AGENCY:

Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior.

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), determine threatened species status under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (Act), as amended, for the meltwater lednian stonefly (Lednia tumana) and the western glacier stonefly (Zapada glacier), both aquatic species from alpine streams and springs. Meltwater lednian stoneflies are found in Montana and Canada, and western glacier stoneflies are found in Montana and Wyoming. The effect of this regulation will be to add these species to the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. We also finalize a rule under the authority of section 4(d) of the Act that provides measures that are necessary and advisable to provide for the conservation of these species. We have also determined that designation of critical habitat for these species is not prudent.

DATES:

This rule becomes effective December 23, 2019.

ADDRESSES:

This final rule is available at http://www.regulations.gov in Docket No. FWS-R6-ES-2016-0086 and at https://www.fws.gov/mountain-prairie/es/meltwaterLednianStonefly.php and at https://www.fws.gov/mountain-prairie/es/westernGlacierStonefly.php on the internet. Comments and materials we received, as well as supporting documentation we used in preparing this rule, are available for public inspection at http://www.regulations.gov. Comments, materials, and documentation that we considered in this rulemaking will be available by appointment, during normal business hours at: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Montana Ecological Services Office, 585 Shepard Way, Suite 1, Helena, MT 59601; 406-449-5225.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Jodi Bush, Office Supervisor, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Montana Ecological Services Field Office, 585 Shepard Way, Suite 1, Helena, MT 59601, by telephone 406-449-5225. Persons who use a telecommunications device for the deaf may call the Federal Relay Service at 800-877-8339.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Executive Summary

Why we need to publish a rule. Under the Endangered Species Act, a species may warrant protection through listing if it is endangered or threatened throughout all or a significant portion of its range. Listing a species as an endangered or threatened species can only be completed by issuing a rule.

What this document does. This rule will add the meltwater lednian stonefly (Lednia tumana) and western glacier stonefly (Zapada glacier) as threatened species to the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife in title 50 of the Code of Federal Regulations at 50 CFR 17.11(h) with a rule issued under section 4(d) of the Act (hereafter referred to as a “4(d) rule”) at 50 CFR 17.47.

The basis for our action. Under the Endangered Species Act, we can determine that a species is an endangered or threatened species based on any of five factors: (A) The present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range; (B) Overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes; (C) Disease or predation; (D) The inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; or (E) Other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence. We have determined that habitat fragmentation and degradation in the form of declining streamflows and increasing water temperatures resulting from climate change are currently affecting habitat for the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly (Factor A).

Based on empirical evidence, most glaciers supplying cold water to meltwater lednian and western glacier stonefly habitats in Glacier National Park (GNP) are projected to melt by 2030. As a result, habitat with a high probability of occupancy for the meltwater lednian stonefly is modeled to decrease 81 percent by 2030 (Muhlfeld et al. 2011, p. 342). A decrease in distribution of western glacier stonefly has already been documented. Drought is expected to further reduce the amount of habitat occupied by meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly, due to reductions of meltwater from seasonal snowpack and anticipated future reduction of flow from other meltwater sources in the foreseeable future (Factor E). As a result of this anticipated loss of habitat, only a few refugia streams and springs are expected to persist in the long term. Recolonization of intermittent habitats where known occurrences of either species are extirpated is not anticipated, given the poor dispersal abilities of similar stonefly species. Threats to meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly habitat are currently occurring rangewide, are based on empirical evidence of past and current glacial melting, and are expected to continue into the foreseeable future.

Peer review and public comment. We sought comments from seven objective and independent specialists (and received three responses) to ensure that our determination is based on scientifically sound data, assumptions, and analyses. As directed by the Service's Peer Review Policy dated July 1, 1994 (59 FR 34270) and a recent memo updating the peer review policy for listing and recovery actions (August 22, 2016), we invited these peer reviewers to comment on our listing proposal. We also considered all comments and information received during two public comment periods. All comments received during the peer review process and the public comment periods have either been incorporated throughout this rule or addressed in the Summary of Comments and Recommendations section.

Previous Federal Action

Please refer to the proposed listing rule for the meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly (81 FR 68379, October 4, 2016) for a detailed description of previous Federal actions concerning these species prior to October 4, 2016. In that proposed rule, we explained that we received new information on the western glacier stonefly in August 2016, indicating a larger range than previously known. However, due to a settlement agreement deadline, we were unable to fully incorporate and analyze the new information before publishing our October 4, 2016, 12-month finding and proposed listing rule. In March 2017, we received additional information (separate from the information received in August 2016) on the western glacier stonefly, also indicating a larger range than previously known. On October 31, 2017, we reopened the comment period on our proposed listing rule to allow the public to comment on both sets of new information (82 FR 50360). Now that we have had the opportunity to fully consider this new information from August 2016 and March 2017, we have incorporated it into this final rule.

Our October 4, 2016, proposed rule included a determination that critical habitat for the meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly was prudent but not determinable at that time (81 FR 68379). Since that time, the Service finalized regulations related to listing species and designating critical habitat (84 FR 45020, August 27, 2019), which revised the regulations that implement section 4 of the Act and clarify circumstances in which critical habitat may be found not prudent. Regulations at 50 CFR 424.12(a)(1) provide the circumstances when critical habitat may be not prudent, and we have determined that a designation of critical habitat for these species is not prudent, as discussed further below.

Our October 4, 2016, proposed rule also referenced a section of the regulation that provided threatened species with the same protections as endangered species also known as “blanket rules” (50 CFR 17.31). The Service has since published regulations on August 27, 2019 (84 FR 44753), amending 50 CFR 17.31 and 17.71 that state “the blanket rules will no longer be in place, but the Secretary will still be required to make a decision about what regulations to put in place for the species.” While the Service always had the ability to promulgate species-specific 4(d) rules for threatened species, moving forward we will promulgate a species-specific 4(d) rule for each species that we determine meets the definition of a threatened species. As explained below, in the preamble to our 2016 proposed rule, we determined that a rule that included the prohibitions set forth in 50 CFR 17.21 for endangered species would be necessary and advisable for the conservation of the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly. Consequently, we are promulgating a species-specific 4(d) rule that outlines the protections that were described in the 2016 proposed rule; see Provisions of the 4(d) Rule, below.

I. Final Listing Determination

Background

Both the meltwater lednian stonefly (e.g., Baumann 1975, p. 18; Baumann et al. 1977, pp. 7, 34; Newell et al. 2008, p. 181; Stark et al. 2009, entire) and western glacier stonefly (Baumann 1975, p. 30; Stark 1996, entire; Stark et al. 2009, p. 8) are recognized as valid species by the scientific community. Both stonefly species begin life as eggs, hatch into aquatic nymphs, and later mature into winged adults, surviving briefly on land before reproducing and dying. Meltwater habitat for meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly is supplied by glaciers and rock glaciers, as well as by four other sources: (1) Seasonal snow, (2) perennial snow, (3) alpine springs, and (4) ice masses (Giersch et al. 2017, p. 2584). Please refer to the proposed listing rule for the meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly (81 FR 68379, October 4, 2016) for a full discussion of taxonomy, species descriptions, and biology. We have received no new substantive information on those topics since that time.

