AGENCY:

Office of Labor-Management Standards, Department of Labor.

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

In this rule, the Department revises the forms required by labor organizations under the Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act (“LMRDA” or “Act”). Under the rule, specified labor organizations file annual reports (Form T-1) concerning trusts in which they are interested. This document also sets forth the Department's review of and response to comments on the proposed rule. Under this rule, the Department requires a labor organization with total annual receipts of $250,000 or more (and, which therefore is obligated to file a Form LM-2 Labor Organization Annual Report) to also file a Form T-1, under certain circumstances, for each trust of the type defined by section 3(l) of the LMRDA (defining “trust in which a labor organization is interested”). Such labor organizations will trigger the Form T-1 reporting requirements, subject to certain exemptions, where the labor organization during the reporting period, either alone or in combination with other labor organizations, selects or appoints the majority of the members of the trust's governing board or contributes more than 50 percent of the trust's receipts. When applying this financial or managerial dominance test, contributions made pursuant to a collective bargaining agreement (CBA) shall be considered the labor organization's contributions. The rule provides appropriate instructions and revises relevant sections relating to such reports. The Department issues the rule pursuant to section 208 of the LMRDA.

DATES:

This rule is effective April 6, 2020; however, no labor organization is required to file a Form T-1 until 90 days after the conclusion of its first fiscal year that begins on or after June 4, 2020. A Form T-1 covers a trust's most recently concluded fiscal year, and a Form T-1 is required only for trusts whose fiscal year begins on or after June 4, 2020. A trust's “most recently concluded fiscal year” is the fiscal year beginning on or before 90 days before the filing union's fiscal year.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Andrew Davis, Chief of the Division of Interpretations and Standards, Office of Labor-Management Standards, U.S. Department of Labor, 200 Constitution Avenue NW, Room N-5609, Washington, DC 20210, (202) 693-0123 (this is not a toll-free number), (800) 877-8339 (TTY/TDD), OLMS-Public@dol.gov.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

The following is the outline of this discussion.

I. Statutory Authority

II. Background

A. Introduction

B. The LMRDA's Reporting and Other Requirements

C. History of the Form T-1

III. Summary and Explanation of the Final Rule

A. Overview of the Rule

B. Policy Justification

IV. Review of Proposed Rule and Comments Received

A. Overview of Comments

B. Policy Justifications

C. Employer Contributions/Taft-Hartley Plans

D. Issues Concerning Multi-Union Trusts

E. ERISA Exemption

F. Other Exemptions

G. Objections to Exemptions

H. Burden on Unions and Confidentiality Issues

I. Legal Support for Rule

V. Regulatory Procedures

A. Paperwork Reduction Act

B. Executive Orders 12866 and 13563

C. Regulatory Flexibility Act

D. Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act

VI. Text of Final Rule

VII. Appendix

I. Statutory Authority

The Department's statutory authority is set forth in section 208 of the Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act (LMRDA), 29 U.S.C. 438. Section 208 of the LMRDA provides that the Secretary of Labor shall have authority to issue, amend, and rescind rules and regulations prescribing the form and publication of reports required to be filed under the Act and such other reasonable rules and regulations as he may find necessary to prevent the circumvention or evasion of the reporting requirements in private sector labor unions.[1] This statutory authority also extends to federal public sector labor unions through both the Civil Service Reform Act of 1978 (CSRA), 5 U.S.C. 7120, “Standards of Conduct” regulations at 29 CFR part 458, and the Foreign Service Act of 1980 (FSA).

The Secretary has delegated his authority under the LMRDA to the Director of the Office of Labor-Management Standards and permitted re-delegation of such authority. See Secretary's Order 03-2012 (Oct. 19, 2012), published at 77 FR 69375 (Nov. 16, 2012).

Section 208 allows the Secretary to issue “reasonable rules and regulations (including rules prescribing reports concerning trusts in which a labor organization is interested) as he may find necessary to prevent the circumvention or evasion of [the Act's] reporting requirements.” 29 U.S.C. 438.

Section 3(l) of the LMRDA, 29 U.S.C. 402(l) provides that a “Trust in which a labor organization is interested' means a trust or other fund or organization (1) which was created or established by a labor organization, or one or more of the trustees or one or more members of the governing body of which is selected or appointed by a labor organization, and (2) a primary purpose of which is to provide benefits for the members of such labor organization or their beneficiaries.”

The authority to prescribe rules relating to section 3(l) trusts augments the Secretary's general authority to prescribe the form and publication of other reports required to be filed under the LMRDA. Section 201 of the Act requires unions to file annual, public reports with the Department, detailing the union's cash flow during the reporting period, and identifying its assets and liabilities, receipts, salaries and other direct or indirect disbursements to each officer and all employees receiving $10,000 or more in aggregate from the union, direct or indirect loans (in excess of $250 aggregate) to any officer, employee, or member, any loans (of any amount) to any business enterprise, and other disbursements. 29 U.S.C. 431(b). The statute requires that such information shall be filed “in such detail as may be necessary to disclose [a union's] financial conditions and operations.” Id. Large unions report this information on the Form LM-2. Smaller unions report less detailed information on the Form LM-3 or LM-4.

II. Background

A. Introduction

On May 30, 2019 the Department proposed to establish a Form T-1 Trust Annual Report to capture financial information pertinent to “trusts in which a labor organization is interested” (“section 3(l) trusts”). See 84 FR 25130. Historically, this information has largely gone unreported despite the significant impact such trusts have on labor organization financial operations and union members' own interests. This proposal was part of the Department's continuing effort to better effectuate the reporting requirements of the LMRDA.

The LMRDA's various reporting provisions are designed to empower labor organization members by providing them the means to maintain democratic control over their labor organizations and ensure a proper accounting of labor organization funds. Labor organization members are better able to monitor their labor organization's financial affairs and to make informed choices about the leadership of their labor organization and its direction when labor organizations disclose financial information as required by the LMRDA. By reviewing a labor organization's financial reports, a member may ascertain the labor organization's priorities and whether they are in accord with the member's own priorities and those of fellow members. At the same time, this transparency promotes both the labor organization's own interests as a democratic institution and the interests of the public and the government. Furthermore, the LMRDA's reporting and disclosure provisions, together with the fiduciary duty provision, 29 U.S.C. 501, which directly regulates the primary conduct of labor organization officials, operate to safeguard a labor organization's funds from depletion by improper or illegal means. Timely and complete reporting also helps deter labor organization officers or employees from embezzling or otherwise making improper use of such funds.

The rule helps bring the reporting requirements for labor organizations and section 3(l) trusts in line with contemporary expectations for the disclosure of financial information. Today, labor organizations are more complex in their structure and scope than labor organizations of the past. In reaction to an increasingly global, complicated, and sophisticated marketplace, unions must leverage significant financial capital to hire professional economic, financial, legal, political and public relations expertise not readily or traditionally on hand. See Marick F. Masters, Unions at the Crossroads: Strategic Membership, Financial, and Political Perspectives 34 (1997).

Labor organization members, no less than consumers, citizens, or creditors, expect access to relevant and useful information in order to make fundamental investment, career, and retirement decisions, evaluate options, and exercise legally guaranteed rights.

