AGENCY:

Securities and Exchange Commission.

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

The Securities and Exchange Commission (the “Commission” or the “SEC”) is adopting amendments under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 (the “Advisers Act” or the “Act”) to update rules that govern investment adviser marketing. The amendments will create a merged rule that will replace both the current advertising and cash solicitation rules. These amendments reflect market developments and regulatory changes since the advertising rule's adoption in 1961 and the cash solicitation rule's adoption in 1979. The Commission is also adopting amendments to Form ADV to provide the Commission with additional information about advisers' marketing practices. Finally, the Commission is adopting amendments to the books and records rule under the Advisers Act.

DATES:

Effective date: This rule is effective May 4, 2021.

Compliance dates: The applicable compliance dates are discussed in section II.K.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Juliet Han, Emily Rowland, Aaron Russ, or Christine Schleppegrell, Senior Counsels; Thoreau Bartmann or Melissa Roverts Harke, Senior Special Counsels; or Melissa Gainor, Assistant Director, at (202) 551-6787 or IM-Rules@sec.gov, Investment Adviser Regulation Office, Division of Investment Management, Securities and Exchange Commission, 100 F Street NE, Washington, DC 20549-8549.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

The Commission is adopting amendments to 17 CFR 275.206(4)-1 (rule 206(4)-1) and 17 CFR 275.204-2 (rule 204-2) under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 [15 U.S.C. 80b-1 et seq.],[1] and amendments to 17 CFR 279.1 (Form ADV) under the Advisers Act. The Commission is rescinding 17 CFR 275.206(4)-3 (rule 206(4)-3) under the Advisers Act.