Distribution and Abundance

Meltwater Lednian Stonefly

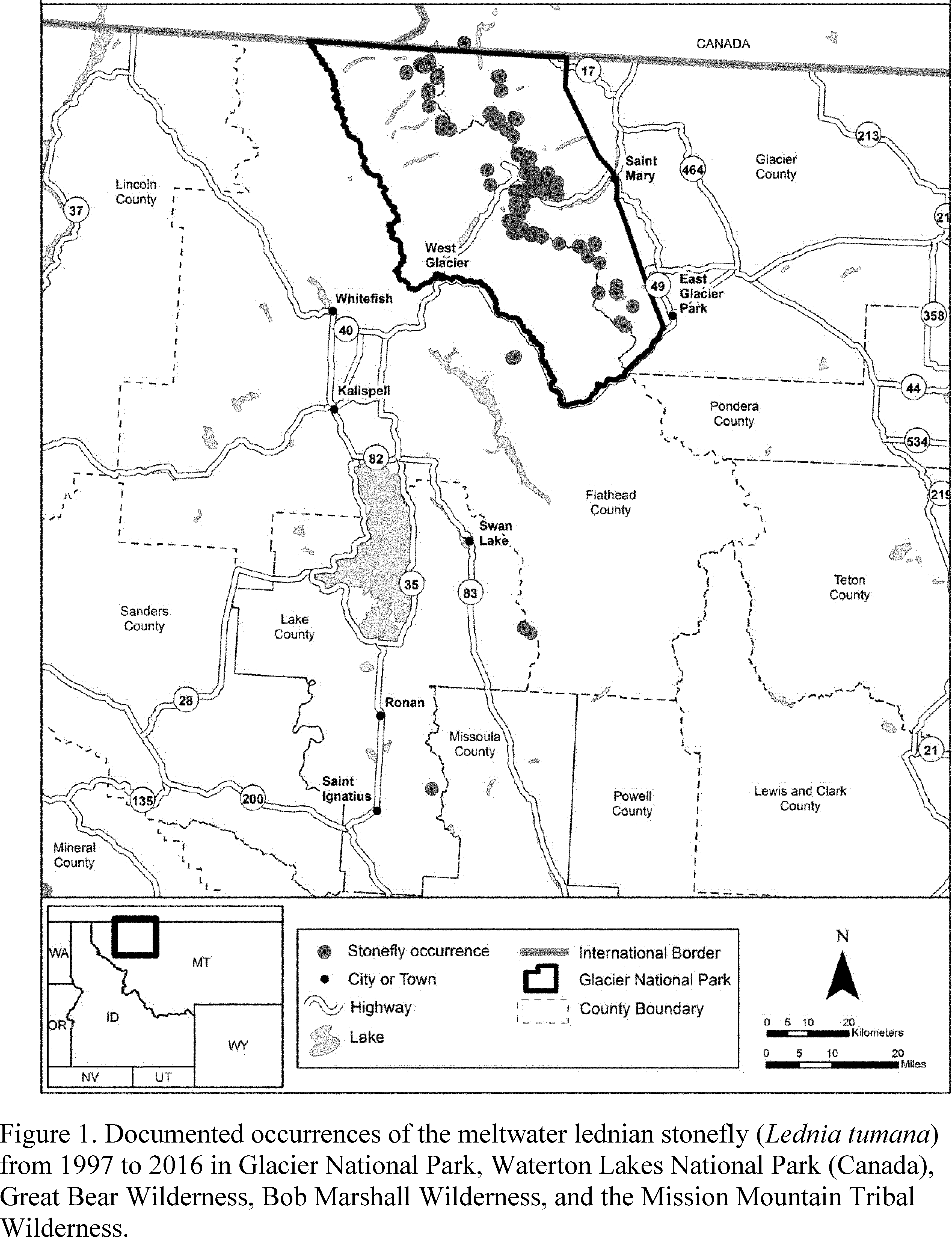

Meltwater lednian stoneflies are known to occur in northwestern Montana and southwest Alberta (Giersch et al. 2017; p. 2582). Specifically, meltwater lednian stoneflies are known to occur in 113 streams: 109 in Glacier National Park (GNP), 2 south of GNP on National Forest land, 1 south of GNP on tribal land (Figure 1; Giersch et al. 2017; p. 2582), and 1 north of GNP in Waterton Lakes National Park in Alberta, Canada (Donald and Anderson 1977, p. 114; Baumann and Kondratieff 2010, p. 315; Giersch 2017, pers. comm.). In the proposed rule (81 FR 68379, October 4, 2016), we indicated meltwater lednian stoneflies were known from historical collections in Waterton Lakes National Park in Canada, but were not known to be extant there. However, recent surveys conducted after the proposed rule was published have also documented the species in the same watershed in Waterton Lakes National Park where they were sampled historically (Giersch 2017, pers. comm.). Meltwater lednian stoneflies occupy relatively short reaches of streams [mean = 592 meters (m) (1,942 feet; ft); standard deviation = 455 m (1,493 ft)] below meltwater sources (for description, see Habitat section below; Giersch et al. 2017; p. 2582). Meltwater lednian stoneflies can attain moderate to high densities [(350-5,800 per square m) (32-537 per square ft)] (e.g., Logan Creek: Baumann and Stewart 1980, p. 658; National Park Service (NPS) 2009, entire; Muhlfeld et al. 2011, p. 342; Giersch 2016, pers. comm.). Given this range of densities and a coarse assessment of available habitat, we estimated the abundance of meltwater lednian stonefly in the millions of individuals; however, no population trend information is available for the meltwater lednian stonefly.

Western Glacier Stonefly

Western glacier stoneflies are known to occur in 16 streams: 6 in GNP, 4 in Grand Teton National Park (GTNP), and 6 in the Absaroka/Beartooth Wilderness on the Custer/Gallatin National Forest (Figure 2; Giersch et al. 2017, p. 2584; Giersch 2017, pers. comm.). The number of streams known to be occupied by western glacier stonefly has increased from the number reported in the proposed rule, due to new information received after the proposed rule was published (Hotaling et al. 2017, entire; Giersch et al. 2017, p. 2584). Similar to the meltwater lednian stonefly, western glacier stoneflies are found on relatively short reaches of streams [mean = 569 m (1,869 ft); standard deviation = 459 m (1,506 ft)] in close proximity to meltwater sources (Giersch et al. 2017). Western glacier stoneflies can attain moderate densities [(400-2,300 per square m) (37-213 per square ft)] in GNP (Giersch 2016, pers. comm.). Lower densities of western glacier stoneflies have been reported in GTNP [(up to 11-56 per square m) (up to 1-5 per square ft)] (Tronstad 2017, pers. comm.). Given this range of densities and a coarse assessment of available habitat, we estimated the abundance of the western glacier stonefly to be in the tens of thousands of individuals, presumably less numerous than the meltwater lednian stonefly.

The recent discovery and subsequent genetic confirmation of western glacier stoneflies in streams in GTNP and the Absaroka/Beartooth Wilderness has increased the known range of the species by about 500 kilometers (km) (~311 miles (mi)) southward (Hotaling et al. 2017, entire; Giersch et al. 2017, p. 2585). However, western glacier stoneflies have decreased in distribution among and within six streams in GNP where the species was known to occur in the 1960s and 1970s (Giersch et al. 2015, p. 58).

The northern distributional limits of the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly are not known. Potential habitat for meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies, which appears to be similar to the habitat both species are currently occupying, exists in the area of Banff and Jasper National Parks, Alberta, Canada. Aquatic invertebrate surveys have been conducted in this area, and no specimens of either species were found, although it is likely that sampling did not occur close enough to glaciers or icefields to detect either meltwater lednian or western glacier stonefly, if indeed they were present (Hirose 2016, pers. comm.). Sampling in this area for both meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies is planned for the future and would help fill in an important data gap with regard to northern distributional limits of both species.

Habitat

Meltwater Lednian Stonefly

The meltwater lednian stonefly is found in high-elevation, alpine streams (Baumann and Stewart 1980, p. 658; Montana Natural Heritage Program 2010a) originating from meltwater sources, including glaciers and small icefields, perennial and seasonal snowpack, alpine springs, and glacial lake outlets (Hauer et al. 2007, p. 107; Giersch et al. 2017, p. 2584). These streams are believed to be fishless, due to their high gradient. Meltwater lednian stoneflies are known from alpine streams where modeled maximum water temperatures do not exceed 10 degrees Celsius (°C) (50 degrees Fahrenheit (°F)) (Giersch et al. 2017, p. 2584), although the species can withstand higher water temperatures (~20 °C; 68 °F) for short periods of time (Treanor et al. 2013, p. 602). In general, the alpine streams inhabited by the meltwater lednian stonefly are presumed to have very low nutrient concentrations (low nitrogen and phosphorus), reflecting the nutrient content of the glacial or snowmelt source (Hauer et al. 2007, pp. 107-108). During the daytime, meltwater lednian stonefly nymphs prefer to occupy the underside of rocks or larger pieces of bark or wood (Baumann and Stewart 1980, p. 658; Giersch et al. 2017, p. 2579).