B. The LMRDA's Reporting and Other Requirements

In enacting the LMRDA in 1959, a bipartisan Congress made the legislative finding that in the labor and management fields “there have been a number of instances of breach of trust, corruption, disregard of the rights of individual employees, and other failures to observe high standards of responsibility and ethical conduct which require further and supplementary legislation that will afford necessary protection of the rights and interests of employees and the public generally as they relate to the activities of labor organizations, employers, labor relations consultants, and their officers and representatives.” 29 U.S.C. 401(b). The statute was designed to remedy these various ills through a set of integrated provisions aimed at labor organization governance and management. These include a “bill of rights” for labor organization members, which provides for equal voting rights, freedom of speech and assembly, and other basic safeguards for labor organization democracy, see 29 U.S.C. 411-415; financial reporting and disclosure requirements for labor organizations, their officers and employees, employers, labor relations consultants, and surety companies, see 29 U.S.C. 431-436, 441; detailed procedural, substantive, and reporting requirements relating to labor organization trusteeships, see 29 U.S.C. 461-466; detailed procedural requirements for the conduct of elections of labor organization officers, see 29 U.S.C. 481-483; safeguards for labor organizations, including bonding requirements, the establishment of fiduciary responsibilities for labor organization officials and other representatives, criminal penalties for embezzlement from a labor organization, a prohibition on certain loans by a labor organization to officers or employees, prohibitions on employment by a labor organization of certain convicted felons, and prohibitions on payments to employees, labor organizations, and labor organization officers and employees for prohibited purposes by an employer or labor relations consultant, see 29 U.S.C. 501-505; and prohibitions against extortionate picketing, retaliation for exercising protected rights, and deprivation of LMRDA rights by violence, see 29 U.S.C. 522, 529, 530.

The LMRDA was the direct outgrowth of a Congressional investigation conducted by the Select Committee on Improper Activities in the Labor or Management Field, commonly known as the McClellan Committee, chaired by Senator John McClellan of Arkansas. In 1957, the committee began a highly publicized investigation of labor organization racketeering and corruption; and its findings of financial abuse, mismanagement of labor organization funds, and unethical conduct provided much of the impetus for enactment of the LMRDA's remedial provisions. See generally Benjamin Aaron, The Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959, 73 Harv. L. Rev. 851, 851-55 (1960).

During the investigation, the committee uncovered a host of improper financial arrangements between officials of several international and local labor organizations and employers (and labor consultants aligned with the employers) whose employees were represented by the labor organizations in question or might be organized by them. Similar arrangements were also found to exist between labor organization officials and the companies that handled matters relating to the administration of labor organization benefit funds. See generally Interim Report of the Select Committee on Improper Activities in the Labor or Management Field, S. Report No. 85-1417 (1957); see also William J. Isaacson, Employee Welfare and Benefit Plans: Regulation and Protection of Employee Rights, 59 Colum. L. Rev. 96 (1959).

Financial reporting and disclosure were conceived as partial remedies for these improper practices. As noted in a key Senate Report on the legislation, disclosure would discourage questionable practices (“The searchlight of publicity is a strong deterrent.”), aid labor organization governance (labor organizations will be able “to better regulate their own affairs” because “members may vote out of office any individual whose personal financial interests conflict with his duties to members”), facilitate legal action by members for fiduciary violations (against “officers who violate their duty of loyalty to the members”), and create a record (“the reports will furnish a sound factual basis for further action in the event that other legislation is required”). S. Rep. No. 187 (1959) 16 reprinted in 1 NLRB Legislative History of the Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959, 412.

The Department has developed several forms for implementing the LMRDA's financial reporting requirements. The annual reports required by section 201(b) of the Act, 29 U.S.C. 431(b) (Form LM-2, Form LM-3, and Form LM-4), contain information about a labor organization's assets, liabilities, receipts, disbursements, loans to officers and employees and business enterprises, payments to each officer, and payments to each employee of the labor organization paid more than $10,000 during the fiscal year. The reporting detail required of labor organizations, as the Secretary has established by rule, varies depending on the amount of the labor organization's annual receipts. 29 CFR 403.4.

The labor organization's president and treasurer (or its corresponding officers) are personally responsible for filing the reports and for any statement in the reports known by them to be false. 29 CFR 403.6. These officers are also responsible for maintaining records in sufficient detail to verify, explain, or clarify the accuracy and completeness of the reports for not less than five years after the filing of the forms. 29 CFR 403.7. A labor organization “shall make available to all its members the information required to be contained in such reports” and “shall. . .permit such member[s] for just cause to examine any books, records, and accounts necessary to verify such report[s].” 29 CFR 403.8(a).

The reports are public information. 29 U.S.C. 435(a). The Secretary is charged with providing for the inspection and examination of the financial reports, 29 U.S.C. 435(b). For this purpose, OLMS maintains: (1) A public disclosure room where copies of such reports filed with OLMS may be reviewed and; (2) an online public disclosure site, where copies of such reports filed since the year 2000 are available for the public's review.

C. History of the Form T-1

The Form T-1 report was first proposed on December 27, 2002, as one part of a proposal to extensively change the Form LM-2. 67 FR 79280 (Dec. 27, 2002). The rule was proposed under the authority of Section 208, which permits the Secretary to issue such rules “prescribing reports concerning trusts in which a labor organization is interested” as he may “find necessary to prevent the circumvention or evasion of [the LMRDA's] reporting requirements.” 29 U.S.C. 438. Following consideration of public comments, on October 9, 2003, the Department published a final rule enacting extensive changes to the Form LM-2 and establishing a Form T-1. 68 FR 58374 (Oct. 9, 2003) (2003 Form T-1 rule). The 2003 Form T-1 rule eliminated the requirement that unions report on subsidiary organizations on the Form LM-2, but it mandated that each labor organization filing a Form LM-2 report also file a separate report to “disclose assets, liabilities, receipts, and disbursements of a significant trust in which the labor organization is interested.” 68 FR at 58477. The reporting labor organization would make this disclosure by filing a separate Form T-1 for each significant trust in which it was interested. Id. at 58524.

To conform to the statutory requirement that trust reporting is “necessary to prevent the circumvention or evasion of [the LMRDA's] reporting requirements,” the 2003 Form T-1 rule developed the “significant trust in which the labor organization is interested” test. It used the section 3(l) statutory definition of “a trust in which a labor organization is interested” coupled with an administrative determination of when a trust is deemed “significant.” 68 FR at 58477-78. The LMRDA defines a “trust in which a labor organization is interested” as a trust or other fund or organization (1) which was created or established by a labor organization, or one or more of the trustees or one or more members of the governing body of which is selected or appointed by a labor organization, and (2) a primary purpose of which is to provide benefits for the members of such labor organization or their beneficiaries. Id. (29 U.S.C. 402(l)).

The 2003 Form T-1 rule set forth an administrative determination that stated that a “trust will be considered significant” and therefore subject to the Form T-1 reporting requirement under the following conditions:

(1) The labor organization had annual receipts of $250,000 or more during its most recent fiscal year, and (2) the labor organization's financial contribution to the trust or the contribution made on the labor organization's behalf, or as a result of a negotiated agreement to which the labor organization is a party, is $10,000 or more annually. Id. at 58478.

The portions of the 2003 rule relating to the Form T-1 were vacated by the D.C. Circuit in AFL-CIO v. Chao, 409 F.3d at 389-391. The court held that the form “reaches information unrelated to union reporting requirements and mandates reporting on trusts even where there is no appearance that the union's contribution of funds to an independent organization could circumvent or evade union reporting requirements by, for example, permitting the union to maintain control of the funds.” Id. at 389. The court also vacated the Form T-1 portions of the 2003 rule because its significance test failed to establish reporting based on domination or managerial control of assets subject to LMRDA Title II jurisdiction.

The court reasoned that the Department failed to explain how the test—i.e., selection of one member of a board and a $10,000 contribution to a trust with $250,000 in receipts—could give rise to circumvention or evasion of Title II reporting requirements. Id. at 390. In so holding, the court emphasized that Section 208 authority is the only basis for LMRDA trust reporting, that this authority is limited to preventing circumvention or evasion of Title II reporting, and that “the statute doesn't provide general authority to require trusts to demonstrate that they operate in a manner beneficial to union members.” Id. at 390.