Table of Contents

I. Introduction

Advertising and Solicitation Rules and Proposed Amendments

Merged Marketing Rule

II. Discussion

A. Scope of the Rule: Definition of “Advertisement”

1. Overview

2. Definition of Advertisement: Communications Other Than Compensated Testimonials and Endorsements

3. Definition of Advertisement: Compensated Testimonials and Endorsements, Including Solicitations

4. Investors in Private Funds

B. General Prohibitions

1. Untrue Statements and Omissions

2. Unsubstantiated Material Statements of Fact

3. Untrue or Misleading Implications or Inferences

4. Failure To Provide Fair and Balanced Treatment of Material Risks or Material Limitations

5. Anti-Cherry Picking Provisions: References to Specific Investment Advice and Presentation of Performance Results

6. Otherwise Materially Misleading

C. Conditions Applicable to Testimonials and Endorsements, Including Solicitations

1. Overview

2. Required Disclosures

3. Adviser Oversight and Compliance

4. Disqualification for Persons Who Have Engaged in Misconduct

5. Exemptions

D. Third-Party Ratings

E. Performance Advertising

1. Net Performance Requirement; Elimination of Proposed Schedule of Fees Requirement

2. Prescribed Time Periods

3. Statements About Commission Approval

4. Related Performance

5. Extracted Performance

6. Hypothetical Performance

F. Portability of Performance, Testimonials, Endorsements, Third-Party Ratings, and Specific Investment Advice

G. Review and Approval of Advertisements

H. Amendments to Form ADV

I. Recordkeeping

J. Existing Staff No-Action Letters

K. Transition Period and Compliance Date

L. Other Matters

III. Economic Analysis

A. Introduction

B. Broad Economic Considerations

C. Baseline

1. Market for Investment Advisers for the Advertising Rule

2. Market for Solicitation Activity

3. RIA Clients

D. Costs and Benefits of the Final Rule and Form Amendments

1. Quantitative Estimates of Costs and Benefits

2. Definition of Advertisement

3. General Prohibitions

4. Conditions Applicable to Testimonials and Endorsements, Including Solicitations

5. Third-Party Ratings

6. Performance Advertising

7. Amendments to Form ADV

8. Recordkeeping

E. Efficiency, Competition, Capital Formation

1. Efficiency

2. Competition

3. Capital Formation

F. Reasonable Alternatives

1. Reduce or Eliminate Specific Limitations on Investment Adviser Advertisements

2. Bifurcate Some Requirements

3. Hypothetical Performance Alternatives

4. Alternatives to the Combined Marketing Rule

5. Alternatives to Disqualification Provisions

IV. Paperwork Reduction Act Analysis

A. Introduction

B. Rule 206(4)-1

1. General Prohibitions

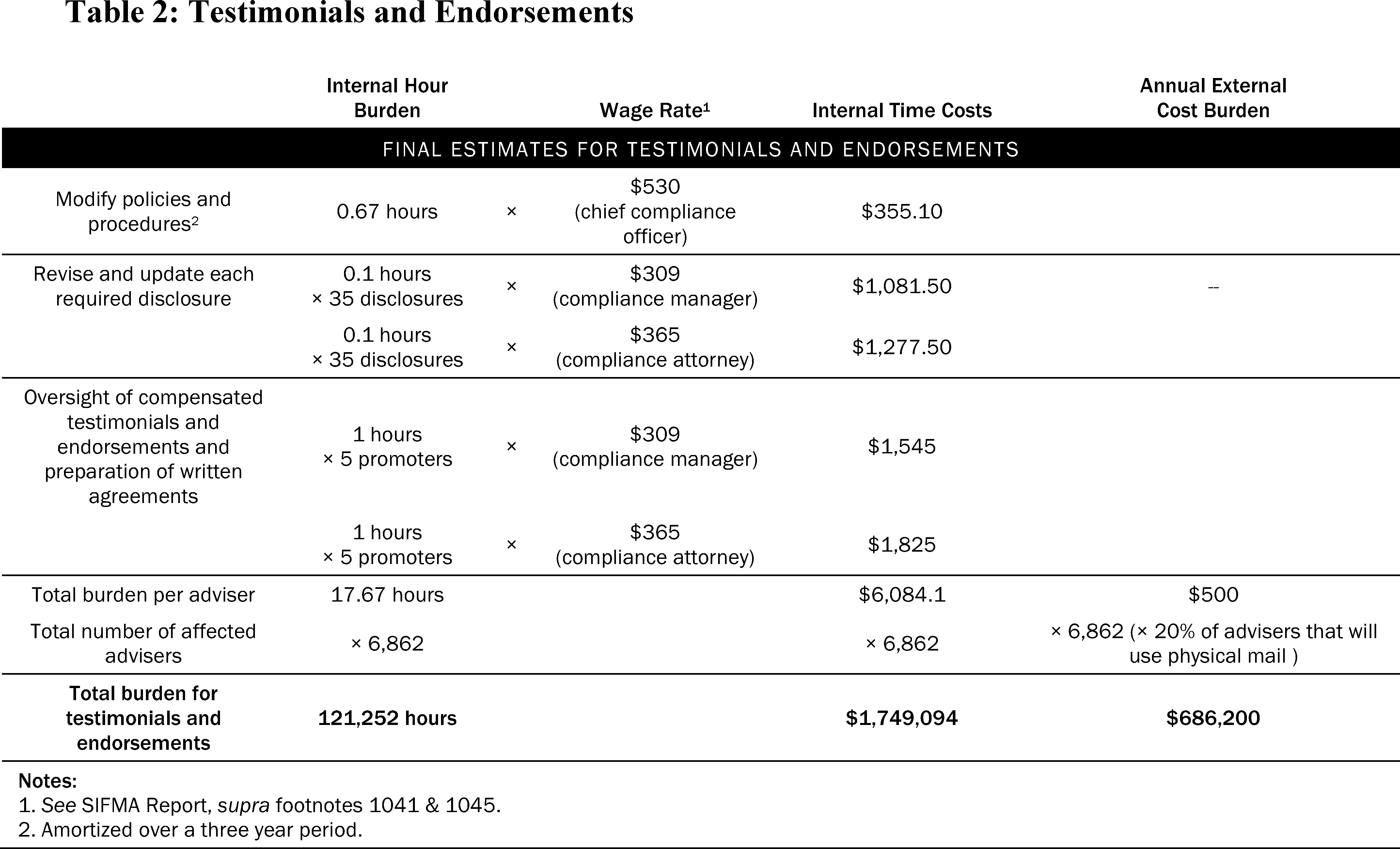

2. Testimonials and Endorsements in Advertisements

3. Third-Party Ratings in Advertisements

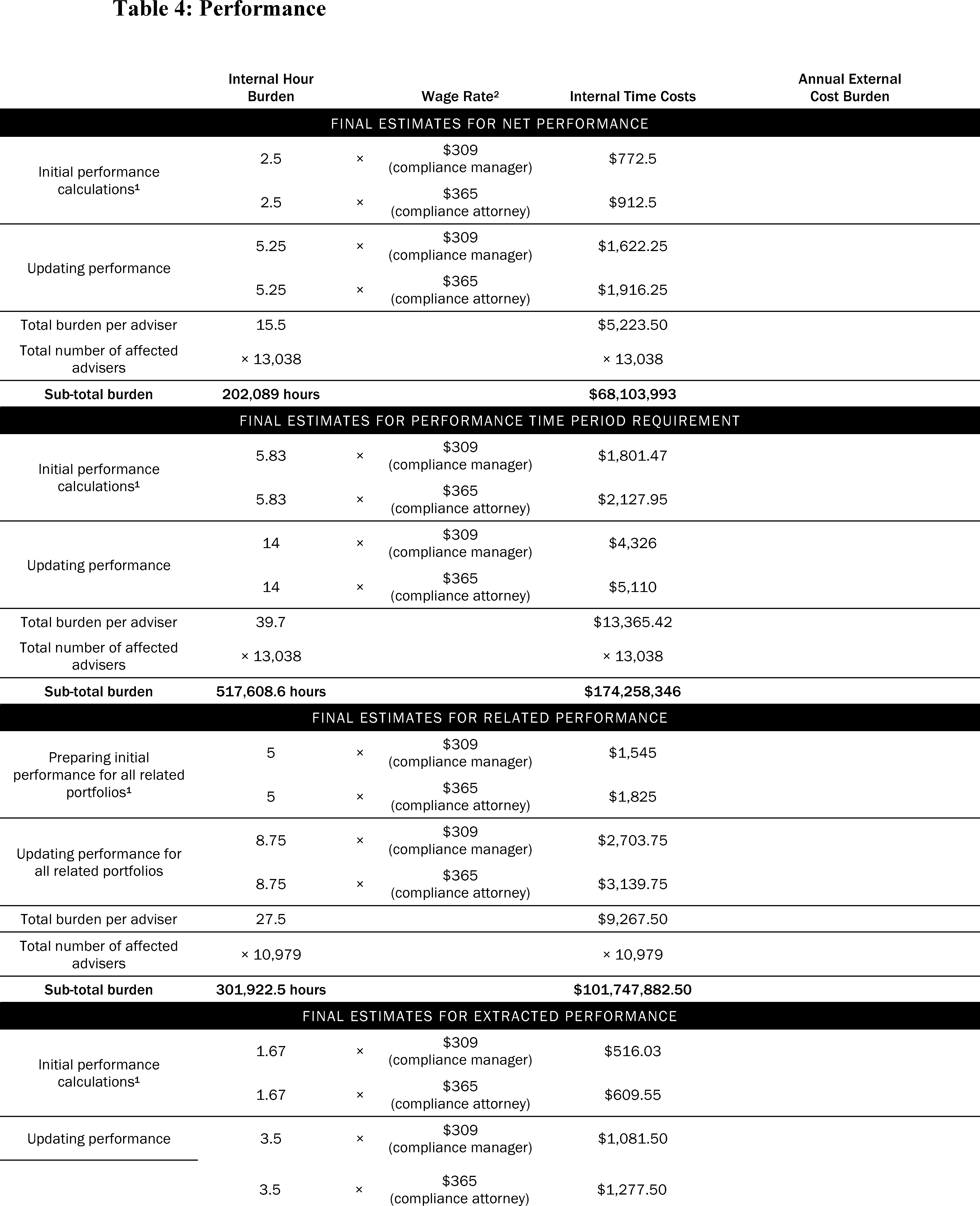

4. Performance Advertising

5. Total Hour Burden Associated With Rule 206(4)-1

C. Rule 206(4)-3

D. Rule 204-2

E. Form ADV

V. Final Regulatory Flexibility Analysis

A. Reason for and Objectives of the Final Amendments

1. Final Rule 206(4)-1

2. Final Rule 204-2

3. Final Amendments to Form ADV

B. Significant Issues Raised by Public Comments

C. Legal Basis

D. Small Entities Subject to the Rule and Rule Amendments

1. Small Entities Subject to Amendments to Marketing Rule

2. Small Entities Subject to Amendments to the Books and Records Rule 204-2

3. Small Entities Subject to Amendments to Form ADV

E. Projected Reporting, Recordkeeping and Other Compliance Requirements

1. Final Rule 206(4)-1

2. Final Amendments to Rule 204-2

3. Final Amendments to Form ADV

F. Duplicative, Overlapping, or Conflicting Federal Rules

1. Final Rule 206(4)-1

2. Final Amendments to Form ADV

G. Significant Alternatives

1. Final Rule 206(4)-1

Statutory Authority

Appendix A: Changes to Form ADV

Appendix B: Form ADV Glossary of Terms

I. Introduction

We are adopting an amended rule, rule 206(4)-1, under the Advisers Act, which addresses advisers marketing their services to clients and investors (the “marketing rule”). The marketing rule amends existing rule 206(4)-1 (the “advertising rule”), which we adopted in 1961 to target advertising practices that the Commission believed were likely to be misleading.[2] The rule also replaces rule 206(4)-3 (the “solicitation rule”), which we adopted in 1979 to help ensure clients are aware that paid solicitors who refer them to advisers have a conflict of interest.[3] We have not substantively updated either rule since adoption.[4] In the decades since the adoption of both rules, however, advertising and referral practices have evolved. Simultaneously, the technology used for communications has advanced, the expectations of investors shopping for advisory services have changed, and the profiles of the investment advisory industry have diversified.

Our marketing rule recognizes these changes and our experience administering the advertising and solicitation rules. Accordingly, the rule contains principles-based provisions designed to accommodate the continual evolution and interplay of technology and advice. The rule also contains tailored restrictions and requirements for certain types of advertisements, such as performance advertising, testimonials and endorsements, and third-party ratings. Compensated testimonials and endorsements, which include traditional referral and solicitation activity, will be subject to disqualification provisions. We believe the final marketing rule will allow advisers to provide existing and prospective investors with useful information as they choose among investment advisers and advisory services, subject to conditions that are reasonably designed to prevent fraud.

Finally, we are adopting related amendments to Form ADV that are designed to provide the Commission with additional information about advisers' marketing practices, and related amendments to the Advisers Act books and records rule, rule 204-2.

Advertising and Solicitation Rules and Proposed Amendments

Advertisements can provide existing and prospective investors with useful information as they contemplate whether to utilize and pay for investment advisory services, whether to approach particular investment advisers, and how to choose among their available options. At the same time, advertisements present risks of misleading investors because an investment adviser's interest in attracting investors may conflict with the investors' interests, and the adviser is in control of the design, content, format, media, timing, and placement of its advertisements. As a consequence, advertisements may mislead existing and prospective investors about the advisory services they will receive, including indirectly through the services provided to private funds.[5] The advertising rule was designed to address the potential harm to investors from misleading advertisements.

Advisers also attract investors by compensating individuals or firms to solicit new investors. Some investment advisers directly employ individuals to solicit new investors on their behalf, and some investment advisers arrange for related entities or third parties, such as broker-dealers, to solicit new investors. The person or entity compensated has a financial incentive to recommend the adviser to the investor.[6] Without appropriate disclosure, this compensation creates a risk that an investor would mistakenly view the recommendation as being an unbiased opinion about the adviser's ability to manage the investor's assets and would rely on that recommendation more than the investor would if the investor knew of the incentive. The solicitation rule was designed to help expose to clients the conflicts of interest posed by cash compensation.

