AGENCY:

National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Commerce.

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

NMFS's Office of Protected Resources (OPR), upon request from NMFS's Alaska Fisheries Science Center (AFSC), hereby issues regulations to govern the unintentional taking of marine mammals incidental to fisheries research conducted in multiple specified geographical regions over the course of five years. These regulations, which allow for the issuance of Letters of Authorization (LOA) for the incidental take of marine mammals during the described activities and specified timeframes, prescribe the permissible methods of taking and other means of effecting the least practicable adverse impact on marine mammal species or stocks and their habitat, as well as requirements pertaining to the monitoring and reporting of such taking.

DATES:

Effective from October 7, 2019, through October 7, 2024.

ADDRESSES:

A copy of AFSC's application and supporting documents, as well as a list of the references cited in this document, may be obtained online at: www.fisheries.noaa.gov/action/incidental-take-authorization-noaa-fisheries-afsc-fisheries-and-ecosystem-research. In case of problems accessing these documents, please call the contact listed below.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Ben Laws, Office of Protected Resources, NMFS, (301) 427-8401.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Purpose and Need for Regulatory Action

These regulations establish a framework under the authority of the MMPA (16 U.S.C. 1361 et seq.) to allow for the authorization of take of marine mammals incidental to the AFSC's fisheries research activities in the Gulf of Alaska, Bering Sea, and Arctic Ocean, and, by AFSC's request, also includes fisheries research activities of the International Pacific Halibut Commission (IPHC), which occur in the Bering Sea, Gulf of Alaska, and off of the U.S. west coast.

We received an application from the AFSC requesting five-year regulations and authorization to take multiple species of marine mammals. Take would occur by Level B harassment incidental to the use of active acoustic devices, as well as by visual disturbance of pinnipeds, and by Level A harassment, serious injury, or mortality incidental to the use of fisheries research gear. Please see “Background” below for definitions of harassment.

Legal Authority for the Action

Section 101(a)(5)(A) of the MMPA (16 U.S.C. 1371(a)(5)(A)) directs the Secretary of Commerce to allow, upon request, the incidental, but not intentional taking of small numbers of marine mammals by U.S. citizens who engage in a specified activity (other than commercial fishing) within a specified geographical region for up to five years if, after notice and public comment, the agency makes certain findings and issues regulations that set forth permissible methods of taking pursuant to that activity and other means of effecting the “least practicable adverse impact” on the affected species or stocks and their habitat (see the discussion below in the “Mitigation” section), as well as monitoring and reporting requirements. Section 101(a)(5)(A) of the MMPA and the implementing regulations at 50 CFR part 216, subpart I provide the legal basis for issuing this rule containing five-year regulations, and for any subsequent LOAs. As directed by this legal authority, the regulations contain mitigation, monitoring, and reporting requirements.

Summary of Major Provisions Within the Regulations

Following is a summary of the major provisions of these regulations regarding AFSC fisheries research activities. These measures include:

- Required monitoring of the sampling areas to detect the presence of marine mammals before deployment of certain research gear.

- Required implementation of the mitigation strategy known as the “move-on rule mitigation protocol” which incorporates best professional judgment, when necessary during certain research fishing operations.

Background

Section 101(a)(5)(A) of the MMPA (16 U.S.C. 1361 et seq.) directs the Secretary of Commerce (as delegated to NMFS) to allow, upon request, the incidental, but not intentional, taking of small numbers of marine mammals by U.S. citizens who engage in a specified activity (other than commercial fishing) within a specified geographical region if certain findings are made, regulations are issued, and notice is provided to the public.

An authorization for incidental takings shall be granted if NMFS finds that the taking will have a negligible impact on the species or stock(s), will not have an unmitigable adverse impact on the availability of the species or stock(s) for subsistence uses (where relevant), and if the permissible methods of taking and requirements pertaining to the mitigation, monitoring and reporting of such takings are set forth.

NMFS has defined “negligible impact” in 50 CFR 216.103 as an impact resulting from the specified activity that cannot be reasonably expected to, and is not reasonably likely to, adversely affect the species or stock through effects on annual rates of recruitment or survival.

NMFS has defined “unmitigable adverse impact” in 50 CFR 216.103 as an impact resulting from the specified activity:

(1) That is likely to reduce the availability of the species to a level insufficient for a harvest to meet subsistence needs by: (i) Causing the marine mammals to abandon or avoid hunting areas; (ii) directly displacing subsistence users; or (iii) placing physical barriers between the marine mammals and the subsistence hunters; and

(2) That cannot be sufficiently mitigated by other measures to increase the availability of marine mammals to allow subsistence needs to be met.

The MMPA states that the term “take” means to harass, hunt, capture, kill or attempt to harass, hunt, capture, or kill any marine mammal.

Except with respect to certain activities not pertinent here, the MMPA defines “harassment” as: Any act of pursuit, torment, or annoyance which (i) has the potential to injure a marine mammal or marine mammal stock in the wild (Level A harassment); or (ii) has the potential to disturb a marine mammal or marine mammal stock in the wild by causing disruption of behavioral patterns, including, but not limited to, migration, breathing, nursing, breeding, feeding, or sheltering (Level B harassment).

Summary of Request

On June 28, 2016, we received an adequate and complete request from AFSC for authorization to take marine mammals incidental to fisheries research activities. On October 18, 2016 (81 FR 71709), we published a notice of receipt of AFSC's application in the Federal Register, requesting comments and information related to the AFSC request for thirty days. We received comments jointly from The Humane Society of the United States and Whale and Dolphin Conservation (HSUS/WDC). Subsequently, AFSC presented substantive revisions to the application, including revisions to the take authorization request as well as incorporation of the IPHC fisheries research activities. We received this revised application, which was determined to be adequate and complete, on September 6, 2017. We then published a notice of its receipt in the Federal Register, requesting comments and information for thirty days, on September 14, 2017 (82 FR 43223). We received no comments in response to this second review period. The original comments received from HSUS/WDC are available online at: www.fisheries.noaa.gov/action/incidental-take-authorization-noaa-fisheries-afsc-fisheries-and-ecosystem-research and were considered in development of the proposed rule. We published a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking in the Federal Register on August 1, 2018 (83 FR 37638) and requested comments and information from the public. Please see “Comments and Responses,” below.

AFSC conducts fisheries research using trawl gear used at various levels in the water column, hook-and-line gear (including longlines with multiple hooks), gillnets, and other gear. If a marine mammal interacts with gear deployed by AFSC, the outcome could potentially be Level A harassment, serious injury (i.e., any injury that will likely result in mortality), or mortality. Although any given gear interaction could result in an outcome less severe than mortality or serious injury, we do not have sufficient information to allow parsing these potential outcomes. Therefore, AFSC presents a pooled estimate of the number of potential incidents of gear interaction and, for analytical purposes we assume that gear interactions would result in serious injury or mortality. AFSC also uses various active acoustic devices in the conduct of fisheries research, and use of some devices has the potential to result in Level B harassment of marine mammals. Level B harassment of pinnipeds hauled out may also occur, as a result of visual disturbance from vessels conducting AFSC research.

AFSC requested authorization to take individuals of 19 species by Level A harassment, serious injury, or mortality (hereafter referred to as M/SI) and of 25 species by Level B harassment. These regulations are effective for five years.

Description of the Specified Activity

Overview

The AFSC collects a wide array of information necessary to evaluate the status of exploited fishery resources and the marine environment. AFSC scientists conduct fishery-independent research onboard NOAA-owned and operated vessels or on chartered vessels. Such research may also be conducted by cooperating scientists on non-NOAA vessels when the AFSC helps fund the research. The AFSC plans to administer and conduct approximately 58 survey programs over the five-year period, within three separate research areas (some survey programs are conducted across more than one research area). The gear types used fall into several categories: towed nets fished at various levels in the water column, longline gear, gillnets and seine nets, traps, and other gear. Only use of trawl nets, longlines, and gillnets are likely to result in interaction with marine mammals. Many of these surveys also use active acoustic devices.

The Federal government has a responsibility to conserve and protect living marine resources in U.S. waters and has also entered into a number of international agreements and treaties related to the management of living marine resources in international waters outside the United States. NOAA has the primary responsibility for managing marine finfish and shellfish species and their habitats, with that responsibility delegated within NOAA to NMFS.

In order to direct and coordinate the collection of scientific information needed to make informed fishery management decisions, Congress created six regional fisheries science centers, each a distinct organizational entity and the scientific focal point within NMFS for region-based Federal fisheries-related research. This research is aimed at monitoring fish stock recruitment, abundance, survival and biological rates, geographic distribution of species and stocks, ecosystem process changes, and marine ecological research. The AFSC is the research arm of NMFS in the Alaska region of the United States. The AFSC conducts research and provides scientific advice to manage fisheries and conserve protected species in the geographic research areas described below and provides scientific information to support the North Pacific Fishery Management Council and other domestic and international fisheries management organizations.