Western Glacier Stonefly

Western glacier stoneflies are found in high-elevation, alpine streams closely linked to the same meltwater sources as the meltwater lednian stonefly (Giersch et al. 2017; p. 2584). The specific thermal tolerances of the western glacier stonefly are not known. However, all recent collections of the western glacier stonefly in GNP have occurred in habitats with daily maximum water temperatures less than 13.3 °C (55.9 °F) (Giersch et al. 2017, p. 2584). Further, abundance patterns for other species in the Zapada genus in GNP indicate preferences for the coolest environmental temperatures, such as those found at high elevation in proximity to headwater sources (Hauer et al. 2007, p. 110). Daytime microhabitat preferences of the western glacier stonefly appear similar to those for the meltwater lednian stonefly as described above (Giersch et al. 2017, p. 2579).

Summary of Biological Status and Threats

Section 4 of the Act (16 U.S.C. 1533) and its implementing regulations (50 CFR part 424) set forth the procedures for determining whether a species meets the definition of “endangered species” or “threatened species.” The Act defines an “endangered species” as a species that is “in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range,” and a “threatened species” as a species that is “likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range.” The Act requires that we determine whether a species meets the definition of “endangered species” or “threatened species” because of any of the following factors: (A) The present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range; (B) Overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes; (C) Disease or predation; (D) The inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; or (E) Other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence.

Our implementing regulations at 50 CFR 424.11(d) set forth a framework within which we evaluate the foreseeable future on a case-by-case basis. The term foreseeable future extends only so far into the future as the Services can reasonably determine that both the future threats and the species' responses to those threats are likely. The foreseeable future extends only so far as the predictions about the future are reliable. “Reliable” does not mean “certain”; it means sufficient to provide a reasonable degree of confidence in the prediction. Analysis of the foreseeable future uses the best scientific and commercial data available and should consider the timeframes applicable to the relevant threats and to the species' likely responses to those threats in view of its life-history characteristics.

Below is a summary of biological status and threats for listing factors A and E, including new information and citations provided to us during the peer review and public comment period. See the proposed listing rule for information on biological status and threats for listing factors B, C, and D (81 FR 68379, October 4, 2016; pp. 68390-68392). We did not make substantive changes to listing factors B, C, and D between the proposed and final listing rules because we have received no new substantive information relevant to our analysis of those factors. Also, see the proposed listing rule for discussion of synergistic effects and the Factor E discussion in this rule, which addresses comments from a peer reviewer with regard to synergistic effects (81 FR 68379, October 4, 2016, pp. 68392-68393).

For listing factors A and E, we made substantive changes between the proposed and final listing rules. As described further below in Summary of Changes from the Proposed Rule, in the proposed listing rule, we identified populations of meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly based on watershed boundaries. However, multiple peer reviewers observed the need for empirical evidence to support that assessment. Therefore, we have updated our explanation to describe the number of streams occupied by both meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly in our Factors A and E analyses. In addition, we received updated information on the distribution of meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly after the proposed rule was published. Meltwater lednian stonefly are now known from southwest Alberta, Canada (Giersch et al. 2017; p. 2582). In addition, new information documented and genetically confirmed the presence of western glacier stonefly approximately 500 km (311 mi) farther south than previously known (Giersch et al. 2016, p. 28; Hotaling et al. 2017, entire). These southern populations of western glacier stonefly were in the Absaroka-Beartooth wilderness in southern Montana and in Grand Teton National Park in northwestern Wyoming. As a result of this new information, we have now identified a total of 16 streams occupied by western glacier stonefly. Here, we analyze how both species are affected by threats under Factors A and E in all of their currently known locations.

Factor A. The Present or Threatened Destruction, Modification, or Curtailment of Its Habitat or Range

Meltwater lednian stoneflies occupy remote, high-elevation alpine habitats in GNP and several proximate watersheds. Western glacier stoneflies occupy similar habitats in GNP, GTNP, and the Absaroka/Beartooth Wilderness. The remoteness of these habitats largely precludes overlap with human uses and typical land management activities (e.g., forestry, mining, irrigation) that have historically modified habitats of many species. However, these relatively pristine, remote habitats are not expected to be immune to the effects of climate change. Thus, our analysis under Factor A focuses on the expected effects of climate change on meltwater lednian and western glacier stonefly habitats.

Climate Change

See the proposed listing rule for general background information on global climate change (81 FR 68379, October 4, 2016).

Uncertainty in Climate Projections

Any model (representation of something) carries with it some level of uncertainty. Consequently, there is uncertainty in climate projections and related impacts across and within different regions of the world (e.g., Glick et al. 2011, pp. 68-73; Deser et al. 2012, entire; International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2014, pp. 12, 14). This uncertainty can come from multiple sources, including type, amount, and quality of evidence, changing likelihoods of diverse outcomes, ambiguously defined concepts or terminology, or human behavior (IPCC 2014, pp. 37, 56, 58, 128). Methods developed to convey uncertainty in climate projections include quantifying uncertainty (IPCC 2014, p. 2) or analyzing for trends among climate projections (IPCC 2014, pp. 8, 10). Also, uncertainty in climate projections can be reduced by using more regionalized data to produce higher resolution, more accurate climate projections (Glick et al. 2011, pp. 58-61). This uncertainty was considered in this determination. We note that despite the inherent uncertainties associated with climate models/projections, empirical data are used to develop climate models. These models and their associated projections often constitute the best available science, in the absence of other relevant information.

Regional Climate

The western United States appears to be warming faster than the global average. In the Pacific Northwest, regionally averaged temperatures have risen 0.8 °C (1.5 °F) over the last century and as much as 2 °C (4 °F) in some areas and are projected to increase by another 1.5 to 5.5 °C (3 to 10 °F) over the next 100 years (Karl et al. 2009, p. 135). Since 1900, the mean annual air temperature for GNP and the surrounding region has increased 1.3 °C (2.3 °F), which is 1.8 times the global mean increase (U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) 2010, p. 1). Warming also appears to be pronounced in alpine regions globally (e.g., Hall and Fagre 2003, p. 134 and references therein). For the purposes of this final rule, we consider the foreseeable future for anticipated effects of climate change on the alpine environment to be approximately 35 years (~year 2050) based on two factors. First, various global climate models and emissions scenarios provide consistent projections within that timeframe (IPCC 2014, p. 11). Second, the effect of climate change on glaciers in GNP has been modeled within that timeframe (e.g., Hall and Fagre 2003, entire; Brown et al. 2010, entire).

Habitats for both the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly originate from meltwater sources that will be impacted by any projected warming, including glaciers, rock glaciers and small icefields, perennial and seasonal snowpack, alpine springs, and glacial lake outlets (Hauer et al. 2007, p. 107; Giersch et al. 2017, p. 2584). The alteration or loss of these meltwater sources and perennial habitat has direct consequences on both meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly populations. Below, we provide an overview of expected rate of loss of meltwater sources as a result of climate change, followed by the projected effects to stonefly habitat from altered stream flows and water temperatures.

Glacier Loss

Glacier loss in GNP is directly influenced by climate change (e.g., Hall and Fagre 2003, entire; Fagre 2005, entire). When established in 1910, GNP contained approximately 150 glaciers larger than 0.1 square kilometer (25 acres) in size, but presently only 25 glaciers larger than this size remain (Fagre 2005, pp. 1-3; USGS 2005, 2010). Hall and Fagre (2003, entire) modeled the effects of climate change on glacier persistence in GNP's Blackfoot-Jackson basin using two climate scenarios based on empirical air temperature and glacier melt rate data: (1) Doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide by 2030 (CO2) and (2) linear temperature-extrapolation. Under the CO2 scenario, regional air temperatures were projected to increase 3.3 °C by 2100, and glaciers were projected to completely melt in GNP by 2030, with projected increases in winter precipitation not expected to buffer glacial shrinking (Hall and Fagre 2003, pp. 137-138). Under the linear temperature-extrapolation scenario, regional air temperatures were projected to increase 0.45 °C by 2100, and glaciers were projected to completely melt in GNP by 2277 (Hall and Fagre 2003, pp. 137-138).

