires the Secretary to establish a HH PPS for all costs of home health services paid under Medicare. Section 1895(b)(2) of the Act required that, in defining a prospective payment amount, the Secretary will consider an appropriate unit of service and the number, type, and duration of visits provided within that unit, potential changes in the mix of services provided within that unit and their cost, and a general system design that provides for continued access to quality services.

Section 1895(b)(3)(A) of the Act required the following: (1) The computation of a standard prospective payment amount that includes all costs for HH services covered and paid for on a reasonable cost basis, and that such amounts be initially based on the most recent audited cost report data available to the Secretary (as of the effective date of the 2000 final rule), and (2) the standardized prospective payment amount be adjusted to account for the effects of case-mix and wage levels among HHAs.

Section 1895(b)(3)(B) of the Act requires the standard prospective payment amounts be annually updated by the home health applicable percentage increase. Section 1895(b)(4) of the Act governs the payment computation. Sections 1895(b)(4)(A)(i) and (b)(4)(A)(ii) of the Act require the standard prospective payment amount to be adjusted for case-mix and geographic differences in wage levels. Section 1895(b)(4)(B) of the Act requires the establishment of an appropriate case-mix change adjustment factor for significant variation in costs among different units of services.

Similarly, section 1895(b)(4)(C) of the Act requires the establishment of area wage adjustment factors that reflect the relative level of wages, and wage-related costs applicable to home health services furnished in a geographic area compared to the applicable national average level. Under section 1895(b)(4)(C) of the Act, the wage-adjustment factors used by the Secretary may be the factors used under section 1886(d)(3)(E) of the Act. Section 1895(b)(5) of the Act gives the Secretary the option to make additions or adjustments to the payment amount otherwise paid in the case of outliers due to unusual variations in the type or amount of medically necessary care. Section 3131(b)(2) of the Affordable Care Act revised section 1895(b)(5) of the Act so that total outlier payments in a given year would not exceed 2.5 percent of total payments projected or estimated. The provision also made permanent a 10 percent agency-level outlier payment cap.

In accordance with the statute, as amended by the BBA, we published a final rule in the July 3, 2000 Federal Register (65 FR 41128) to implement the HH PPS legislation. The July 2000 final rule established requirements for the new HH PPS for home health services as required by section 4603 of the BBA, as subsequently amended by section 5101 of the Omnibus Consolidated and Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 1999 (OCESAA), (Pub. L. 105-277, enacted October 21, 1998); and by sections 302, 305, and 306 of the Medicare, Medicaid, and SCHIP Balanced Budget Refinement Act of 1999, (BBRA) (Pub. L. 106-113, enacted November 29, 1999). The requirements include the implementation of a HH PPS for home health services, consolidated billing requirements, and a number of other related changes. The HH PPS described in that rule replaced the retrospective reasonable cost-based system that was used by Medicare for the payment of home health services under Part A and Part B. For a complete and full description of the HH PPS as required by the BBA, see the July 2000 HH PPS final rule (65 FR 41128 through 41214).

Section 5201(c) of the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (DRA) (Pub. L. 109-171, enacted February 8, 2006) added new section 1895(b)(3)(B)(v) to the Act, requiring HHAs to submit data for purposes of measuring health care quality, and linking the quality data submission to the annual applicable payment percentage increase. This data submission requirement is applicable for CY 2007 and each subsequent year. If an HHA does not submit quality data, the home health market basket percentage increase is reduced by 2 percentage points. In the November 9, 2006 Federal Register (71 FR 65935), we published a final rule to implement the pay-for-reporting requirement of the DRA, which was codified at § 484.225(h) and (i) in accordance with the statute. The pay-for-reporting requirement was implemented on January 1, 2007.

The Affordable Care Act made additional changes to the HH PPS. One of the changes in section 3131 of the Affordable Care Act is the amendment to section 421(a) of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA) (Pub. L. 108-173, enacted on December 8, 2003) as amended by section 5201(b) of the DRA. Section 421(a) of the MMA, as amended by section 3131 of the Affordable Care Act, requires that the Secretary increase, by 3 percent, the payment amount otherwise made under section 1895 of the Act, for HH services furnished in a rural area (as defined in section 1886(d)(2)(D) of the Act) with respect to episodes and visits ending on or after April 1, 2010, and before January 1, 2016.

Section 210 of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (Pub. L. 114-10) (MACRA) amended section 421(a) of the MMA to extend the 3 percent rural add-on payment for home health services provided in a rural area (as defined in section 1886(d)(2)(D) of the Act) through January 1, 2018. In addition, section 411(d) of MACRA amended section 1895(b)(3)(B) of the Act such that CY 2018 home health payments be updated by a 1 percent market basket increase. Section 50208(a)(1) of the BBA of 2018 again extended the 3 percent rural add-on through the end of 2018. In addition, this section of the BBA of 2018 made some important changes to the rural add-on for CYs 2019 through 2022 and these changes are discussed later in this final rule with comment period.

B. Current System for Payment of Home Health Services

Generally, Medicare currently makes payment under the HH PPS on the basis of a national, standardized 60-day episode payment rate that is adjusted for the applicable case-mix and wage index. The national, standardized 60-day episode rate includes the six home health disciplines (skilled nursing, home health aide, physical therapy, speech-language pathology, occupational therapy, and medical social services). Payment for non-routine supplies (NRS) is not part of the national, standardized 60-day episode rate, but is computed by multiplying the relative weight for a particular NRS severity level by the NRS conversion factor. Payment for durable medical equipment covered under the HH benefit is made outside the HH PPS payment system. To adjust for case-mix, the HH PPS uses a 153-category case-mix classification system to assign patients to a home health resource group (HHRG). The clinical severity level, functional severity level, and service utilization are computed from responses to selected data elements in the Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS) assessment instrument and are used to place the patient in a particular HHRG. Each HHRG has an associated case-mix weight which is used in calculating the payment for an episode. Therapy service use is measured by the number of therapy visits provided during the episode and can be categorized into nine visit level categories (or thresholds): 0 to 5; 6; 7 to 9; 10; 11 to 13; 14 to 15; 16 to 17; 18 to 19; and 20 or more visits.

For episodes with four or fewer visits, Medicare pays national per-visit rates based on the discipline(s) providing the services. An episode consisting of four or fewer visits within a 60-day period receives what is referred to as a low-utilization payment adjustment (LUPA). Medicare also adjusts the national standardized 60-day episode payment rate for certain intervening events that are subject to a partial episode payment adjustment (PEP adjustment). For certain cases that exceed a specific cost threshold, an outlier adjustment may also be available.