The IPHC, established by a convention between the governments of Canada and the United States, is an international fisheries organization mandated to conduct research on and management of the stocks of Pacific halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis) within the Convention waters of both nations. The Northern Pacific Halibut Act of 1982 (16 U.S.C. 773), which amended the earlier Northern Pacific Halibut Act of 1937, is the enabling legislation that gives effect to the Convention in the United States. Although operating in U.S. waters (and, therefore, subject to the MMPA prohibition on “take” of marine mammals), the IPHC is not appropriately considered to be a U.S. citizen (as defined by the MMPA) and cannot be issued an incidental take authorization. For purposes of MMPA compliance, the AFSC sponsors the IPHC research activities occurring in U.S. waters, with applicable mitigation, monitoring, and reporting requirements conveyed to the IPHC via Letters of Acknowledgement issued by the AFSC pursuant to the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSA).

Fishery-independent data necessary to the management of halibut stocks is collected using longline gear aboard chartered commercial vessels within multiple IPHC regulatory areas, including within U.S. waters of the Bering Sea, Gulf of Alaska, and off the U.S. west coast. The IPHC plans to conduct two survey programs over the five-year period. IPHC activity and requested take authorization is described in Appendix C of AFSC's application.

Dates and Duration

The specified activity may occur at any time during the five-year period of validity of the regulations. Dates and duration of individual surveys are inherently uncertain, based on congressional funding levels for the AFSC, weather conditions, or ship contingencies. In addition, cooperative research is designed to provide flexibility on a yearly basis in order to address issues as they arise. Some cooperative research projects last multiple years or may continue with modifications. Other projects only last one year and are not continued. Most cooperative research projects go through an annual competitive selection process to determine which projects should be funded based on proposals developed by many independent researchers and fishing industry participants.

Specified Geographical Region

The AFSC conducts research in Alaska within three research areas considered to be distinct specified geographical regions: The Gulf of Alaska Research Area (GOARA), the Bering Sea/Aleutian Islands Research Area (BSAIRA), and the Chukchi Sea and Beaufort Sea Research Area (CSBSRA). Please see Figures 2-1 through 2-3 in the AFSC application for maps of the three research areas. We note here that, while the specified geographical regions within which the AFSC operates may extend outside of the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), i.e., into the Canadian EEZ (but not including Canadian territorial waters), the MMPA's authority does not extend into foreign territorial waters. IPHC research activities are carried out within the BSAIRA and GOARA but also within a fourth specified geographical region, i.e., off the U.S. west coast (see Figure C-3 of the AFSC application). The IPHC operates from 36°40′ N (approximately Monterey Bay, California) at the southernmost extension northward to the Canadian border, including U.S. waters within Puget Sound. These areas were described in detail in our Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (83 FR 37638; August 1, 2018); please see that document for further detail.

Detailed Description of Activities

A detailed description of AFSC's planned activities was provided in our Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (83 FR 37638; August 1, 2018) and is not repeated here. No changes have been made to the specified activities described therein.

Comments and Responses

We published a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking in the Federal Register on August 1, 2018 (83 FR 37638), and requested comments and information from the public. During the thirty-day comment period, we received letters from the Marine Mammal Commission (Commission), the Ecological Sciences Communication Initiative (ECO-SCI), and from three private citizens. Of the latter, one comment expressed general opposition, one expressed general support, and one was not relevant to the proposed rulemaking. The remaining comments and our responses are provided here, and the comments have been posted online at: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/action/incidental-take-authorization-noaa-fisheries-afsc-fisheries-and-ecosystem-research. Please see the Commission's comment letter for full rationale behind the recommendations we respond to below. No changes were made to the proposed rule as a result of these comments.

Comment 1: The Commission provides general recommendations—not specific to the proposed AFSC rulemaking—that NMFS develop criteria and guidance for determining when prospective applicants should request taking by Level B harassment from the use of echosounders, other sonars, and sub-bottom profilers and that NMFS formulate a strategy for updating its generic behavioral harassment thresholds for all types of sound sources as soon as possible.

Response: We thank the Commission for its continued interest in these issues. Generally speaking, there has been a lack of information and scientific consensus regarding the potential effects of scientific sonars on marine mammals, which may differ depending on the system and species in question as well as the environment in which the system is operated. We will continue to evaluate the need for applicant guidance specific to the types of acoustic sources mentioned by the Commission.

With regard to revision of existing behavioral harassment criteria, NMFS agrees that this is necessary. NMFS is continuing our examination of the effects of noise on marine mammal behavior and is focused on developing guidance regarding the effects of anthropogenic sound on marine mammal behavior. Behavioral response is a complex question, and NMFS will take the time that is necessary to research and address it appropriately.

Comment 2: The Commission recommends that OPR require AFSC to estimate the numbers of marine mammals taken by Level B harassment incidental to use of active acoustic sources (e.g., echosounders) based on the 120-decibel (dB) rather than the 160-dB root mean square (rms) sound pressure level (SPL) threshold.

Response: Please see our Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (83 FR 37638; August 1, 2018) for discussion related to acoustic terminology and thresholds. The Commission repeats a recommendation made in prior letters concerning proposed authorization of take incidental to use of scientific sonars (such as echosounders). As we have described in responding to those prior comments (e.g., 83 FR 36370), our evaluation of the available information leads us to disagree with this recommendation. After review of the Commission's recommendation in this case, our assessment is unchanged. While the Commission presents certain valid points in attempting to justify their recommendation (e.g., certain sensitive species are known to respond to sound exposures at lower levels), these points do not ultimately support the recommendation.

First, we provide some necessary background on implementation of acoustic thresholds. NMFS has historically used generalized acoustic thresholds based on received levels to predict the occurrence of behavioral harassment, given the practical need to use a relatively simple threshold based on information that is available for most activities. Thresholds were selected in consideration largely of measured avoidance responses of mysticete whales to airgun signals and to industrial noise sources, such as drilling. The selected thresholds of 160 dB rms SPL and 120 dB rms SPL, respectively, have been extended for use since then for estimation of behavioral harassment associated with noise exposure from sources associated with other common activities as well.

Separately, NMFS and the U.S. Navy have historically worked closely together to develop appropriate criteria specific to use of low- and mid-frequency active sonar and underwater explosives. The Commission's reference to the Navy's use of different acoustic harassment criteria is not relevant, as those criteria were developed, and have evolved over time in reflection of available science, with specific reference to military sonar or underwater detonations.

The Commission misinterprets how NMFS characterizes scientific sonars, so we provide clarification here. Sound sources can be divided into broad categories based on various criteria or for various purposes. As discussed by Richardson et al. (1995), source characteristics include strength of signal amplitude, distribution of sound frequency and, importantly in context of these thresholds, variability over time. With regard to temporal properties, sounds are generally considered to be either continuous or transient (i.e., intermittent). Continuous sounds, which are produced by the industrial noise sources for which the 120-dB behavioral harassment threshold was selected, are simply those whose sound pressure level remains above ambient sound during the observation period (ANSI, 2005). Intermittent sounds are defined as sounds with interrupted levels of low or no sound (NIOSH, 1998). Simply put, a continuous noise source produces a signal that continues over time, while an intermittent source produces signals of relatively short duration having an obvious start and end with predictable patterns of bursts of sound and silent periods (i.e., duty cycle) (Richardson and Malme, 1993). It is this fundamental temporal distinction that is most important for categorizing sound types in terms of their potential to cause a behavioral response. For example, Gomez et al. (2016) found a significant relationship between source type and marine mammal behavioral response when sources were split into continuous (e.g., shipping, icebreaking, drilling) versus intermittent (e.g., sonar, seismic, explosives) types. In addition, there have been various studies noting differences in responses to intermittent and continuous sound sources for other species (e.g., Neo et al., 2014; Radford et al., 2016; Nichols et al., 2015).

Sound sources may also be categorized based on their potential to cause physical damage to auditory structures and/or result in threshold shifts. In contrast to the temporal distinction discussed above, the most important factor for understanding the differing potential for these outcomes across source types is simply whether the sound is impulsive or not. Impulsive sounds, such as those produced by airguns, are defined as sounds which are typically transient, brief (< 1 sec), broadband, and consist of a high peak pressure with rapid rise time and rapid decay (ANSI, 1986; NIOSH, 1998). These sounds are generally considered to have greater potential to cause auditory injury and/or result in threshold shifts. Non-impulsive sounds can be broadband, narrowband or tonal, brief or prolonged, continuous or intermittent, and typically do not have the high peak pressure with rapid rise/decay time that impulsive sounds do (ANSI, 1995; NIOSH, 1998). Because the selection of the 160-dB behavioral threshold was focused largely on airgun signals, it has historically been commonly referred to as the “impulse noise” threshold (including by NMFS). However, this longstanding confusion in terminology—i.e., the erroneous impulsive/continuous dichotomy—presents a narrow view of the sound sources to which the thresholds apply, and inappropriately implies a limitation in scope of applicability for the 160-dB behavioral threshold in particular.