We determined that the CO2 scenario was likely to better represent future air temperature conditions and glacier persistence in GNP for multiple reasons. First, the projected future air temperature increase of 0.45 °C (by 2100) under the linear temperature-extrapolation scenario is now projected to occur by 2035 (IPCC 2014, p. 10)—65 years sooner than projected under the linear temperature-extrapolation. This new projection is based on 11 additional years of climate data that were not available in 2003. Thus, the linear temperature-extrapolation model is overly conservative. Second, while both future air temperature projections (i.e., 3.3 °C and 0.45 °C) from Hall and Fagre 2003 are bracketed by newer projections of air temperature rise from varying climate scenarios in IPCC 2014 (p. 10), the mean annual air temperature for GNP and the surrounding region is increasing at 1.8 times the global rate (USGS 2010, p. 1). This means that the CO2 scenario with its higher future air temperature projection (i.e., 3.3 °C) is more likely to represent the likely air temperature change in the GNP area. Indeed, the range of projected future air temperatures in three of the four global climate scenarios used in IPCC 2014 (i.e., Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) 4.5, 6.0, and 8.5; IPCC 2014, p. 8) include 3.3 °C, after taking into account the regional increase of projected air temperatures of 1.8 times the global rate.

Conversely, even the most conservative (i.e., lowest emissions) global climate scenario used in IPCC 2014 (RCP 2.6) does not encompass the air temperature projection (0.45 °C) from the linear temperature-extrapolation model, after taking into account the regional increase of projected air temperatures of 1.8 times the global rate. Third, recent observations of glacier melting rates indicate faster melt than projected by the CO2 scenario (Muhlfeld et al. 2011, p. 339). Intuitively, this indicates the CO2 scenario would be expected to better represent future air temperatures and glacier persistence, relative to the more conservative linear temperature-extrapolation model. For these reasons, we expect the CO2 scenario to better represent future air temperature increase and glacier persistence in GNP than the linear temperature-extrapolation scenario.

A more recent analysis of Sperry Glacier in GNP estimates this particular glacier (1 of 25 glaciers remaining from the historical 150 glaciers larger than 25 acres) may persist through 2080, in part due to annual avalanche inputs from an adjacent cirque wall (Brown et al. 2010, p. 5). We are not aware of any other published studies using more recent climate scenarios that speak directly to anticipated conditions of the remaining glaciers in GNP. Thus, we largely rely on Hall and Fagre's (2003) projections under the CO2 scenario in our analysis, supplemented with more recent glacier-specific studies where appropriate (e.g., Brown et al. 2010, entire).

The longevity of glaciers and snowfields in GTNP and the Absaroka/Beartooth Wilderness is unknown. While most of these glaciers occur at higher elevations than those in GNP, multiple factors other than elevation influence glacial retreat rates, including size, latitude, and aspect (Janke 2007, p. 80). Middle Teton glacier in GTNP is projected to persist through the year 2100 (Tootle et al. 2010, p. 29); however, this projection is based on the assumption that future glacial retreat rates will be the same as those observed during the period of study (i.e., 1967-2006; Tootle et al. 2010, p. 29). This scenario appears unlikely because glacier size is an important variable in glacier retreat rates (Janke 2007, p. 80), whereby the rate of glacial melting increases as glaciers shrink. Thus, the longevity of glaciers and snowfields in GTNP and the Absaroka/Beartooth Wilderness is unclear at this time.

Petersen Glacier in GTNP is a rock glacier that provides meltwater to one stream occupied by the western glacier stonefly. A rock glacier is a glacier that is covered by rocks and other debris. The size of Petersen Glacier is unknown because it is mostly covered in rocks. However, rock glaciers melt more slowly than alpine glaciers because of the insulating properties of the debris covering the main glacial ice mass (Janke 2007, p. 80; Pelto 2000, pp. 39-40; Brenning 2005, p. 237). Thus, cold-water habitats originating from rock glaciers may be present longer into the future than from other meltwater sources.

Loss of Other Meltwater Sources

Meltwater in meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly habitat is supplied by glaciers and rock glaciers, as well as by four other sources: (1) Seasonal snow, (2) perennial snow, (3) alpine springs, and (4) ice masses (Giersch et al. 2017, p. 2584). Seasonal snow is that which accumulates and melts seasonally, with the amount varying year to year depending on annual weather events. Perennial snow is some portion of a snowfield that does not generally melt on an annual basis, the volume of which can change over time. Alpine springs originate from some combination of meltwater from snow, ice masses or glaciers, and groundwater. Ice masses are smaller than glaciers and do not actively move as glaciers do.

The sources of meltwater that supply meltwater lednian and western glacier stonefly habitat are expected to be affected by the changing climate at different time intervals. In general, we expect all meltwater sources to decline under a changing climate, given the relationship between climate and glacial melting (Hall and Fagre 2003, entire; Fagre 2005, entire) and recent climate observations and modeling (IPCC 2014, entire). It is likely that seasonal snowpack levels will be most immediately affected by climate change, as the frequency of more extreme weather events increases (IPCC 2014, p. 8). These extremes may result in increased seasonal snowpack in some years and reduced snowpack in others.

We expect that effects to meltwater lednian stonefly habitats south of GNP may occur sooner in time than those discussed for GNP. The timing of snowfield and ice mass disappearance is expected to be before the majority of glacial melting (i.e., 2030), because perennial snowpack and ice masses are less dense than glaciers and typically have smaller volumes of snow and ice. However, alpine springs, at least those supplemented with groundwater, may continue to be present after complete glacial melting. Our analysis primarily focuses on effects to the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly and their habitat within GNP because more data are available for those areas.

Streamflows

Meltwater streams—Declines in meltwater sources are expected to affect flows in meltwater streams in GNP. Glaciers and other meltwater sources act as water banks, whose continual melt maintains streamflows during late summer or drought periods (Hauer et al. 2007, p. 107). Following glacier loss, declines in streamflow and periodic dewatering events are expected to occur in meltwater streams in the northern Rocky Mountains (Hauer et al. 1997, p. 909; Leppi et al. 2012, p. 1105; Clark et al. 2015, p. 14). In similarly glaciated regions, intermittent stream flows have been documented following glacial recession and loss (Robinson et al. 2015, p. 8). By 2030, the modeled distribution of habitat with the highest likelihood of supporting meltwater lednian stoneflies is projected to decline by 81 percent in GNP, compared to the present amount of habitat (Muhlfeld et al. 2011, p. 342). Desiccation (drying) of these habitats, even periodically, could eliminate entire populations of the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly because the aquatic nymphs need perennial flowing water to breathe and to mature before reproducing (Stewart and Harper 1996, p. 217). Given that both stonefly species are believed to be poor dispersers (similar to other Plecopterans; Baumann and Gaufin 1971, p. 277), recolonization of previously occupied habitats is not expected following dewatering and extirpation events. Lack of recolonization by either stonefly species is expected to lead to further isolation between extant occupied streams.

Currently, 107 streams (of 113) occupied by meltwater lednian stonefly and 12 streams (of 16) occupied by western glacier stonefly are supplied by seasonal snowpack, perennial snowpack, ice masses, and some glaciers (Giersch et al. 2017, p. 2584; Giersch 2017, pers. comm.). Meltwater from these sources is expected to become inconsistent by 2030 (Hall and Fagre 2003, p. 137). Although the rate at which flows will be reduced or at which dewatering events will occur in these habitats is unclear, we expect, at a minimum, to see decreases in abundance and distribution of both species as a result. By 2030, we also anticipate the remaining occupied habitats to be further isolated relative to current conditions.

Alpine springs—Declines in meltwater sources are also expected to affect flows in alpine springs, although likely on a longer time scale than for meltwater streams. Flow from alpine springs in the northern Rocky Mountains originates from glacial or snow meltwater in part, sometimes supplemented with groundwater (Hauer et al. 2007, p. 107). For this reason, some alpine springs are expected to be more climate-resilient and persist longer than meltwater streams and may serve as refugia areas for meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies, at least in the near term (Ward 1994, p. 283). However, small aquifers feeding alpine springs are ultimately replenished by glacial and other meltwater sources in alpine environments (Hauer et al. 1997, p. 908).