C. New Home Health Prospective Payment System for CY 2020 and Subsequent Years

In the CY 2019 HH PPS final rule with comment period (83 FR 56446), we finalized a new patient case-mix adjustment methodology, the Patient-Driven Groupings Model (PDGM), to shift the focus from volume of services to a more patient-driven model that relies on patient characteristics. For home health periods of care beginning on or after January 1, 2020, the PDGM uses timing, admission source, principal and other diagnoses, and functional impairment to case-mix adjust payments. The PDGM results in 432 unique case-mix groups. Low-utilization payment adjustments (LUPAs) will vary; instead of the current four visit threshold, each of the 432 case-mix groups has its own threshold to determine if a 30-day period of care would receive a LUPA. Additionally, non-routine supplies (NRS) are included in the base payment rate for the PDGM instead of being separately adjusted as in the current HH PPS. Also in the CY 2019 HH PPS final rule with comment period, we finalized a change in the unit of home health payment from 60-day episodes of care to 30-day periods of care, and eliminated the use of therapy thresholds used to adjust payments in accordance with section 51001 of the BBA of 2018. Thirty-day periods of care will be adjusted for outliers and partial episodes as applicable. Finally, for CYs 2020 through 2022, home health services provided to beneficiaries residing in rural counties will be increased based on rural county classification (high utilization; low population density; or all others) in accordance with section 50208 of the BBA of 2018.

D. Analysis of FY 2017 HHA Cost Report Data for 60-Day Episodes and 30-Day Periods

In the CY 2019 HH PPS proposed rule (83 FR 32348), we provided a summary of analysis on fiscal year (FY) 2016 HHA cost report data and how such data, if used, would impact our estimate of the percentage difference between Medicare payments and HHA costs. We stated in the CY 2019 HH PPS final rule with comment period (83 FR 56414) that we will continue to monitor the impacts due to policy changes and will provide the industry with periodic updates on our analysis in rulemaking and/or announcements on the HHA Center web page.

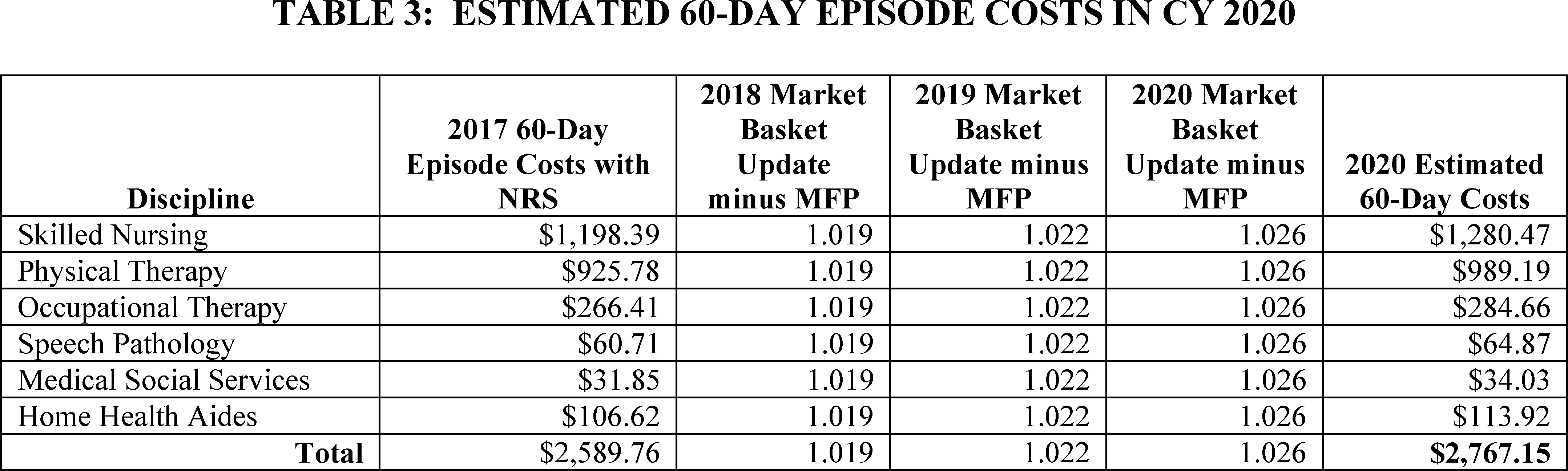

In this year's proposed rule (84 FR 34602), we examined FY 2017 HHA cost reports as this is the most recent and complete cost report data at the time of rulemaking. We include this analysis again in this final rule with comment period. We examined the estimated 60-day episode costs using FY 2017 cost reports and CY 2017 home health claims and the estimated costs for 60-day episodes by discipline and the total estimated cost for a 60-day episode for 2017 is shown in Table 2.

To estimate the costs for CY 2020, we updated the estimated 60-day episode costs with NRS by the home health market basket update, minus the multifactor productivity adjustment for CYs 2018 and 2019. In the proposed rule, we estimated the CY 2020 costs by using the home health market basket update of 1.5 percent as required by the BBA of 2018. However, for this final rule with comment period, we believe that we should be consistent with the estimation of cost calculations for purposes of analyzing the payment adequacy. This would warrant the same approach for estimating CY 2020 costs as was used for CYs 2018 and 2019. Therefore, for this final rule with comment period, we calculated the estimated CY 2020 60-day episode costs and 30-day period costs by applying each year's market basket update minus the multifactor productivity factor for that year. For CY 2020, based on IHS Global Inc. 2019 q3 forecast, the home health market basket update is forecasted to be 2.9 percent; the MFP adjustment is forecasted to be 0.3 percent resulting in a forecasted MFP-adjusted home health market basket update of 2.6 percent. The estimated costs for 60-day episodes by discipline and the total estimated cost for a 60-day episode for CY 2020 is shown in Table 3.

The CY 2020 60-day episode payment will be $3,220.79, approximately 16 percent more than the estimated CY 2020 60-day episode cost of $2,767.15.

Next, we also looked at the estimated costs for 30-day periods of care in 2017 using FY 2017 cost reports and CY 2017 claims. Thirty-day periods were simulated from 60-day episodes and we excluded low-utilization payment adjusted episodes and partial-episode-payment adjusted episodes. The 30-day periods were linked to OASIS assessments and covered the 60-day episodes ending in CY 2017. The estimated costs for 30-day periods by discipline and the total estimated cost for a 30-day period for 2017 is shown in Table 4.

Using the same approach as calculating the estimated CY 2020 60-day episode costs, we updated the estimated 30-day period costs with NRS by the home health market basket update, minus the multifactor productivity adjustment for CYs 2018 2019, and 2020. The estimated costs for 30-day periods by discipline and the total estimated cost for a 30-day period for CY 2020 is shown in Table 5.

The estimated, budget-neutral 30-day payment for CY 2020 is, $1,824.99 as described in section III.E. of this final rule with comment period. Updating this amount by the CY 2020 home health market basket update of 1.5 percent and the wage index budget neutrality factor results in an estimated CY 2020 30-day payment amount of $1,864.03 (as described in section III.B. of this final rule with comment period) approximately 16 percent more than the estimated CY 2020 30-day period cost of $1,608.82. After implementation of the 30-day unit of payment and the PDGM in CY 2020, we will continue to analyze the costs by discipline as well as the overall cost for a 30-day period of care to determine the effects, if any, of these changes.

III. Payment Under the Home Health Prospective Payment System (HH PPS)

A. Implementation of the Patient-Driven Groupings Model (PDGM) for CY 2020

1. Background and Legislative History

In the CY 2019 HH PPS final rule with comment period (83 FR 56406), we finalized provisions to implement changes mandated by the BBA of 2018 for CY 2020, which included a change in the unit of payment from a 60-day episode of care to a 30-day period of care, as required by section 51001(a)(1)(B), and the elimination of therapy thresholds used for adjusting home health payment, as required by section 51001(a)(3)(B). In order to eliminate the use of therapy thresholds in adjusting payment under the HH PPS, we finalized an alternative case mix-adjustment methodology, known as the Patient-Driven Groupings Model (PDGM), to be implemented for home health periods of care beginning on or after January 1, 2020.