An impulsive sound is by definition intermittent; however, not all intermittent sounds are impulsive. Many sound sources for which it is generally appropriate to consider the authorization of incidental take are in fact either impulsive (and intermittent) (e.g., impact pile driving) or continuous (and non-impulsive) (e.g., vibratory pile driving). However, scientific sonars present a less common case where the sound produced is considered intermittent but non-impulsive. Herein lies the crux of the Commission's argument, i.e., that because scientific sonars used by NMFS's science centers are not impulsive sound sources, they must be assessed using the 120-dB behavioral threshold appropriate for continuous noise sources. However, given the existing paradigm—dichotomous thresholds appropriate for generic use in evaluating the potential for behavioral harassment resulting from exposure to continuous or intermittent sound sources—the Commission does not adequately explain why potential harassment from an intermittent sound source should be evaluated using a threshold developed for use with continuous sound sources. As we have stated in prior responses to this recommendation, consideration of the preceding factors leads to a conclusion that the 160-dB threshold is more appropriate for use than is the 120-dB threshold.

As noted above, the Commission first claims generically that we are using an incorrect threshold, because scientific sonars do not produce impulse noise. However, in bridging the gap from this generic assertion to their specific recommendation that the 120-dB continuous noise threshold should be used, the Commission makes several leaps of logic that we address here. The Commission's justification is in large part seemingly based on citation to examples in the literature of the most sensitive species responding at lower received levels to sources dissimilar to those considered here. There are three critical errors in this approach.

First, the citation of examples of animals “responding to sound” does not equate to behavioral harassment, as defined by the MMPA. As noted above under “Background,” the MMPA defines Level B harassment as acts with the potential to disturb a marine mammal by causing disruption of behavioral patterns. While it is possible that some animals do in fact experience Level B harassment upon exposure to intermittent sounds at received levels less than the 160-dB threshold, this is not in and of itself adequate justification for using a lower threshold. Implicit in the use of a step function for quantifying behavioral harassment is the realistic assumption, due to behavioral context and other factors, that some animals exposed to received levels below the threshold will in fact experience harassment, while others exposed to levels above the threshold will not. Moreover, a brief, transient behavioral response should not necessarily be considered as having the potential to disturb by disrupting behavioral patterns.

Many of the examples given by the Commission demonstrate mild responses, but not behavioral changes more likely to indicate Level B harassment. For example, the Commission discusses two studies (Quick et al., 2017; Cholewiak et al., 2017) that describe responses to one of the same sources considered here (the EK60 echosounder). We addressed Quick et al. (2017) in our Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, describing the authors' findings that, while tagged pilot whales increased heading variance during exposure to the EK60, tag data did not show an overt response to the echosounder or a change to foraging behavior. (Digital acoustic recording tags were attached to study animals; EK60 signals were within audible range for the animals with received levels ranging from 117-125 dB). Similarly, the authors report that visual observations of behavior did not indicate any dramatic response, unusual behaviors, changes in heading, or cessation of biologically important behavior such as feeding. No evidence is presented that could be reasonably construed as Level B harassment. Cholewiak et al. (2017) describe responses of beaked whales to the EK60 echosounder, finding that they were significantly less likely to be detected acoustically while echosounders were active. However, it is not clear that this response should be considered as Level B harassment when considered in context of what is likely a brief, transient effect given the mobile nature of the surveys and the fact that some beaked whale populations are known to have high site fidelity. (We note that the Commission cites these studies as support for Lurton and DeRuiter (2011)'s suggestion of 130 dB as a reasonable behavioral response threshold. Given that a “behavioral response threshold” does not equate to a behavioral harassment threshold, we are unsure about the intended implication. In addition, Lurton and DeRuiter casually offer this threshold as a result of a “conservative approach” using “response thresholds of the most sensitive species studied to date.” NMFS does not agree with any suggestion that this equates to an appropriate behavioral harassment threshold). Watkins and Schevill (1975) note that sperm whales “temporarily interrupted” sound production in response to sound from pingers. No avoidance behavior was observed, and the authors note that “there appeared to be no startle reactions, no sudden movements, or changes in the activity of the whales.” Kastelein et al. (2006a) describe the response of harbor porpoise to an experimental acoustic alarm (discussed below; power averaged source level of 145 dB), while also noting that a striped dolphin showed no reaction to the alarm, despite both species being able to clearly detect the signal.

Second, unlike the studies discussed above which relate to echosounders, many of the cited studies do not present a relevant comparison. These studies discuss sources that are not appropriately or easily compared to the sources considered here and/or address responses of animals in experimental environments that are not appropriately compared to the likely exposure context here. For example, aside from the well-developed literature concerning “acoustic harassment” or “acoustic deterrent” devices—which are obviously designed for the express purpose of harassing marine mammals (usually specific species or groups)—Kastelein et al. (2006b) describe harbor seal responses to signals used as part of an underwater data communication network. In this case, seals in a pool were exposed to signals of relatively long duration (1-2 seconds) and high duty cycle for 15 minutes, with experimental signals of continuously varying frequency, three different sound blocks, or frequency sweeps. These seals swam away from the sound (though they did not attempt to reduce exposure by putting their heads out of the water), but this result is of questionable relevance to understanding the likely response of seals in the wild that may be exposed to a 1-ms single-frequency signal from an echosounder moving past the seal as a transient stimulus.

Some studies do not provide a relevant comparison not only because of differences in the source, but because they address sources (in some cases multiple sources) that are stationary (for extended periods of time in some cases), whereas AFSC surveys are infrequent and transient in any given location. Morton (2000) presents only brief speculation that an observed decline in abundance of Pacific white-sided dolphin coincided with introduction of 194-dB (source level) acoustic deterrent devices—an observation that is not relevant to consideration of a single mobile source that would be transient in space and time relevant to a receiver. Morton and Symonds (2002) similarly address displacement from a specific area due to a profusion of “high-powered” deterrent devices (the same 194-dB system discussed briefly in Morton (2000)) placed in restricted passages for extended time periods (6 years).

Third, the Commission relies heavily on the use of examples pertaining to the most sensitive species, which does not support an argument that the 120-dB threshold should be applied to all species. NMFS has acknowledged that the scientific evidence indicates that certain species are, in general, more acoustically sensitive than others. In particular, harbor porpoise and beaked whales are considered to be behaviorally sensitive, and it may be appropriate to consider use of lower behavioral harassment thresholds for these species. NMFS is considering this issue in its current work of developing new guidelines for assessing behavioral harassment; however, until this work is completed and new guidelines are identified (if appropriate), the existing generic thresholds are retained. Moreover, as is discussed above for other reasons, the majority of examples cited by the Commission are of limited relevance in terms of comparison of sound sources. In support of their statement that numerous researchers have observed marine mammals responding to sound from sources claimed to be similar to those considered herein, the Commission indeed cites numerous studies; however, the vast majority of these address responses of harbor porpoise or beaked whales to various types of acoustic alarms or deterrent devices.

We acknowledge that the Commission presents legitimate points in support of defining a threshold specific to non-impulsive, intermittent sources and that, among the large number of cited studies, there are a few that show relevant results of individual animals responding to exposure at lower received levels in ways that could be considered harassment. As noted in a previous comment response, NMFS is currently engaged in an ongoing effort towards developing updated guidance regarding the effects of anthropogenic sound on marine mammal behavior. However, prior to conclusion of this effort, NMFS will continue using the historical Level B harassment thresholds (or derivations thereof) and will appropriately evaluate behavioral harassment due to intermittent sound sources relative to the 160-dB threshold.

Comment 3: The Commission notes that NMFS has delineated two categories of acoustic sources, largely based on frequency, with those sources operating at frequencies greater than the known hearing ranges of any marine mammal (i.e., >180 kilohertz (kHz)) lacking the potential to disturb marine mammals by causing disruption of behavioral patterns. The Commission describes the recent scientific literature on acoustic sources with frequencies above 180 kHz (i.e., Deng et al., 2014; Hastie et al., 2014) and recommends that we estimate numbers of takes associated with those acoustic sources (or similar acoustic sources) with frequencies above 180 kHz that have been shown to elicit behavioral responses above the 120-dB threshold.