Once glaciers in GNP melt, small aquifer volumes and the groundwater influence they provide to alpine springs are expected to decline. Thus by 2030, even flows from alpine springs supplemented with groundwater are expected to decline (Hauer et al. 1997, p. 910; Clark et al. 2015, p. 14). This expected pattern of decline is consistent with observed patterns of low flow from alpine springs in the Rocky Mountains region and other glaciated regions during years with little snowpack (Hauer et al. 1997, p. 910; Robinson et al. 2015, p. 9). Further, following complete melting of glaciers, drying of alpine springs in GNP might be expected if annual precipitation fails to recharge groundwater supplies. Changes in future precipitation levels due to climate change in the GNP region are projected to range from relatively unchanged to a small (~10 percent) annual increase (IPCC 2014, pp. 20-21).

Only 6 streams (out of 113) occupied by meltwater lednian stonefly and 4 streams (out of 16) occupied by western glacier stonefly originate from alpine springs. Thus, despite the potential for some alpine springs to provide refugia for both stonefly species after glaciers melt, only a few populations may benefit from these potential refugia.

Glacial lake outlets—Similar to alpine springs, flow from glacial lake outlets is expected to diminish gradually following the projected melting of most glaciers around 2030. Glacial lakes are expected to receive annual inflow from melting snow from the preceding winter, although the amount by which it may be reduced after complete glacial melting is unknown. Reductions in flow from glacial lakes are expected to, at a minimum, decrease the amount of available habitat for both meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies.

One occurrence each of the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly occupy a glacial lake outlet (Upper Grinnell Lake; Giersch et al. 2015, p. 58; Giersch et al. 2017, p. 2588). Thus, despite the fact that this habitat type may continue to provide refugia for both stonefly species even after the complete loss of glaciers, a small percentage of each species may benefit from these potential refugia. As such, we conclude that habitat degradation in the form of reduced streamflows due to the effects of climate change will impact 95 percent of streams occupied by meltwater lednian stonefly and 75 percent of streams occupied by western glacier stonefly populations within the foreseeable future.

Water Temperature

Meltwater streams—Glaciers act as water banks, whose continual melting maintains suitable water temperatures for meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly during late summer or drought periods (Hauer et al. 2007, p. 107; USGS 2010). As glaciers melt and contribute less volume of meltwater to streams, water temperatures are expected to rise (Hauer et al. 1997, p. 909; Clark et al. 2015, p. 14). Aquatic invertebrates have specific temperature needs that influence their distribution (Fagre et al. 1997, p. 763; Lowe and Hauer 1999, pp. 1637, 1640, 1642; Hauer et al. 2007, p. 110); complete glacial melting may result in an increase in water temperatures above the physiological limits for survival or optimal growth for the meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies.

As a result of melting glaciers and a lower volume of meltwater input into streams, we expect upward elevational shifts of meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly, as they track their optimal thermal preferences. However, both meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly already occupy the most upstream portions of these habitats and can move upstream only to the extent of the receding glacier/snowfield. Once the glaciers and snowfields completely melt, meltwater lednian stoneflies and western glacier stoneflies will have no physical habitat left to which to migrate upstream. The likely result of this scenario would be the extirpation of stoneflies from these habitats. Other indirect effects of warming water temperatures on both stonefly species could include encroaching aquatic invertebrate species that may be superior competitors, or changed thermal conditions that may favor the encroaching species in competitive interactions between the species (condition-specific competition).

The majority of streams occupied by meltwater lednian stonefly and one stream occupied by western glacier stonefly are habitats that may warm significantly by 2030, due to the projected complete melting of glaciers and snow and ice fields. Increasing water temperatures may be related to recent distributional declines of western glacier stoneflies within GNP (Giersch et al. 2015, p. 61).

Alpine springs— Although meltwater contributions to alpine springs are expected to decline as glaciers and perennial snow melt, water temperature at the springhead may remain relatively consistent due to the influence of groundwater, at least in the short term. The springhead itself may provide refugia for both meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies, although stream reaches below the actual springhead are expected to exhibit similar increases in water temperature in response to loss of glacial meltwater as those described for meltwater streams. However, as described above, some alpine springs may eventually dry up after glacier and snowpack loss, if annual precipitation fails to recharge groundwater supplies (Hauer et al. 1997, p. 910; Robinson et al. 2015, p. 9).

Only six streams occupied by the meltwater lednian stonefly (5 percent of total known occupied streams) and four streams occupied by the western glacier stonefly (25 percent of total known occupied streams) originate from alpine springs. Thus, despite the fact that alpine springs may be more thermally stable than meltwater streams and provide thermal refugia to both the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly, a small percentage of each species may benefit from these potential refugia.

Glacial lake outlets— Similar to alpine springs, glacial lake outlets are more thermally stable habitats than meltwater streams. This situation is likely due to the buffering effect of large volumes of glacial lake water supplying these habitats. It is anticipated that the buffering effects of glacial lakes will continue to limit increases in water temperature to outlet stream habitats, even after the loss of glaciers. However, water temperatures are still expected to increase over time following complete glacial loss in GNP. It is unknown whether water temperature increases in glacial lake outlets will exceed presumed temperature thresholds for meltwater lednian and western glacier stonefly in the future. However, given the low water temperatures recorded in habitats where both species have been collected, even small increases in water temperature of glacial lake outlets may be biologically significant and detrimental to the persistence of both species for the reasons described previously.

One stream occupied by meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly is a glacial lake outlet (Upper Grinnell Lake; Giersch et al. 2015, p. 58; Giersch et al. 2017). Thus, despite the fact that glacial lake outlets may be more thermally stable than meltwater streams and provide thermal refugia to both the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly, a small percentage of each species may benefit from these potential refugia. Consequently, we conclude that changes in water temperature from climate change are a threat to most populations of both stonefly species now and into the future.

Maintenance and Improvement of National Park Infrastructure

Glacier National Park and Grand Teton National Park are managed to protect natural and cultural resources, and the landscapes within these parks are relatively pristine. However, both National Parks include a number of human-built facilities and structures that support visitor services, recreation, and access, such as the Going-to-the-Sun Road (which bisects GNP) and numerous visitor centers, trailheads, overlooks, and lodges (e.g., NPS 2003a, pp. S3, 11). Maintenance and improvement of these facilities and structures could conceivably lead to disturbance of the natural environment.

In the proposed listing rule, we mentioned we were aware of one water diversion on Logan Creek in GNP that was scheduled to be retrofitted by the NPS. Logan Creek is occupied by meltwater lednian stoneflies. Since publication of the proposed listing rule, the water diversion retrofit project has been redesigned to avoid any dewatering or instream work in the proposed section of Logan Creek (Aceituno 2017, pers. comm.). Thus, this project is no longer expected to impact meltwater lednian stoneflies, and we no longer incorporate this project into our analysis.

We do not have any information indicating that maintenance and improvement of other GNP or GTNP facilities and structures is affecting either meltwater lednian or western glacier stoneflies or their habitat. While roads and trails provide avenues for recreationists (primarily hikers) to access backcountry areas, most habitats for both the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly are located in steep, rocky areas that are not easily accessible, even from backcountry trails. Most documented occurrences of both species are in remote locations upstream from human-built structures, thereby precluding any impacts to stonefly habitat from maintenance or improvement of these structures. Given the above information, we conclude that maintenance and improvement of National Park facilities and structures, and the resulting improved access into the backcountry for recreationists, are unlikely to affect meltwater lednian or western glacier stonefly or their habitat.