However, the court recognized that reports on trusts that reflect a labor organization's financial condition and operations are within the Department's rulemaking authority, including trusts “established by one or more unions or through collective bargaining agreements calling for employer contributions, [where] the union has retained a controlling management role in the organization,” and also those “established by one or more unions with union members' funds because such establishment is a reasonable indicium of union control of that trust.” Id. The court acknowledged that the Department's findings in support of its rule were based on particular situations where reporting about trusts would be necessary to prevent evasion of the related labor organizations' own reporting obligations. Id. at 387-88. One example included a situation where “trusts [are] funded by union members' funds from one or more unions and employers, and although the unions retain a controlling management role, no individual union wholly owns or dominates the trust, and therefore the use of the funds is not reported by the related union.” Id. at 389 (emphasis added). In citing these examples, the court explained that “absent circumstances involving dominant control over the trust's use of union members' funds or union members' funds constituting the trust's predominant revenues, a report on the trust's financial condition and operations would not reflect on the related union's financial condition and operations.” Id. at 390. For this reason, while acknowledging that there are circumstances under which the Secretary may require a report, the court disapproved of a broader application of the rule to require reports by any labor organization simply because the labor organization satisfied a reporting threshold (a labor organization with annual receipts of at least $250,000 that contributes at least $10,000 to a section 3(l) trust with annual receipts of at least $250,000). Id.

In light of the decision by the D.C. Circuit and guided by its opinion, the Department issued a revised Form T-1 final rule on September 29, 2006. 71 FR 57716 (Sept. 29, 2006) (2006 Form T-1 rule). The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia vacated this rule due to a failure to provide a new notice and comment period. AFL-CIO v. Chao, 496 F. Supp. 2d 76 (D.D.C. 2007). The district court did not engage in a substantive review of the 2006 rule, but the court noted that the AFL-CIO demonstrated that “the absence of a fresh comment period . . . constituted prejudicial error” and that the AFL-CIO objected with “reasonable specificity” to warrant relief vacating the rule. Id. at 90-92.

The Department issued a proposed rule for a revised Form T-1 on March 4, 2008. 73 FR 11754 (Mar. 4, 2008). After notice and comment, the 2008 Form T-1 final rule was issued on October 2, 2008. 73 FR 57412. The 2008 Form T-1 rule took effect on January 1, 2009. Under that rule, Form T-1 reports would have been filed no earlier than March 31, 2010, for fiscal years that began no earlier than January 1, 2009.

Pursuant to AFL-CIO v. Chao, the 2008 Form T-1 rule stated that labor organizations with total annual receipts of $250,000 or more must file a Form T-1 for those section 3(l) trusts in which the labor organization, either alone or in combination with other labor organizations, had management control or financial dominance. 73 FR at 57412. For purposes of the rule, a labor organization had management control if the labor organization alone, or in combination with other labor organizations, selected or appointed the majority of the members of the trust's governing board. Further, for purposes of the rule, a labor organization had financial dominance if the labor organization alone, or in combination with other labor organizations, contributed more than 50 percent of the trust's receipts during the annual reporting period. Significantly, the rule treated contributions made to a trust by an employer pursuant to CBA as constituting contributions by the labor organization that was party to the agreement.

Additionally, the 2008 Form T-1 rule provided exemptions to the Form T-1 filing requirements. No Form T-1 was required for a trust: Established as a political action committee (PAC) fund if publicly available reports on the PAC fund were filed with Federal or state agencies; established as a political organization for which reports were filed with the IRS under section 527 of the IRS code; required to file a Form 5500 under ERISA; or constituting a federal employee health benefit plan that was subject to the provisions of the Federal Employees Health Benefits Act (FEHBA), 5 U.S.C. 8901 et seq. Similarly, the rule clarified that no Form T-1 was required for any trust that met the statutory definition of a labor organization, 29 U.S.C. 402(i), and filed a Form LM-2, Form LM-3, or Form LM-4 or was an entity that the LMRDA exempts from reporting. Id.

In the Spring and Fall 2009 Regulatory Agenda, the Department announced its intention to rescind the Form T-1. It also indicated that it would return reporting of wholly owned, wholly controlled, and wholly financed (“subsidiary”) organizations to the Form LM-2 or LM-3 reports. On December 3, 2009, the Department issued a notice of proposed extension of filing due date to delay for one calendar year the filing due dates for Form T-1 reports required to be filed during calendar year 2010. 74 FR 63335. On December 30, 2009, following notice and comment, the Department published a rule extending for one year the filing due date of all Form T-1 reports required to be filed during calendar year 2010. 74 FR 69023.

Subsequently, on February 2, 2010, the Department published a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) proposing to rescind the Form T-1. 75 FR 5456. After notice and comment, the Department published the final rule on December 1, 2010. In its rescission, the Department stated that it considered the reporting required under the rule to be overly broad and not necessary to prevent circumvention or evasion of Title II reporting requirements. The Department concluded that the scope of the 2008 Form T-1 rule was overbroad because it covered many trusts, such as those funded by employer contributions, without an adequate showing that reporting for such trusts is necessary to prevent the circumvention or evasion of the Title II reporting requirements. See 75 FR 74936.

III. Summary and Explanation of the Final Rule

A. Overview of the Rule

This rule requires a labor organization with total annual receipts of $250,000 or more to file a Form T-1, under certain circumstances, for each trust of the type defined by section 3(l) of the LMRDA, 29 U.S.C. 402(l) (defining “trust in which a labor organization is interested”). Such labor organizations trigger the Form T-1 reporting requirements where the labor organization during the reporting period, either alone or in combination with other labor organizations, (1) selects or appoints the majority of the members of the trust's governing board, or (2) contributes more than 50 percent of the trust's receipts. When applying this financial or managerial dominance test, contributions made pursuant to a CBA are considered the labor organization's contributions. As explained further below, this test was tailored to be consistent with the court's holding in AFL-CIO v. Chao, 409 F.3d 377, 389-391 (D.C. Cir. 2005), as well as the 2008 final Form T-1 rule.