The concerns that motivated the Commission to adopt the advertising and solicitation rules still exist today, but investment adviser marketing has evolved with advances in technology. In the decades since the adoption of both the advertising and solicitation rules, the use of the internet, mobile applications, and social media has become an integral part of business communications. Consumers today often rely on these forms of communication to obtain information, including reviews and referrals, when considering buying goods and services. Advisers and third parties also rely on these same types of outlets to attract and refer potential customers.

The nature and profiles of the investment advisory industry and investors seeking those advisory services have also changed since the Commission adopted the advertising and solicitation rules. Some investors today rely on digital investment advisory programs, sometimes referred to as “robo-advisers,” for investment advice, which is provided exclusively through electronic platforms using algorithmic-based programs. In addition, passage of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (“Dodd-Frank Act”) required many investment advisers to private funds that were previously exempt from registration to register with the Commission and become subject to additional provisions of the Advisers Act and the rules thereunder. Private funds and their advisers often hire promoters to obtain investors in the funds. Referral practices also have expanded to include, for example, various types of compensation, including non-cash compensation, in referral arrangements.

In light of these developments, we proposed amendments to the advertising rule to: (i) Modify the definition of “advertisement” to be more “evergreen” in light of ever-changing technology; (ii) replace four per se prohibitions with general prohibitions of certain advertising practices applicable to all advertisements; (iii) provide certain restrictions and conditions on testimonials, endorsements, and third-party ratings; and (iv) include tailored requirements for the presentation of performance results, based on an advertisement's intended audience.7The proposed rule also would have required internal review and approval of most advertisements. Finally, we proposed amendments requiring each adviser to report additional information regarding its advertising practices in its Form ADV.

Additionally, we proposed amendments to the solicitation rule to: (i) Expand the rule to cover solicitation arrangements involving all forms of compensation, rather than only cash compensation; (ii) expand the rule to apply to the solicitation of current and prospective investors in any private fund, rather than only to “clients” (including prospective clients) of the investment adviser; (iii) eliminate requirements duplicative of other rules; (iv) include exceptions for de minimis payments and certain non-profit programs; and (v) expand the types of disciplinary events that would trigger the rule's disqualification provisions.

We received more than 90 comment letters on the proposal.[8] The Commission also received feedback flyers from individual investors on investment adviser marketing and from smaller advisers on the proposal's effects on small entities.[9] Commenters generally supported modernizing these rules and agreed with our general approach. Many commenters, however, expressed concern that several aspects of the proposed amendments to the advertising rule would increase an investment adviser's compliance burden.[10] For example, some commenters suggested removing the proposed internal pre-use review and approval requirement and narrowing the proposed definition of “advertisement.” [11] Others requested that we provide additional guidance on various topics, such as how the general prohibitions will apply in certain scenarios.[12] Commenters also expressed concern that the proposed amendments to the solicitation rule would significantly expand several aspects of the existing rule. For example, some commenters argued that the proposed definition of “solicitor” was too broad and suggested alternatives or limitations.[13] Others disagreed with the proposed expansion of the rule to include non-cash compensation and solicitations of private fund investors.[14] Commenters also recommended modifications to the disqualification provisions, such as aligning them with disqualification provisions in our other rules and limiting the scope of affiliate disqualification.[15]

Commenters generally supported our approach to permit testimonials and endorsements; [16] however, they highlighted the difficulty in assessing when compensated testimonials and endorsements under the proposed advertising rule would also trigger the application of the proposed solicitation rule.[17] Commenters argued that applying both rules to the same conduct is duplicative and burdensome.[18] Some commenters suggested that we regulate endorsements and testimonials only under the advertising rule,[19] whereas others suggested various ways to limit the conduct that would be subject to both rules.[20]

Merged Marketing Rule

After considering comments, we are adopting a rule with several modifications.[21] We believe it is appropriate to regulate investment adviser advertising and solicitation activity through a single rule: The marketing rule. This approach is designed to balance the Commission's goals of protecting investors from misleading advertisements and solicitations, while accommodating current marketing practices and their continued evolution.

- The final marketing rule will include an expanded definition of “advertisement,” relative to the current advertising rule, that will encompass an investment adviser's marketing activity for investment advisory services with regard to securities. We have determined not to expand the definition of advertisement to include communications addressed to one person as proposed, and instead will retain the current rule's exclusion of one-on-one communications from the definition, except with regard to compensated testimonials and endorsements and certain communications that include hypothetical performance information.[22] In addition, the definition will not include communications designed to retain existing investors. The final definition also will include exceptions for extemporaneous, live, oral communications; and information contained in a statutory or regulatory notice, filing, or other required communication.

- Largely as proposed, the final rule will apply to certain communications sent to clients and private fund investors, but will not apply to advertisements about registered investment companies or business development companies.

- A set of seven principles-based general prohibitions will apply to all advertisements. These are drawn from historic anti-fraud principles under the Federal securities laws and are tailored specifically to the type of communications that are within the scope of the rule.

- The final rule will permit an adviser's advertisement to include testimonials and endorsements, subject generally to the following conditions: Required disclosures; adviser oversight and compliance, including a written agreement for certain promoters; and, in some cases, disqualification provisions. We are adopting partial exemptions for de minimis compensation, affiliated personnel, registered broker-dealers, and certain persons to the extent they are covered by rule 506(d) of Regulation D under the Securities Act with respect to a securities offering.

- An adviser's advertisement may include a third-party rating, if the adviser forms a reasonable belief that the third-party rating clearly and prominently discloses certain information.

- The final rule will apply to performance advertising and will require presentation of net performance information whenever gross performance is presented, and performance data over specific periods. In addition, the final rule will impose requirements on advisers that display related performance, extracted performance, hypothetical performance, and—in a change from the proposal—predecessor performance. We are not adopting, however, the proposed separate requirements for performance advertising for retail and non-retail investors.

- We are amending the recordkeeping rule and Form ADV to reflect the final rule and enhance the data available to support our staff's enforcement and examination functions.

- In a change from the proposal, the final rule will not require investment advisers to review and approve their advertisements prior to dissemination.

- Finally, certain staff no-action letters will be withdrawn in connection with the final rule as those positions are either incorporated into the final rule or will no longer apply.

II. Discussion

A. Scope of the Rule: Definition of “Advertisement”

1. Overview

Under the final marketing rule, the definition of an advertisement includes two prongs.[23] The first prong includes any direct or indirect communication an investment adviser makes that: (i) Offers the investment adviser's investment advisory services with regard to securities to prospective clients or investors in a private fund advised by the investment adviser (“private fund investors”), or (ii) offers new investment advisory services with regard to securities to current clients or private fund investors.[24] This prong will capture traditional advertising, and will not include one-on-one communications, unless the communication includes hypothetical performance information that is not provided: (i) In response to an unsolicited investor request or (ii) to a private fund investor. It also excludes (i) extemporaneous, live, oral communications; and (ii) information contained in a statutory or regulatory notice, filing, or other required communication, provided that such information is reasonably designed to satisfy the requirements of such notice, filing, or other required communication.[25]

The new second prong will cover compensated testimonials and endorsements, which will include a similar scope of activity as traditional solicitations under the current solicitation rule.[26] This prong will include oral communications and one-on-one communications to capture traditional one-on-one solicitation activity, in addition to solicitations for non-cash compensation. It will exclude certain information contained in a statutory or regulatory notice, filing, or other required communication.[27]

2. Definition of Advertisement: Communications Other Than Compensated Testimonials and Endorsements

Proposed rule 206(4)-1(e)(1) would have defined an advertisement as any communication, disseminated by any means, by or on behalf of an investment adviser, that offers or promotes the investment adviser's investment advisory services or that seeks to obtain or retain one or more investment advisory clients or private fund investors, subject to certain enumerated exclusions. Although some commenters supported the proposed definition,[28] most commenters stated that it was overly broad.[29] Some commenters stated that the proposed definition would chill adviser communications to existing investors, increase compliance burdens for advisers, and complicate communications with various third parties.[30]

