AGENCY:

Securities and Exchange Commission.

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

The Securities and Exchange Commission (“Commission”) is adopting a new rule under the Investment Company Act of 1940 (“Investment Company Act” or the “Act”) that will address valuation practices and the role of the board of directors with respect to the fair value of the investments of a registered investment company or business development company (“fund”). The rule will provide requirements for determining fair value in good faith for purposes of the Act. This determination will involve assessing and managing material risks associated with fair value determinations; selecting, applying, and testing fair value methodologies; and overseeing and evaluating any pricing services used. The rule will permit a fund's board of directors to designate certain parties to perform the fair value determinations, who will then carry out these functions for some or all of the fund's investments. This designation will be subject to board oversight and certain reporting and other requirements designed to facilitate the board's ability effectively to oversee this party's fair value determinations. The rule will include a specific provision related to the determination of the fair value of investments held by unit investment trusts, which do not have boards of directors. The rule will also define when market quotations are readily available under the Act. The Commission is also adopting a separate rule providing the recordkeeping requirements that will be associated with fair value determinations and is rescinding previously issued guidance on the role of the board of directors in determining fair value and the accounting and auditing of fund investments.

DATES:

Effective date: This rule is effective March 8, 2021. Compliance dates: The applicable compliance dates are discussed in section II.G of this rule.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Zeena Abdul-Rahman, Senior Counsel; Joel Cavanaugh, Senior Counsel; Bradley Gude, Senior Counsel; Thoreau A. Bartmann, Senior Special Counsel; or Brian McLaughlin Johnson, Assistant Director, at (202) 551-6792, Investment Company Regulation Office, Division of Investment Management; Kieran G. Brown, Senior Counsel, or David J. Marcinkus, Branch Chief, at (202) 551-6825 or IMOCC@sec.gov, Chief Counsel's Office, Division of Investment Management; Securities and Exchange Commission, 100 F Street NE, Washington, DC 20549-8549. Regarding accounting and auditing matters: Jenson Wayne or Alexis Cunningham, Assistant Chief Accountants at (202) 551-6918 or IM-CAO@sec.gov, Chief Accountant's Office, Division of Investment Management, Securities and Exchange Commission; or Jeffrey Nick or Natalie Martin, Professional Accounting Fellows, at (202) 551-5300 or OCA@sec.gov, Office of the Chief Accountant, Securities and Exchange Commission.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

The Commission is adopting 17 CFR 270.2a-5 (new rule 2a-5) and 17 CFR 270.31a-4 (new rule 31a-4) under the Investment Company Act.

Table of Contents

I. Introduction

II. Discussion

A. Fair Value as Determined in Good Faith Under Section 2(a)(41) of the Act

1. Periodically Assess and Manage Valuation Risks

2. Establish and Apply Fair Value Methodologies

3. Test Fair Value Methodologies for Appropriateness and Accuracy

4. Pricing Services

5. Fair Value Policies and Procedures

B. Performance of Fair Value Determinations

1. Board Oversight

2. Board Reporting

3. Specification of Functions

C. Recordkeeping

D. Readily Available Market Quotations

E. Rescission of Prior Commission Releases

F. Existing Commission Guidance, Staff No-Action Letters, and Other Staff Guidance

G. Transition Period

H. Other Matters

III. Economic Analysis

A. Introduction

B. Economic Baseline

1. Current Regulatory Framework

2. Current Practices

3. Affected Parties

C. General Economic Considerations

1. Investment Adviser Role in Fair Value Determinations

2. Board Considerations When Designating Fair Value Determinations

3. General Discussion of Benefits and Costs of Good Faith Determinations of Fair Value

D. Benefits and Costs

1. Fair Value as Determined in Good Faith Under Section 2(a)(41) of the Act

2. Performance of Fair Value Determinations

3. Recordkeeping

4. Readily Available Market Quotations

5. Rescission of Prior Commission Releases and Guidance

6. Cost Estimates

7. Other Cost Considerations and Comments on Costs

E. Effects on Efficiency, Competition, and Capital Formation

F. Reasonable Alternatives

1. Designation to Officers of Internally Managed Fund Not Permitted

2. Safe Harbor

3. Three-Tiered Approach

4. More Principles-Based Approach

5. Designation of the Performance of Fair Value Determinations to Service Providers Other Than Advisers, Officers, Trustees, or Depositors