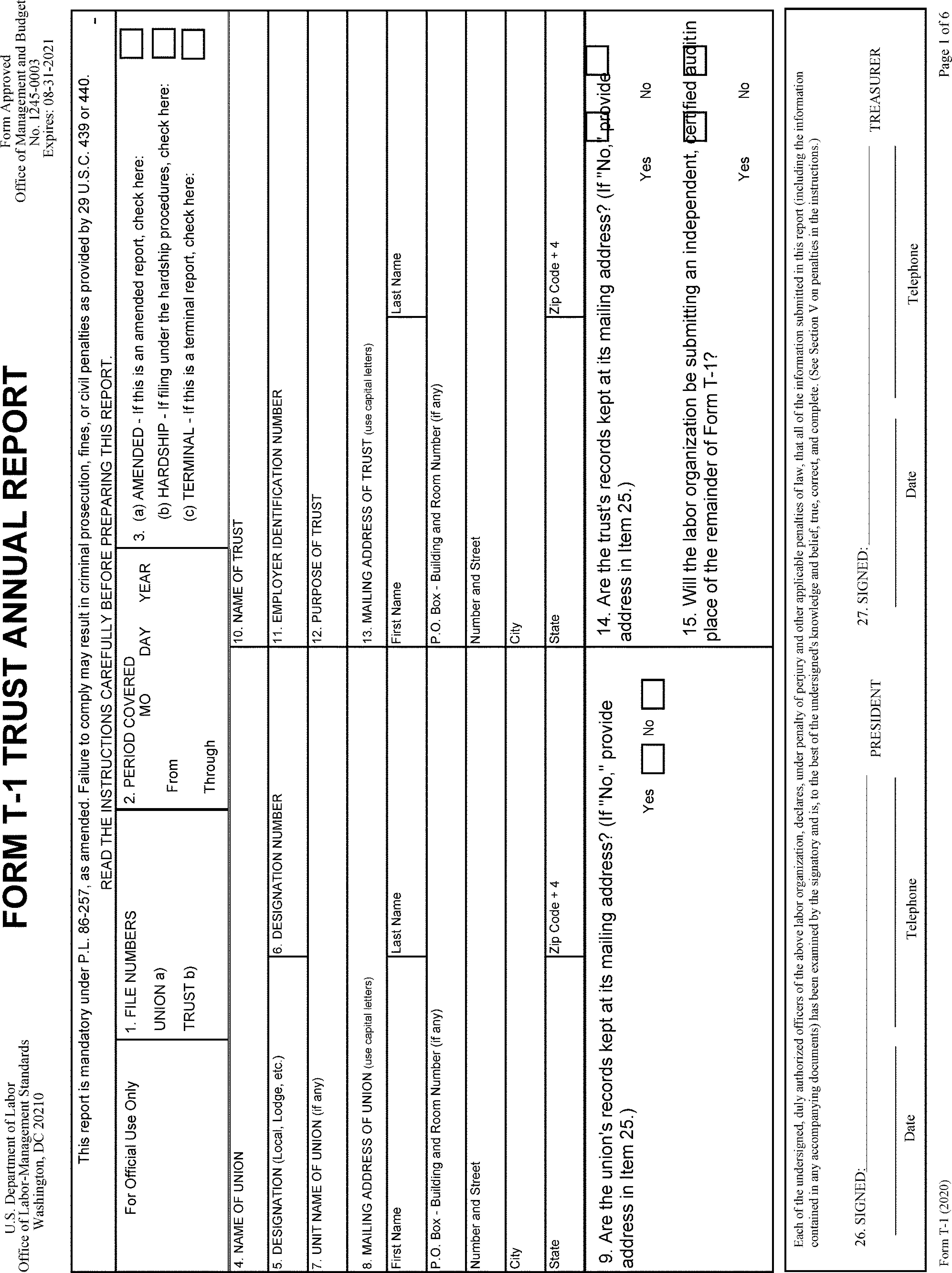

The Form T-1 uses the same basic template as prescribed for the Form LM-2. Both forms require the labor organization to provide specified aggregated and disaggregated information relating to the financial operations of the labor organization and the trust. Typically, a labor organization is required to provide information on the Form T-1 explaining certain transactions by the trust (such as disposition of property by other than market sale, liquidation of debts, loans or credit extended on favorable terms to officers and employees of the labor organization); and identifying major receipts and disbursements by the trust during the reporting period. The Form T-1, however, is shorter and requires less information than the Form LM-2. The Form T-1, unlike the Form LM-2, does not require that receipts and disbursements be identified by functional category.

The Form T-1 includes: 14 questions that identify the trust; six yes/no questions covering issues such as whether any loss or shortage of funds was discovered during the reporting year and whether the trust had made any loans to officers or employees of the labor organizations, which were granted at more favorable terms than were available to others; statements regarding the total amount of assets, liabilities, receipts and disbursements of the trust; a schedule that separately identifies any individual or entity from which the trust receives $10,000 or more, individually or in the aggregate, during the reporting period; a schedule that separately identifies any entity or individual that received disbursements that aggregate to $10,000 or more, individually or in the aggregate, from the trust during the reporting period and the purpose of disbursement; and a schedule of disbursements to officers and employees of the trust who received more than $10,000.

Two threshold requirements that were contained in the 2003 and 2006 rules, but not the 2008 rule, relating to the amount of a labor organization's contributions to a trust ($10,000 per annum) and the amount of the contributions received by a trust ($250,000 per annum) are not included in the rule. The Department believes that, consistent with the D.C. Circuit's AFL-CIO v. Chao decision, the labor organization's control over the trust either alone or with other labor organizations, measured by its selection of a majority of the trust's governing body or its majority share of receipts during the reporting period, provides the appropriate gauge for determining whether a Form T-1 must be filed by the participating labor organization.

Under the rule, exemptions are provided for labor organizations with section 3(l) trusts where the trust, as a political action committee (“PAC”) or a political organization (the latter within the meaning of 26 U.S.C. 527), submits timely, complete and publicly available reports required of them by federal or state law with government agencies; federal employee health benefit plans subject to the provision of the Federal Employees Health Benefits Act (FEHBA); or any for-profit commercial bank established or operating pursuant to the Bank Holding Act of 1956, 12 U.S.C. 1843. The Department also exempts credit unions from Form T-1 disclosure, as explained further below. Similarly, no Form T-1 is required for any trust that meets the statutory definition of a labor organization and files a Form LM-2, Form LM-3, or Form LM-4 or is an entity that the LMRDA exempts from reporting. Consistent with the 2008 rule, but in contrast to the 2003 and 2006 rules, today's rule includes an exemption for section 3(l) trusts that are part of employee benefit plans that file a Form 5500 Annual Return/Report under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (“ERISA”). Additionally, a partial exemption is provided for a trust for which an audit was conducted in accordance with prescribed standards and the audit is made publicly available. A labor organization choosing to use this option must complete and file the first page of the Form T-1 and a copy of the audit.

Also, unlike the 2008 rule, the Department exempts unions from reporting on the Form T-1 their subsidiary organizations, retaining the requirement that unions must report their subsidiaries on the union's Form LM-2 report. See Part X of the Form LM-2 instructions (defining a “subsidiary organization” as “any separate organization of which the ownership is wholly vested in the reporting labor organization or its officers or its membership, which is governed or controlled by the officers, employees, or members of the reporting labor organization, and which is wholly financed by the reporting labor organization.”).

Also, unlike the 2008 rule, the Department permits the parent union (i.e., the national/international or intermediate union) to file the Form T-1 report for covered trusts in which both the parent union and its affiliates meet the financial or managerial domination test.[2] The affiliates must continue to identify the trust in their Form LM-2 report, and also state in their Form LM-2 report that the parent union will file a Form T-1 report for the trust. The Department will also allow a single union to voluntarily file the Form T-1 on behalf of itself and the other unions that collectively contribute to a multiple-union trust, relieving the Form T-1 obligation on other unions.

This final rule also differs in three specific respects from the proposed rule in response to concerns raised by commenters. These features of the rule are related above, but merit specific recognition here as determinations made by the Department subsequent to the published NPRM. First, unions need not file for trusts that operate as credit unions. Second, the Department will allow a union to voluntarily file the Form T-1 on behalf of one or more other unions where each of those unions would otherwise be obligated to individually file for the same trust. Third, the trust's fiscal year that the union must report on has been changed. Under the proposed rule, the union would have reported on trusts whose most recent fiscal year ended on or before the union's fiscal year. Under the current rule, the union will report on trusts whose most recent fiscal year ended 90 or more days before the end of the union's fiscal year.

B. Policy Justification

The Form T-1 closes a reporting gap whereby labor organizations are required to report only on the funds that they exclusively control, but not those funds over which they exercise domination. As a result, this rule helps prevent the circumvention or evasion of the LMRDA's reporting requirements. Further, this rule is designed to provide labor organization members a proper accounting of how their labor organization's funds are invested or otherwise expended by the trust. Such disclosure helps deter fraud and corruption involving such trusts. Labor organization members have an interest in obtaining information about a labor organization's funds provided to a trust for the member's particular or collective benefit whether solely administered by the labor organization or a separate, jointly administered governing board. Also, because the money an employer contributes to such trusts pursuant to a CBA might otherwise have been paid directly to a labor organization's members in the form of increased wages and benefits, the members on whose behalf the financial transaction was negotiated have an interest in knowing what funds were contributed, how the money was managed, and how it was spent.

In terms of preventing the circumvention or evasion of the LMRDA's reporting requirements, the rule will make it more difficult for a labor organization to avoid, simply by transferring money from the labor organization to a trust, the basic reporting obligation that applies if the funds had been retained by the labor organization. Although the rule will not require a Form T-1 to be filed for all section 3(l) trusts in which a labor organization participates, it will be required where a labor organization, alone or in combination with other labor organizations, appoints or selects a majority of the members of the trust's governing board or where contributions by labor organizations, or by employers pursuant to a CBA, represent greater than 50 percent of the revenue of the trust.