After considering comments, we are making several modifications to hone the scope of the rule to the communications that have a greater risk of misleading investors, ease compliance burdens that commenters suggested would result from the proposed rule's scope, and facilitate communications with existing investors.

a. Specific Provisions

In a textual (but not substantive) change from the proposal, the final rule will not include the phrase “disseminated by any means” and instead will reference any direct or indirect communication the adviser makes. We believe these two formulations carry the same meaning, but understand from commenters that the phrase “direct or indirect” is more familiar to advisers. This reference to direct or indirect communications will replace the current advertising rule's requirement that an advertisement be a “written” communication or a notice or other announcement “by radio or television.” We are deleting references in the current advertising rule to specific types of communications to ensure that the final rule reflects modern communication methods, rather than the methods that were most common when the Commission adopted the current rule (e.g., newspapers, television, and radio). Commenters generally did not oppose omitting the current rule's references to specific methods of communication and supported such modernization of the current rule.[31]

This revision will expand the scope of the current rule to encompass all offers of an investment adviser's investment advisory services with regard to securities regardless of how they are disseminated, with the limited exceptions discussed below. An adviser may disseminate such communications through emails, text messages, instant messages, electronic presentations, videos, films, podcasts, digital audio or video files, blogs, billboards, and all manner of social media, as well as by paper, including in newspapers, magazines, and the mail. We recognize that electronic media (including social media and other internet communications) and mobile communications play a significant role in current advertising practices. We also believe this revision will help the definition remain evergreen in the face of evolving technology and methods of communication.

i. Any Direct or Indirect Communication an Investment Adviser Makes

The first prong of the final marketing rule's definition of “advertisement” includes an adviser's direct or indirect communications. In addition to communicating directly with prospective investors, we understand that investment advisers often provide intermediaries, such as consultants, other advisers (e.g., in a fund-of-funds or feeder funds structure), and promoters, with advertisements for dissemination. Those advertisements are indirect communications because they are statements provided by the adviser for dissemination by a third party. This aspect of the definition also will capture certain communications distributed by an adviser that incorporate statements or other content prepared by a third party.[32]

The final rule text reflects a change from the proposal, which would have applied to any communications “by or on behalf of” an adviser.[33] Commenters generally suggested that we remove the “on behalf of” clause from the definition, citing concerns that advisers would not be able to collaborate with third parties to prepare and disseminate advertising materials and that it would stifle communications between advisers and certain third parties.[34] Certain commenters requested safe harbors for communications with the press and removal of profane or illegal materials.[35] Commenters also requested clarification on how the rule would apply to funds-of-funds, model providers, solicitors, and employee use of social media.[36]

We believe communications that investment advisers use to offer their advisory services have an equal potential to mislead—and should be subject to the rule—regardless of whether the adviser communicates directly or indirectly through a third party, such as a consultant, intermediary, or related person.[37] Likewise, an adviser should not be able to avoid application of the rule when it incorporates third-party content into its communications.[38] To address commenters' concerns about the clarity of the standard, however, we replaced “on behalf of” with “directly or indirectly.” Our view is that these phrases largely have the same meaning, but that “directly or indirectly” is more commonly used, broadly understood, and consistent with the language in the current rule. In addition, we believe that the phrase “direct or indirect communication an investment adviser makes” better focuses on an adviser's participation in making a particular communication subject to the rule.

Whether a particular communication is a communication made by the adviser is a facts and circumstances determination. Where the adviser has participated in the creation or dissemination of an advertisement, or where an adviser has authorized a communication, the communication would be a communication of the adviser. For example, if an adviser provides marketing material to a third party for dissemination to potential investors, the communication is a communication made by the adviser. In addition, we would generally view any advertisement about the adviser that is distributed and/or prepared by a related person as an indirect communication by the adviser, and thus subject to the final rule.[39] Although the final marketing rule will not require an adviser to oversee all activities of a third party, the adviser is responsible for ensuring that its advertisements comply with the rule, regardless of who creates or disseminates them.

An adviser might collaborate with a third party to prepare marketing materials in other circumstances that would not constitute dissemination by an adviser. If an adviser provides comments on a marketing piece, but a third party does not accept the adviser's comments or the third party makes unauthorized modifications, the adviser will not be responsible for the third party's subsequent modifications that were made independently of the adviser and that the adviser did not approve.[40] This analysis would be based on the facts and circumstances. Formal authorization of dissemination, or lack thereof, by the adviser is not dispositive, although it would be considered part of the analysis.

Commenters sought clarification on how the definition of “advertisement” would apply in the fund-of-funds and master-feeder contexts.[41] If an adviser to an underlying fund provides marketing materials to the adviser of a fund-of-funds (or a feeder fund) and the adviser to the fund-of-funds (or a feeder fund) provides those materials to investors, the underlying fund adviser would be responsible for the material it prepared or authorized for distribution.[42] The underlying fund adviser would not be responsible for modifications the adviser of the fund-of-funds made to the underlying fund adviser's original advertisement if the underlying fund adviser did not approve the adviser's edits. Similarly, a third-party model provider would not be responsible for modifications the end-user adviser made to the third-party model used in an advertisement if done without the model provider's involvement or authorization.

Adoption and Entanglement

Depending on the particular facts and circumstances, third-party information also may be attributable to an adviser under the first prong of the final rule. For example, an adviser may distribute information generated by a third party or a third party could include information about an adviser's investment advisory services in the third party's materials. In these scenarios, whether the third-party information is attributable to the adviser will require an analysis of the facts and circumstances to determine (i) whether the adviser has explicitly or implicitly endorsed or approved the information after its publication (adoption) or (ii) the extent to which the adviser has involved itself in the preparation of the information (entanglement).[43]

An adviser “adopts” third-party information when it explicitly or implicitly endorses or approves the information.[44] For example, if an adviser incorporates information it receives from a third party into its performance advertising, the adviser has adopted the third-party content, and the third-party content will be attributed to the adviser.[45] An adviser is liable for such third-party content under the marketing rule just as it would be liable for content it produced itself.[46] In addition, an adviser may have “entangled” itself in a third-party communication if the adviser involves itself in the third party's preparation of the information.[47]

Nevertheless, we would not view an adviser's edits to an existing third-party communication to result in attribution of that communication to the adviser if the adviser edits a third party's communication based on pre-established, objective criteria (i.e., editing to remove profanity, defamatory or offensive statements, threatening language, materials that contain viruses or other harmful components, spam, unlawful content, or materials that infringe on intellectual property rights, or editing to correct a factual error) that are documented in the adviser's policies and procedures and that are not designed to favor or disfavor the adviser.[48] In these circumstances, we would not view the adviser as endorsing or approving the remaining content by virtue of such limited editing.

Guidance on Social Media

Questions about whether a communication is attributable to an adviser may commonly arise in the context of an adviser's use of websites or other social media. For example, an adviser might include a hyperlink in an advertisement to an independent web page on which third-party content sits. An adviser should consider the adoption and entanglement concepts discussed above to determine whether the hyperlinked third-party content would be attributed to the adviser.[49] At the same time, an adviser's hyperlink to third-party content that the adviser knows or has reason to know contains an untrue statement of material fact or materially misleading information would also be fraudulent or deceptive under section 206 of the Act and other applicable anti-fraud provisions.

Whether content posted by third parties on an adviser's own website or social media page would be attributed to the investment adviser also depends on the facts and circumstances surrounding the adviser's involvement.[50] For example, permitting all third parties to post public commentary to the adviser's website or social media page would not, by itself, render such content attributable to the adviser, so long as the adviser does not selectively delete or alter the comments or their presentation and is not involved in the preparation of the content.[51] We believe such treatment of third-party content on the adviser's own website or social media page is appropriate even if the adviser has the ability to influence the commentary but does not exercise this authority. For example, if the social media platform allows the investment adviser to sort the third-party content in such a way that more favorable content appears more prominently, but the investment adviser does not actually do such sorting, then the ability to sort content would not, by itself, render such content attributable to the adviser. In addition, if an adviser merely permits the use of “like,” “share,” or “endorse” features on a third-party website or social media platform, we would not interpret the adviser's permission as implicating the final rule.