6. Not Permit Boards To Designate a Valuation Designee

IV. Paperwork Reduction Act

A. Introduction

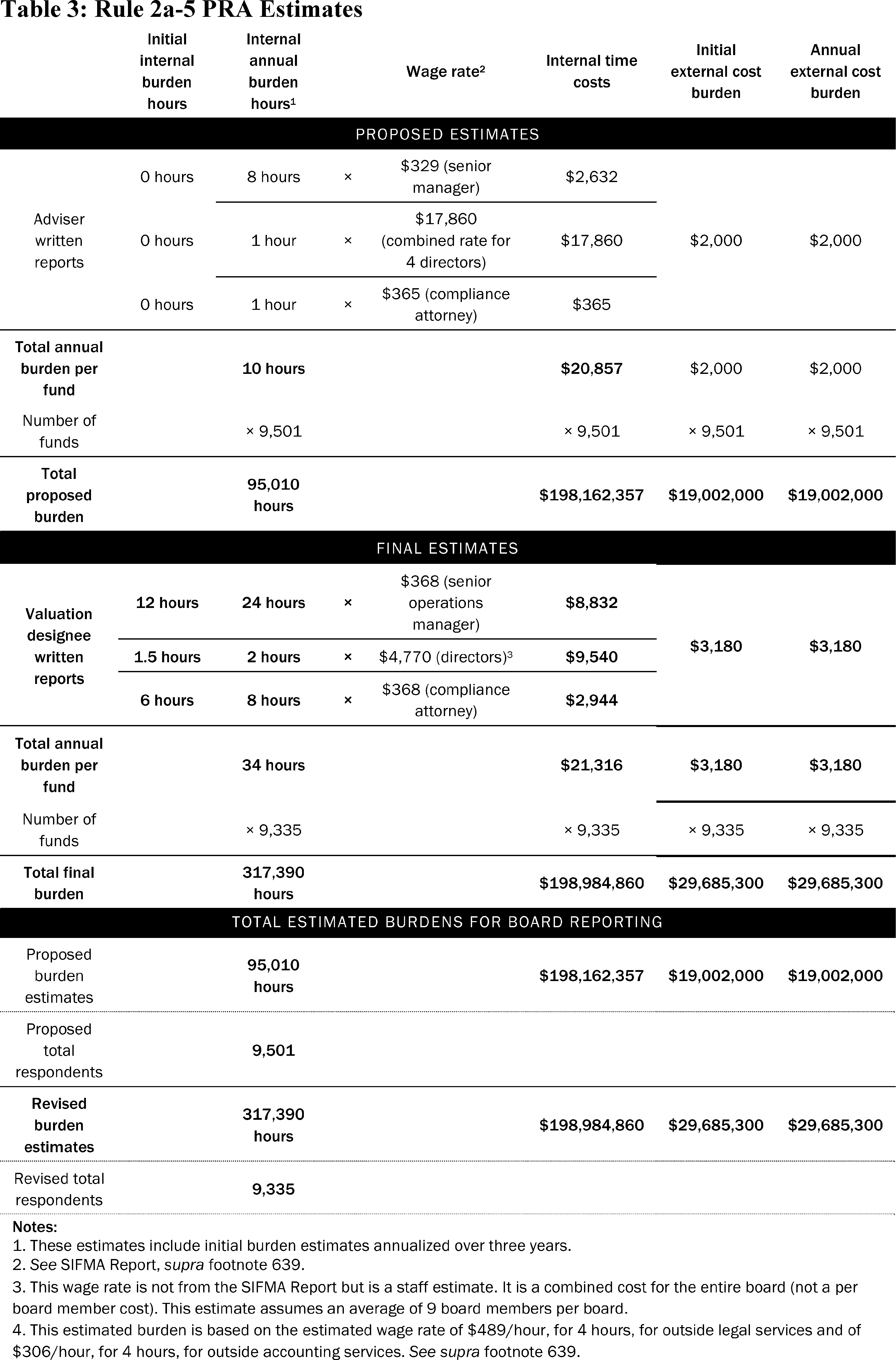

B. Rule 2a-5

C. Rule 31a-4

D. Rule 38a-1

V. Final Regulatory Flexibility Analysis

A. Need for the Rules

B. Significant Issues Raised by Public Comments

C. Small Entities Subject to the Rule

D. Projected Reporting, Recordkeeping, and Other Compliance Requirements

1. Recordkeeping

2. Board Reporting

E. Agency Action To Minimize Effect on Small Entities

VI. Update to Codification of Financial Reporting Policies Statutory Authority

I. Introduction

The Investment Company Act requires funds to value their portfolio investments using the market value of their portfolio securities when market quotations are “readily available,” and, when a market quotation for a portfolio security is not readily available or if the investment is not a security, by using the investment's fair value, as determined in good faith by the fund's board.[1] Proper valuation, among other things, promotes the purchase and sale of fund shares at fair prices, and helps to avoid dilution of shareholder interests.[2] Improper valuation can cause investors to pay fees that are too high or to base their investment decisions on inaccurate information.[3] We are adopting new 17 CFR 270.2a-5 (“rule 2a-5” or “final rule”) in response to the developments in markets and fund investment practices since the Commission last comprehensively addressed valuation 50 years ago. These include developments in the accounting and auditing literature,[4] the growing complexity of valuation, and intervening regulatory developments such as the development of ASC Topic 820 and the interplay of 17 CFR 270.38a-1 (“rule 38a-1” or “the compliance rule”) in facilitating board oversight of funds and the valuation process.[5] In addition, funds now invest in a greater variety of securities and other instruments, some of which did not exist in 1970 and may present different and more significant valuation challenges.[6] For example, funds that invest primarily in fixed income instruments (which may require fair value determinations for some or all of the portfolio assets) have expanded from around $800 billion in assets to over $4.5 trillion in just the last 20 years.[7]

We proposed rule 2a-5 in April 2020 and received more than 60 comment letters on the proposal.[8] Most commenters supported the Commission's goal of modernizing the regulatory framework for fund valuations.[9] Commenters generally agreed that the proposed framework for making a fair value determination was reasonable and consistent with current practice, but several requested additional flexibility regarding certain proposed requirements.[10]

We are adopting rule 2a-5 and companion 17 CFR 270.31a-4 (“rule 31a-4” and, together with rule 2a-5, the “rules”) with certain modifications from the proposal to address the comments we received, including targeted revisions to address issues noted with respect to certain of the more prescriptive elements of the proposed rule. We are also rescinding the Commission's previously issued guidance on the role of the board of directors in determining fair value and the accounting and auditing of fund investments as proposed and, in a change from the proposal, are superseding certain of the guidance on thinly traded securities and the use of pricing services the Commission issued in 2014.[11]

II. Discussion

The final rule provides requirements for determining fair value in good faith with respect to a fund for purposes of section 2(a)(41) of the Act and rule 2a-4 thereunder.[12] We believe that, in light of the developments discussed above and in the Proposing Release, to determine the fair value of fund investments in good faith requires a certain minimum, consistent framework for fair value and standard of baseline practices across funds, which the final rule establishes.[13]

Under the final rule, fair value as determined in good faith will require assessing and managing material risks associated with fair value determinations; selecting, applying, and testing fair value methodologies; and overseeing and evaluating any pricing services used. These required functions generally reflect our understanding of current practices used by funds to fair value their investments, and we discuss each in detail below.

The final rule also permits a fund's board [14] to designate a “valuation designee” to perform fair value determinations.[15] The valuation designee can be the adviser of the fund or, in a change from the proposal, an officer of an internally managed fund.[16] When a board designates the performance of determinations of fair value to a valuation designee for some or all of the fund's investments under the final rule, the final rule requires the board to oversee the valuation designee's performance of fair value determinations. To facilitate such oversight, the final rule also includes certain reporting and other requirements.[17] The final rule acknowledges that, consistent with longstanding practice, these valuation designees often play an important and valuable role in carrying out the day-to-day work of determining fair values. Under the final rule, the board remains responsible for the fair value determinations required by the statute. Where the board designates a valuation designee to perform fair value determinations under the final rule, the board will fulfill its continuing statutory obligations through active oversight of the valuation designee's performance of fair value determinations and compliance with the other requirements of the final rule.[18]

Also, as proposed, the final rule applies to all registered investment companies and BDCs, regardless of their classification or sub-classification (e.g., open-end funds and closed-end funds),[19] or their investment objectives or strategies (e.g., equity or fixed income; actively managed or tracking an index).[20] In the case of a unit investment trust (“UIT”), because a UIT does not have a board of directors or adviser, a UIT's trustee, or, in a change from the proposal, the UIT's depositor must conduct fair value determinations under the final rule.[21]