Response: As the Commission acknowledges, we considered the cited information in our Notice of Proposed Rulemaking. NMFS's response regarding the appropriateness of the 120-dB versus 160-dB rms thresholds was provided above in the response to Comment #2. In general, the referenced literature indicates only that sub-harmonics could be detectable by certain species at distances up to several hundred meters. As we have noted in previous responses, behavioral response to a stimulus does not necessarily indicate that Level B harassment, as defined by the MMPA, has occurred. Source levels of the secondary peaks considered in these studies—those within the hearing range of some marine mammals—mean that these sub-harmonics would either be below the threshold for behavioral harassment or would attenuate to such a level within a few meters. Beyond these important study details, these high-frequency (i.e., Category 1) sources and any energy they may produce below the primary frequency that could be audible to marine mammals would be dominated by a few primary sources (e.g., EK60) that are operated near-continuously—much like other Category 2 sources considered in our assessment of potential incidental take from AFSC's use of active acoustic sources—and the potential range above threshold would be so small as to essentially discount them. Further, recent sound source verification testing of these and other similar systems did not observe any sub-harmonics in any of the systems tested under controlled conditions (Crocker and Fratantonio, 2016). While this can occur during actual operations, the phenomenon may be the result of issues with the system or its installation on a vessel rather than an issue that is inherent to the output of the system. There is no evidence to suggest that Level B harassment of marine mammals should be expected in relation to use of active acoustic sources at frequencies exceeding 180 kHz.

Comment 4: ECO-SCI appears to suggest that we failed to use the best scientific evidence available in developing our proposed rulemaking and in making our preliminary determinations under the MMPA.

Response: As explained in detail in our Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (August 1, 2018; 83 FR 37638), NMFS did use the best scientific evidence available. In cases where population abundance estimates are not presented in NMFS' Stock Assessment Reports, either due to lack of available data or because the available data are considered outdated, we carefully described the data that are available, how those data support our assessment of the size and health of affected populations, and the process by which we evaluated the effects of the specified activity on the affected marine mammal species and stocks. The ECO-SCI comment letter evidences a limited understanding of the available data and confusion regarding relevant statutory and regulatory processes; and, ultimately, the commenter's apparent claims are not supported.

Description of Marine Mammals in the Area of the Specified Activity

We have reviewed AFSC's species descriptions—which summarize available information regarding status and trends, distribution and habitat preferences, behavior and life history, and auditory capabilities of the potentially affected species—for accuracy and completeness and refer the reader to Sections 3 and 4 of AFSC's application (and Sections 3 and 4 of Appendix C, which specifically addresses the IPHC activities), instead of reprinting the information here. Additional information regarding population trends and threats may be found in NMFS's Stock Assessment Reports (SAR; www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/marine-mammal-protection/marine-mammal-stock-assessments) and more general information about these species (e.g., physical and behavioral descriptions) may be found on NMFS's website (www.fisheries.noaa.gov/find-species).