Conversely, if the investment adviser takes affirmative steps to involve itself in the preparation or presentation of the comments, to endorse or approve the comments, or to edit posted comments, those comments would be attributed to the adviser. This would apply to the affirmative steps an adviser takes both on its own website or social media pages, as well as on third-party websites. For example, if an adviser substantively modifies the presentation of comments posted by others by deleting or suppressing negative comments or prioritizing the display of positive comments, then we would attribute the comments to the adviser (i.e., the communication would be an indirect statement of the adviser) because the adviser would have modified third-party comments with the goal of marketing its advisory business. However, as discussed above, we would not view an adviser's merely editing profane, unlawful, or other such content according to a neutral pre-existing policy as the adviser adopting the content.

Some commenters sought assurances that the definition of advertisement would not cover an adviser's associated persons' activity on their personal social media accounts.[52] We have concerns that, under certain circumstances, it could be difficult for an investor to differentiate a communication of the associated person in his/her personal capacity from a communication the associated person made for the adviser. With respect to social media postings to associated persons' own accounts, it would be a facts and circumstances analysis relating to the adviser's supervision and compliance efforts. If the adviser adopts and implements policies and procedures reasonably designed to prevent the use of an associated person's social media accounts for marketing the adviser's advisory services, we generally would not view such communication as the adviser marketing its advisory services.[53] To achieve effective supervision and compliance, an adviser may consider also prohibiting such communications, conducting periodic training, obtaining attestations, and periodically reviewing content that is publicly available on associated persons' social media accounts.

ii. To More Than One Person

Consistent with the current rule's exclusion of one-on-one communications, the first prong of the final definition of “advertisement” generally does not include communications to one person. While our proposed rule would have treated communications directed to “one or more” persons as advertisements, commenters generally opposed this expansion.[54] In particular, commenters argued that subjecting one-on-one communications to the requirements of the proposed rule would create untenable burdens given the proposed review and approval obligation (including enhanced recordkeeping requirements).[55] Commenters also stated that it would chill adviser/investor communications.[56] According to commenters, scoping a one-on-one communication into the rule would require advisers to review each communication to determine whether it is an advertisement, which could prevent an adviser from providing timely information to investors and satisfying its fiduciary obligations.[57] We received comments that communications to existing investors are already subject to the anti-fraud provisions of the Advisers Act, and therefore communications to existing investors need not be subject to the final rule.[58]

After considering the comments, we have determined to exclude one-on-one communications from the first prong of the definition and retain the “more than one” language in the current advertising rule, unless such communications include hypothetical performance information that is not provided: (i) In response to an unsolicited investor request or (ii) to a private fund investor. We have made this change to avoid the possibility that the rule would impede typical communications between advisers and their existing and prospective investors. An adviser might have been dis-incentivized to communicate regularly with its investors if it believed it would have to analyze every communication for compliance with the proposed rule.[59]

Because we are excluding one-on-one communications from the first prong of the definition of advertisement under most circumstances, we are modifying the proposed exclusion for an adviser's responses to unsolicited requests.[60] Although commenters generally supported the exclusion and recommended expanding it,[61] we believe excluding most one-on-one communications addresses commenter concerns in a more comprehensive manner than the unsolicited request exclusion would have addressed them. The definition will exclude an adviser's responses to an unsolicited investor request for hypothetical performance information, as well as hypothetical performance information provided to a private fund investor in a one-on-one communication, as discussed below. Unless subject to this or another exclusion, the definition of advertisement will capture communications that include hypothetical performance information even in a one-on-one communication.[62]

We also recognize that advisers have one-on-one interactions with prospective investors and that prospective investors may ask questions of an adviser or ask for additional information. In adopting the current advertising rule, the Commission limited the definition of “advertisement” due to concerns that a broad definition could encompass even “face to face conversations between an investment counsel and his prospective client.” [63] The Commission stated that it would not include a “personal conversation” with a client or prospective client.[64] We believe that the same concerns that influenced the Commission's prior approach continue to exist. We also believe that the remaining provisions of the definition, as well as other provisions of the Federal securities laws, are adequate to satisfy our investor protection goals with respect to communications directed only to a single individual or entity.[65]

The one-on-one exclusion in the definition's first prong applies regardless of whether the adviser makes the communication to a natural person with an account or multiple natural persons representing a single entity or account.[66] The exclusion applies to a single adviser and a single investor. For example, if an adviser's prospective investor is an entity, the exclusion permits the adviser to provide communications to multiple natural persons employed by or owning the entity without those communications being subject to the rule. For purposes of this exclusion, we also interpret the term “person” to mean one or more investors that share the same household. For example, a communication to a married couple that shares the same household would qualify for the one-on-one exclusion.[67]

Some commenters advocated that we increase the “more than one” threshold from the current rule to communications with “more than ten” or “more than 25” persons.[68] They argued that such a change would reduce compliance costs and better align with traditional concepts of advertising.[69] We decline to make this change. The exclusion from the first prong of the definition of advertisement for one-on-one communications will allow an adviser to engage in routine investor communications and have personal conversations with prospective investors, without subjecting those communications to the final marketing rule's requirements. However, we continue to believe that the final rule should cover typical marketing communications, even if sent to a limited number of persons. Creating a higher threshold, as suggested by commenters, may incentivize advisers to limit communications to just below the threshold number of persons, and may defeat the purposes of our final rule.

While the first prong of the final rule will generally not apply to communications to one person, changes in technology since the adoption of the existing rule permit advisers to create communications that appear to be personalized to single investors and are “addressed to” only one person, but are actually widely disseminated to multiple persons. While communications such as bulk emails or algorithm-based messages are nominally directed at or “addressed to” only one person, they are in fact widely disseminated to numerous investors and therefore would be subject to the final rule.[70] Similarly, customizing a template presentation or mass mailing by filling in the name of an investor and/or including other basic information about the investor would not result in a one-on-one communication.

Likewise, an adviser cannot use duplicate inserts in an otherwise customized communication in an effort to circumvent application of the rule.[71] For example, if an adviser maintains a database of performance information inserts or tables that it uses in otherwise customized investor communications, the adviser must treat the duplicated inserts as advertisements subject to the rule. Of course, if the adviser provides an existing investor with performance information pertaining to the investor's account, the rule would not apply because this is a one-on-one communication.[72]

One commenter expressed concern that the public dissemination of a seemingly one-on-one communication could subject the communication to the final rule.[73] We believe that if, for example, an adviser responds to a request for proposal (“RFP”) from an entity and the entity subsequently makes such responses available to the public pursuant to a Freedom of Information Act request or other public disclosure requirements, this would not be an advertisement merely by virtue of the entity's disclosure.[74] An adviser should consider adopting compliance policies and procedures that are reasonably designed to determine whether a communication nominally directed to a single person is actually a communication to more than one person, or contains duplicated inserts as part of that communication. In these circumstances, the duplicated information is an advertisement because it is sent to more than one person and would not qualify for the exclusion.

Because of the specific concerns raised by hypothetical performance, hypothetical performance information would not qualify for the one-on-one exclusion unless provided in response to an unsolicited investor request or to a private fund investor.[75] Hypothetical performance included in all other one-on-one communications that offer investment advisory services with regard to securities must be presented in accordance with the requirements discussed below.

We proposed a similar approach for hypothetical performance provided in response to an unsolicited request under the proposed definition of advertisement.[76] Some commenters suggested that the Commission permit an adviser to provide hypothetical performance in response to unsolicited requests to eliminate the need to assess the requirements related to hypothetical performance.[77] These commenters stated that the need to assess these requirements would slow down the flow of information to investors, require investors to provide more information earlier in the diligence process, or limit the hypothetical performance information shared in response to such an unsolicited request. Some commenters stated that private fund investors often seek hypothetical performance information, particularly targets and projections, to evaluate private fund investments.[78] After considering these comments, we believe that, in most circumstances, the protections for hypothetical performance should be available to investors receiving communications that include offers of investment advisory services with regard to securities, to the extent such offers include hypothetical performance information. We believe our modifications to the first prong of the definition of advertisement and to the requirements for presenting hypothetical performance, discussed below, will reduce the associated compliance burdens for providing hypothetical performance information to investors and will, therefore, alleviate some of commenters' concerns.