In regard to the 30-day unit of payment, section 51001(a)(1) of the BBA of 2018 amended section 1895(b)(2) of the Act by adding a new subparagraph (B) to require the Secretary to apply a 30-day unit of service, effective January 1, 2020. Section 51001(a)(2)(A) of the BBA of 2018 added a new subclause (iv) under section 1895(b)(3)(A) of the Act, requiring the Secretary to calculate a standard prospective payment amount (or amounts) for 30-day units of service, furnished that end during the 12-month period beginning January 1, 2020, in a budget neutral manner, such that estimated aggregate expenditures under the HH PPS during CY 2020 are equal to the estimated aggregate expenditures that otherwise would have been made under the HH PPS during CY 2020 in the absence of the change to a 30-day unit of service. Section 1895(b)(3)(A)(iv) of the Act requires that the calculation of the standard prospective payment amount (or amounts) for CY 2020 be made before the application of the annual update to the standard prospective payment amount as required by section 1895(b)(3)(B) of the Act.

Section 1895(b)(3)(A)(iv) of the Act additionally requires that in calculating the standard prospective payment amount (or amounts), the Secretary must make assumptions about behavior changes that could occur as a result of the implementation of the 30-day unit of service under section 1895(b)(2)(B) of the Act and case-mix adjustment factors established under section 1895(b)(4)(B) of the Act. Section 1895(b)(3)(A)(iv) of the Act further requires the Secretary to provide a description of the behavior assumptions made in notice and comment rulemaking. CMS finalized these behavior assumptions in the CY 2019 HH PPS final rule with comment period (83 FR 56461) and these assumptions are further described in section III.B. of this final rule with comment period.

Section 51001(a)(2)(B) of the BBA of 2018 also added a new subparagraph (D) to section 1895(b)(3) of the Act. Section 1895(b)(3)(D)(i) of the Act requires the Secretary to annually determine the impact of differences between assumed behavior changes as described in section 1895(b)(3)(A)(iv) of the Act, and actual behavior changes on estimated aggregate expenditures under the HH PPS with respect to years beginning with 2020 and ending with 2026. Section 1895(b)(3)(D)(ii) of the Act requires the Secretary, at a time and in a manner determined appropriate, through notice and comment rulemaking, to provide for one or more permanent increases or decreases to the standard prospective payment amount (or amounts) for applicable years, on a prospective basis, to offset for such increases or decreases in estimated aggregate expenditures, as determined under section 1895(b)(3)(D)(i) of the Act. Additionally, 1895(b)(3)(D)(iii) of the Act requires the Secretary, at a time and in a manner determined appropriate, through notice and comment rulemaking, to provide for one or more temporary increases or decreases, based on retrospective behavior, to the payment amount for a unit of home health services for applicable years, on a prospective basis, to offset for such increases or decreases in estimated aggregate expenditures, as determined under section 1895(b)(3)(D)(i) of the Act. Such a temporary increase or decrease shall apply only with respect to the year for which such temporary increase or decrease is made, and the Secretary shall not take into account such a temporary increase or decrease in computing the payment amount for a unit of home health services for a subsequent year. And finally, section 51001(a)(3) of the BBA of 2018 amends section 1895(b)(4)(B) of the Act by adding a new clause (ii) to require the Secretary to eliminate the use of therapy thresholds in the case-mix system for CY 2020 and subsequent years.

2. Overview and CY 2020 Implementation of the PDGM

To better align payment with patient care needs and better ensure that clinically complex and ill beneficiaries have adequate access to home health care, in the CY 2019 HH PPS final rule with comment period (83 FR 56406), we finalized case-mix methodology refinements through the PDGM for home health periods of care beginning on or after January 1, 2020. We believe that the PDGM case-mix methodology better aligns payment with patient care needs and is a patient-centered model that groups periods of care in a manner consistent with how clinicians differentiate between patients and the primary reason for needing home health care. This final rule with comment period effectuates the requirements for the implementation of the PDGM, as well as finalizes updates to the PDGM case-mix weights and payment rates, which would be effective on January 1, 2020. The PDGM and a change to a 30-day unit of payment were finalized in the CY 2019 HH PPS final rule with comment period (83 FR 56406) and, as such, there were no new policy proposals in the CY 2020 home health proposed rule on the structure of the PDGM or the change to a 30-day unit of payment. However, there were proposals related to the split-percentage payments upon implementation of the PDGM and the 30-day unit of payment as described in section III.G. of this final rule with comment period.