Thus, the rule follows the instruction in AFL-CIO v. Chao, where the D.C. Circuit concluded that the Secretary had shown that trust reporting was necessary to prevent evasion or circumvention where “trusts [are] established by one or more unions with union members' funds because such establishment is a reasonable indicium of union control of the trust,” as well as where there are characteristics of “dominant union control over the trust's use of union members' funds or union members' funds constituting the trust's predominant revenues.” 409 F.3d at 389, 390.

As an illustration of how this check will work, consider an instance in which a Form T-1 identifies a $15,000 payment from the trust to a company for printing services. Under this rule, the labor organization must identify on the Form T-1 the company and the purpose of the payment. This information, coupled with information about a labor organization official's “personal business” interests in the printing company, a labor organization member or the Department may discover whether the official has reported this payment on a Form LM-30.[3]

Additional information from the labor organization's Form LM-2 might allow a labor organization member to ascertain whether the trust and the labor organization have used the same printing company and whether there was a pattern of payments by the trust and the labor organization from which an inference could be drawn that duplicate payments were being made for the same services.[4] Upon further inquiry into the details of the transactions, a member or the government might be able to determine whether the payments masked a kickback or other conflict-of-interest payment, and, as such, reveal an instance where the labor organization, a labor organization official, or an employer may have failed to comply with their reporting obligations under the Act. Furthermore, this rule will provide a missing piece to one part of the Department's system to crosscheck a labor organization's reported holdings and transactions by party, description, and reporting period and thereby helps identify deviations in the reported details, including instances where the reporting obligation appears reciprocal, but one or more parties have not reported the matter.

In reviewing submitted Form LM-2 reports, the Department located several instances in which labor organizations disbursed large sums of money to trusts. As an example, one local disbursed over $700,000 to one trust and over $1.2 million to another of its trusts, in fiscal year 2017. Also in 2017, a national labor organization disbursed almost $400,000 to one of its trusts. Several locals each reported on their FY 17 Form LM-2 reports varying ownership interests in a building corporation that owns the unions' hall. The Form T-1 requires that the labor organizations report the trusts' management of these disbursements and assets. By establishing reporting for their trusts comparable to that for their own funds, the Form T-1 will prevent the unions from circumventing or evading their reporting requirements, ensuring financial transparency for all funds dominated by the unions.

Additionally, as stated, the Form T-1 will establish a deterrent effect on potential labor-management fraud and corruption. Labor organization officials and trustees owe a fiduciary duty to both their labor organization and the trust, respectively. Nevertheless, there are examples of embezzlement of funds held by both labor organizations and their section 3(l) trusts.[5] By disclosing information to labor organization members—the true beneficiaries of such trusts—the Form T-1 will increase the likelihood that wrongdoing is detected and may deter individuals who might otherwise be tempted to divert funds from the trusts.

The following examples illustrate recent situations in which funds held in section 3(l) trusts have been used in a manner that, if subject to LMRDA reporting, could have been noticed by the members of the labor organization and would likely have been scrutinized by this Department: [6]

- In 2011, a former secretary for a union was convicted for embezzling $412,000 from the union and its apprenticeship and training fund.[7]

- In 2015, an employee of a union pled guilty to embezzling over $160,000 from a joint apprenticeship trust fund account that was used to train future union members.[8]

- In 2017, a former business manager and financial secretary for a union local pled guilty to charges that he embezzled between $250,000 and $550,000 in union funds from an operational account and from an apprentice fund.[9]

- In 2018, a former trustee of a trust fund for apprentice and journeyman education and training was sentenced for submitting a false reimbursement request in connection with training events. In his plea, the former trustee admitted that the amount owed to the training fund totaled $12,000.[10]

- In 2018, a union official was sentenced for illegally channeling funds from a union training center to union officials and employees for their personal use.[11]

Under the rule, each labor organization in these examples would have been required to file a Form T-1 because each of these funds is a 3(l) trust that meets the significant contribution test, as outlined in the rule. In each instance, the labor organization's contribution to the trust, including contributions made pursuant to a CBA, made alone or in combination with other labor organizations, represented greater than 50 percent of the trust's revenue in the one-year reporting period. The labor organizations would have been required to annually disclose for each trust the total value of its assets, liabilities, receipts, and disbursements. For each receipt or disbursement of $10,000 or more (whether individually or in the aggregate), the labor organization would have been required to provide: The name and business address of the individual or entity involved in the transaction(s), the type of business or job classification of the individual or entity; the purpose of the receipt or disbursement; its date, and amount. Further, the labor organization would have been required to provide additional information concerning any trust losses or shortages, the acquisition or disposition of any goods or property other than by purchase or sale; the liquidation, reduction, or write off of any liabilities without full payment of principal and interest, and the extension of any loans or credit to any employee or officer of the labor organization at terms that were granted at more favorable terms than were available to others, and any disbursements to officers and employees of the trust.

In developing this rule, the Department also relied, in part, on information it received from the public on previous proposals. In its comments on the 2006 proposal, a labor policy group identified multiple instances where labor organization officials were charged, convicted, or both, for embezzling or otherwise improperly diverting labor organization trust funds for their own gain, including the following: (1) Five individuals were charged with conspiring to steal over $70,000 from a local's severance fund; (2) two local labor organization officials confessed to stealing about $120,000 from the local's job training funds; (3) an employee of an international labor organization embezzled over $350,000 from a job training fund; (4) a local labor organization president embezzled an undisclosed amount from the local's disaster relief fund; and (5) a former international officer, who had also been a director and trustee of a labor organization benefit fund, was convicted of embezzling about $100,000 from the labor organization's apprenticeship and training fund. 71 FR 57716, 57722.

The comments received from labor organizations on previous proposals generally opposed any reporting obligation concerning trusts. By contrast, many labor organization members recommended generally greater scrutiny of labor organization trust funds. For example, in response to the Department's 2008 proposal, commenters included several members of a single international labor organization. They explained that under the labor organization's CBAs, the employer sets aside at least $.20 for each hour worked by a member and that this amount was paid into a benefit fund known as a “joint committee.” 71 FR 57716, 57722. The commenters asserted that some of the funds were “lavished on junkets and parties” and that the labor organization used the joint committees to reward political supporters of the labor organization's officials. They stated that the labor organization refused to provide information about the funds, including amounts paid to “union staff.” From the perspective of one member, the labor organization did not want “this conflict of interest” to be exposed. Id.

If the Department's rule had been in place, the members of the affected labor organizations, aided by the information disclosed in the labor organizations' Form T-1s, would have been in a much better position to discover any potential improper use of the trust funds and thereby minimize the injury to the trust. Further, the fear of discovery could have deterred the wrongdoers from engaging in any offending conduct in the first place.

The foregoing discussion provides the Department's rationale for the position that the Form T-1 rule will add necessary safeguards intended to deter circumvention or evasion of the LMRDA's reporting requirements. In particular, with the Form T-1 in place, it will be more difficult for labor organizations, employers, and union officers and employees to avoid the disclosure required by the LMRDA. Further, labor organization members will be able to review financial information they may not otherwise have had, empowering them to better oversee their labor organization's officials and finances.

IV. Review of Proposed Rule and Comments Received

A. Overview of Comments

The Department provided for a 60-day comment period ending July 29, 2019. 84 FR 25130. The Department received 35 comments on the Form T-1 proposed rule. Of these comments, all 35 were unique, but only 33 were substantive. The two remaining comments merely requested an extension of the comment period. The Department declined the extension requests by letter dated July 29, 2019.

Comments were received from labor organizations, employer associations, public interest groups, benefit funds and plans, accounting firms, members of Congress, and private individuals.

Of the 33 unique, substantive comments received, 15 expressed overall support for the proposed rule, 16 were generally opposed, and the remaining 2 comments were essentially neutral—focusing on a credit union exemption. The Department also received one late comment. Although not considered, the concerns raised were substantively addressed in the Department's responses to other timely-submitted comments.