However, where an investor affirmatively seeks hypothetical performance information from an investment adviser and the investment adviser has not directly or indirectly solicited the request, hypothetical performance information provided in response to the request will be excluded from the definition of advertisement under the final rule.[79] In the case of an unsolicited request, an investor seeks hypothetical performance information for the investor's own purposes, rather than responding to a communication disseminated by an adviser offering its investment advisory services with regard to securities. Similarly, where the hypothetical performance information is provided in a one-on-one communication to a private fund investor, we believe a private fund investor will have the ability and opportunity to ask questions and assess the limitations of this information. In these limited circumstances, we do not believe it is necessary to treat the hypothetical performance information as an advertisement subject to the rule.[80]

iii. Offers Investment Advisory Services With Regard to Securities to Prospective Clients or Investors in a Private Fund Advised by the Investment Adviser

The marketing rule's definition of “advertisement” includes communications that offer the investment adviser's investment advisory services. As discussed in more detail below, we are implementing a number of changes from the proposal, which would have defined advertisements to include communications that offer or promote the investment adviser's investment advisory services or that seek to obtain or retain one or more investment advisory clients or investors in any pooled investment vehicle advised by the investment adviser.[81] First, we are limiting the application of this element of the definition to communications directed to prospective clients or prospective private fund investors, rather than existing clients or private fund investors to avoid an overbroad application of the rule. Accordingly, this aspect of the final rule will retain the current rule's scope.

Second, we also are not adopting the “or promote” wording from the proposed definition of advertisement. Commenters generally opposed including the term “promote,” suggesting that this term could expand the definition of “advertisement” to cover certain materials not subject to the current rule,[82] the text of which is limited to communications that “offer” advisory services.[83] As we indicated in the proposal, the “offer or promote” clause reflects the current rule's application and was designed to capture communications that are commonly considered advertisements.[84] We added the “or promote” wording to the proposed definition for clarity, but after considering comments we realize this wording may instead cause confusion. For example, commenters sought clarification that statements about an advisory firm's culture, philanthropy, or community activity would not fall within the definition of advertisement.[85] We did not intend for our proposed definition and the inclusion of the term “promote” to include such communications. Accordingly, the final rule will not include the term “promote” as it is our intent to retain the current rule's scope in this respect.[86]

Third, consistent with the current rule, we are limiting the application of the definition to offers about an investment adviser's investment advisory services with regard to securities. We were persuaded by commenters who urged us to retain the current rule's scope, arguing that expanding the definition to cover services that are not related to securities could result in an overbroad application of the rule.[87] Importantly, however, the anti-fraud provisions of the Act and related rules continue to apply to an adviser's advertisements and other communications about its other non-securities related services.[88]

Finally, the definition will not include communications that seek to obtain one or more investment advisory clients or investors in any pooled investment vehicle advised by the investment adviser. We determined that this clause was superfluous of the rest of the definition; we believe these communications are captured within an adviser's offer of investment advisory services with regard to securities to prospective investors in a private fund advised by the adviser.[89]

iv. Offers New Investment Advisory Services With Regard to Securities to Current Clients or Investors in a Private Fund Advised by the Investment Adviser

The proposed definition of “advertisement” included communications that seek “to obtain or retain” investors. Commenters generally stated that the “or retain” clause would unnecessarily include communications made in the ordinary course of an adviser providing services to current investors as all communications with current investors are, at least in part, designed to both service and retain investors.[90]

Several commenters asked us to confirm the scope of the definition as applied to communications with existing investors.[91] For example, some commenters suggested an exclusion for all communications with existing investors,[92] while others supported a more limited exclusion for routine investor communications.[93] Commenters generally agreed that the rule should treat communications with existing investors that offer new or additional advisory services as advertisements.[94] Commenters that supported a complete or partial exclusion for communications to existing investors stated that such communications are part of the advisory service and not advertisements.[95]

We agree that the rule should treat only those communications that offer new or additional advisory services with regard to securities to current investors as advertisements because they raise the same concerns as other advertisements. Our intent is not to chill ordinary course communications with current investors. We believe that other protections prevent advisers from engaging in activities that mislead or deceive existing investors.[96] For example, existing and prospective advisory clients receive the anti-fraud protections of the Advisers Act and an adviser's fiduciary duty.[97] Accordingly, under the final rule a communication to a current investor is an advertisement when it offers new or additional investment advisory services with regard to securities. We believe that this modification will allow advisers to continue to provide current investors with timely information regarding their accounts and the market without subjecting those communications to the marketing rule.[98]

In summary, we view an adviser seeking to offer new or additional investment advisory services with regard to securities to current investors as posing the same risks to investors as an adviser seeking to offer such services to new investors and therefore we believe this activity warrants the same treatment under the final marketing rule.

v. Brand Content, General Educational Material, and Market Commentary

Other commenters asked us to confirm that brand content, general educational material, and market commentary are not advertisements under the rule.[99] Whether a communication is an advertisement depends on the facts and circumstances (e.g., whether the communication “offers” the adviser's investment advisory services with regard to securities). Generally, generic brand content, educational material, and market commentary would not meet the revised definition of an advertisement.

Brand content. Determining whether a communication including “brand” content (e.g., displays of the advisory firm name in connection with sponsoring sporting events, supporting community service activities, or supporting philanthropic efforts) is an advertisement would depend on the facts and circumstances.[100] If such a communication is designed to raise the profile of the adviser generally, but does not offer any investment advisory services with regard to securities, the communication would not fall within the definition of an advertisement under the rule. For example, a communication that simply notes that an event is “brought to you by XYZ Advisers” would not qualify as an advertisement, as it is not offering any advisory services with regard to securities.

General educational information and market commentary. We believe that the same analysis applies for communications that provide only general educational information and market commentary.[101] Educational communications that are limited to providing general information about investing, such as information about types of investment vehicles, asset classes, strategies, certain geographic regions, or commercial sectors, do not constitute offers of an adviser's investment advisory services with regard to securities.

Similarly, materials that provide an adviser's general market commentary (including during press interviews) are unlikely to offer advisory services with regard to securities. Market commentary aims to inform current and prospective investors, including private fund investors, of market and regulatory developments in the broader financial ecosystem. These materials also help current investors interpret market and regulatory shifts by providing context when reviewing investments in their portfolios, and educate investors.[102] In contrast, for example, we would view an article or white paper that provides general market commentary and concludes with a description of how the adviser's securities-related services can help prospective investors invest in the market as offering the adviser's services. Accordingly, that portion of the white paper would be an advertisement.

b. Exclusions

The rule will generally exclude two types of communications from the first prong of the definition of advertisement: (i) Extemporaneous, live, oral communications; and (ii) information required by statute or regulation.[103]

i. Extemporaneous, Live, Oral Communications

In a change from the proposal, the definition of advertisement will not include extemporaneous, live, oral communications, regardless of whether they are broadcast and regardless of whether they take place in a one-on-one context and involve discussion of hypothetical performance. We proposed an exclusion for live, oral communications that are not broadcast on radio, television, the internet, or any other similar medium. Commenters generally supported the exclusion, but had questions about certain aspects. For example, some commenters expressed concern about the treatment of written materials that accompany or are used to prepare for oral presentations, stating that treating such materials as advertisements would hamper an adviser's ability to prepare for a presentation.[104] Other commenters questioned the scope of the exclusion, with some arguing that it was too narrow [105] and others arguing that it was too broad.[106]

The goal of the exclusion for live, oral communications was to avoid treating extemporaneous statements as advertisements, in light of the difficulties in ensuring that they comply with the requirements of the rule, and to avoid chilling adviser communications with investors. If remarks are extemporaneous, they cannot be simultaneously monitored for regulatory compliance, and to require otherwise may simply cause advisers to cease extemporaneous speech to the overall detriment of investors. However, we believe that communications prepared in advance can and should be subject to the rule. Accordingly, the final exclusion will apply only to extemporaneous, live, oral communications.[107]

Extemporaneous communications do not include prepared remarks or speeches, such as those delivered from scripts.[108] In addition, slides or other written materials that are distributed or presented to the audience would also be included as advertisements if they otherwise meet the definition. On the other hand, live, extemporaneous, oral discussions with a group of investors or interviews with the press that are not based on prepared remarks will be eligible for the exclusion. This approach aligns with the purpose of the exclusion, which is to avoid a chilling effect on extemporaneous, oral speech that might occur if such communications were required to comply with the requirements of the final rule.