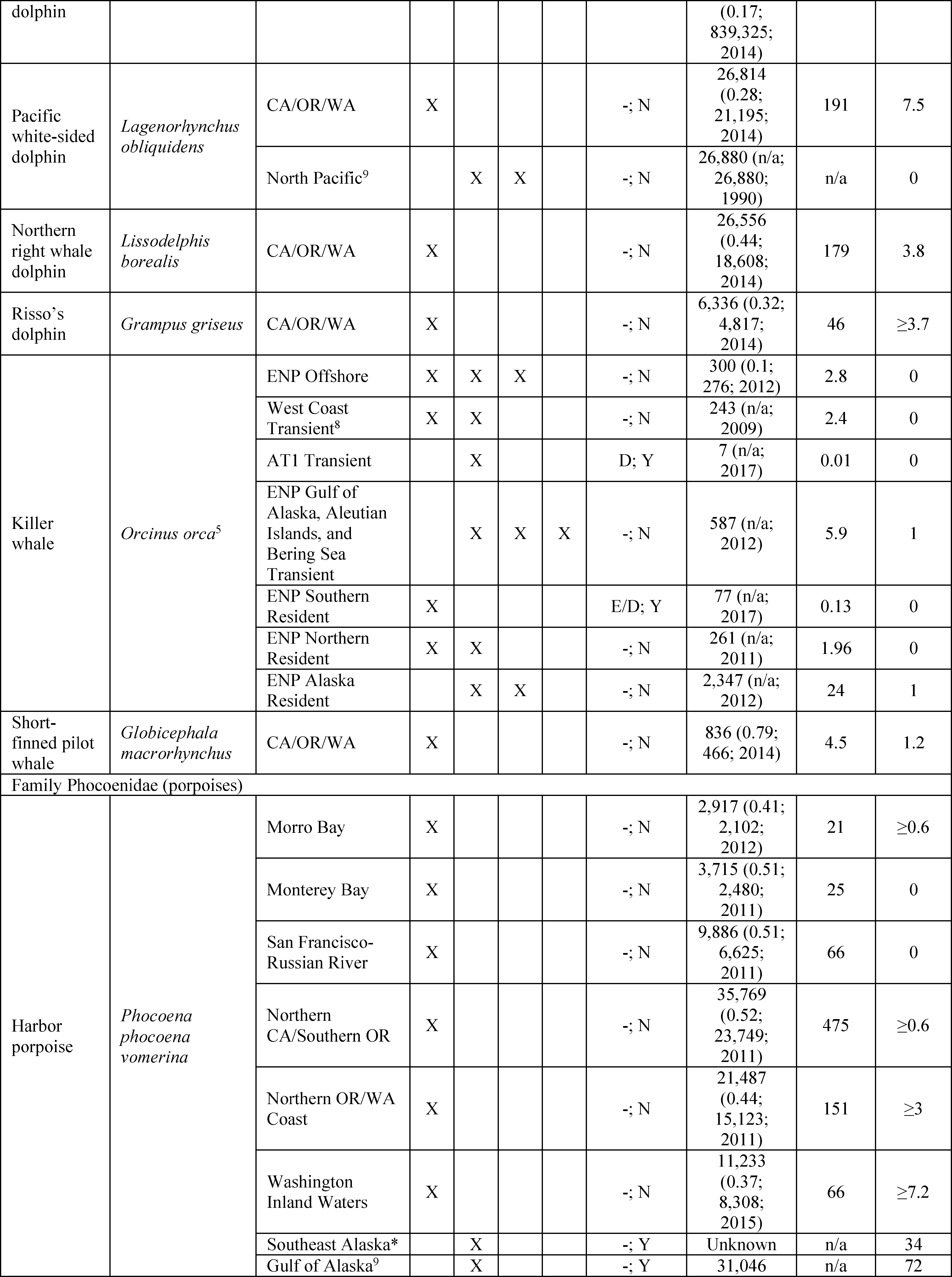

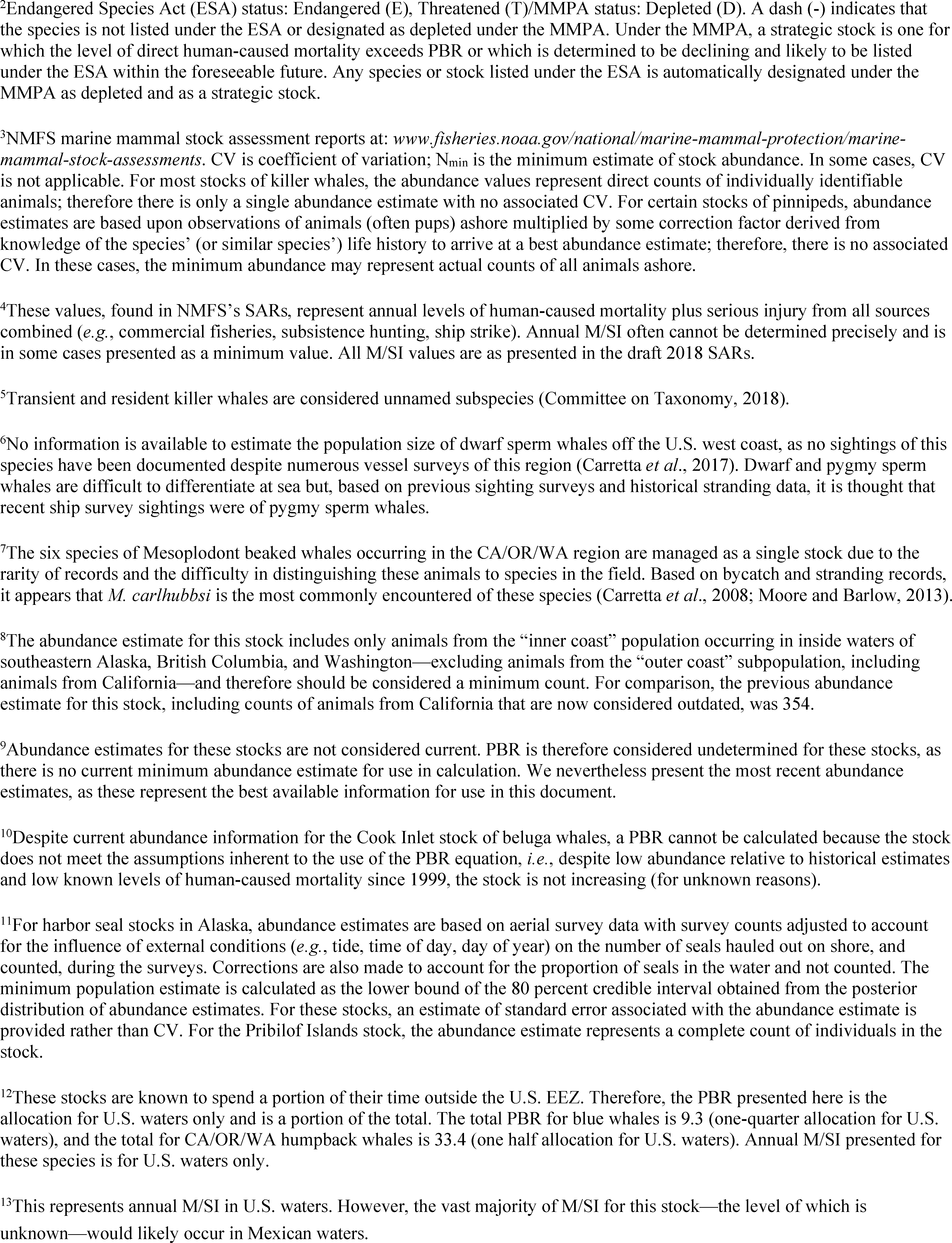

Table 1 lists all species with expected potential for occurrence in the specified geographical regions where AFSC and IPHC plan to conduct the specified activities and summarizes information related to the population or stock, including regulatory status under the MMPA and ESA and potential biological removal (PBR), where known. For taxonomy, we follow Committee on Taxonomy (2018). PBR, defined by the MMPA as the maximum number of animals, not including natural mortalities, that may be removed from a marine mammal stock while allowing that stock to reach or maintain its optimum sustainable population, is discussed in greater detail later in this document (see “Negligible Impact Analysis”).

Marine mammal abundance estimates presented in this document represent the total number of individuals that make up a given stock or the total number estimated within a particular study or survey area. NMFS's stock abundance estimates for most species represent the total estimate of individuals within the geographic area, if known, that comprises that stock. For some species, this geographic area may extend beyond U.S. waters. All managed stocks in the specified geographical regions are assessed in either NMFS's U.S. Alaska SARs or U.S. Pacific SARs. All values presented in Table 1 are the most recent available at the time of writing and are available in the 2017 SARs (Carretta et al., 2018; Muto et al., 2018) or draft 2018 SARs (available online at: www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/marine-mammal-protection/draft-marine-mammal-stock-assessment-reports).

Forty species (with 88 managed stocks) are considered to have the potential to co-occur with AFSC and IPHC activities. Species that could potentially occur in the research areas but are not expected to have the potential for interaction with AFSC research gear or that are not likely to be harassed by AFSC's use of active acoustic devices are described briefly but omitted from further analysis. These include extralimital species, which are species that do not normally occur in a given area but for which there are one or more occurrence records that are considered beyond the normal range of the species. Species considered to be extralimital here are the narwhal (Monodon monoceros; CSBSRA only), Bryde's whale (Balaenoptera edeni brydei; IPHC U.S. west coast research area only), and the Western North Pacific stock of the gray whale (see our Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (August 1, 2018; 83 FR 37638) for additional discussion of the gray whale). In addition, the sea otter is found in coastal waters—with the northern (or eastern) sea otter (Enhydra lutris kenyoni) found in Alaska—and the Pacific walrus (Odobenus rosmarus divergens) and polar bear (Ursus maritimus) may also occur in AFSC research areas. However, these species are managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and are not considered further in this document.

Additional detail regarding the affected species and stocks was provided in our Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (August 1, 2018; 83 FR 37638) and is not repeated here.

Take Reduction Planning—Take reduction plans are designed to help recover and prevent the depletion of strategic marine mammal stocks that interact with certain U.S. commercial fisheries, as required by Section 118 of the MMPA. The immediate goal of a take reduction plan is to reduce, within six months of its implementation, the M/SI of marine mammals incidental to commercial fishing to less than the PBR level. The long-term goal is to reduce, within five years of its implementation, the M/SI of marine mammals incidental to commercial fishing to insignificant levels, approaching a zero serious injury and mortality rate, taking into account the economics of the fishery, the availability of existing technology, and existing state or regional fishery management plans. Take reduction teams are convened to develop these plans.

There are no take reduction plans currently in effect for Alaskan fisheries. For marine mammals off the U.S. west coast, there is currently one take reduction plan in effect (Pacific Offshore Cetacean Take Reduction Plan). The goal of this plan is to reduce M/SI of several marine mammal stocks incidental to the California thresher shark/swordfish drift gillnet fishery (CA DGN). A team was convened in 1996 and a final plan produced in 1997 (62 FR 51805; October 3, 1997). Marine mammal stocks of concern initially included the California, Oregon, and Washington stocks for beaked whales, short-finned pilot whales, pygmy sperm whales, sperm whales, and humpback whales. The most recent five-year averages of M/SI for these stocks are below PBR. More information is available online at: www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/marine-mammal-protection/pacific-offshore-cetacean-take-reduction-plan. Of the stocks of concern, the AFSC requested the authorization of incidental M/SI for the short-finned pilot whale only (on behalf of IPHC; see “Estimated Take” later in this document). The most recent reported average annual human-caused mortality for short-finned pilot whales (2010-14) is 1.2 animals. The IPHC does not use drift gillnets in its fisheries research program; therefore, take reduction measures applicable to the CA DGN fisheries are not relevant.

Unusual Mortality Events (UME)—A UME is defined under the MMPA as a stranding that is unexpected; involves a significant die-off of any marine mammal population; and demands immediate response. From 1991 to the present, there have been 19 formally recognized UMEs on the U.S. west coast or in Alaska involving species under NMFS' jurisdiction. The only currently ongoing investigations involve Guadalupe fur seals and California sea lions along the west coast. Increased strandings of Guadalupe fur seals (up to eight times the historical average) have occurred along the entire coast of California. These increased strandings were reported beginning in January 2015 and peaked from April through June 2015, but have remained well above average through 2018. Findings from the majority of stranded animals include malnutrition with secondary bacterial and parasitic infections. Beginning in January 2013, elevated strandings of California sea lion pups were observed in southern California, with live sea lion strandings nearly three times higher than the historical average. Findings to date indicate that a likely contributor to the large number of stranded, malnourished pups was a change in the availability of sea lion prey for nursing mothers, especially sardines. These UMEs are occurring in the same areas and the causes and mechanisms of this remain under investigation (www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/marine-life-distress/2015-2019-guadalupe-fur-seal-unusual-mortality-event-california; www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/marine-life-distress/2013-2017-california-sea-lion-unusual-mortality-event-california; accessed March 18, 2019).

Another recent, notable UME involved large whales and occurred in the western Gulf of Alaska and off of British Columbia, Canada. Beginning in May 2015, elevated large whale mortalities (primarily fin and humpback whales) occurred in the areas around Kodiak Island, Afognak Island, Chirikof Island, the Semidi Islands, and the southern shoreline of the Alaska Peninsula. Although most carcasses have been non-retrievable as they were discovered floating and in a state of moderate to severe decomposition, the UME is likely attributable to ecological factors, i.e., the 2015 El Niño, “warm water blob,” and the Pacific Coast domoic acid bloom. The dates of the UME are considered to be from May 22 through December 31, 2015 (western Gulf of Alaska) and from April 23, 2015, through April 16, 2016 (British Columbia). More information is available online at www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/marine-life-distress/2015-2016-large-whale-unusual-mortality-event-western-gulf-alaska.

Additional UMEs in the past ten years include those involving ringed, ribbon, spotted, and bearded seals (collectively “ice seals”) (2011; disease); harbor porpoises in California (2008; cause determined to be ecological factors); Guadalupe fur seals in the Northwest (2007; undetermined); large whales in California (2007; human interaction); cetaceans in California (2007; undetermined); and harbor porpoises in the Pacific Northwest (2006; undetermined). For more information on UMEs, please visit: www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/marine-mammal-protection/marine-mammal-unusual-mortality-events.