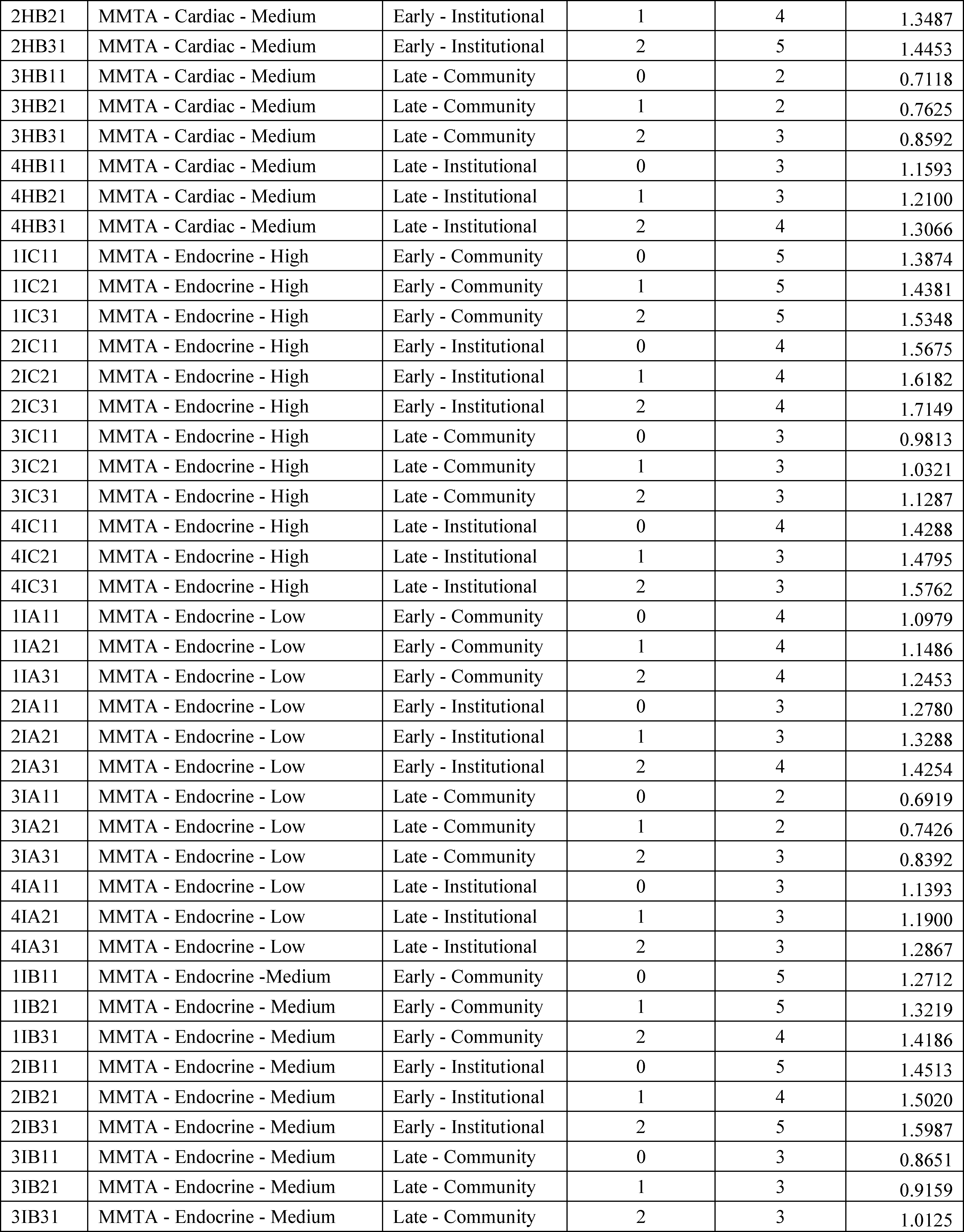

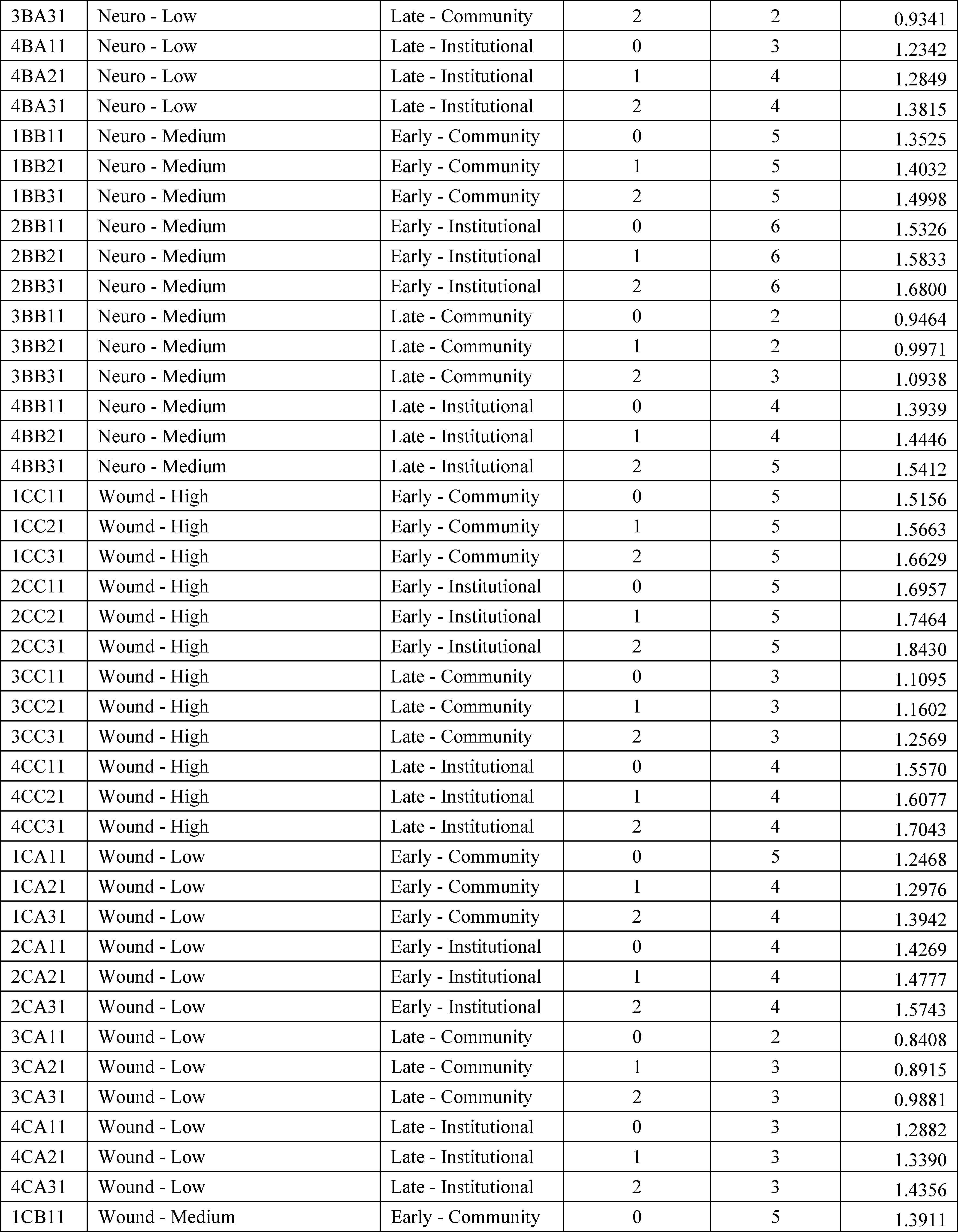

The PDGM uses 30-day periods of care rather than 60-day episodes of care as the unit of payment, as required by section 51001(a)(1)(B) of the BBA of 2018; eliminates the use of the number of therapy visits provided to determine payment, as required by section 51001(a)(3)(B) of the BBA of 2018; and relies more heavily on clinical characteristics and other patient information (for example, diagnosis, functional level, comorbid conditions, admission source) to place patients into clinically meaningful payment categories. A national, standardized 30-day period payment amount, as described in section III.E. of this final rule with comment period, will be adjusted by the case-mix weights as determined by the variables in the PDGM. Payment for non-routine supplies (NRS) is now included in the national, standardized 30-day payment amount. In total, there are 432 different payment groups in the PDGM. These 432 Home Health Resource Groups (HHRGs) represent the different payment groups based on five main case-mix variables under the PDGM, as shown in Figure B1, and subsequently described in more detail throughout this section.

Under this new case-mix methodology, case-mix weights are generated for each of the different PDGM payment groups by regressing resource use for each of the five categories listed in this section of this final rule with comment period (timing, admission source, clinical grouping, functional impairment level, and comorbidity adjustment) using a fixed effects model. Annually recalibrating the PDGM case-mix weights ensures that the case-mix weights reflect the most recent utilization data at the time of annual rulemaking. The final CY 2020 PDGM case-mix weights are listed in section III.D. of this final rule with comment period.

a. Timing

Under the PDGM, 30-day periods of care will be classified as “early” or “late” depending on when they occur within a sequence of 30-day periods. Under the PDGM, the first 30-day period of care will be classified as early and all subsequent 30-day periods of care in the sequence (second or later) will be classified as late. A 30-day period will not be considered early unless there is a gap of more than 60 days between the end of one period of care and the start of another. Information regarding the timing of a 30-day period of care will come from Medicare home health claims data and not the OASIS assessment to determine if a 30-day period of care is “early” or “late”. While the PDGM case-mix adjustment is applied to each 30-day period of care, other home health requirements will continue on a 60-day basis. Specifically, certifications and re-certifications continue on a 60-day basis and the comprehensive assessment will still be completed within 5 days of the start of care date and completed no less frequently than during the last 5 days of every 60 days beginning with the start of care date, as currently required by § 484.55, “Condition of participation: Comprehensive assessment of patients.”

b. Admission Source

Each 30-day period of care will also be classified into one of two admission source categories—community or institutional—depending on what healthcare setting was utilized in the 14 days prior to home health. Thirty-day periods of care for beneficiaries with any inpatient acute care hospitalizations, inpatient psychiatric facility (IPF) stays, skilled nursing facility (SNF) stays, inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF) stays, or long-term care hospital (LTCH) stays within 14-days prior to a home health admission will be designated as institutional admissions.