While many commenters thought that the proposal's general approach of balancing between prescriptive requirements and principles-based guidelines was reasonable, others requested modifications.[22] A number of commenters recommended that the Commission recast the proposed rule as a non-exclusive safe harbor or provide additional flexibility.[23] Some stated that they believed that fair value in good faith is a flexible concept, and thus they believed that fair value determinations are not amenable to a single approach, which they believed was consistent with the flexible approach taken in ASR 118.[24]

In light of the developments since the Commission last comprehensively addressed fair value determinations for funds, we believe that it is important to establish a minimum and consistent framework for fair value practices across funds. This framework also allows the Commission to articulate appropriate oversight measures, as outlined in section II.B below,[25] that are designed to help address valuation risks, including those arising from conflicts of interest.[26] The final rule establishes minimum and baseline standards that we believe are inherent in any good faith fair value determination, as informed by current industry practice. If we were to establish a safe harbor, in contrast, it may give the misleading impression that an approach to making fair value determinations that does not meet this minimum baseline would satisfy the board's statutory obligations.[27] The final rule does not establish a single approach to making such determinations. Instead, it establishes a principles-based framework for boards to use in creating their own specific process for making fair value determinations, including through designating and appropriately overseeing a valuation designee to perform certain valuation tasks.[28] It reflects an appropriate balance between providing a board or valuation designee with the flexibility to exercise judgment in the valuation process consistent with its good faith, paired with an appropriate set of baseline standards. Accordingly, we do not think that it is appropriate to recast rule 2a-5 as a safe harbor. However, we do agree with commenters that additional flexibility is appropriate in certain areas and have made a number of changes from the proposal in this regard, as discussed below.[29]

In support of a safe-harbor approach, some commenters raised concerns that violations of the proposed rule that may not directly impact the value given to an asset, for example a failure to keep records for the prescribed period, could raise doubts about whether a valuation was made consistent with the requirements of the Act. These commenters stated that this would be true even where the end result of the actual valuation was appropriate.[30] In response to these concerns, as discussed below, we are tailoring certain of the proposed reporting requirements and moving the proposed recordkeeping requirements out of rule 2a-5 and into a separate rule under the Act.[31] While a board or adviser's failure to comply with the final rule's requirements may call into question the effectiveness of the fund's fair value process and its compliance program, the Commission underscores that the objective of the final rule is to ensure that a fund's assets are properly valued. A violation of the final rule does not necessarily mean that the actual values ascribed to particular fund investments were in fact inappropriate, or, for example, that the fund has violated rule 22c-1.

A. Fair Value as Determined in Good Faith Under Section 2(a)(41) of the Act

Rule 2a-5 sets forth certain required functions that must be performed to determine the fair value of the fund's investments in good faith.[32] As discussed below, we are adopting these required functions substantially as proposed, with several changes from the proposal based on the comments the Commission received.

1. Periodically Assess and Manage Valuation Risks

We are adopting, as proposed, the requirement to assess periodically any material risks associated with the determination of the fair value of the fund's investments, including material conflicts of interest, and to manage those identified valuation risks.[33] Also as proposed, the final rule does not identify other specific valuation risks that may need to be addressed under this requirement or establish a specific re-assessment frequency.

Several commenters expressed general support for the valuation risk requirement,[34] with others suggesting certain modifications, particularly regarding whether the final rule should prescribe a frequency for the proposed periodic re-assessment of the fund's material valuation risks.[35] One commenter opposed the proposed requirement entirely, and suggested that the Commission remove references to valuation risk from the proposed rule, on the basis that identified valuation risks should have no impact on the actual fair valuing of particular fund investments, and that this requirement thus would unnecessarily complicate the final rule while providing no investor protection benefit.[36]

After considering these comments, we continue to believe that requiring the assessment and management of material valuation risks in the final rule will help promote an effective overall process for fair valuing fund investments in good faith.[37] With respect to the frequency of the required periodic re-assessment of valuation risks, we continue to believe that different frequencies for the re-assessment of valuation risks may be appropriate for different funds or risks, and have determined not to modify the proposed rule to include a required minimum frequency. We also continue to believe, as stated in the Proposing Release, that the periodic re-assessment of valuation risk generally should take into account changes in fund investments, significant changes in a fund's investment strategy or policies, market events, and other relevant factors.[38]

The Proposing Release also included a non-exhaustive list of examples of sources or types of valuation risk.[39] As discussed below, we are reiterating this non-exhaustive list here, with several modifications to broaden the examples to include additional sources and types of risk raised by commenters.

We received a number of comments on the list of sources and types of valuation risk. One commenter expressed general support for the inclusion of this list, including its level of generality in describing sources and types of risk.[40] One commenter, on the other hand, stated that this list would cause confusion because funds cannot anticipate how the identified sources and types of valuation risk will affect the valuation of particular investments.[41] One commenter stated that the text of the final rule should identify specific valuation risks (similar to the non-exhaustive list discussed in the Proposing Release) that a board or adviser, as applicable, must assess and manage.[42] Other commenters recommended that the Commission identify additional sources and types of valuation risks.[43]

One commenter recommended we clarify that the assessment and management of valuation risks other than those identified in the Proposing Release can satisfy this requirement.[44] Similarly, one commenter suggested we clarify that some sources or types of valuation risk may be considered more or less important than others based on a particular fund's investments, the markets in which its investments trade, reliance on third-party service providers, and other relevant circumstances.[45]

After considering these comments, we continue to believe that a fund's specific valuation risks depend on the facts and circumstances of the particular fund's investments. As such, we believe that the non-exhaustive list of examples of sources and types of valuation risk, set forth below, is appropriate. As we stated in the Proposing Release, the risks identified are not intended to be a comprehensive list of all possible sources of valuation risk, but a set of examples that may help inform fund boards and valuation designees. We agree that the additional risks identified by commenters may also be relevant for certain funds, and have broadened the list provided below in several respects to include those risks. The final rule, like the proposal, is designed to provide a board or valuation designee, as applicable, with the flexibility to determine which of the identified sources and types of valuation risk are relevant to the fund's investments, as well as to identify other risks not listed here. The final rule also provides flexibility to determine whether certain sources and types of valuation risk should be weighed more heavily than others.

As such, the following is a non-exhaustive list of sources or types of valuation risk:

- The types of investments held or intended to be held by the fund [46] and the characteristics of those investments; [47]

- Potential market or sector shocks or dislocations and other types of disruptions that may affect a valuation designee's or a third-party's ability to operate; [48]

- The extent to which each fair value methodology uses unobservable inputs, particularly if such inputs are provided by the valuation designee; [49]

- The proportion of the fund's investments that are fair valued as determined in good faith, and their contribution to the fund's returns;

- Reliance on service providers that have more limited expertise in relevant asset classes; the use of fair value methodologies that rely on inputs from third-party service providers; and the extent to which third-party service providers rely on their own service providers (so-called “fourth-party” risks); and

- The risk that the methods for determining and calculating fair value are inappropriate or that such methods are not being applied consistently or correctly.