Marine Mammal Hearing

Hearing is the most important sensory modality for marine mammals underwater, and exposure to anthropogenic sound can have deleterious effects. To appropriately assess the potential effects of exposure to sound, it is necessary to understand the frequency ranges marine mammals are able to hear. Current data indicate that not all marine mammal species have equal hearing capabilities (e.g., Richardson et al., 1995; Wartzok and Ketten, 1999; Au and Hastings, 2008). To reflect this, Southall et al. (2007) recommended that marine mammals be divided into functional hearing groups based on directly measured or estimated hearing ranges on the basis of available behavioral response data, audiograms derived using auditory evoked potential techniques, anatomical modeling, and other data. Note that no direct measurements of hearing ability have been successfully completed for mysticetes (i.e., low-frequency cetaceans). Subsequently, NMFS (2016) described generalized hearing ranges for these marine mammal hearing groups. Generalized hearing ranges were chosen based on the approximately 65 dB threshold from the normalized composite audiograms, with an exception for lower limits for low-frequency cetaceans where the result was deemed to be biologically implausible and the lower bound from Southall et al. (2007) retained. The functional groups and the associated frequencies are indicated below (note that these frequency ranges correspond to the range for the composite group, with the entire range not necessarily reflecting the capabilities of every species within that group):

- Low-frequency cetaceans (mysticetes): Generalized hearing is estimated to occur between approximately 7 Hz and 35 kHz, with best hearing estimated to be from 100 Hz to 8 kHz;

- Mid-frequency cetaceans (larger toothed whales, beaked whales, and most delphinids): Generalized hearing is estimated to occur between approximately 150 Hz and 160 kHz, with best hearing from 10 to less than 100 kHz;

- High-frequency cetaceans (porpoises, river dolphins, and members of the genera Kogia and Cephalorhynchus; including two members of the genus Lagenorhynchus, on the basis of recent echolocation data and genetic data): Generalized hearing is estimated to occur between approximately 275 Hz and 160 kHz;

- Pinnipeds in water; Phocidae (true seals): Functional hearing is estimated to occur between approximately 50 Hz to 86 kHz, with best hearing between 1-50 kHz;

- Pinnipeds in water; Otariidae (eared seals): Functional hearing is estimated to occur between 60 Hz and 39 kHz for Otariidae, with best hearing between 2-48 kHz.

For more detail concerning these groups and associated frequency ranges, please see NMFS (2018) for a review of available information. Forty marine mammal species (30 cetacean and ten pinniped (four otariid and six phocid) species) have the potential to co-occur with AFSC and IPHC research activities. Please refer to Table 1. Of the 30 cetacean species that may be present, eight are classified as low-frequency cetaceans (i.e., all mysticete species), eighteen are classified as mid-frequency cetaceans (i.e., all delphinid and ziphiid species and the sperm whale), and four are classified as high-frequency cetaceans (i.e., porpoises and Kogia spp.).

Potential Effects of the Specified Activity on Marine Mammals and Their Habitat

We provided discussion of the potential effects of the specified activity on marine mammals and their habitat in our Federal Register Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (August 1, 2018; 83 FR 37638). Therefore, we do not reprint the information here but refer the reader to that document. That document included a summary and discussion of the ways that components of the specified activity may impact marine mammals and their habitat. The “Estimated Take” section later in this document includes a quantitative analysis of the number of individuals that are expected to be taken by this activity. The “Negligible Impact Analysis and Determination” section considers the content of this section and the material it references, the “Estimated Take” section, and the “Mitigation” section, to draw conclusions regarding the likely impacts of these activities on the reproductive success or survivorship of individuals and how those impacts on individuals are likely to impact marine mammal species or stocks.

Estimated Take

This section provides an estimate of the number of incidental takes proposed for authorization, which will inform both NMFS's consideration of whether the number of takes is “small” and the negligible impact determination.

Except with respect to certain activities not pertinent here, section 3(18) of the MMPA defines “harassment” as any act of pursuit, torment, or annoyance which (i) has the potential to injure a marine mammal or marine mammal stock in the wild (Level A harassment); or (ii) has the potential to disturb a marine mammal or marine mammal stock in the wild by causing disruption of behavioral patterns, including, but not limited to, migration, breathing, nursing, breeding, feeding, or sheltering (Level B harassment).

Take of marine mammals incidental to AFSC research activities could occur as a result of (1) injury or mortality due to gear interaction (Level A harassment, serious injury, or mortality); (2) behavioral disturbance resulting from the use of active acoustic sources (Level B harassment only); or (3) behavioral disturbance of pinnipeds resulting from incidental approach of researchers (Level B harassment only). Below we describe how the potential take is estimated.

Estimated Take Due to Gear Interaction

In order to estimate the number of potential incidents of take that could occur through gear interaction, we first consider AFSC's and IPHC's record of past such incidents, and then consider in addition other species that may have similar vulnerabilities to AFSC trawl and IPHC longline gear as those species for which we have historical interaction records. Historical interactions with research gear are described in Table 2, and we anticipate that all species that interacted with AFSC or IPHC fisheries research gear historically could potentially be taken in the future. Available records are for the years 2004 through present (AFSC) and 1998 through present (IPHC). All historical AFSC interactions have taken place in the GOARA, and have occurred during use of either the Cantrawl surface trawl net or with a bottom trawl. Historical IPHC interactions have occurred during use of bottom longlines and were located in the GOARA (southeast Alaska) or west coast (offshore Oregon). AFSC has no historical interactions for any longline or gillnet gear, and there are no historical interactions in the BSAIRA or CSBSRA. Please see Figures 6-1 and C-6 in the AFSC request for authorization for specific locations of these incidents.

| Gear | Survey | Date | Location 1 | Species | Number killed | Number released alive | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bottom longline | IPHC setline | 7/17/1999 | West coast | Harbor seal | 1 | 1 | |

| Bottom longline | IPHC setline | 7/23/2003 | SE Alaska | Steller sea lion | 1 | 1 | |

| Bottom longline | IPHC setline | 7/16/2007 | SE Alaska | Steller sea lion | 1 | 1 | |

| Bottom trawl | Gulf of Alaska Biennial Shelf and Slope Bottom Trawl Groundfish Survey | 6/13/2009 | GOARA | Northern fur seal 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Bottom longline | IPHC setline | 7/31/2011 | West coast | Harbor seal | 1 | 1 | |

| Surface trawl (Cantrawl) | Gulf of Alaska Assessment | 9/10/2011 | GOARA | Dall's porpoise | 1 | 1 | |

| Surface trawl (Cantrawl) | Gulf of Alaska Assessment | 9/21/2011 | GOARA | Dall's porpoise | 1 | 1 | |

| Bottom trawl | ADFG Large Mesh Trawl Survey | 9/5/2014 | GOARA | Harbor seal | 1 | 1 | |

| Bottom longline | IPHC setline | 7/22/2016 | SE Alaska | Steller sea lion | 1 | 1 | |

| Bottom longline | Longline Stock Assessment Survey | 8/18/2019 | GOARA | Steller sea lion | 1 | 1 | |

| Total individuals captured | Northern fur seal | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Dall's porpoise | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Harbor seal | 3 | 3 | |||||

| Steller sea lion | 4 | 4 | |||||

| 1 AFSC interactions are described by research area. IPHC research programs are not distributed according to AFSC research areas and so are described by geographic location. Specific locations of all interactions are shown in Figures 6-1 and C-6 of the application. | |||||||

| 2 Based on the location of this incident, the captured animal was believed to be from the eastern Pacific stock of northern fur seal. | |||||||

In order to use these historical interaction records as the basis for the take estimation process, and because we have no specific information to indicate whether any given future interaction might result in M/SI versus Level A harassment, we conservatively assume that all interactions equate to mortality for these fishing gear interactions. AFSC and IPHC have historically had only infrequent interactions with marine mammals, e.g., from 2004-2015 AFSC conducted at least 1,250 trawl tows per year, with only three (a fourth occurred during a survey conducted by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game) marine mammal interactions (Table 2). However, we assume that any of the historically-captured species (northern fur seal, Dall's porpoise, harbor seal, Steller sea lion) could be captured in any year.