Some commenters recommended that we further expand the exclusion to apply to certain written communications.[109] While we appreciate that other modern communication methods facilitate instantaneous written conversations (e.g., text messages, chat), this exclusion is limited to extemporaneous, live, oral communications, because in those circumstances a speaker often does not have sufficient time to edit and reflect on the content of the communication.[110]

Some commenters suggested that we exclude all broadcast communications and adopt an approach similar to FINRA.[111] Commenters also sought guidance on the meaning of the following terms: “broadcast” [112] and “widely disseminated.” [113] In response to commenters' concerns, we are not adopting the requirement that the live, oral communication is “not broadcast.” We believe the concerns that prompted this exclusion apply equally to extemporaneous, live, oral communications regardless of whether they are broadcast. We also believe that the exclusion should not allow an adviser to avoid application of the rule for a previously prepared live, oral communication in a non-broadcast setting, such as a luncheon seminar designed to attract new investors. In addition, commenters raised a variety of concerns with identifying whether a communication is broadcast in light of modern media tools, suggesting that line drawing as to when a communication is broadcast may be challenging in practice.[114] As a result, the exclusion will apply to a broadcast communication, such as a webcast, that is an extemporaneous, live, oral communication.

The exclusion will apply to “live” oral communications, as proposed. Accordingly, previously recorded oral communications disseminated by the adviser would not qualify as live because the adviser had time to review and edit the recording before such dissemination and thus can ensure compliance with the marketing rule. In these circumstances, an adviser would need to treat its subsequent dissemination of the recording as an advertisement under the rule if the recording offers the adviser's investment advisory services with regard to securities. However, we believe that an oral communication would be “live” even if there is a time lag (e.g., streaming delay), a translation program is used, or adaptive technology is used to create a personal transcription (e.g., voice to text technology or other tools that assist the deaf, hard-of-hearing, or hearing loss communities).

ii. Information Contained in a Statutory or Regulatory Notice, Filing, or Other Required Communication

The final rule excludes from the definition of advertisement “[i]nformation contained in a statutory or regulatory notice, filing, or other required communication, provided that such information is reasonably designed to satisfy the requirements of such notice, filing, or other required communication.” [115] In response to commenters, we have broadened the proposed exclusion, which would have applied to “[a]ny information required to be contained in a statutory or regulatory notice, filing, or other communication.” [116] Commenters generally supported the proposed exclusion,[117] but recommended we expand it to ease compliance burdens and avoid duplicative regulation that would have resulted from applying another layer of review to mandatory filings.[118]

Specifically, commenters stated that compliance personnel would have difficulty determining exactly which information contained in a regulatory filing is strictly and explicitly required by applicable law versus which information is not (and would therefore be subject to the rule). In response to these comments, we broadened the exclusion to cover information in a statutory or regulatory, notice, filing or other required communication, provided the information is reasonably designed to satisfy the requirements, rather than information required to be contained in such a communication.[119] For example, information reasonably designed to satisfy the requirements of Form ADV Part 2 or Form CRS will not be an advertisement.[120]

This exclusion will apply to information that an adviser provides to an investor under any statute or regulation under Federal or state law, including rules promulgated by regulatory agencies. We generally do not believe that communications that are prepared as a requirement of statutes, rules, or regulations should be viewed as advertisements under the final rule.[121] However, if an adviser includes in such a communication information that is not reasonably designed to satisfy its obligations under applicable law, and such additional information offers the adviser's investment advisory services with regard to securities, then that information will be considered an “advertisement” for purposes of the rule.

3. Definition of Advertisement: Compensated Testimonials and Endorsements, Including Solicitations

To reflect the merger of the two rules, the final rule's definition of “advertisement” includes a new second prong that applies to “any endorsement or testimonial for which an investment adviser provides compensation, directly or indirectly” subject to an exclusion for certain regulatory notices, filings, and other required communications.[122] A compensated testimonial or endorsement will meet the definition of advertisement's second prong regardless of whether the communication is made orally or in writing, to one or more persons.[123] By contrast, an uncompensated testimonial or endorsement would have to meet the elements of prong one in order to be considered an “advertisement.”

a. Definitions of Testimonial and Endorsement

The final definition of testimonial includes any statement by a current client or private fund investor about the client's or private fund investor's experience with the investment adviser or its supervised persons.[124] The definition of endorsement includes any statement by a person other than a current client or private fund investor that indicates approval, support, or recommendation of the investment adviser or its supervised persons or describes that person's experience with the investment adviser or its supervised persons.[125] This scope of how these activities are defined is similar to the proposal, with a few changes described below, including adding solicitation and referral activities drawn from the proposed definition of solicitor.

These definitions include statements about the adviser's “supervised persons,” rather than the proposed inclusion of statements about the adviser's “advisory affiliates.” [126] One commenter recommended this change, stating that an endorsement or testimonial regarding a supervised person is more likely to provide relevant information to an investor than a statement about an adviser's advisory affiliate.[127]

We received a variety of comments about the statements these definitions would capture. One commenter supported a broad approach that would include statements about an adviser's traits, such as trustworthiness, to reflect the commenter's belief that prospective clients typically select an adviser based on emotion.[128] Another commenter requested that we limit the definitions to include only statements that explicitly discuss the adviser's services or capabilities as an adviser.[129]

Under the final marketing rule, testimonials and endorsements will include opinions or statements by persons about the investment advisory expertise or capabilities of the adviser or its supervised persons.[130] Testimonials and endorsements also include statements in an advertisement about an adviser or its supervised person's qualities (e.g., trustworthiness, diligence, or judgment) or expertise or capabilities in other contexts, when the statements suggest that the qualities, capabilities, or expertise are relevant to the advertised investment advisory services. We believe that an investor would likely perceive these statements as relevant to the adviser's investment advisory services.[131]

The definitions of testimonial and endorsement under the final rule also include solicitation and referral activities drawn from the proposed definition of solicitor.[132] After considering comments on the overlapping scope of testimonials, endorsements, and solicitations under the proposed advertising and solicitation rules, we are adding solicitation activities to the definitions of testimonial and endorsement. The definition of testimonial includes any statement by a current client or private fund investor that directly or indirectly solicits any investor to be the adviser's client or a private fund investor, or refers any investor to be the adviser's client or a private fund investor. The definition of endorsement includes any such statements by a person other than a current client or private fund investor. This change will address compensated testimonials and endorsements under one rule with one set of conditions. For example, a person providing an endorsement or testimonial under the final rule might be a firm that solicits for an adviser (such as a broker-dealer or a bank), an individual at a soliciting firm who engages in solicitation activities for an adviser (such as a bank representative or an individual registered representative of a broker-dealer), or both. Other examples could be an unaffiliated fund-of-funds or a feeder fund that solicits investors in an underlying fund or a master fund, respectively.

b. Cash and Non-Cash Compensation

The second prong of the final marketing rule's definition of advertisement is triggered by any form of compensation—whether cash or non-cash—that an adviser provides, directly or indirectly, for an endorsement or testimonial. This mirrors the types of compensation that we stated would trigger the proposed solicitation rule and the proposed advertising rule's compensation disclosure requirement in connection with a testimonial, endorsement, or third-party rating.[133] As we stated about both proposed rules, compensation an adviser provides, directly or indirectly, for these activities can incentivize a person to provide a positive statement about, solicit an investor for, or refer an investor to, the investment adviser.[134] Therefore, we believe that the marketing rule's protections should apply.