2. Establish and Apply Fair Value Methodologies

As proposed, the final rule will provide that fair value as determined in good faith requires the board or valuation designee, as applicable, to establish and apply fair value methodologies. To satisfy this requirement, a board or valuation designee, as applicable, must:

(1) Select and apply appropriate fair value methodologies;

(2) Periodically review the appropriateness and accuracy of the methodologies selected and make any necessary changes or adjustments thereto; and

(3) Monitor for circumstances that may necessitate the use of fair value.

As discussed below, we are adopting these functions substantially as proposed, with certain modifications to respond to commenters' concerns and suggestions.

(a) Select and Apply Appropriate Fair Value Methodologies

The final rule will require the board or valuation designee, as applicable, to select and apply in a consistent manner an appropriate methodology or methodologies [50] for determining (which includes calculating) the fair value of fund investments.[51] As proposed, to satisfy this requirement, the board or valuation designee, as applicable, will have to specify the key inputs and assumptions specific to each asset class or portfolio holding.[52] We are, however, modifying the requirement to select and apply appropriate methodologies in the final rule in two ways to address commenter concerns and suggestions. First, the final rule will provide that the selected methodologies for fund investments may be changed if different methodologies are equally or more representative of the fair value of the investments. Second, the final rule will not require the specification of methodologies that will apply to new types of investments in which the fund intends to invest.

We received numerous comments on the proposed requirement that the board or adviser, as applicable, select and apply in a consistent manner an appropriate methodology or methodologies for determining (which includes calculating) the fair value of fund investments. These commenters generally requested clarification relating to the proposed requirement that a board or adviser, as applicable, select and apply fair value methodologies “in a consistent manner.” Several commenters stated that this proposed requirement suggested that a board or adviser, as applicable, generally may select only one methodology per asset class, and requested we clarify that this requirement does not preclude a board or adviser, as applicable, from selecting different methodologies for different securities within the same asset class or sub-class.[53] The final rule clarifies that this requirement is not meant to limit a board or valuation designee, as applicable, from using an appropriate methodology to fair value an investment, even if other investments within the same “asset class” are fair valued using a different appropriate methodology.

Similarly, commenters requested we clarify that the requirement to select and apply fair value methodologies in a consistent manner does not restrict a board's or adviser's ability to change the selected methodology for an investment or asset class under appropriate circumstances.[54] We recognize that there may be circumstances where it is appropriate to change a methodology if it would result in a measurement that is equally or more representative of fair value.[55] Accordingly, we have modified the final rule to clarify that the requirement to apply fair value methodologies in a consistent manner does not preclude the board or valuation designee, as applicable, from changing the methodology for an investment in such circumstances.[56] Applying a methodology consistently is not meant to lock in place a rigid pre-established methodology, but instead to address the risks associated with switching methodologies in order to achieve a specific outcome. Accordingly, the consistent application of appropriate methodologies allows for a board or valuation designee, as applicable, to select and apply a different methodology or methodologies for investments in the same asset class, or to change the methodology selected for one or more particular investments, based on changes to the facts and circumstances related to the particular investment if different methodologies are equally or more representative of the fair value of the investments.[57] Any change in methodology must be documented under the applicable recordkeeping requirements.[58]

Commenters questioned our statement in the Proposing Release that to be appropriate under rule 2a-5, a methodology used for purposes of determining fair value must be consistent with ASC Topic 820,[59] and thus must be derived from one of the principles-based approaches described therein.[60] Some of these commenters suggested that ASC Topic 820 is not appropriately tailored to address all of the specific circumstances that may arise for a fund that values its assets daily, and stated that we should either provide more specific guidance for certain funds or investments,[61] or not limit appropriate methodologies to those addressed in ASC Topic 820.[62]

We believe that an appropriate methodology must be consistent with those used to prepare the fund's financial statements and thus be consistent with the principles of the valuation approaches laid out in ASC Topic 820. Therefore, if a valuation methodology was used that is not consistent with the principles of the valuation approaches laid out in ASC Topic 820, we would presume that use of such a methodology would be misleading or inaccurate. While the valuation approaches laid out in ASC Topic 820 may not directly address every situation that a fund may face because the accounting standards are principles-based, we believe that taking a valuation approach that is inconsistent with the principles outlined in ASC Topic 820 may result in a fund having a misleading or inaccurate fair value process because such an approach may not be consistent with U.S. GAAP and the fund's financial reporting process. Supplemental methodologies for situations not explicitly outlined in ASC Topic 820 may be appropriately applied by boards or valuation designees provided that the methodologies are not inconsistent with the principles outlined in ASC Topic 820. We recognize that there is no single methodology for determining the fair value of an investment because fair value depends on the facts and circumstance of each investment, including the relevant market and market participants.[63] We continue to believe that for any particular investment, there may be a range of appropriate values that could reasonably be considered to be fair value, and whether a specific value should be considered fair value will depend on the facts and circumstances of the particular investment. A consistent application of the selected methodology or methodologies, with changes to the methodology or methodologies where appropriate, together with the other provisions of the rules, would promote unbiased determinations of fair value within the range.

Commenters suggested we clarify that certain guidance provided in the 2014 Money Market Funds Adopting Release relating to the valuation of thinly traded securities is being superseded by final rule 2a-5 and the related guidance provided herein.[64] We believe that the guidance contained in this section addresses the same concerns discussed in the guidance contained in the last paragraph of the section on valuing thinly traded securities in the 2014 Money Market Funds Adopting Release.[65] Accordingly, that paragraph is superseded. As a general principle, determining fair value requires taking into account market conditions existing at the time of the determination. Accordingly, appropriate methodologies for funds holding debt securities generally should not fair value these securities at par or amortized cost based on the expectation that the funds will hold those securities until maturity, if the funds could not reasonably expect to receive approximately that value upon the measurement date under current market conditions. We continue to believe that fair value cannot be based on what a buyer might pay at some later time, such as when the market ultimately recognizes the security's true value as currently perceived by the portfolio manager.[66] Funds also may not fair value portfolio securities at prices not achievable on a current basis on the belief that the fund would not currently need to sell those securities. We believe the principles established in ASC Topic 820, which provide that an investment is valued based on an exit price at the measurement date from the perspective of a market participant under current market conditions, are consistent with the statements in this paragraph.[67]