Comments offering support for the proposed rule largely focused on the value of the rule in promoting financial transparency and union democracy and in curtailing union corruption. The primary concern expressed by this segment of commenters was that the Department not allow more than a few limited exemptions to the reporting requirement, if any. Some urged the Department not to adopt exemptions such as allowing parent unions to file on behalf of an affiliate when both are interested in the same trust, or even remove the union size threshold that limits the Form T-1 requirement to unions that currently file an annual Form LM-2 report.

Comments opposed to the NPRM largely focused on the additional reporting burden the Form T-1 would create for unions and the confidentiality concerns surrounding much of the itemization required by the Form T-1. The primary concerns advanced by these commenters were that the Department alleviate the redundancy of having each union report on a multi-union trust, include all proposed exemptions, and refrain from treating employer contributions to trust funds as union funds for any purpose. Commenters who opposed the Form T-1 also urged the Department to include exemptions beyond those contemplated in the NPRM, including exemptions for unions contributing a de minimis amount to a multi-union trust and for trusts that file the Form 990 with the IRS.

B. Policy Justifications

In the NPRM, the Department cited public disclosure and transparency of union finances as major benefits of and policy justifications for creating the Form T-1. A number of commenters approved of the Form T-1 as a means to increase union transparency. The Department agrees with these commenters that the fundamental reason the Form T-1 is necessary is to effectuate the level of transparency envisioned by Congress in drafting the LMRDA. In fact, those commenters who were generally opposed to this rule maintained only that the transparency benefits were outweighed by the costs involved, rather than claiming that preventing circumvention or evasion to ensure union financial transparency would not be a benefit to union members, the unions as organizations, and the public. One union commenter wrote, as part of expressing support for the proposed exemptions to the Form T-1 reporting obligation under the rule, that the union “invests significant resources to ensure that we are accountable to our members and that our financial operations are transparent, responsible, and compliant with applicable laws.”

Thus, the comments collectively illustrate there is a general consensus that public reporting of union finances and the transparency it provides is desirable for all parties. The Department promulgates this rule, in part, because the Department agrees with those commenters who stated that the greater financial transparency that this rule provides, and which serves the LMRDA purpose of preventing circumvention or evasion, outweighs the reporting burden and other costs of this rule.

Finally, the Department notes that, as the union commenter quoted above recognized, the Department has provided exemptions from the reporting requirement wherever doing so does not compromise the benefits of the rule's transparency and reduces reporting redundancy. Two examples are: The Form 5500 exemption, which recognizes that trusts filing that form already provide sufficient public disclosure; and the confidentiality exemption, which recognizes that there are privacy concerns that outweigh the benefit of additional transparency for itemized disbursements in a limited number of circumstances.

Additionally, in the NPRM, the Department cited specific instances of, and the general potential for, corruption on the part of union leadership or individual union officials or employees as a significant rationale for establishing the Form T-1. A number of commenters agreed, highlighting additional instances of union corruption as justifications for the rule. Commenters agreed that a substantial benefit of the financial transparency discussed above is that it will reveal and likely deter misuse of covered funds. Documented instances of union corruption, involving trusts and the opportunities for such while union-controlled funds' financial information remained unreported, make a strong case for this rule.

The Department notes that many commenters relied upon the same example of union corruption as the specific type of corruption which necessitates the Form T-1. Nine separate commenters discussed a training center trust fund corruption scandal involving employees of Fiat Chrysler and top union officials of the United Auto Workers (UAW). In 2018, an investigation of this auto industry corruption in Detroit, Michigan produced multiple criminal convictions in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan. The joint investigations conducted by OLMS, the Department of Labor's Office of Inspector General, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Internal Revenue Service focused on a conspiracy involving Fiat Chrysler executives bribing labor officials to influence labor negotiations. Their violations included conspiracy to violate the Labor Management Relations Act for paying and delivering over $1.5 million in prohibited payments and things of value to UAW officials, receiving prohibited payments and things of value from others acting in the interest of Fiat Chrysler, failing to report income on individual tax returns, conspiring to defraud the United States by preparing and filing false tax returns for the UAW-Chrysler National Training Center (NTC) that concealed millions of dollars in prohibited payments directed to UAW officials, and deliberately providing misleading and incomplete testimony in the federal grand jury.[12] These comments demonstrate that stakeholders are concerned about the problems caused by a lack of transparency, and that such corruption is not purely theoretical.

C. Employer Contributions/Taft-Hartley Plans

In the NPRM, the Department proposed a test for the degree of union control of a trust as the basis for applying the Form T-1 reporting obligation. This test has a managerial dominance prong and a financial dominance prong. As part of the test, the Department proposed that employer contributions to a trust made pursuant to a CBA with the union count as union contributions for purposes of determining financial dominance. This final rule adopts the test.

The rule's provision that employer contributions made pursuant to a CBA constitute union contributions will likely lead to a number of unions reporting joint union and employer trusts, known as Taft-Hartley trusts, on their Form T-1 reports. These trusts are expressly permitted by section 302 of the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, 29 U.S.C. 186, and are designed to be managed by a board of trustees on which the union and employer are equally represented. The funding for these trusts typically comes from employer contributions under a negotiated CBA. Generally speaking, these trusts are designed to provide employee benefits, such as pensions. In addition to the requirement that these trusts be managed by a board of equal union and employer representation, these trusts are subject to specific regulatory requirements under the Taft-Hartley Act, and many of these trusts report under ERISA as well.

Several commenters who objected to the Department applying the Form T-1 reporting obligation to Taft-Hartley trusts claimed that the Taft-Hartley Act provides sufficient protection against union or union agent misuse of the funds. These commenters pointed to three particular requirements they believe adequately protect the funds in these trusts such that T-1 reporting is not necessary. First, the trust must be legally separate from the union. Second, such trusts are administered by boards on which union(s) and employer(s) involved in the trusts are equally represented. Third, Taft-Hartley trusts are subjected to an annual independent audit.

As to the trust being a legally and functionally separate entity, the Department does not consider this sufficient either to prevent evasion or circumvention of LMRDA reporting requirements or to eliminate the opportunity for corruption created by such evasion or circumvention. A union or individual bad actor might engage in corrupt activities to misdirect union funds with an entity wholly separate from the union. If union officers or employees have the authority to direct the union's funds, then whether the trust is a separate legal entity will not meaningfully reduce the potential for misuse of such funds. Reporting on such trusts, however, will help prevent the opportunity for such misuse of union funds. Where the funds are overseen by a board that includes union representatives and are meant to benefit union members, the opportunities for such corruption are apparent. A more “traditional” union trust, such as a multi-union building trust, is legally distinct from the unions and yet also subject to abuse. “Trusts” that are wholly owned, governed, and financed by a single union are considered subsidiaries under the LMRDA and subject to a different reporting obligation that is already part of the Form LM-2.

As to the requirement that the trust's governing board be composed of an equal number of union and employer representatives, the Department does not consider this a sufficient protection against corruption either. While the Department acknowledges that this arrangement could provide a greater deterrent to corruption relative to a board composed wholly of union appointees, this arrangement does not sufficiently operate to prevent circumvention or evasion of the overall LMRDA reporting framework that provides for financial transparency and ensures funds are directed to the benefit of union members and their beneficiaries.

As Justice Louis D. Brandeis once wrote, “Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants.” [13] The recent convictions of UAW and Fiat Chrysler officials involving funds intended for a Taft-Hartley trust meant to operate a training center for UAW members demonstrates that oversight from employer representatives is not enough.

As to the audit requirement, the Department does not consider this requirement alone or even in conjunction with the other two requirements discussed by commenters to provide an adequate justification for exempting Taft-Hartley trusts from the T-1 reporting requirements. The Department does, however, recognize that an independent audit that meets certain financial auditing standards is functionally equivalent to the financial disclosures required on the Form T-1, which is why this rule allows a union to file only the basic informational portions of the Form T-1 if it attaches such an audit. The Department allows this audit exception because it ensures that the key financial information of the trust is publicly disclosed.