The institutional admission source category will also include patients that had an acute care hospital stay during a previous 30-day period of care and within 14 days prior to the subsequent, contiguous 30-day period of care and for which the patient was not discharged from home health and readmitted (that is, the “admission date” and “from date” for the subsequent 30-day period of care do not match), as we acknowledge that HHAs have discretion as to whether they discharge the patient due to a hospitalization and then readmit the patient after hospital discharge. However, we will not categorize post-acute care stays, meaning SNF, IRF, LTCH, or IPF stays, that occur during a previous 30-day period of care and within 14 days of a subsequent, contiguous 30-day period of care as institutional (that is, the “admission date” and “from date” for the subsequent 30-day period of care do not match), as we would expect the HHA to discharge the patient if the patient required post-acute care in a different setting, or inpatient psychiatric care, and then readmit the patient, if necessary, after discharge from such setting. All other 30-day periods of care would be designated as community admissions.

Information from the Medicare claims processing system will determine the appropriate admission source for final claim payment. The OASIS assessment will not be utilized in evaluating for admission source information. We believe that obtaining this information from the Medicare claims processing system, rather than as reported on the OASIS, is a more accurate way to determine admission source information as HHAs may be unaware of an acute or post-acute care stay prior to home health admission. While HHAs can report an occurrence code on submitted claims to indicate the admission source, obtaining this information from the Medicare claims processing system allows CMS the opportunity and flexibility to verify the source of the admission and correct any improper payments as deemed appropriate. When the Medicare claims processing system receives a Medicare home health claim, the systems will check for the presence of a Medicare acute or post-acute care claim for an institutional stay. If such an institutional claim is found, and the institutional claim occurred within 14 days of the home health admission, our systems will trigger an automatic adjustment to the corresponding HH claim to the appropriate institutional category. Similarly, when the Medicare claims processing system receives a Medicare acute or post-acute care claim for an institutional stay, the systems will check for the presence of a HH claim with a community admission source payment group. If such HH claim is found, and the institutional stay occurred within 14 days prior to the home health admission, our systems will trigger an automatic adjustment of the HH claim to the appropriate institutional category. This process may occur any time within the 12-month timely filing period for the acute or post-acute claim.

However, situations in which the HHA has information about the acute or post-acute care stay, HHAs will be allowed to manually indicate on Medicare home health claims that an institutional admission source had occurred prior to the processing of an acute/post-acute Medicare claim, in order to receive higher payment associated with the institutional admission source. This will be done through the reporting of one of two admission source occurrence codes on home health claims—

- Occurrence Code 61: to indicate an acute care hospital discharge within 14 days prior to the “From Date” of any home health claim; or

- Occurrence Code 62: to indicate a SNF, IRF, LTCH, or IPF discharge with 14 days prior to the “Admission Date” of the first home health claim.

If the HHA does not include an occurrence code on the HH claim to indicate that that the home health patient had a previous acute or post-acute care stay, the period of care will be categorized as a community admission source. However, if later a Medicare acute or post-acute care claim for an institutional stay occurring within 14 days of the home health admission is submitted within the timely filing deadline and processed by the Medicare systems, the HH claim will be automatically adjusted as an institutional admission and the appropriate payment modifications will be made. For purposes of a Request for Anticipated Payment (RAP), only the final claim will be adjusted to reflect the admission source. More information regarding the admission source reporting requirements for RAP and claims submission can be found in Change Request 11081, “Home Health (HH) Patient-Drive Groupings Model (PDGM)-Split Implementation”.[1] Accordingly, the Medicare Claims Processing Manual, chapter 10,[2] has been updated to reflect all of the claims processing changes associated with implementation of the PDGM.

c. Clinical Groupings

Each 30-day period of care will be grouped into one of 12 clinical groups which describe the primary reason for which patients are receiving home health services under the Medicare home health benefit. The clinical grouping is based on the principal diagnosis reported on home health claims. The 12 clinical groups are listed and described in Table 6.

It is possible for the principal diagnosis to change between the first and second 30-day period of care and the claim for the second 30-day period of care would reflect the new principal diagnosis. HHAs would not change the claim for the first 30-day period. However, a change in the principal diagnosis does not necessarily mean that an “other follow-up” OASIS assessment (RFA 05) would need to be completed just to make the diagnoses match. However, if a patient experienced a significant change in condition before the start of a subsequent, contiguous 30-day period of care, for example due to a fall, in accordance with § 484.55(d)(1)(ii) the HHA is required to update the comprehensive assessment. The Home Health Agency Interpretive Guidelines [3] for § 484.55(d), state that a marked improvement or worsening of a patient's condition, which changes, and was not anticipated in, the patient's plan of care would be considered a “major decline or improvement in the patient's health status” that would warrant update and revision of the comprehensive assessment.[4] Additionally, in accordance with § 484.60, the total plan of care must be reviewed and revised by the physician who is responsible for the home health plan of care and the HHA as frequently as the patient's condition or needs require, but no less frequently than once every 60 days, beginning with the start of care date.

In the event of a significant change of condition warranting an updated comprehensive assessment, an “other follow-up assessment” (RFA 05) would be submitted before the start of a subsequent, contiguous 30-day period, which may reflect a change in the functional impairment level and the second 30-day claim would be grouped into its appropriate case-mix group accordingly. An “other follow-up assessment” is a comprehensive assessment conducted due to a major decline or improvement in patient's health status occurring at a time other than during the last 5 days of the episode. This assessment is done to re-evaluate the patient's condition, allowing revision to the patient's care plan as appropriate. The “Outcome and Assessment Information Set OASIS-D Guidance Manual,” effective January 1, 2019, provides more detailed guidance for the completion of an “other follow-up” assessment.[5] In this respect, two 30-day periods can have two different case-mix groups to reflect any changes in patient condition. HHAs must be sure to update the assessment completion date on the second 30-day claim if a follow-up assessment changes the case-mix group to ensure the claim can be matched to the follow-up assessment. HHAs can submit an adjustment to the original claim submitted if an assessment was completed before the start of the second 30-day period, but was received after the claim was submitted and if the assessment items would change the payment grouping.

HHAs would determine whether or not to complete a follow-up OASIS assessment for a second 30-day period of care depending on the individual's clinical circumstances. For example, if the only change from the first 30-day period and the second 30-day period is a change to the principal diagnosis and there is no change in the patient's function, the HHA may determine it is not necessary to complete a follow-up assessment. Therefore, the expectation is that HHAs would determine whether an “other follow-up” assessment is required based on the individual's overall condition, the effects of the change on the overall home health plan of care, and in accordance with the home health CoPs,[6] interpretive guidelines, and the OASIS D Guidance Manual instructions, as previously noted.