National Park Visitor Impacts

In 2015, GNP hosted 2.3 million visitors (NPS 2015, entire) and, in 2016, GTNP hosted 4.8 million visitors (NPS 2016, entire). A few of the recent collection sites for the meltwater lednian stonefly (e.g., Logan and Reynolds Creeks in GNP) are more accessible to the public or adjacent to popular hiking trails in GNP and GTNP. Theoretically, human activity (wading) in streams by anglers or hikers could disturb meltwater lednian stonefly habitat. However, we consider it unlikely that many National Park visitors would actually wade in stream habitats where the species has been collected, because the sites are in small, high-elevation streams situated in rugged terrain, and most would not be suitable for angling due to the absence of fish. In addition, the sites in GNP are typically snow covered into late July or August (Giersch 2010a, pers. comm.), making them accessible for only a few months annually. We also note that the most accessible collection sites in Logan Creek near the Logan Pass Visitor Center and the Going-to-the-Sun Road in GNP are currently closed to public use and entry to protect resident vegetation (NPS 2010, pp. J5, J24). Collection sites of western glacier stoneflies in GTNP are also relatively inaccessible to most visitors. We conclude that impacts to the meltwater lednian and western glacier stonefly and their habitat from National Park visitors are not likely to occur.

Wilderness Area Visitor Impacts

Three streams occupied by meltwater lednian stonefly are located in wilderness areas adjacent to GNP, and six streams occupied by the western glacier stonefly are located in the Absaroka/Beartooth Wilderness. Visitor activities in wilderness areas are similar to those described for National Parks, namely hiking and angling. No recreational hiking trails are present near the two streams occupied by meltwater lednian stonefly in the Bob Marshall Wilderness and Great Bear Wilderness (USFS 2015, p. 1) or near the stream occurring in the Mission Mountain Tribal Wilderness. There are several hiking trails near streams occupied by the western glacier stonefly in the Absaroka/Beartooth Wilderness. Similar to the National Parks, stream reaches that harbor the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly in these wilderness areas are likely fishless due to the high gradient, so wade anglers are not expected to disturb stonefly habitat. Given the remote nature of and limited access to meltwater stonefly and western glacier stonefly habitat in wilderness areas, we do not anticipate any current or future threats to meltwater lednian stoneflies or western glacier stoneflies or their respective habitats from visitor use.

Summary of Factor A

In summary, we expect climate change impacts to fragment or degrade all habitat types that are currently occupied by meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies, albeit at different rates. Flows in meltwater streams are expected to be affected first, by becoming periodically intermittent and warmer. Drying of meltwater streams and water temperature increases, even periodically, are expected to reduce available habitat in GNP for the meltwater lednian stonefly by 81 percent by 2030. After 2030, flow reductions and water temperature increases due to continued warming are expected to further reduce or degrade remaining refugia habitat (alpine springs and glacial lake outlets) for both meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies. In GTNP and the Absaroka/Beartooth Wilderness, we expect a similar pattern of meltwater stream warming and potential drying. Projected habitat changes are based on observed patterns of flow and water temperature in similar watersheds elsewhere where glaciers have already melted.

We have observed a declining trend in western glacier stonefly distribution over the last 50 years, as air temperatures have warmed in GNP. The addition of newly reported populations of western glacier stonefly provides increased redundancy for the species across its range, bringing the total number of known occupied streams to 13 (up from 4 occupied streams at the time of publishing of the proposed rule). However, the resiliency of all known populations remains low because western glacier stonefly inhabit the most upstream reaches of their meltwater habitats and cannot disperse further upstream if water temperatures warm beyond their thermal tolerances. We expect the meltwater lednian stonefly to follow a similar trajectory, given the similarities between the two stonefly species and their meltwater habitats. Consequently, we conclude that habitat fragmentation and degradation resulting from climate change are significantly affecting both the meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies now and into the future. Given the minimal overlap between stonefly habitat and most existing infrastructure or backcountry activities (e.g., hiking), we conclude any impacts from these activities on either the meltwater lednian stonefly or the western glacier stonefly are low.

Factor B. Overutilization for Commercial, Recreational, Scientific, or Educational Purposes

We are not aware of any threats involving the overutilization or collection of the meltwater lednian or western glacier stonefly for any commercial, recreational, or educational purposes at this time. We are aware that specimens of both species are occasionally collected for scientific purposes to determine their distribution and abundance (e.g., Baumann and Stewart 1980, pp. 655, 658; NPS 2009; Muhlfeld et al. 2011, entire; Giersch et al. 2015, entire). However, both species are comparatively abundant in remaining habitats (e.g., NPS 2009; Giersch 2016, pers. comm.), and we have no information to suggest that past, current, or any collections in the near future will result in population-level effects to either species. Consequently, we do not consider overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes to be a threat to the meltwater lednian or western glacier stonefly now or in the near future.

Factor C. Disease or Predation

We are not aware of any diseases that affect the meltwater lednian or western glacier stonefly. Therefore, we do not consider disease to be a threat to these species now or in the near future.

We presume that nymph and adult meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies may occasionally be subject to predation by bird species such as American dipper (Cinclus mexicanus) or predatory aquatic insects. Fish and amphibians are not potential predators because these species do not occur in the stream reaches containing the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly. The American dipper prefers to feed on aquatic invertebrates in fast-moving, clear alpine streams, and the species is native to GNP. As such, predation by American dipper on these species would represent a natural ecological interaction in the GNP (see Synergistic Effects section below for analysis on potential predation/habitat fragmentation synergy). Similarly, predation by other aquatic insects would represent a natural ecological interaction between the species. We have no evidence that the extent of such predation, if it occurs, represents any population-level threat to either meltwater lednian or western glacier stonefly, especially given that densities of individuals within many of these populations are high. Therefore, we do not consider predation to be a threat to these species now or in the near future. In summary, the best available scientific and commercial information does not indicate that the meltwater lednian or western glacier stonefly is affected by any diseases, or that natural predation occurs at levels likely to negatively affect either species at the population level. Therefore, we do not find disease or predation to be threats to the meltwater lednian or western glacier stonefly now or in the near future.

Factor D. The Inadequacy of Existing Regulatory Mechanisms

Section 4(b)(1)(A) of the Endangered Species Act requires the Service to take into account “those efforts, if any, being made by any State or foreign nation, or any political subdivision of a State or foreign nation, to protect such species. . . .” We consider relevant Federal, State, and Tribal laws and regulations when evaluating the status of the species. A thorough analysis of existing regulatory mechanisms was carried out and described in the proposed listing rule (81 FR 68379, October 4, 2016). No local, State, or Federal laws specifically protect the meltwater lednian or western glacier stonefly.

Factor E. Other Natural or Manmade Factors Affecting Its Continued Existence

Small Population Size/Genetic Diversity

Small population size can increase risk of extinction, if genetic diversity is not maintained (Fausch et al. 2006, p. 23; Allendorf et al. 1997, entire). Genetic diversity in the meltwater lednian stonefly is declining and lower than that of two other stonefly species (Jordan et al. 2017, p. 9). Genetic diversity of western glacier stonefly is lower than other species in the Zapada genus sampled in GNP (Giersch et al. 2015, p. 63). It is presumed that low genetic diversity in meltwater lednian stoneflies and western glacier stoneflies is linked to small effective population sizes and population isolation (Jordan et al. 2017, p. 9; Giersch et al. 2015, p. 63). Population isolation can limit or preclude genetic exchange between populations (Hotaling et al. 2017, p. 9; Fausch et al. 2006, p. 8). However, it is unclear how far into the future population-level effects from loss of genetic diversity may appear in the meltwater lednian and western glacier stonefly. Loss of genetic diversity is typically not an immediate threat even in isolated populations with small effective population sizes (Palstra and Ruzzante 2008, p. 3441), but rather is a symptom of deterministic processes acting on the population (Jamieson and Allendorf 2012, p. 580). In other words, loss of genetic diversity due to small effective population size typically does not drive species to extinction (Jamieson and Allendorf 2012, entire); other processes, such as habitat degradation, have a more immediate and greater impact on species persistence (Jamieson and Allendorf 2012). We acknowledge that loss of genetic diversity can occur in small populations; however, in this case, it appears that projected effects to habitat are the primary threat to both stonefly species, not a loss of genetic diversity that may take many years to manifest.