The proposed rule also would have required the board or adviser, as applicable, to consider the applicability of the selected fair value methodologies to types of fund investments that a fund does not currently hold but in which it intends to invest in the future.[68] This requirement was designed to facilitate the effective determination of the fair value of these new investments by the board or adviser, as applicable. While one commenter suggested that this requirement was appropriate as proposed,[69] other commenters generally opposed this requirement as being potentially overly burdensome by requiring boards and advisers to establish a predetermined list of methodologies to account for all types of new investments in which the fund may invest.[70]

We are persuaded that specifically requiring a predetermination of the methodologies that must be applied to hypothetical future investments could cause undue burdens to the extent it caused a fund to establish methodologies for assets in which a fund ultimately does not invest. Moreover, a fund will be required to value all of its investments, regardless of whether the fund had pre-determined a methodology. We believe that the general requirement under the final rule to select and apply in a consistent manner an appropriate methodology or methodologies for determining (and calculating) the fair value of fund investments,[71] will require a board or a valuation designee, where applicable, to determine which methodology is appropriate for a new investment type that a fund has actually purchased by the time the investments are valued. Accordingly, we have determined to remove from the final rule the proposed specific requirement that a board or adviser, as applicable, specify in advance the fair value methodologies that will apply to new types of investments in which the fund intends to invest.

(b) Periodically Review the Appropriateness and Accuracy of the Methodologies Selected

To establish and apply fair value methodologies appropriately, the final rule will require a board or valuation designee to review periodically the selected fair value methodologies for appropriateness and accuracy, and to make changes or adjustments to the methodologies where necessary.[72] We are adopting this requirement substantially as proposed, with one modification, discussed below, to respond to a comment we received. In addition, as stated in the Proposing Release, the results of back-testing or calibration (as discussed below) or a change in circumstances specific to an investment, for example, could necessitate adjustments to a fund's fair value methodologies.[73]

We received one comment on this requirement. The commenter generally supported it, but suggested we clarify that “adjustments” to the selected fair value methodologies under this requirement may include a change to new appropriate methodologies.[74] We agree, and have added the word “change” to the final rule to clarify that a necessary adjustment to the selected methodology under the final rule is not limited to modifying an existing methodology for a particular investment (for example, adjusting inputs), but also may include changing to a new methodology where appropriate.[75]

(c) Monitor for Circumstances That May Necessitate the Use of Fair Value

As proposed, the final rule will also require the board or valuation designee, as applicable, to monitor for circumstances that may necessitate the use of fair value as determined in good faith.[76] For example, if a fund invests in securities that trade in foreign markets, the board or valuation designee, as applicable, generally should identify and monitor for the kinds of significant events that, if they occurred after the market closes in the relevant jurisdiction but before the fund prices its shares, would materially affect the value of the security and therefore may suggest that market quotations are not reliable.[77]

One commenter generally requested we clarify that this requirement is not meant to require the board or valuation designee, where applicable, to identify in advance all of the circumstances that may require the use of fair value.[78] While we agree that the circumstances that may necessitate fair value depend on the facts and circumstances of the particular fund's investments and that certain of these circumstances cannot be established in advance, we also believe that monitoring for circumstances that may require the use of fair value is an important element of an effective overall process for determining fair value in good faith.

The proposed rule also would have required the establishment of criteria for determining when market quotations are no longer reliable and therefore not readily available.[79] One commenter viewed this proposed requirement as potentially being overly restrictive of boards' and advisers' discretion to question the reliability of market quotations, and suggested we remove it from the final rule.[80] Another commenter suggested that requiring a board or adviser to identify in advance all of the criteria indicating when a market quotation may not be reliable would be overly burdensome.[81]

Although this requirement derived from the Commission's positions under the compliance rule,[82] we have determined to remove it from the final rule. We agree with commenters that requiring, in advance, a list of specific criteria for determining when market quotations may no longer be reliable could limit the board's or valuation designee's flexibility to consider the full range of conditions that may affect the reliability of market quotations. In addition, we believe that to satisfy the requirement to monitor for circumstances that may necessitate the use of fair value, discussed above, boards and valuation designees would have to take into account the circumstances that may cause market quotations to be no longer reliable. The final rule, however, will not require those broader circumstances to be captured in specific criteria.

3. Test Fair Value Methodologies for Appropriateness and Accuracy

As proposed, the final rule will require the testing of the appropriateness and accuracy of the methodologies used to calculate fair value.[83] This requirement is designed to help ensure that the selected fair value methodologies are appropriate and that adjustments to the methodologies are made where necessary. The final rule, similar to the proposal, will require the board or valuation designee, as applicable, to identify the testing methods to be used and the minimum frequency with which such testing methods are used, but will not require particular testing methods or a specific minimum frequency for the testing.

While several commenters supported the proposed requirement,[84] other commenters recommended that we modify or clarify the requirement in the final rule. One commenter recommended that we remove from the final rule the proposed requirement that the adviser or board identify the testing methods to be used and the minimum frequency with which such testing methods are used, viewing it as overly prescriptive and too limiting of the discretion of the board or adviser, as applicable, to determine how testing should be conducted.[85] Several commenters recommended we clarify that parties other than the board or adviser, as applicable, such as pricing services, may perform the testing.[86] One commenter asked that we provide a de minimis exception to the proposed testing requirement for funds that have a limited amount of fair valued investments.[87] Finally, one commenter recommended that the final rule require that methodology testing be performed at least quarterly or whenever the fund provides financial statements to investors.[88]

After considering these comments, we continue to believe that the specific tests to be performed and the frequency with which such tests should be performed are matters that depend on the circumstances of each fund and thus should be determined by the board or the valuation designee, as applicable. We also continue to believe that requiring the identification of (1) the testing methods to be used, and (2) the minimum frequency of the testing, is appropriate and still provides boards and valuation designees with flexibility to perform methodology testing based on the particular circumstances of a particular fund.[89] We believe that funds that have even a limited amount of fair valued investments should test their methodologies, and therefore are not providing a de minimis exception.[90] Testing can often reveal important information about the continuing appropriateness of a methodology. We expect the frequency and nature of testing would vary depending on the type and amount of investments held by the fund. If a specific methodology consistently over-values or under-values one or more fund investments as compared to observed transactions, the board or valuation designee, as applicable, should investigate the reasons for this difference.