We consider all of the interaction records available to us. In consideration of these data, we assume that one individual of each of the historically-captured species (Table 2) could be captured per year over the course of the five-year period of validity for these regulations, specific to relevant survey operations where the species occur (e.g., one harbor seal taken per year specific to IPHC longline survey operations, one Dall's porpoise taken per year specific to AFSC trawl survey operations in GOARA, one Dall's porpoise taken per year specific to AFSC trawl survey operations in BSAIRA). Table 3 shows the projected five-year total captures of the historically-captured species for this rule, as described above, for AFSC trawl gear and IPHC longline gear only. Although more than one individual Dall's porpoise has been captured in a single year, interactions have historically occurred only infrequently. Therefore, we believe that the above assumption appropriately reflects the likely total number of individuals involved in research gear interactions over a five-year period and that the assumption is precautionary in that it separately accounts for potential vulnerability of species to gear interaction in the different research areas. Harbor seals are expected to have less frequency of interaction than the fur seal or Steller sea lion due to their more inshore and coastal distribution. AFSC requested authorization of one take per harbor seal stock in each relevant research area over the 5-year period (note that these takes are not included in Table 3 but are incorporated in Table 5). These estimates are based on the assumption that annual effort (e.g., total annual trawl tow time) over the five-year authorization period will be approximately equivalent to the annual effort during prior years for which we have interaction records.

| Gear | Species | AFSC GOARA average annual take (total) | AFSC BSAIRA average annual take (total) | IPHC average annual take (total) 2 | Projected 5-year total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trawl | Northern fur seal 3 | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 10 | |

| Dall's porpoise | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 10 | ||

| Longline | Harbor seal | 1 (5) | 5 | ||

| Steller sea lion 4 | 1 (5) | 5 | |||

| 1 Projected takes based on species interaction records in analogous commercial fisheries (versus historical records) are incorporated in Table 5 below, as are all projected takes within the CSBSRA. | |||||

| 2 IPHC activities are not defined by the three AFSC research areas and may occur anywhere within the IPHC research areas off the U.S. west coast or in the Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea. Projected IPHC harbor seal takes could occur to any stock of harbor seal. Historical IPHC takes of Steller sea lion have been of the eastern DPS (based on geographic location), but potential future takes could occur to either eastern or western DPS. | |||||

| 3 Referring to expected potential future takes of eastern Pacific stock northern fur seals in AFSC trawl gear on basis of historical record. Additional take of California stock northern fur seals, inferred based on vulnerability and geographic overlap, are incorporated in Table 5 below. | |||||

| 4 Immediately prior to publication of this final rule, a Steller sea lion take occurred in AFSC longline operations in the GOARA (Table 2). However, this incident does not affect our overall evaluation of the likelihood for Steller sea lion take due to AFSC longline operations, and we retain the analytical structure discussed herein. | |||||

As background to the process of determining which species not historically taken may have sufficient vulnerability to capture in AFSC gear to justify inclusion in the take authorization request (or whether species historically taken may have vulnerability to gears in which they have not historically been taken or additional vulnerability not reflected above due to activity in other areas such as the CSBSRA), we note that the AFSC is NMFS' research arm in Alaska and may be considered as a leading source of expert knowledge regarding marine mammals (e.g., behavior, abundance, density) in the areas where they operate. The species for which the take request was formulated were selected by the AFSC, and we have concurred with these decisions. We also note that, in addition to consulting NMFS's List of Fisheries (LOF; described below), the historical interaction records described above for the IPHC informed our consideration of risk of interaction due to AFSC's use of longline gear (for which there are no historical interaction records).

In order to estimate the total potential number of incidents of takes that could occur incidental to the AFSC's use of trawl, longline, and gillnet gear, and IPHC's use of longline gear, over the five-year period of validity for these regulations (i.e., takes additional to those described in Table 3), we first consider whether there are additional species that may have similar vulnerability to capture in trawl or longline gear as the five species described above that have been taken historically and then evaluate the potential vulnerability of these and other species to additional gears.

We believe that the Pacific white-sided dolphin likely has similar vulnerability to capture in trawl gear as the Dall's porpoise, given similar habitat preferences and with documented vulnerability to capture in both commercial and research trawls. The harbor porpoise is also considered vulnerable to capture in trawl gear, but likely with less frequency of interaction given its inshore and coastal distribution. The Steller sea lion is considered to have similar vulnerability to capture in trawl gear as the northern fur seal, given similar habitat preferences and with documented vulnerability to capture in commercial trawls. In addition to the one northern fur seal per year from the eastern Pacific stock that could be captured in each relevant research area (Table 3), we assume that one additional northern fur seal from the California stock could be taken in trawl gear over the 5-year period. The assumed lesser frequency of interaction is due to presumed lower occurrence of California stock fur seals in AFSC research areas. Only approximately half of this relatively small stock of fur seals ranges to the eastern GOARA. Similar to the harbor porpoise, spotted seals are expected to have similar vulnerability to capture in trawl gear as historically captured pinnipeds, but with less frequency of interaction due to its more inshore and coastal distribution. AFSC requested authorization of one take of spotted seal in each relevant research area over the 5-year period. This assumption is supported by LOF records (Table 5).

Historical IPHC take records also illustrate likely similar vulnerabilities to capture by AFSC longline gear (as demonstrated by a recent take by AFSC longline gear in the GOARA; Table 2). However, due to reduced use of longline gear by AFSC relative to IPHC activity, we expect that one Steller sea lion from each DPS could be taken over the 5-year period in each relevant research area. Despite IPHC records of harbor seal capture in longline gear, we do not believe that AFSC use of longline gear presents similar risk, in part due to the relative infrequency of use but also because of a lack of expected geographic overlap between AFSC longline sets and harbor seal occurrence. IPHC conducts many more longline sets per year but also conducts survey effort further inshore than does AFSC (water depths of 18 m). No take of harbor seals incidental to AFSC longline survey effort is authorized. Northern fur seals and California sea lions are considered analogous to Steller sea lions due to similar vulnerability to capture in longline gear. AFSC has requested authorization of one take over the 5-year period for each fur seal stock in each research area where fur seals are found and, on behalf of IPHC, requested authorization of one fur seal per year (which could be from either stock) and one California sea lion over the 5-year period. Finally, the spotted seal may have similar vulnerability to interaction with longline gear as the harbor seal, but likely with less frequency given the limited overlap between the species range and survey effort. We authorize one take over the 5-year period for IPHC survey effort, but none for AFSC given very little expected overlap. These assumptions are supported by LOF records (Table 5).

In order to evaluate the potential vulnerability of additional species to trawl and longline and of all species to gillnet gear, we first consulted the LOF, which classifies U.S. commercial fisheries into one of three categories according to the level of incidental marine mammal M/SI that is known to occur on an annual basis over the most recent five-year period (generally) for which data has been analyzed: Category I, frequent incidental M/SI; Category II, occasional incidental M/SI; and Category III, remote likelihood of or no known incidental M/SI. We provide summary information, as presented in the 2018 LOF (83 FR 5349; February 7, 2018), in Table 4. In order to simplify information presented, and to encompass information related to other similar species from different locations, we group marine mammals by genus (where there is more than one member of the genus found in U.S. waters). Where there are documented incidents of M/SI incidental to relevant commercial fisheries, we note whether we believe those incidents provide sufficient basis upon which to infer vulnerability to capture in AFSC or IPHC research gear. For a listing of all Category I, II, and II fisheries using relevant gears, associated estimates of fishery participants, and specific locations and fisheries associated with the historical fisheries takes indicated in Table 4 below, please see the 2018 LOF. For specific numbers of marine mammal takes associated with these fisheries, please see the relevant SARs. More information is available online at www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/marine-mammal-protection/marine-mammal-protection-act-list-fisheries and www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/marine-mammal-protection/marine-mammal-stock-assessments.

| Species 1 | Trawl 2 | Vulnerability inferred? | Longline 2 | Vulnerability inferred? | Gillnet 2 | Vulnerability inferred? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Pacific right whale | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Bowhead whale | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Gray whale | Y | N | N | N | Y | N |

| Humpback whale | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N |

| Balaenoptera spp | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N |

| Sperm whale | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Kogia spp | n/a | n/a | Y | N | n/a | n/a |

| Cuvier's beaked whale | N | N | Y | N | N | N |

| Baird's beaked whale | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Mesoplodon spp | N | N | Y | N | N | N |

| Beluga whale | N | Y | N | N | Y | N |

| Common bottlenose dolphin | n/a | n/a | Y | Y | n/a | n/a |

| Stenella spp | n/a | n/a | Y | N | n/a | n/a |

| Delphinus spp | n/a | n/a | Y | Y | n/a | n/a |

| Lagenorhynchus spp | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y |

| Northern right whale dolphin | n/a | n/a | N | N | n/a | n/a |

| Risso's dolphin | n/a | n/a | Y | Y | n/a | n/a |

| Killer whale | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N |

| Globicephala spp | n/a | n/a | Y | Y | n/a | n/a |

| Harbor porpoise | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Dall's porpoise 3 | n/a | n/a | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Guadalupe fur seal 4 | n/a | n/a | N | N | n/a | n/a |

| Northern fur seal 3 | n/a | n/a | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| California sea lion 5 | n/a | n/a | Y | Y | n/a | n/a |

| Steller sea lion 3 | Y | Y | n/a | n/a | Y | Y |

| Bearded seal | Y | Y | N | N | N | N |

| Phoca spp 3 | Y | Y | n/a | n/a | Y | Y |

| Ringed seal | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| Ribbon seal | Y | Y | N | N | N | N |

| Northern elephant seal | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N |

| 1 Please refer to Table 1 for taxonomic reference. | ||||||

| 2 Indicates whether any member of the genus has documented incidental M/SI in a U.S. fishery using that gear in the most recent five-year timespan for which data is available. For those species not expected to occur in Alaskan waters, trawl and gillnet gear are not applicable (these gears would only be used in Alaskan waters). | ||||||

| 3 This exercise is considered “not applicable” for those species historically captured by AFSC or IPHC gear. Historical record, rather than analogy, is considered the best information upon which to base a take estimate. | ||||||

| 4 It is likely that Guadalupe fur seals are taken in Mexican fisheries, but there are no available records. | ||||||

| 5 There are no records of take for California sea lions in commercial longline fisheries, but there have been multiple takes of California sea lions in longline surveys conducted by NMFS's Southwest Fisheries Science Center. We therefore infer vulnerability for the species to research longline gear. | ||||||