Restricted Range and Stochastic (Random) Events

Narrow endemic species can be at risk of extirpation from random events such as fire, flooding, or drought. Random events occurring within the narrow range of endemic species have the potential to disproportionately affect large numbers of individuals or populations, relative to a more widely distributed species. A restricted range and stochastic events may have greater impacts on western glacier stonefly, compared to meltwater lednian stonefly, because of considerably fewer populations. However, meltwater lednian stonefly is a narrow endemic as well and may be at higher risk of random events when compared to a more widely distributed species. The risk to meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies from fire appears low, given that most alpine environments within the species' habitats have few trees and little vegetation to burn. The risk to both species from flooding also appears low, given the relatively small watershed areas available to capture and channel precipitation upslope of most stonefly occurrences.

The risk to the meltwater lednian stonefly from drought appears moderate in the near term because 59 of 113 occupied streams are supplied by seasonal or perennial snowmelt, which would be expected to decline first during drought. For the western glacier stonefly, the threat of drought is also moderate because 6 of 16 occupied streams are likely to be affected by variations in seasonal precipitation and snowpack. The risk of drought in the longer term (after 2030 and when complete loss of glaciers is projected) appears high for both stonefly species. Once glaciers melt, drought or extended drought could result in dewatering events in some habitats. Dewatering events would likely extirpate entire populations almost instantaneously. Natural recolonization of habitats affected by drought is unlikely, given the presumed poor dispersal abilities of both stonefly species and general isolation of populations relative to one another (Hauer et al. 2007, pp. 108-110). Thus, we conclude that drought (a stochastic event) will be a threat to both the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly in the future.

Summary of Factor E

The effect of small population size and loss of genetic diversity does not appear to be having immediate impacts on the meltwater lednian stonefly or the western glacier stonefly, given the high densities of individuals within many streams and that potential effects from loss of genetic diversity would likely occur beyond the timeframe in which habitat-related threats are expected to occur. However, the restricted range of the meltwater lednian and western glacier stonefly make both species vulnerable to the stochastic threat of drought, which is expected to negatively affect both species within the future.

Summary of Changes From the Proposed Rule

Based on information received during the peer review process and public comment periods, we made the following substantive changes (listed below) to the Background portion of the preamble to this final listing rule. In addition, we have added species-specific provisions to 50 CFR 17.47 as a result of new rulemaking actions that pertain to the listing of threatened species; these rulemaking actions and the subsequent additions to this rule are described in section II of the preamble (see below), and the regulatory provisions are set forth at the end of this document in the rule language. The prohibitions provided under this 4(d) rule do not differ from those proposed for the species; however, the manner in which they are implemented (via a species-specific rule rather than referring to the “blanket” rule at 50 CFR 17.31) has changed.

1. We incorporated new distribution information for the meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly. This information became available to us after the proposed listing rule was published and included a small range expansion for the meltwater lednian stonefly (southwestern Alberta, Canada) and large range expansion for western glacier stonefly of about 500 km (311 mi) south from their previously known range, to now include multiple streams in GTNP in Wyoming and the Absaroka/Beartooth Wilderness in Montana. This new information updated the number of known streams occupied by western glacier stonefly from 4 to 16. This information was incorporated into the analyses under Factors A and E.

2. We incorporated genetics information from a new study by Hotaling et al. 2017. This new study confirmed through genetic analysis that the western glacier stonefly was present in multiple streams in GTNP in Wyoming and the Absaroka/Beartooth Wilderness in Montana. This information represents the most current assessment of genetic information for western glacier and meltwater lednian stonefly and was not available when the proposed listing rule was published. This new information was incorporated into the analyses under Factors A and E.

3. We incorporated information on how rock glaciers might respond to climate change under Factor A. Rock glaciers are debris-covered glaciers that are expected to melt more slowly than normal glaciers.

4. We incorporated information on site-specific differences in geology, glacial persistence, and stonefly density between GNP and GTNP. This information clarified differences in habitat and stonefly density across the range of the western glacier stonefly and was incorporated into our analysis under Factor A.

5. We updated literature citations throughout Factors A and E. We updated several pieces of literature that were originally cited as unpublished reports, but were subsequently published in scientific journals after the proposed listing rule published in the Federal Register. We incorporated one study on meltwater lednian stonefly genetics that was not cited in the proposed rule (Jordan et al. 2017) in Factor E. We also incorporated two additional studies (Clark et al. 2015; Leppi et al. 2012) on the projected effects of climate change on stream runoff in Factor A.

6. We clarified minor inaccuracies related to stonefly distribution and dispersal capability. This included clarifying areas of uncertainty.

7. We incorporated potential effects of population isolation into our analysis of Factor E. We added a paragraph discussing the potential effects of population isolation and reduced genetic diversity on stonefly viability.

8. We changed the terminology used to describe the distribution of the two species. We used the term “populations” in the proposed listing rule to reference groups of stoneflies in certain areas that we believed likely constituted an interbreeding population. However, there is no empirical evidence to support the use of the term “population,” so we now refer instead to the number of distinct streams that are occupied by both stonefly species when discussing their distribution and current and future status. The terminology change was incorporated into our analyses under Factors A and E.

9. We reevaluated whether critical habitat for both stonefly species is prudent. Our October 4, 2016, proposed rule included a determination that critical habitat for the meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly was prudent but not determinable at that time (81 FR 68379). Since that time, the Service finalized regulations related to listing species and designating critical habitat (84 FR 45020, August 27, 2019), which revised the regulations that implement section 4 of the Act and clarify circumstances in which critical habitat may be found not prudent. Regulations at 50 CFR 424.12(a)(1) provide the circumstances when critical habitat may be not prudent, and we have determined that a designation of critical habitat for these species is not prudent, as discussed further below.

Summary of Comments and Recommendations

In the proposed rule published on October 4, 2016 (81 FR 68379), we requested that all interested parties submit written comments on the proposal by December 5, 2016. We also contacted appropriate Federal and State agencies, scientific experts and organizations, and other interested parties and invited them to comment on the proposal. Newspaper notices inviting general public comment were published in the Kalispell InterLake, Great Falls Tribune, Bozeman Chronicle, Billings Gazette, and Jackson Hole News and Guide. On October 31, 2017, we reopened the comment period on our proposed listing rule to allow the public to comment on new information regarding the known distribution of western glacier stonefly (82 FR 50360). We did not receive any requests for a public hearing. All substantive information provided during both comment periods has either been incorporated directly into this final determination or addressed below.

Peer Reviewer Comments

In accordance with our peer review policy published on July 1, 1994 (59 FR 34270), we solicited expert opinion from seven knowledgeable individuals with scientific expertise that included familiarity with stoneflies and their habitat, biological needs, and threats. We received responses from three of the peer reviewers.

We reviewed all comments received from the peer reviewers for substantive issues and new information regarding the listing of meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly. The peer reviewers generally concurred with our methods and conclusions and provided additional information, clarifications, and suggestions to improve the final rule. Peer reviewer comments are addressed in the following summary and incorporated into this final rule as appropriate.

(1) Comment: Several peer reviewers noted that new genetics information (i.e., Hotaling et al. 2017) for meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies was now available that was not available when the proposed listing rule was published.

Our Response: We are aware of the genetic analysis by Hotaling et al., and we have fully incorporated their findings and conclusions into this final listing rule in the Factors A and E analyses.

(2) Comment: One peer reviewer noted that at least one stream occupied by western glacier stonefly originates from a rock glacier. Since rock glaciers are covered by debris, their rate of melting may differ from those glaciers not covered by debris. The reviewer suggested we add a brief description of this potential phenomenon.

Our Response: We added a paragraph to this final listing rule discussing this phenomenon and its implications for western glacier stonefly habitat in our Factor A analyses.

(3) Comment: One peer reviewer noted that the Service did not consider differences in geology, glacial persistence, and stonefly density between GNP and GTNP in the proposed rule.

Our Response: We made several clarifications and added information on the suggested topics in this final listing rule in our Factor A analyses.

(4) Comment: Several peer reviewers noted that newer literature citations were available to support statements made in the proposed listing rule with regard to stonefly genetics and population isolation.