For case-mix adjustment purposes, the principal diagnosis reported on the home health claim will determine the clinical group for each 30-day period of care. Currently, billing instructions state that the principal diagnosis on the OASIS must also be the principal diagnosis on the final claim; however, we will update our billing instructions to clarify that there will be no need for the HHA to complete an “other follow-up” assessment (an RFA 05) just to make the diagnoses match. Therefore, for claim “From” dates on or after January 1, 2020, the ICD-10-CM code and principal diagnosis used for payment grouping will be from the claim rather than the OASIS. As a result, the claim and OASIS diagnosis codes will no longer be expected to match in all cases. Additional claims processing guidance, including the role of the OASIS item set is included in the Medicare Claims Processing Manual, chapter 10.

While these clinical groups represent the primary reason for home health services during a 30-day period of care, this does not mean that they represent the only reason for home health services. While there are clinical groups where the primary reason for home health services is for therapy (for example, Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation) and other clinical groups where the primary reason for home health services is for nursing (for example, Complex Nursing Interventions), home health remains a multidisciplinary benefit and payment is bundled to cover all necessary home health services identified on the individualized home health plan of care. Therefore, regardless of the clinical group assignment, HHAs are required, in accordance with the home health CoPs at § 484.60(a)(2), to ensure that the individualized home health plan of care addresses all care needs, including the disciplines to provide such care. Under the PDGM, the clinical group is just one variable in the overall case-mix adjustment for a home health period of care.

Finally, to accompany this final rule with comment period, we updated the Interactive Grouper Tool posted on both the HHA Center web page (https://www.cms.gov/center/provider-type/home-health-agency-hha-center.html) and the PDGM web page (https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/HomeHealthPPS/HH-PDGM.html). This Interactive Grouper Tool includes all of the ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes used in the PDGM and may be used by HHAs to generate PDGM case-mix weights for their patient census. This tool is for informational and illustrative purposes only. This Interactive Grouper Tool has been provided to assist HHAs in understanding the effects of the transition to the PDGM and will not be updated on an annual basis after CY 2020 as HHAs will have the opportunity download the HH PPS Grouper annually. The final grouper for CY 2020 will be posted with this final rule with comment period and can be found on the following website: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/HomeHealthPPS/CaseMixGrouperSoftware.html. Additionally, HHAs can also request a Home Health Claims-OASIS Limited Data Set (LDS) to accompany the CY 2020 HH PPS final rule with comment period to support HHAs in evaluating the effects of the PDGM. The Home Health Claims-OASIS LDS file can be requested by following the instructions on the CMS Limited Data Set (LDS) Files website: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Files-for-Order/Data-Disclosures-Data-Agreements/DUA_-_NewLDS.html.

d. Functional Impairment Level

Under the PDGM, each 30-day period of care will be placed into one of three functional impairment levels, low, medium, or high, based on responses to certain OASIS functional items as listed in Table 7.

Responses to these OASIS items are grouped together into response categories with similar resource use and each response category has associated points. A more detailed description as to how these response categories were established can be found in the technical report, “Overview of the Home Health Groupings Model” posted on the Home Health Center web page.[7] The sum of these points' results in a functional impairment level score used to group 30-day periods of care into a functional impairment level with similar resource use. The scores associated with the functional impairment levels vary by clinical group to account for differences in resource utilization. For CY 2020, we used CY 2018 claims data to update the functional points and functional impairment levels by clinical group. The updated OASIS functional points table and the table of functional impairment levels by clinical group for CY 2020 are listed in Tables 8 and 9 respectively. For ease of use, instead of listing the response categories and the associated points (as shown in Table 28 in the CY 2019 HH PPS final rule with comment period (83 FR 56478), we have reformatted the OASIS Functional Item Response Points (Table 8 to identify how the OASIS functional items used for the functional impairment level are assigned points under the PDGM. In this CY 2020 HH PPS final rule with comment period, we updated the points for the OASIS functional item response categories and the functional impairment levels by clinical group using the most recent, available claims data.

The functional impairment level will remain the same for the first and second 30-day periods of care unless there has been a significant change in condition which warranted an “other follow-up” assessment prior to the second 30-day period of care. For each 30-day period of care, the Medicare claims processing system will look for the most recent OASIS assessment based on the claims “from date.” The finalized CY 2020 functional points table and the functional impairment level thresholds table are posted on the HHA Center web page as well as on the PDGM web page.

e. Comorbidity Adjustment

Thirty-day periods will receive a comorbidity adjustment category based on the presence of certain secondary diagnoses reported on home health claims. These diagnoses are based on a home-health specific list of clinically and statistically significant secondary diagnosis subgroups with similar resource use, meaning the diagnoses have at least as high as the median resource use and are reported in more than 0.1 percent of 30-day periods of care. Home health 30-day periods of care can receive a comorbidity adjustment under the following circumstances:

Low comorbidity adjustment: There is a reported secondary diagnosis on the home health-specific comorbidity subgroup list that is associated with higher resource use.

High comorbidity adjustment: There are two or more secondary diagnoses on the home health-specific comorbidity subgroup interaction list that are associated with higher resource use when both are reported together compared to if they were reported separately. That is, the two diagnoses may interact with one another, resulting in higher resource use.

No comorbidity adjustment: A 30-day period of care will receive no comorbidity adjustment if no secondary diagnoses exist or none meet the criteria for a low or high comorbidity adjustment.