Moreover, many Taft-Hartley trusts file Form 5500 reports with the Employee Benefit and Security Administration (EBSA), which exempts such trusts entirely from the Form T-1.

A commenter argued that requiring, for purposes of demonstrating managerial control, that a majority of trustees be appointed by unions would effectively free all Taft-Hartley funds from Form T-1 coverage. Management control or financial dominance is required, but not both. Under today's rule, a labor organization has management control if the labor organization alone, or in combination with other labor organizations, selects or appoints the majority of the members of the trust's governing board. Further, for purposes of today's rule, a labor organization had financial dominance if the labor organization alone, or in combination with other labor organizations, contributed more than 50 percent of the trust's receipts during the annual reporting period. This commenter proposed extending the reporting requirement to include trusts in which the labor organization selects or appoints only 50 percent of the members of the governing board, in order to maximize the application of the regulation within legal limits. The Department believes that, consistent with AFL-CIO v. Chao, labor organizations exert control over a trust, either alone or with others collectively, when labor organizations represent a majority of the trust's governing body or labor organizations contribute a majority share of receipts during the reporting period.

Additionally, many commenters discussed the Department's proposal to treat funds contributed by employers pursuant to a CBA as union funds for purposes of the financial dominance test. Some commenters supported this approach and the Department's rationale that such negotiated contributions are meant to be used to the exclusive benefit of union members and might otherwise have been secured by the union as wages or benefits for union members.

The commenters opposed to this approach advanced one or more of the following five arguments: (1) Unions are never actually in possession of these funds as they are paid directly into the trusts by employers; (2) unions cannot unilaterally determine how the funds are used because their use is governed by the agreement with the employer; (3) employer contributions are not legally considered the union's money; (4) the proposed approach could set a precedent for treating employer contributions as union money in other circumstances; and (5) the proposed approach could cause confusion about the union's relationship to the employer-contributed funds.

Initially, the Department notes that commenters did not challenge the Department's authority to apply Form T-1 reporting requirements to Taft-Hartley trusts, because that question was resolved in the affirmative by the court in AFL-CIO, 409 F.3d at 387. LMRDA section 208 grants the Secretary authority, under the Title II reporting and disclosure requirements, to issue “other reasonable rules and regulations (including rules prescribing reports concerning trusts in which a labor organization is interested) as he may find necessary to prevent the circumvention or evasion of such reporting requirements.” Employer payments to a trust are negotiated by a union. The union can choose to negotiate for numerous and varied items of value, and thus may choose to negotiate for employer concessions that do not benefit the trust. This means that the trust's continued existence depends on the union's decisions at the bargaining table. The influence that this potentially gives the union over the trust could be used to manipulate the trust's spending decisions. If so, the union has circumvented the reporting requirements by effectively making disbursements not disclosed on its Section 201 reporting form.

Further, Section 208 does not limit the “circumvention or evasion” of the reporting requirements to merely the Section 201 union disclosure requirements. Rather, such “circumvention or evasion” could also involve the Section 203 employer reporting requirements, as well as the related Section 202 union officer and employee conflict-of-interest disclosure requirements. As such, the reporting by unions of Taft-Hartley trusts could reveal whether the employer diverted, unlawfully, funds intended for the trust to a union official. For example, the public will see the amount of receipts of the trust, which could reveal whether it received all intended funds. As a further example, the public will know the entities with which such trusts deal, thereby providing a necessary safeguard against the potential circumvention or evasion by third-party employers (e.g., service providers and vendors to trusts and unions) of the Form LM-10 reporting requirements.

Next, the Department's approach to employer contributions does not state or imply that such funds were at any point held by a union. The Department considers it sufficient, in light of the limited purpose for which employer contributions are treated as union funds, that the union secured those funds for the benefit of its members and their beneficiaries as part of a negotiated CBA.

Further, the Department's concern in every facet of LMRDA financial reporting is the misuse and misappropriation of union finances. The fact that a written agreement limits the legitimate use of certain funds does not in itself prevent their misuse. That a union and its agents are not authorized to use funds for purposes other than those contemplated in the CBA is not an adequate safeguard against financial abuse. This position is supported by the reality of the misuse of employer-contributed funds by the various apprenticeship and training plans mentioned above in Part III, Section B (Policy Justifications), as well as the UAW officials tasked with overseeing a training center for UAW members.

Moreover, as a response to both the third and fourth arguments offered by commenters, the Department notes that the treatment of employer contributions as union funds is expressly limited within the rule itself to the financial dominance test. The Department is not claiming that such funds are or should be considered union funds for any other purpose. Furthermore, the Department takes this approach in this specific case only in the interest of ensuring that there is financial disclosure, as a means to prevent circumvention or evasion of the LMRDA reporting that is necessary for union financial integrity, for all funds that a union secures, by any means, for the benefit of its members and their beneficiaries. As an illustration of why employer funding pursuant to a CBA should not remain as a means to evade LMRDA reporting, consider the following example. Consider a trust that is 96 percent funded from union payments, 48 percent of which is funded by three different employers' payments made pursuant to a CBA negotiated by the same union (48 percent, or 16 percent per employer contribution). The remaining 4 percent is funded by some other, non-union entity. It is apparent that the union has a level of direct and indirect control over the trust that far exceeds any other entity that contributes to the trust and the trust would, appropriately, file under this rule. Yet, were employer contributions made pursuant to a CBA not considered by the Department, the public may not otherwise receive necessary disclosure.

As to the fifth assertion regarding potential confusion about the union's relationship to the employer-contributed funds, the Department notes that union members and the public should still be able to discern the nature of the employer-contributed funds, even if they are treated as union funds, for purposes of determining the Form T-1 reporting obligation. The rule itself and the Form T-1 instructions are clear that these funds come from the employer subject to a CBA and are treated as union funds solely for purposes of the reporting obligation. A union is also free to indicate that its trust's funds come from employer contributions in the additional information section on the Form T-1 in order to further dispel confusion. Those members of the public and of unions who take the time to review Form T-1 reports are likely familiar with Taft-Hartley trusts and the concept of employer contributions under a CBA.

D. Issues Concerning Multi-Union Trusts

In the NPRM, the Department proposed, in order to reduce the reporting burden, that parent unions may file the Form T-1 on behalf of their subordinate unions that also share an interest in a trust that triggers Form T-1 reporting. The Department sought comment on other possible methods to reduce burden in multi-union trust situations.

In regards to multi-union trusts in which managerial control or financial dominance by each participating labor organization would require a Form T-1 from each, one commenter expressed support for an approach to resolving the duplication of reports. Particularly, the commenter supported an approach allowing a single labor organization to voluntarily assume responsibility for filing the Form T-1 on behalf of all labor organizations associated with that trust. The Department agrees with this approach and it will allow a single union to file both on its behalf and on the behalf of the other unions involved. The union submitting must identify, in the Form T-1 Additional Information section, the name of each union that would otherwise be required to file a Form T-1 report for the multi-union trust. Additionally, on their Form LM-2 reports, the other unions must identify the union that filed the Form T-1 on their behalf.[14] The Department reiterates, however, that in the event the unions cannot agree on who should assume sole responsibility, each involved labor organizations will be obligated to file a Form T-1 for the reporting period.

In situations in which a single union voluntarily assumes responsibility, it may subsequently receive partial compensation from the other participating unions for doing so, pursuant to a pre-arranged agreement. Such options for consolidated filing should reduce burden, and mitigate the need for a de minimis exemption for relatively small contributors to a trust. Furthermore, the Department declines a de minimis exemption because such an exemption could allow for arrangements in which multiple unions join into a trust in such small proportions that, although they trigger the Form T-1 receipts branch of the dominance test, they each qualify for the de minimis exemption. In such a case, there would be no financial reporting despite the fact that unions exert control over the trust. Such a loophole could be exploited.