Calibration and back-testing are examples of particularly useful testing methods to identify trends in certain circumstances, and potentially to assist in identifying issues with methodologies applied by fund service providers, including poor performance or potential conflicts of interest.[91] Several commenters recommended we clarify that this statement is not meant to suggest that calibration and back-testing are required testing methods, or that the use of appropriate testing methods other than calibration and back-testing would not satisfy the testing requirement.[92] While we believe that calibration and back-testing are methods that should be used for testing the appropriateness and accuracy of funds' fair value methodologies in many circumstances, the final rule does not require calibration and back-testing, nor does it preclude boards or valuation designees, where applicable, from using other appropriate testing methods.[93] We expect that as testing methodologies are developed and change over time, new and different tools for testing may also become more prominent or useful. The final rule provides flexibility to allow funds to use new, appropriate testing methods.

4. Pricing Services

As proposed, the final rule will provide that determining fair value in good faith requires the oversight and evaluation of pricing services, where used.[94] For funds that use pricing services, the final rule will require that the board or valuation designee, as applicable, establish a process for approving, monitoring, and evaluating each pricing service provider. The final rule also will require that the board or valuation designee, as applicable, establish a process for initiating price challenges as appropriate. Commenters generally supported the proposal to require the board or adviser, as applicable, to oversee and evaluate pricing services.[95] One commenter, however, stated that this oversight provision is unnecessary in the case of pricing services that are not affiliated with the fund's adviser.[96] This commenter stated that pricing services should not be distinguished from other third-party fund service providers, which advisers oversee to meet their own fiduciary obligations. Another commenter questioned the significance of a pricing service's conflicts of interest, stating that pricing services maintain relationships with a wide variety of investment advisers, and generally are expected to provide the same valuation information with respect to a particular security to all funds.[97] As a result, this commenter asserted that it would be less likely for a pricing service to be unduly pressured to provide favorable information in a particular scenario or to a particular investment adviser. We believe, however, that the conflict is not necessarily one of responding to pressure from a particular investment adviser, but, rather, a pricing service might generally provide higher or more aggressive valuations to retain business.

We believe, and many commenters agreed, that pricing services play an important role in the fair value process by providing information on evaluated prices, matrix prices, price opinions, or similar pricing estimates or information that can assist in determining the fair value of fund investments.[98] Additionally, we believe that pricing services may have conflicts of interest such as maintaining continuing business relationships with the valuation designee. Therefore, given the widespread reliance on pricing services, the critical role they play in the valuation of fund investments, and their potential conflicts of interests, regardless of whether they are affiliated with the fund's adviser, the final rule will require that pricing services be subject to oversight so that the board or valuation designee, as applicable, has a reasonable basis to use the pricing information it receives as an input in determining fair value in good faith. To oversee pricing services effectively, the board or valuation designee, as applicable, should establish a process for the approval, monitoring, and evaluation of each pricing service provider used.

In a change from the proposal, we are modifying the final rule to require funds to establish a process for initiating price challenges as appropriate, instead of the proposed approach that would have required funds to establish criteria for the circumstances under which price challenges would be initiated.[99] Many commenters stated that requiring funds to establish specific criteria, such as objective thresholds, for price challenges was too rigid. Commenters were concerned that this would result in rote or mechanical price challenges that may be unnecessary, while not covering price challenges that may be appropriate based on facts and circumstances not readily susceptible to being distilled into criteria specified in advance.[100] Commenters stated that the circumstances under which a fund might initiate a price challenge are not always objective or based on set criteria given the myriad of different, and often fluid, data sources and inputs that could lead to challenges.[101]

After considering comments, we agree that there can be a range of circumstances under which a price challenge may be warranted, some of which cannot be distilled into specific criteria in advance.[102] For example, such an approach may lead the valuation designee to challenge pricing information that is reasonable given market conditions, solely because such pricing information meets the pre-established criteria. We believe, however, that appropriate oversight of pricing services includes a rigorous analysis of the pricing information provided by pricing services and any price challenges, where appropriate. Therefore, we are amending this requirement to require that funds establish a process for initiating price challenges, instead of pre-established criteria.[103] Such a process generally should outline the circumstances under which a price challenge should be initiated.[104]

Several commenters urged the Commission to provide additional guidance concerning who would qualify as a pricing service under the final rule.[105] Two commenters stated that the term “pricing service” as used in the Proposing Release is not entirely consistent with the definition in the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) standards for auditing fair value measurements.[106] We are not adopting a specific list of criteria for who may qualify as a pricing service because we believe that it may become outdated over time and that the scope of the term “pricing service” is generally understood by boards and valuation designees. However, as we stated in the Proposing Release, we refer to pricing services as third parties that regularly provide funds with information on evaluated prices, matrix prices, price opinions, or similar pricing estimates or information to assist in determining the fair value of fund investments.[107] We believe that the types of entities that would be pricing services under the final rule would include pricing services as defined in the PCAOB standards.[108]

Some commenters suggested we also include a specific requirement for a fund's board or adviser, as applicable, to periodically review the selection of pricing services and to evaluate other pricing services.[109] Two commenters, in contrast, stated that such a requirement would be unnecessary because the compliance rule already requires periodic reviews of service providers, including fund pricing services.[110] We believe that a specific requirement to review the selection of pricing services is unnecessary in light of the reporting requirements of rule 2a-5, discussed below.[111] We think that the board or the valuation designee should, as part of their annual review of the adequacy and effectiveness of the fair value process, consider the adequacy and effectiveness of the pricing services used given the important role that information provided by pricing services can play in the fair value process.

In addition, several commenters stated that the oversight of pricing services requirements under rule 2a-5 may not be consistent with previous guidance regarding the use of pricing services in the 2014 Money Market Fund Release, particularly regarding the role of the board of directors.[112] Some of these commenters urged us to rescind that guidance and holistically address oversight of pricing services in this Adopting Release.[113]

We believe that the requirements of the final rule and the guidance provided in this section effectively address the concerns with oversight of pricing services discussed as part of the fair value guidance in the 2014 Money Market Fund Release. We state below our views on how oversight and selection of pricing services may be effectively conducted, which is largely consistent with our previous guidance from the 2014 Money Market Fund Release guidance but reflects the process established in rule 2a-5 allowing the board to designate the valuation designee to perform fair value determinations.[114] The guidance below also includes certain additional factors that were included in the Proposing Release.[115] Our views stated below supersede the guidance the Commission expressed in the 2014 Money Market Fund Release regarding the use of pricing services, and so we are rescinding that guidance.[116]