Our Response: We incorporated the newer literature citations (i.e., Giersch 2017, pers. comm.; Giersch et al. 2015; Giersch et al. 2017; Jordan et al. 2017; Hotaling et al. 2017) and updated all stonefly occurrence data with the most current information from Giersch et al. 2017 in Background and our Factors A and E analyses.

(5) Comment: Several peer reviewers noted inaccuracies in the proposed listing rule in regard to how the Service described stonefly distribution and dispersal capability.

Our Response: We clarified areas of uncertainty with respect to stonefly distribution and dispersal capability. The Service also added several clarifying statements on stonefly distribution to highlight areas of uncertainty in Background and our Factors A and E analyses.

(6) Comment: One peer reviewer noted that the Service did not fully account for the potential effects of population isolation in our threats analysis.

Our Response: We added a paragraph on the potential effects of population isolation, including recent genetics information from Jordan et al. 2017, in our Factor E analyses.

(7) Comment: Several peer reviewers noted that we used the term “population” in the proposed listing rule, but that it was never defined or there was no explanation of how the number of occupied streams translated to the number of stonefly populations.

Our Response: We deleted any reference to a specific number of stonefly populations in the final listing rule. Instead, we report the number of streams known to be occupied by meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies. This approach is consistent with the terminology and methodology used in Giersch et al. 2017, which is the best available science on the status and distribution of both stonefly species. These changes were made in Background and in our Factors A and E analyses.

Comments From States

(8) Comment: A comment from one State expressed concern that the genetic information on western glacier stonefly relied upon in the proposed listing rule was incomplete. The State provided evidence that a more robust genetic analysis was under way, the results (contained in Hotaling et al. 2017) of which would aid in highlighting the distinctness or relatedness among western glacier stoneflies across their known range.

Our Response: We were aware of the ongoing genetic analysis by Hotaling et al., and now that the results are available, we have fully incorporated their findings/conclusions into the final listing rule in our Factors A and E analyses.

(9) Comment: One State provided the results of a recent genetics study (Hotaling et al. 2017) that confirmed western glacier stonefly presence in GTNP and the Absaroka/Beartooth Wilderness. The State did not support listing the western glacier stonefly. Based on the results of the provided information that the species was more widespread than previously believed, the State suggested this information could indicate the species is likely present in more areas to the north and south of where it is currently known.

Our Response: We incorporated the results of Hotaling et al. 2017 into this final listing rule. A review of satellite imagery indicates there may be some patches of permanent snow/ice (and thus potential western glacier stonefly habitat) in the Wyoming and Wind River ranges of Wyoming, south of Grand Teton National Park. However, we are not aware of any surveys that have been conducted in that area. The USGS has sampled in some areas between Grand Teton National Park/Beartooth and Glacier National Park, but have not documented western glacier stoneflies in that area. An increase in western glacier stonefly redundancy across their range is expected to help the species survive catastrophic events. However, the primary threat to western glacier stonefly habitat is habitat degradation and fragmentation from climate change. We expect climate change to have similar, negative effects on western glacier stonefly habitat rangewide. Thus, increased redundancy, in this case, is not expected to translate into increased resiliency or increased species viability. In addition, we must base our listing determination on the best available scientific and commercial information, and we have no information that western glacier stonefly occur in other areas than where the species is currently known.

Public Comments

(10) Comment: One public commenter noted an interest in seeing more information obtained and reviewed in regard to obtaining a better understanding of the true extent of stonefly habitat, the consequences of these species being listed on GNP's visitation and infrastructure, and what measures may be taken on a local level to help these species survive and grow in order to prevent economic and other hardships that come with listing.

Our Response: According to the Act, we must base our determination on the best available scientific information. We included the results of the most recent status review of meltwater lednian and western glacier stonefly (i.e., Giersch et al. 2017) in this final listing rule in our Factor A analyses. The Service is not allowed to consider economic impacts in our determination on whether to list a species under the Act. However, we believe that those impacts would be minimal, given the limited overlap of stonefly habitats with areas of visitor use and park infrastructure. Conservation measures are addressed in this document below under “Available Conservation Measures.”

(11) Comment: One commenter expressed support for listing both stonefly species and provided a link to a scientific journal article describing a 75 percent decline in winged insects in Germany over the past 27 years.

Our Response: The scientific information in the provided journal article indicates a long-term decline in a suite of winged insects in Germany. However, the insects in this study did not have an aquatic life-history component like both meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly, and occupied much different habitat types. Further, climate variables were not found to be significant drivers of the documented insect biomass decline. Thus, we did not find the results from the provided study informative to trend observations of stoneflies. Therefore, we did not include information from the provided study in our assessment of either stonefly species. Rather, we considered studies specific to meltwater lednian stonefly, western glacier stonefly, and other more closely related species in similar geographic areas to be the best available scientific information on which to base our assessment.

(12) Comment: Two joint commenters expressed support for listing both stonefly species and provided multiple scientific journal articles for the Service to assess.

Our Response: Of the 10 scientific articles provided, 3 (Jordan et al. 2016; Giersch et al. 2016; Treanor et al. 2013) were already included and cited in the proposed listing rule. Three of the other articles provided (Hotaling et al. 2017a; Clark et al. 2015; Leppi et al. 2012) were added to the final listing rule in our Factors A and E analyses. The remaining four articles (Hotaling et al. 2017b; Wuebbles et al. 2017; Chang and Hansen 2015; Al-Chokhacky et al. 2013) were broad in nature (large-scale climate information relevant to other ecosystems and species) and were not included in the final listing rule because we had finer scale information more relevant to western glacier stonefly and meltwater lednian stonefly and their habitats.

Determination of Western Glacier Stonefly and Meltwater Lednian Stonefly Status

Status Throughout All of Its Range

We find that the meltwater lednian stonefly is likely to become endangered throughout all of its range within the foreseeable future. The meltwater lednian stonefly occupies a relatively narrow range of alpine habitats that are expected to become fragmented and degraded by climate change, based on empirical glacier melting rates. Meltwater stonefly habitat is likely to be impacted by several factors that are expected to reduce the overall viability of the species to the point that it meets the definition of a threatened species.

We also find that the western glacier stonefly is likely to become endangered throughout all of its range within the foreseeable future. Similar to meltwater lednian stonefly, the western glacier stonefly occupies a relatively narrow range of alpine habitats that are expected to become fragmented and degraded by climate change, based on empirical glacier melting rates. In addition, decreasing distribution of western glacier stonefly has been documented in GNP. Western glacier stonefly habitat is likely to be impacted by several factors that are expected to reduce the overall viability of the species to the point that it meets the definition of a threatened species. Therefore, on the basis of the best available scientific and commercial information, we are listing the meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly as threatened species in accordance with sections 3(6) and 4(a)(1) of the Act.

We find that an endangered species status is not appropriate for the meltwater lednian stonefly because the species is not currently in danger of extinction as it faces relatively low near-term risk of extinction. Although the effects of climate change and drought are currently affecting, and expected to continue affecting, the alpine habitats occupied by the meltwater lednian stonefly, meltwater sources are expected to persist in the form of alpine springs and glacial lake outlets after the projected melting of most glaciers in GNP by 2030. Densities and estimated abundance of the meltwater lednian stonefly are currently relatively high. In addition, some habitats that are supplied by seasonal snowpack continue to be occupied by meltwater lednian stonefly. These findings suggest that, as climate change continues to impact stonefly habitat, some populations will likely persist in refugia areas at least through the foreseeable future.

We also find that an endangered species status is not appropriate for the western glacier stonefly because the species is not currently in danger of extinction as it faces relatively low near-term risk of extinction. Although the effects of climate change and drought are currently affecting, and expected to continue affecting, the alpine habitats occupied by the western glacier stonefly, meltwater sources are expected to persist in the form of alpine springs and glacial lake outlets after the projected melting of most glaciers in GNP by 2030. Although only 16 streams are known to be occupied by western glacier stonefly, densities and estimated abundance of the western glacier stonefly are currently relatively high in many streams. These findings suggest that, as climate change continues to impact stonefly habitat, some populations will likely persist in refugia areas at least through the foreseeable future.