One commenter asserted that the Department is in logical error by conceiving that multiple unions, including some with minority stakes, could work in concert to circumvent reporting requirements and embezzle funds, yet provides no reason as to how this type of arrangement is “vastly out of step with reality.” One commenter also suggested that such working in concert would be effective only if the participating unions had the same affiliation. Reflecting on the ability of union officials to misdirect trust funds in all of the cases behind the convictions listed in Part III, Section B, the Department does not doubt that officials from different unions could work in concert to embezzle funds and evade reporting. Multiple unions can exercise joint control of a trust to use it as a vehicle for corruption that circumvents or evades reporting.

Finally, having received no support for such an approach, the Department declines to adopt the idea of requiring the labor organization with the largest stake in the covered trust to bear the sole responsibility of filing a Form T-1. The complexity of determining who has the largest “stake” would add additional unnecessary costs and complications; it is unclear whether the union with the largest percentage of managerial control or the largest percentage of financial contribution should be considered the stakeholder best suited to filing. Especially in situations where the difference is negligible between the size of the contributions of two unions, the rationale of obligating the largest contributor seems far less compelling.

Last, in regards to unnecessary costs to the trusts in having to provide information to multiple labor organizations instead of a single labor organization in these multi-union trust situations, the Department maintains that such additional costs are negligible. Although one commenter disagreed with the Department's reasoning, the commenter provided no evidence supporting its position. No additional information would need to be acquired in providing the information to one labor organization or multiple. The trust would forward the same files to each union. And, ultimately, the costs, including any hypothetical additional costs in providing electronic files to multiple unions instead of one, would be compensated by the unions at net zero cost to the trust.

E. ERISA Exemption

In the NPRM, the Department proposed to exempt from the Form T-1 all employee benefit trusts that are subject to Title I of ERISA and that file the Form 5500 Annual Return/Report of Employee Benefit Plan or, if applicable, the Form 5500-SF (Annual Return/Report of Small Employee Benefit Plan) (together Form 5500) with EBSA. The exemption applies even if an ERISA-covered plan was not otherwise required to submit an ERISA annual report. Effectively, this means that the exemption applies when a union has a plan covered by ERISA, and is therefore eligible under ERISA to file and files the full annual return/report of employee benefit plan or the Form 5500-SF for eligible small plans, as appropriate. A union would be exempt from filing a Form T-1 if it files an annual report under ERISA unless it files a Form 5500-SF without meeting the eligibility requirements for filing the simplified report, such as being a multi-employer plan, not having the correct plan membership size, or not being invested in “eligible plan assets.” [15] For example, a multi-employer apprenticeship and training plan must file the full Form 5500, not the SF, in order for the union to qualify for this Form T-1 exemption. The Department received numerous comments in response to this proposal, and, while the Department retains the ERISA exemption in the final rule, the Department has modified the regulatory language and Form T-1 instructions to make clear its scope.

The commenters opposed to this exemption argued that the Form 5500 does not offer comparable disclosure. They also stated that ERISA and the LMRDA serve different purposes.

Those who supported the exemption argued that the Form 5500 exemption should be retained. ERISA exemptions have always been a feature of the Form T-1 filing requirements, and the reasoning has not changed. The Form 5500 offers disclosure and accountability for both employee benefit pension plans and employee benefit welfare plans operated with a trust comparable to what the Form T-1 offers. The commenters argued that, were no Form 5500 exemption granted, the resulting redundancy created by the overlapping reports would be an unjustifiable burden on labor organizations with no justifiable gain in disclosure for members. Moreover, some commenters maintained that the Form 5500 provides even greater transparency than the Form T-1, because the itemization threshold for reporting certain payments to service providers is only $5,000 on Form 5500 as opposed to $10,000 on the Form T-1. The Form 5500 also requires reporting of certain types of indirect compensation, not just direct compensation, paid to or received by a service provider. Finally, Form 5500 filers with plans funded by trusts generally have to file an audit report based on an audit conducted by an independent, qualified public accountant.

A commenter took the position that the Form 5500 does not offer sufficient disclosure and that ERISA works to blunt inquiry for members. Another commenter claimed that there is “no rationale basis [sic]” for the Department to believe the Form 5500 will adequately inform members for the purposes of maintaining democratic control of their union or to ensure a proper accounting of union funds. The Department disagrees with these statements. First, the Form 5500 has for decades provided important financial disclosure regarding the entities that file it. Second, the Form 5500 is available to not only participants, beneficiaries, and fiduciaries, but to union members and to the public. Members interested in the operations of the employee benefit trusts to which their union contributes can continue to utilize it for the effective monitoring of those filing entities. While the first commenter also suggested that the Form 5500 is inappropriate because the LMRDA and ERISA serve different purposes, this does not have any bearing on the quality of Form 5500 disclosure or the salience of those disclosures for these purposes. In any event, in the Department's view, the transparency provided by the Form 5500 can serve the purposes of both statutes.

Another commenter argued that the Form 5500 exemption should not be included because the additional burden of preparing the Form T-1 would be minimal. The trust would already have garnered much of the information needed when it was preparing the Form 5500. While it is true that similar information from the same sources would reduce the burden of a second form, even a reduced unnecessary burden is still an unnecessary burden. The exemption avoids any unnecessary burden in relation to the Form T-1.

The Department agrees with the reasoning offered by one union commenter as to why the Form 5500 exemption has long been a feature of Form T-1 initiatives and should be maintained. The exemption reduces the redundancy of information already publicly available, and eliminates burden hours that would be otherwise borne by the union. The exemption is, as another commenter explained, well-founded because Form 5500 reporting already ensures transparency and accountability to members whose trusts file. Lastly, as one accounting firm commenter reasoned, the Form 5500 is arguably superior in certain respects to the Form T-1, primarily the lower threshold for identifying recipients of disbursements which is set at $5,000 as opposed to $10,000.[16]

The ERISA exemption would require a union to take the step of determining whether or not a given trust covered by this rule in which it has an interest files the Form 5500 with EBSA.[17] On this point, one commenter argued that unions would have no more difficulty in finding out whether their trust files a Form 5500 than determining and acquiring all of the necessary information from the trust for the completion of the Form T-1. Again, the Form 5500 is publicly available, including via a simple search on the Department's Form 5500 online Search Tool.[18] Furthermore, when contacted by the union, the trust would know if it files the Form 5500 and could indicate the fact to the union. Thus, the Department remains convinced that the exemption for trusts that file the Form 5500 with EBSA should remain.

In a closely related issue, some commenters expressed concern that the trust's provision of information to the union for purposes of completing the Form T-1 raises ERISA fiduciary duty and prohibited transaction issues. In this regard, ERISA requires that plan assets be used only for the provision of plan benefits or for defraying the reasonable expenses of administering a plan. See 29 U.S.C. 1103(c)(2) and 1104(a)(1)(A). Moreover, ERISA prohibits, subject to exemptions, a plan fiduciary from using plan assets for the benefit of a party in interest, a term that includes a union whose members are covered by the plan. See 29 U.S.C. 1002(14)(D), 1106(a)(1)(D). Additionally, other commenters argued that when a trust enters an agreement with a union to receive reimbursement for costs incurred in providing Form T-1 data to a union, union trustees will have to recuse themselves in order to avoid violating ERISA's self-dealing restrictions in agreeing to the amount and terms of the reimbursement. These same issues were raised by commenters in connection with the 2008 final Form T-1 rule. Specifically, in the preamble to the 2008 rule, the Department noted that “[i]n addition to the ERISA section 404 concerns, a number of comments also pointed out that ERISA section 406(b), 29 U.S.C. 1106(b), prohibits a fiduciary and a labor organization trustee who is a labor organization official from acting in an ERISA plan transaction, including providing services, involving his or her labor organization.”