Some commenters agreed that non-cash compensation creates the same conflicts of interest as cash compensation for solicitation.[135] These commenters also agreed that investors should be made aware of the solicitor's conflict of interest regardless of the form of compensation. Other commenters, however, raised concerns about extending the rule to cover certain forms of non-cash compensation, such as gifts and entertainment,[136] or non-transferable advisory fee waivers in connection with refer-a-friend arrangements.[137] Some commenters argued that the final rule should only apply to solicitations for which the adviser provides incentive-based compensation tied to the funding of an advisory account and the solicitation activities are directed at specific clients.[138] Commenters generally opposed applying the proposed solicitation rule to communications to investors in private funds, which we address below.[139]

Forms of compensation under the final marketing rule will include fees based on a percentage of assets under management or amounts invested, flat fees, retainers, hourly fees, reduced advisory fees, fee waivers, and any other methods of cash compensation, and cash or non-cash rewards that advisers provide for endorsements and testimonials, including referral and solicitation activities.[140] They also include directed brokerage that compensates brokers for soliciting investors,[141] sales awards or other prizes, gifts and entertainment, such as outings, tours, or other forms of entertainment that an adviser provides as compensation for testimonials and endorsements. In addition, compensated endorsements and testimonials may or may not be contingent on the endorsement or testimonial resulting in a new advisory relationship or a new investment in a private fund. We believe that non-cash compensation, including forms of entertainment, can incentivize persons to provide a positive statement about an adviser, or make a referral or solicitation on an adviser's behalf and should be included in the rule to make clients aware of such incentive. Whether an adviser provides cash or non-cash compensation in exchange for a testimonial or endorsement depends on the particular facts and circumstances.[142]

Some commenters requested that we exclude training or meetings that educate solicitors about the adviser's services, even if there are some incidental benefits associated with such training.[143] We continue to believe, as we stated in the 2019 Proposing Release, that attendance at training and education meetings, including company-sponsored meetings such as annual conferences, will not be non-cash compensation, provided that attendance at these meetings or trainings is not provided in exchange for solicitation activities.[144]

Some commenters also raised concerns about potentially conflicting regulations for advisers dually registered as broker-dealers with respect to the inclusion of sales awards as non-cash compensation under the proposed solicitation rule.[145] While we acknowledge that other Commission rules for broker-dealers address concerns underlying non-cash compensation in the context of recommendations, the final marketing rule covers a broader range of activities and types of promoters.[146] Thus, we do not believe that an exemption for sales awards or contests from the final marketing rule would be appropriate on these grounds. As discussed further below, however, we are adopting a partial exemption for broker-dealers from the rule's disqualification provisions. We are also adopting partial exemptions from the disclosure provisions when a broker-dealer provides a testimonial or endorsement to a retail customer that is a recommendation subject to Regulation Best Interest (“Regulation BI”) under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (the “Exchange Act”) and from certain disclosure requirements when a broker-dealer provides a testimonial or endorsement to a person that is not a retail customer (as that term is defined in Regulation BI).[147]

Other commenters stated non-cash compensation could capture benefits that advisers provide in the ordinary course of business unrelated to any solicitation activity.[148] Relatedly, some commenters considered our proposed view of “indirect” compensation overly broad, particularly with respect to non-cash compensation.[149] These commenters recommended that we apply the final rule only to compensation an adviser provides to a solicitor after its solicitation activities, unless the solicitation agreement between the adviser and solicitor specifically includes compensation provided prior to the solicitation; or replace the solicitation rule's reference to compensation that an adviser provides “indirectly” with compensation that is direct or “in connection with solicitation activities.” [150] Others expressed concerns that, under our proposed solicitation rule, every mutually beneficial arrangement between an investment adviser and a potential facilitator of client relationships would be subject to scrutiny for indicia of quid pro quo solicitation.[151]

We believe the timing of compensation relative to an endorsement or testimonial is relevant in determining whether an adviser is providing compensation for the testimonial or endorsement. In addition, we believe that there will be a mutual understanding of a quid pro quo, whether explicit or inferred based on facts and circumstances, for most compensated endorsements or testimonials.[152] However, we decline to draw bright lines around either the timing of the compensation or the establishment of a mutual understanding. We believe such bright lines would unnecessarily limit the final rule and would encourage advisers to structure their arrangements to avoid application of the rule in situations where it would otherwise apply. In addition, we believe that in many cases compensation will be in connection with testimonials and endorsements. We decline to remove the word “indirectly” from the rule for the same reasons discussed above.[153]

c. Activities That Constitute a Testimonial or Endorsement

Some commenters requested guidance on whether certain activities would constitute solicitation or referral activities under the proposed amendments to the solicitation rule.[154] Since the combined marketing rule includes statements that solicit investors for, or refer investors to, an investment adviser as testimonials or endorsements, we are addressing these comments in the context of these definitions.

For example, some commenters questioned whether lead-generation firms or adviser referral networks (collectively, “operators”) would fall into the scope of the rule. One commenter described these operators as networks operated by non-investors where an adviser compensates the operator to solicit investors for, or refer investors to, the adviser.[155] Another commenter described these operators as for-profit or non-profit entities that make third-party advisory services (such as model portfolio providers) accessible to investors, and stated that the operators do not promote or recommend particular services or products accessible on the platform.[156] In both examples, the operator's website likely meets the final marketing rule's definition of endorsement. An operator may tout the advisers included in its network, and/or guarantee that the advisers meet the network's eligibility criteria. In addition, because operators typically offer to “match” an investor with one or more advisers compensating it to participate in the service, operators typically engage in solicitation or referral activities.[157]

Similarly, a blogger's website review of an adviser's advisory service would be a testimonial or an endorsement under the final marketing rule because it indicates approval, support, or a recommendation of the investment adviser, or because it describes its experience with the adviser.[158] If the adviser directly or indirectly compensates the blogger for its review, for example by paying the blogger based on the amount of assets deposited in new accounts from client referrals or the number of accounts opened, the testimonial or endorsement will be an advertisement under the definition's second prong.[159] Depending on the facts and circumstances, a lawyer or other service provider that refers an investor to an adviser, even infrequently, may also meet the rule's definition of testimonial or endorsement.

On the other hand, where an adviser pays a third-party marketing service or news publication to prepare content for and/or disseminate a communication, we generally would not treat this communication as an endorsement under the second prong of the definition of “advertisement.” [160] Similarly, a non-investor selling an adviser a list containing the names and contact information of prospective investors typically would not, without more, meet the definition of endorsement.[161] This activity typically would not fall within the plain text of the definition of endorsement (e.g., the seller does not indicate approval, support, or recommendation of the investment adviser, or describe its experience with the adviser, or engage in the solicitation or referral activities described therein).

One commenter requested an exclusion from the definition of solicitor under the proposed solicitation rule for an investment consultant that administers a RFP to aid one or more investors in selecting an investment adviser or a private fund investment vehicle.[162] The commenter stated that the investor typically hires the consultant (the “agent”), subject to the understanding that the investor will only enter into a transaction with an investment adviser that agrees to pay the expenses of the agent for providing this service.[163] In these circumstances, we do not believe the adviser typically compensates the agent to endorse the adviser because the investor engages the agent to evaluate the adviser based on criteria that the investor provides.[164]

d. Exclusion for Regulatory Communications; Inclusion of One-on-One and Extemporaneous, Live, Oral Communications

The second prong of the definition of advertisement excludes any information contained in a statutory or regulatory notice, filing, or other required communication, provided that such information is reasonably designed to satisfy the requirements of such notice, filing, or other required communication.[165] As with the same exclusion in the first prong of the definition, this exclusion reflects our belief that communications that are prepared as a requirement of statutes, rules, or regulations should not be viewed as advertisements under the rule.

Unlike the first prong of the definition of advertisement, however, this prong does not exclude extemporaneous, live, oral communications or one-on-one communications. These types of communications are precisely what the second prong of the definition seeks to address, along with other types of endorsement and testimonial activities. The current solicitation rule has also addressed these types of communications. In addition, the second prong does not exclude communications that include hypothetical performance information.