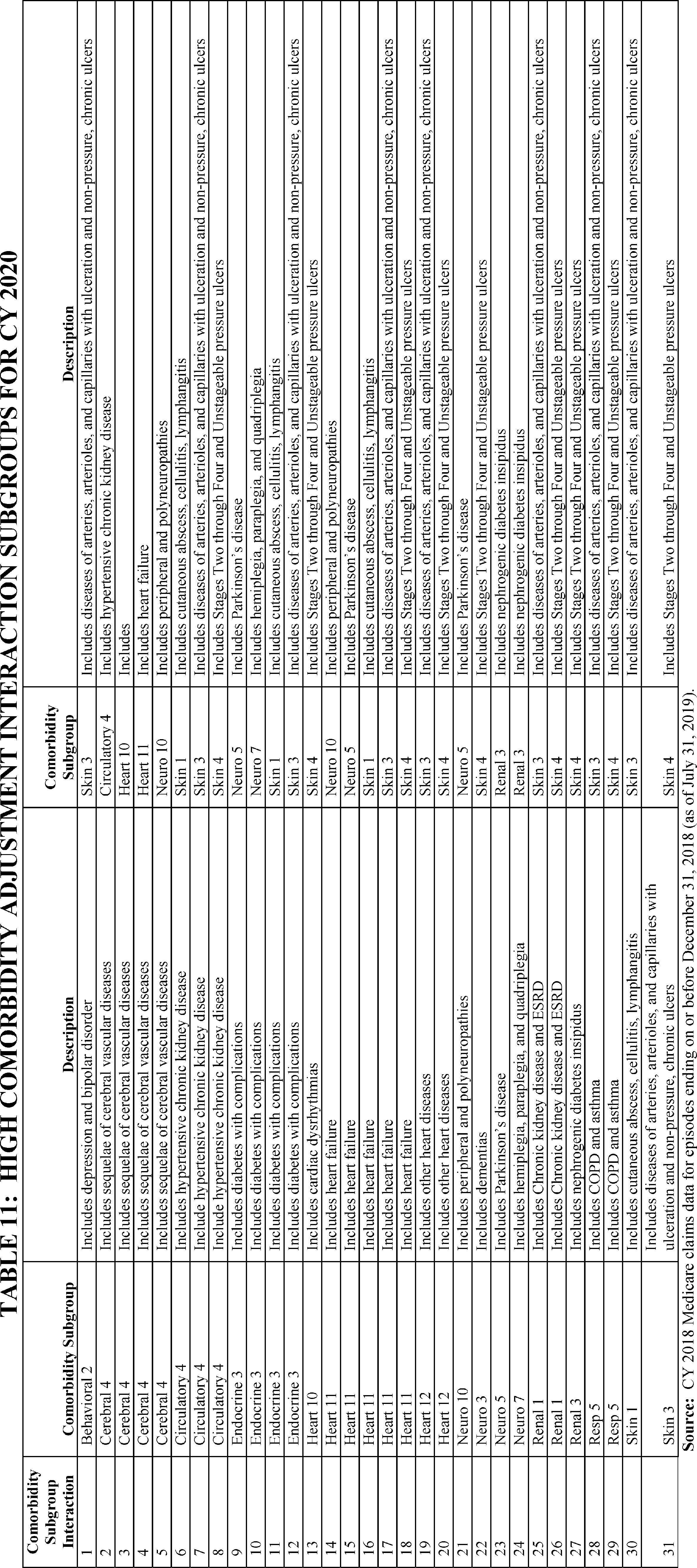

For CY 2020, there are 13 low comorbidity adjustment subgroups as identified in Table 10 and 31 high comorbidity adjustment interaction subgroups as identified in Table 11.

A 30-day period of care can have a low comorbidity adjustment or a high comorbidity adjustment, but not both. A 30-day period of care can receive only one low comorbidity adjustment regardless of the number of secondary diagnoses reported on the home health claim that fell into one of the individual comorbidity subgroups or one high comorbidity adjustment regardless of the number of comorbidity group interactions, as applicable. The low comorbidity adjustment amount will be the same across the subgroups and the high comorbidity adjustment will be the same across the subgroup interactions. The finalized CY 2020 low comorbidity adjustment subgroups and the high comorbidity adjustment interaction subgroups including those diagnoses within each of these comorbidity adjustments are posted on the HHA Center web page as well as on the PDGM web page.

While we did not solicit comments on the PDGM as it was finalized in the CY 2019 HH PPS final rule with comment period (83 FR 56406), we did receive 179 comments on various components of the finalized PDGM from home health agencies, industry associations, as well as individuals. We received a few general comments on the PDGM as a whole. A few comments were received on the admission source case-mix variable, elimination of therapy thresholds, and the comorbidity adjustment; however, the majority of these comments were specific ICD 10-CM code requests to include certain previously excluded diagnosis codes as part of the clinical grouping variable or to move specific diagnosis codes from one clinical group to another. These comments and our responses are summarized in this section of this final rule with comment period.

1. General PDGM Comments

Comment: Several commenters stated they are very encouraged by CMS's efforts to develop a valid and reliable case mix adjustment model that relies on patient characteristics rather than resource use to determine the amount of payment in individual service claims. However, these commenters expressed concern that the PDGM could create financial incentives for home health agencies to under-supply needed care through inappropriate early discharge, improperly limiting the number of visits or types of services provided, or discouraging serving individuals with longer-term needs and people without a prior institutional stay. A commenter recommended that CMS monitor these issues and quality of care during initial implementation of the PDGM in ways that will allow CMS to quickly understand and address emerging problems affecting the provision of home health services. This commenter also suggested that CMS educate home health agencies as well as beneficiaries and their family caregivers about the need for beneficiaries to receive high-quality home health care that meets each Medicare beneficiary's unique needs. Other suggestions included requiring agencies to provide clear, accurate information about what Medicare covers and beneficiary appeal rights and updating CMS educational materials for beneficiaries to assist in this effort. Another commenter urged CMS to be transparent about its education budget and include information about the different mechanisms it will use for the education of providers, beneficiaries, and their family caregivers (as appropriate).

Response: We appreciate commenter support of a case-mix system based on patient-characteristics and other clinical information, rather than one based on the volume of services provided. We agree that this is a more accurate way to align payment with the cost of providing care. However, we recognize stakeholder concerns about possible perverse financial incentives that could arise as a result of transitioning to a new case-mix adjustment methodology and a change in the unit of payment. We reiterate that we expect the provision of services to be made to best meet the patient's care needs and in accordance with the home health CoPs at § 484.60 which sets forth the requirements for the content of the individualized home health plan of care which includes the types of services, supplies, and equipment required; the frequency and duration of visits to be made; as well as patient and caregiver education and training to facilitate timely discharge. Therefore, we do not expect HHAs to under-supply care or services; reduce the number of visits in response to payment; or inappropriately discharge a patient receiving Medicare home health services as these would be violations of the CoPs and could also subject HHAs to program integrity measures.

We also note that the home health CoPs at § 484.50(c) set forth patient rights, which include the patient's right to be involved in the plan of care, the right to be informed of any changes to the plan of care, as well as expected coverage, and possible beneficiary financial liability. Therefore, HHAs are already tasked with informing beneficiaries as to their rights and coverage under the Medicare home health benefit. Moreover, CMS does routinely update its public materials to ensure relevant stakeholders are informed of any policy, coverage, or payment changes. This includes updates to the Medicare Benefit Policy Manual, the “Medicare and You” Handbook, “Medicare's Home Health Benefit” booklet, and MLN Matters® articles on various aspects of the home health benefit. As with any policy, coverage, or payment change, we will update the necessary public information to ensure full transparency and to provide ample resources for beneficiaries and their families, as well as for home health agencies. The goal of the PDGM is to more accurately align home health payment with patient needs. We note that each individual policy change does not have a corresponding individual educational budget connected with its implementation; therefore this is not information we can provide. We acknowledge that the change to a new case-mix system may have unintended consequences through shifts in home health practices. However, in the CY 2020 HH PPS proposed rule, we stated that we expect the provision of services to be made to best meet the patient's care needs and in accordance with existing regulations. We also noted that we would monitor any changes in utilization patterns, beneficiary impact, and provider behavior to see if any refinements to the PDGM would be warranted, or if any concerns are identified that may signal the need for appropriate program integrity measures.

Comment: A commenter stated that under the current HH PPS, HHAs' costs are “frontloaded” and incurred regardless of whether a second 30-day period occurs within a 60-day episode. This commenter stated that CMS should account for these costs and allocate payment weights more toward the first 30-day period in each 60-day episode to ensure that payments are accurately aligned with resource use. Commenters express several concerns with the use of cost report data rather than Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) wage data to account for the cost of therapy services; thus, commenters recommend CMS use BLS wage-weighted minutes instead of the approach finalized in the CY 2019 final rule with comment period.