We believe that under the final rule, before deciding to use a pricing service, the fund's board or valuation designee, as applicable, generally should take into consideration factors such as: (i) The qualifications, experience, and history of the pricing service; (ii) the valuation methods or techniques, inputs, and assumptions [117] used by the pricing service for different classes of holdings, and how they are affected (if at all) as market conditions change; [118] (iii) the quality of the pricing information provided by the service and the extent to which the service determines its pricing information as close as possible to the time as of which the fund calculates its net asset value; [119] (iv) the pricing service's process for considering price challenges, including how the pricing service incorporates information received from price challenges into its pricing information; (v) the pricing service's actual and potential conflicts of interest and the steps the pricing service takes to mitigate such conflicts; [120] and (vi) the testing processes used by the pricing service.[121] In addition, the fund's board or valuation designee, as applicable, should generally consider the appropriateness of using pricing information provided by a pricing service in determining the fair values of the fund's investments where, for example, the fund's board or valuation designee, as applicable, does not have a good faith basis for believing that the pricing service's pricing methodologies produce prices that reflect fair value.[122]

5. Fair Value Policies and Procedures

The final rule does not include the provision in the proposal that would have separately required the fund to adopt written policies and procedures reasonably designed to achieve compliance with the requirements of rule 2a-5.[123] While commenters generally supported this requirement,[124] other commenters argued that policies and procedures required by the proposed rule are already required by the compliance rule and urged the Commission to clarify the interaction between fund obligations under the compliance rule and the policies and procedures required under the proposed rule.[125]

Rule 38a-1 requires a fund's board, including a majority of its independent directors, to approve the fund's policies and procedures, and those of each adviser and other specified service providers, based upon a finding by the board that the policies and procedures are reasonably designed to prevent violation of the Federal securities laws.[126] We agree that, after our adoption of rules 2a-5 and 31a-4, the compliance rule by its terms will require the adoption and implementation of written policies and procedures reasonably designed to prevent violations of the requirements of rules 2a-5 and 31a-4 (“fair value policies and procedures”).127 Accordingly, final rule 2a-5 does not include a separate policies and procedures requirement.

While the adopting release for the compliance rule included a discussion of certain policies and procedures for determination of fair value that a fund should adopt, this discussion occurred prior to our adoption of rule 2a-5.[128] Rule 2a-5 creates a new framework for fair value determinations. As we stated in the Proposing Release, the requirements of rule 2a-5 and guidance in this release will supersede the Compliance Rules Adopting Release's discussion of policies and procedures for the pricing of portfolio securities and fund shares.[129] Accordingly, to comply with the compliance rule, each fund must adopt and implement fair value policies and procedures that are reasonably designed to prevent violations of new rules 2a-5 and 31a-4's requirements. Because rules 2a-5 and 31a-4 are new rules under the Act with new fair value determination requirements, and given the intrinsic relationship of the rules to the board's own statutory functions relating to valuation, the fair value policies and procedures must be approved by the board pursuant to rule 38a-1 and may not be considered material amendments to existing fair value policies and procedures.[130]

Where the board determines the fair value of investments, the fund will adopt and implement the fair value policies and procedures under the compliance rule.[131] Similarly, where the board designates the adviser as valuation designee to perform fair value determinations under rule 2a-5(b), as discussed in section II.B, the adviser will adopt and implement the fair value policies and procedures under the compliance rule. As with a fund adopting fair value policies and procedures, the adviser's fair value policies and procedures must be approved by the board pursuant to rule 38a-1 and may not be considered material amendments to existing fair value policies and procedures. This approach clarifies, as some commenters requested, that the board can fulfill its responsibilities under the compliance rule if the adviser adopts fair value policies and procedures without the need for the fund to adopt duplicative policies separately.[132] Additionally, we believe that this approach helps to ensure that fair value policies and procedures include an appropriate amount of detail, while preserving a certain level of flexibility for the board or adviser, as applicable, to tailor the fair value policies and procedures to the unique facts and circumstances of the fund.[133]

B. Performance of Fair Value Determinations

Largely as proposed, under the final rule, a board may choose to determine fair value in good faith for any or all fund investments by carrying out all of the functions required in paragraph (a) of the final rule, including, among other things, selecting and applying valuation methodologies.[134] A board could also designate the performance of fair value determinations relating to any or all fund investments to a valuation designee, subject to the board's oversight. The final rule will require the valuation designee to make certain reports to the board, specify responsibilities regarding fair value determinations, and reasonably segregate portfolio management from fair value determinations.[135] The trustee or depositor will generally perform the fair value functions in paragraph (a) of the final rule for UITs, which do not have a board or adviser.[136] These provisions are designed to provide boards, valuation designees, and other parties involved with a consistent approach to the allocation of fair value functions that recognizes the important role that valuation designees can play in the fair value process, while also preserving a crucial role for boards to fulfill their obligations under section 2(a)(41) of the Act by meeting the requirements of the final rule.[137]

Designate or Assign

Section 2(a)(41) requires that the board determine fair value for securities that do not have readily available market quotations. The final rule provides that the board may “designate” the performance of these fair value determinations to a valuation designee. This is a change from the proposal that would have provided that the board may “assign” such task to an adviser. Some commenters questioned the use of the phrase “assign” in the proposed rule, stating that it was unique in the rules adopted under the Act. These commenters stated that the scope of an assignment was unclear.[138] One such commenter observed that other terms, such as “designate,” are used in other Commission rules and connote choosing a party for a particular purpose.[139] After considering comments, we believe that a board “designating” a valuation designee to perform fair value determinations better describes the relationship between the board and valuation designee under the final rule—that is, one where the valuation designee performs the fair value determinations for the fund on the board's behalf subject to appropriate oversight by the fund's board. Some commenters believed that the term “assign” could suggest that the board has completely delegated the entire valuation function and related obligations to the adviser.[140] We do not intend this result. Accordingly, the final rule uses the term “designate” instead of “assign.”