Information related to incidental M/SI in relevant commercial fisheries is not, however, the sole determinant of whether it may be appropriate to authorize take incidental to AFSC survey operations. A number of factors (e.g., species-specific knowledge regarding animal behavior, overall abundance in the geographic region, density relative to AFSC survey effort, feeding ecology, propensity to travel in groups commonly associated with other species historically taken) were taken into account by the AFSC to determine whether a species may have a similar vulnerability to certain types of gear as historically taken species. In some cases, we have determined that species without documented M/SI may nevertheless be vulnerable to capture in AFSC research gear. Similarly, we have determined that some species groups with documented M/SI are not likely to be vulnerable to capture in AFSC gear. In these instances, we provide further explanation below. Those species with no records of historical interaction with AFSC research gear and no documented M/SI in relevant commercial fisheries, and for which the AFSC has not requested the authorization of incidental take, are not considered further in this section. The AFSC believes generally that any sex or age class of those species for which take authorization is requested could be captured.

In order to estimate a number of individuals that could potentially be captured in AFSC research gear for those species not historically captured, we first determine which species may have vulnerability to capture in a given gear. Of those species, we then determine whether any may have similar propensity to capture in a given gear as a historically captured species. For these species, we assume it is possible that take could occur while at the same time contending that, absent significant range shifts or changes in habitat usage, capture of a species not historically captured would likely be a very rare event. Therefore, we assume that capture would be a rare event such that authorization of a single take over the five-year period, for each region where the gear is used and the species is present, is likely sufficient to capture the risk of interaction.

Trawl—From the 2018 LOF, we infer vulnerability to trawl gear for the bearded seal, ringed seal, ribbon seal, and northern elephant seal. This is in addition to the species for which vulnerability is indicated by historical AFSC interactions (described above).

For the beluga whale, we believe that there is a reasonable likelihood of incidental take in trawl gear although there are no records of incidental M/SI in relevant commercial fisheries. Commercial fisheries using trawl gear have largely been absent from areas where beluga whales occur and, in particular, there are no commercial trawl fisheries in the CSBSRA. AFSC examined the potential for incidental take of beluga whales by evaluating the areas of overlap between their planned fisheries research activities and beluga whale distribution, considering the seasonality of both the research activities and the species distributions as well as other factors that may influence the degree of potential overlap such as sea and shorefast ice occurrence. In considering the possible take of beluga whales, the AFSC considered that beluga whales show behavior similar to large dolphins and porpoises. While no belugas have been taken in AFSC research or commercial trawl fisheries, there have been takes of large dolphins elsewhere in trawls. Beluga whales may occur in summer periods within the Chukchi and Beaufort Sea regions where the AFSC may be conducting trawl surveys. Thus, AFSC requested authorization of one take each from two stocks of beluga whale (eastern Chukchi stock and Beaufort Sea stock) in fisheries research trawl surveys over the 5-year authorization period. Potential spatiotemporal overlap between AFSC trawl survey activities and other beluga whale stocks was evaluated and determined to not support a take authorization request for other stocks of beluga whale.

It is also possible that a captured animal may not be able to be identified to species with certainty. Certain pinnipeds and small cetaceans are difficult to differentiate at sea, especially in low-light situations or when a quick release is necessary. For example, a captured delphinid that is struggling in the net may escape or be freed before positive identification is made. Therefore, the AFSC requested the authorization of incidental take for one unidentified pinniped and one unidentified small cetacean in trawl gear for each research area over the course of the five-year period of authorization. One exception is for small cetaceans in the CSBSRA, as no cetacean interactions with trawl gear are expected in that region (other than the aforementioned potential beluga whale interactions), as small cetaceans occur only rarely in this region.

Longline—The process is the same as is described above for trawl gear. From the 2018 LOF, we infer vulnerability to longline gear for the Dall's porpoise, Risso's dolphin, bottlenose dolphin, common dolphin, short-finned pilot whale, and ringed seal. This is in addition to the species for which vulnerability is indicated by historical AFSC interactions (described above).

Based on the 2018 LOF and historical observations of sperm whale and killer whale interactions with research longline gear, we also infer vulnerability to interaction with longline gear for killer whales (Alaska resident stock only) and sperm whales (North Pacific stock only). Although we generally believe that, despite records of interaction with analogous commercial fisheries, the potential for incidental take of any large whale (i.e., baleen whales or sperm whale), beaked whale, or killer whale in research gear is so unlikely as to be discountable, there is a long history of attempted depredation of longline gear by animals from these stocks in Alaska, with take of these species having occurred in commercial fisheries. Between 2010 and 2014, five sperm whales are recorded as having been seriously injured in the Gulf of Alaska sablefish longline fishery, while there have been two instances of killer whale M/SI in BSAI longline fisheries (Helker et al., 2016). Cetaceans have never been caught or entangled in AFSC or IPHC longline research gear. If interactions occur, marine mammals depredate hooked fish from the gear, but typically leave the hooks attached although occasionally bent or broken (i.e., evidence of the interaction). Certain species, particularly killer whales in the Bering Sea and sperm whales in the Gulf of Alaska, are commonly attracted to longline fishing operations and are adept at removing fish from longline gear as it is retrieved. Although we consider it unlikely that AFSC or IPHC research activities would result in any takes of either sperm whales or killer whales, AFSC requested the authorization of such take as a precautionary measure, given the observed interactions of these species with research longline gear. Since longline depredation by sperm whales is known to occur only in Alaskan waters, requested take is limited to the North Pacific stock. Commercial fishery takes have been reported for both transient and resident stocks of killer whale. However, the Alaska resident stock consumes fish (e.g., Herman et al., 2005) and is most likely to be involved in depredation of research catch. In contrast, transient killer whales feed on marine mammals and are less likely to interact with research longline gears, and the limited effort for AFSC and IPHC research surveys compared to commercial fisheries does not justify take authorization for transient whales.

Although there are LOF interaction records in longlines for stenellid dolphin species, the harbor porpoise, and the northern elephant seal, we do not authorize take of these species through use of longline. No take is anticipated for the striped dolphin or for the long-beaked stock of common dolphin and coastal stock of bottlenose dolphin because of their expected pelagic and southerly distributions (respectively) relative to expected IPHC survey effort. Harbor porpoise have only been recorded as taken in commercial fisheries through use of pelagic longline in the Atlantic Ocean; there are no records of incidental take of harbor porpoise in longline fisheries in Alaska or off the U.S. west coast. Similarly, the LOF indicates that elephant seal interaction occurred only in a Hawaiian pelagic longline fishery.

As described for trawl gear, it is also possible that a captured animal may not be able to be identified to species with certainty. Although we expect that cetaceans would likely be able to be identified when captured in longline gear, pinnipeds are considered more likely to escape before the animal may be identified. Therefore, the AFSC requested the authorization of incidental take for one unidentified pinniped for each relevant research area, in addition to one unidentified pinniped captured in IPHC surveys, over the course of the five-year period of authorization.

Gillnet—The process is the same as is described above for trawl gear. From the 2018 LOF, we infer vulnerability to gillnet gear for the Pacific white-sided dolphin, harbor porpoise, Dall's porpoise, harbor seal, northern fur seal, and Steller sea lion. Gillnets are used only in Prince William Sound and at Little Port Walter in southeast Alaska. Therefore, only one take is authorized for relevant stocks of the vulnerable species over the 5-year period. This includes both the eastern Pacific and California stocks of northern fur seal and the Prince William Sound and Sitka/Chatham Strait stocks of harbor seal. Although there are LOF interaction records in gillnets for the sperm whale, beluga whale, and the northern elephant seal, we do not expect these species to be present in areas where AFSC plans to use gillnet research gear and no take of these species through use of gillnet is authorized.

AFSC also expects that there may be an interaction resulting in escape of an unidentified cetacean in gillnet gear, and requested the authorization of incidental take for one unidentified cetacean over the course of the five-year period of authorization.