Response: We note that we provided detailed analysis on the estimated costs of 30-day periods of care using a cost-per-minute plus non-routine supply (CPM + NRS) approach in the CY 2019 HH PPS proposed rule (83 FR 32387). We also provided analysis on the average resource use by timing where early 30-day periods have higher resource use that later 30-day periods (83 FR 32392). Likewise, in the CY 2019 HH PPS final rule with comment period (83 FR 56471), we finalized the admission source case-mix variable under the PDGM where “early” 30-day periods of care receive a higher payment than “late” 30-day periods of care. Commenters supported this payment differential as it more accurately reflects HHA costs that are typically higher during the first 30-day period of care, compared to later 30-day periods of care.

When we finalized the CPM+NRS approach to calculating the costs of care in the CY 2019 HH PPS final rule with comment period, we stated that we believe that the use of HHA Medicare cost reports better reflects changes in utilization, provider payments, and supply amongst Medicare-certified HHAs that occur over time. Under the Wage-Weighted Minutes of Care (WWMC) approach, using the BLS average hourly wage rates for the entire home health care service industry does not reflect changes in Medicare home health utilization that impact costs, such as the allocation of overhead costs when Medicare home health visit patterns change. Using data from HHA Medicare cost reports better represents the total costs incurred during a 30-day period (including, but not limited to, direct patient care contract labor, overhead, and transportation costs), while the WWMC method provides an estimate of only the labor costs (wage and fringe benefit costs) related to direct patient care from patient visits that are incurred during a 30-day period.

Comment: A commenter suggested an additional alternative to consider regarding the implementation of the PDGM. Specifically, this commenter suggested a potential pilot program to test not only the PDGM but possibly the PDPM payment system for skilled nursing facilities to consider some form of a post-acute bundle with shared savings.

Response: We appreciate the commenter's suggestions for innovative ways to improve the health care system and payment models. However, we note that the change in the unit of payment and the case-mix methodology is mandated by the BBA of 2018, as such we are required to implement such changes beginning on January 1, 2020.

2. Admission Source

Comment: A commenter stated that it appears counterintuitive to have a different reimbursement for community versus institutional admission source stating that the goal of home health care is to keep the patients out of the hospital. A commenter expressed concern that even though the application of an admission source measure may seem warranted given data demonstrating different resource use, doing so may incentivize agencies to give priority to post-acute patients over those who are admitted from the community. This commenter stated that the financial impact of the PDGM admission source measure also highlights the inherent weakness of all the other PDGM measures. A few commenters supported the admission source as an indicator of predicted home health resource use.

Response: We agree that the provision of home health services may play an important role in keeping patient's out of the hospital, whether the patient is admitted to home health from an institutional source or from the community. However, the payment adjustments associated with the PDGM case-mix variables are based on the cost of providing care. As described in the CY 2018 HH PPS proposed rule (82 FR 35311), our analytic findings demonstrate that institutional admissions have significantly higher average resource use when compared with community admissions, which ultimately led to the inclusion of the admission source category within the framework of the alternative case-mix adjustment methodology refinements. Additionally, in the CY 2018 HH PPS proposed rule (82 FR 35309), we stated that in our review of related scholarly research, we found that beneficiaries admitted directly or recently from an institutional setting (acute or post-acute care (PAC)) tend to have different care needs and higher resource use than those admitted from the community, thus indicating the need for differentiated payment amounts. Furthermore, in the CY 2018 proposed rule, we provided detailed analysis and research to support the inclusion of an admission source category for case-mix adjustment. We continue to believe that having a case-mix variable accounting for admission source is clinically appropriate, will address the more intensive care needs of those admitted to home health from an institutional setting, and will more accurately align payment with the cost of providing home health care.

To address concerns that the admission source variable may create the incentive to favor institutional admission sources, we fully intend to monitor provider behavior in response to the new PDGM. As we receive and evaluate new data related to the provision of Medicare home health care under the PDGM, we will reassess the appropriateness of the payment levels for all of the case-mix variables, including admission source, to determine if HHAs are inappropriately changing their behavior to favor institutional admission sources over community. Additionally, we will share any concerning behavior or patterns with the Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) and other program integrity contractors, if warranted. We plan to monitor and identify any variations in the patterns of care provided to home health patients, including both increased and decreased provision of care to Medicare beneficiaries. We remind stakeholders that the purpose of case-mix adjustment is to align payment with the costs of providing care. As such, certain case-mix variables may have a more significant impact on the payment adjustment than others. However, the case-mix variables in the PDGM work in tandem to fully capture patient characteristics that translate to higher resource needs. The overall payment for a home health period of care under the PDGM is determined by the cumulative effect of all of the variables used in the case-mix adjustments. Ultimately, the goal of the PDGM is to provide more accurate payment based on the identified resource use of different patient groups.

3. Therapy Thresholds

Comment: A few commenters disagreed with the elimination of the therapy thresholds and expressed concern that the PDGM design will have a negative impact on patients who need therapy services and the HHAs that provide it. A commenter stated that therapy services are extraordinarily valuable in the care of Medicare home health beneficiaries and should be supported to the greatest degree possible. Another commenter suggested elimination of the 30-day therapy reassessment requirement stating this would duplicative and unnecessary under PDGM, given that therapy visits are no longer a payment driver, and that all visits must continue to demonstrate a skilled need, independent of a formal reassessment. Many commenters urge CMS to monitor the effects of PDGM and the implications on therapy utilization due to concerns therapy would be underutilized, which could result in beneficiaries going to inpatient settings rather than receiving care at home. Some commenters recommend further analysis to compare utilization of therapy revenue codes under the PPS and PDGM. In addition, commenters encourage CMS to use the survey process to ensure that beneficiaries continue to receive the appropriate level of therapy that were medically necessary in order to treat or manage the condition.

Response: We agree that therapy remains a valuable service for Medicare home health beneficiaries. In response to the CY 2018 and 2019 HH PPS proposed rules, the majority of commenters agreed that the elimination of therapy thresholds was appropriate because of the financial incentive to overprovide therapy services. While the functional impairment level adjustment in the PDGM is not meant to be a direct proxy for the therapy thresholds, the PDGM has other case-mix variables to adjust payment for those patients requiring multiple therapy disciplines or those chronically ill patients with significant functional impairment. We believe that also accounting for timing, source of admission, clinical group (meaning the primary reason the patient requires home health services), and the presence of comorbidities will provide the necessary adjustments to payment to ensure that care needs are met based on actual patient characteristics. Furthermore, services are to be provided in accordance with the home health plan of care established and periodically reviewed by the certifying physician. Therefore, we expect that home health agencies will continue to provide needed therapy services in accordance with the CoPs at § 484.60, which state that the individualized plan of care must specify the care and services necessary to meet the patient-specific needs as identified in the comprehensive assessment, including identification of the responsible discipline(s), and the measurable outcomes that the HHA anticipates will occur as a result of implementing and coordinating the plan of care. Upon implementation of the PDGM, we will monitor home health utilization, including the provision of therapy services. Finally, we remind commenters that section 51001(a)(3)(B) of the BBA of 2018 prohibits the use of therapy thresholds as part of the overall case-mix adjustment for CY 2020 and subsequent years. Consequently, we have no regulatory discretion in this matter.