Who May Be Designated

In a change from the proposal, which would have permitted boards to assign only to an adviser of the fund, the final rule will permit boards to designate the fund's adviser to perform fair value determinations or, if the fund is internally managed, an officer of the fund.[141] Many commenters recommended that we expand the types of entities that could perform fair value determinations on behalf of the board beyond the fund's adviser. Commenters suggested that we permit any affiliate of the adviser; [142] fund administrators and affiliates; [143] committees composed of a blend of personnel or officers of the fund, adviser, or administrator; [144] pricing services; [145] accounting firms; [146] or any party the board has determined has sufficient expertise and capacity to conduct the fair value determinations.[147] Some also recommended that we permit officers of internally managed funds to conduct this activity because these funds do not have advisers.[148]

These commenters suggested that an expanded list of permissible entities would more accurately reflect current organizational structures and practices, would make it easier for smaller funds to comply with rule 2a-5, and would facilitate boards that would prefer non-advisers that may have fewer conflicts of interest.[149] Some commenters believed it was unnecessary for the party performing fair value determinations to be a fiduciary of the fund.[150] In contrast, others suggested that a fiduciary relationship is important.[151]

We generally decline to expand permissible designees beyond the adviser in the final rule because we believe that it is critical for the entity actually performing the fair value determinations to owe a fiduciary duty to the fund and be subject to direct board oversight whenever possible.[152] While these other parties may not have the same conflicts as an adviser, they also generally have other conflicts that could influence their fair value determinations. For example, pricing services may have an interest in maintaining continuing business relationships with the adviser or fund, which could present conflicts [153] and in such cases, unlike advisers,[154] their performance of fair value determinations may not be subject to the same fiduciary obligations owed to the fund.[155] We believe that having fiduciary obligations to the fund will help ensure that the party performing fair value determinations acts in the fund's best interest and, as appropriate, eliminates, mitigates, or discloses conflicts.[156] Further, we believe that it is important for the valuation designee to have a direct relationship with the fund's board and have comprehensive and direct knowledge of the fund.[157] This is true of the fund's adviser, whose advisory contract is subject to substantive board oversight pursuant to the Act,[158] or, in the case of internally-managed funds, officers of the fund. To the extent that other parties provide services that are essential for fair value determinations, the board or valuation designee can seek their assistance as discussed below.

We recognize, as commenters stated, that internally managed funds have no adviser. Instead they rely on certain officers of the fund to perform the broad range of tasks that advisers to externally managed funds otherwise perform.[159] These officers also have fiduciary duties,[160] and as employees of the fund are subject to oversight by the fund's board of directors. We believe that internally managed funds should not be excluded from this provision of the final rule solely because they have no adviser. Thus, in a change from the proposal, the final rule also permits such a fund's board to designate an officer or officers of the fund to perform the fair value determinations if the fund does not have an adviser.[161]

In the Proposing Release, we stated that the proposed rule would permit boards to assign either to the fund's primary adviser or one or more sub-advisers.[162] While some commenters generally supported the flexibility this interpretation would afford,[163] others opposed or had concerns about it, arguing that sub-advisers do not currently perform this task and permitting them to do so could significantly increase costs.[164] Some did not object to the flexibility but stated that having sub-advisers involved in valuation was inconsistent with some current practices, with some questioning if this would be an appropriate role for a sub-adviser.[165] A number of commenters raised concerns about how permitting assignment to sub-advisers would work in practice, for example, how to resolve conflicting fair value determinations,[166] and requested that we provide guidance on how to reconcile in such circumstances.[167]

The final rule will not permit boards to designate the performance of fair value determinations to fund sub-advisers.[168] However, consistent with the guidance below, boards or their valuation designee can seek the assistance of sub-advisers as they see appropriate. We proposed allowing designation to sub-advisers as a method to provide additional flexibility to boards. After considering the increased complexity identified by commenters that this flexibility may create, and commenters' assertions that sub-advisers typically do not currently serve in this role,[169] we have determined that any benefits provided by this additional flexibility would not be justified by the additional challenges it may create. We also are concerned that allowing designation to sub-advisers may create complicated reconciliation and oversight issues for boards, advisers, and sub-advisers. However, we welcome engagement with respect to the role of sub-advisers in the fair value determination process.

The proposed rule would have permitted only the UIT's trustees to perform fair value determinations.[170] Commenters stated that the final rule should permit the parties specified as evaluators in the UIT's trust indenture or similar document, including the depositor and other entities, to perform fair value determinations under rule 2a-5. These commenters argued that these evaluators are the entities with relevant expertise in valuation matters and this change would make rule 2a-5 more consistent with current practice.[171] Others asked that we not apply the final rule's requirements to existing UITs given their trust indentures are currently drafted to permit entities other than trustees to value the UITs' investments.[172] One commenter stated that the cost to implement the proposed rule could be significant for UITs due to the change in practice.[173]

In other contexts under the Investment Company Act, the Commission has provided for a UIT's depositor to conduct activities that the board of directors would otherwise conduct, given that a UIT has neither a board of directors nor an adviser.[174] UIT depositors are subject to liability under section 36(a) of the Act for breach of fiduciary duty.[175] We agree, in light of these comments, that UITs should not be limited to trustees to perform their fair value determinations. As we understand that the trustee traditionally has not performed fair value determinations, and we have recognized in the past that depositors generally serve the most equivalent function to an adviser for UITs,[176] the final rule will permit either the fund's depositor or trustee to perform the fair value determinations required under rule 2a-5.[177] To the extent that the assistance of other parties (such as evaluators) is necessary, trustees or depositors can seek that assistance consistent with the guidance below regarding obtaining the assistance of others.

In recognition of commenters' statements that there would be significant costs for pre-existing UITs to change who engages in the fair value determination as they might need to amend their trust indenture (and potentially obtain a unit holder vote approving the change) we are grandfathering existing UITs under limited circumstances. Thus, the final rule will now require trustees or depositors to perform fair value determinations if the UIT's date of initial deposit (which would include a rollover) of portfolio securities occurred after the effective date of rule 2a-5. If the initial deposit of securities into the UIT took place prior to the effective date of the final rule, to the extent that an entity other than the UIT's trustee or depositor has been designated in the trust indenture to perform fair value determinations, that previously designated entity may perform such fair value determinations pursuant to paragraph (a) of the final rule.[178] We believe that this approach should be acceptable, even though the party making fair value determinations under this provision may not be subject to the same fiduciary duties, as this outcome reflects a balancing of the costs and risks, informed by the unmanaged and fixed nature of these UITs, and because of the limited nature of this relief.[179] Further, we believe that the number of these funds that will be able to utilize an entity other than a depositor or trustee will be small and decrease over time.[180] We are also concerned that it would be unlikely that pre-existing UITs could comply with the final rule absent this provision given the statutory requirement that UITs be organized under a trust indenture, contract of custodianship or agency, or similar instrument (the terms of which, in these limited cases, provide for an evaluator other than the trustee or depositor). Further, we believe that this approach should address commenter concerns about disrupting existing UIT fair value determination designees and the associated potential costly changes which could affect investors if the costs are passed on to them.

As proposed, the final rule defines “board” both as the full board or a designated committee thereof composed of a majority of directors who are not interested persons of the fund.[181] We received limited comments on this aspect of the proposal. One commenter, however, suggested that the fund should be required to develop policies and procedures for when the whole board, rather than a committee, would be required to be involved.[182] Conversely, another stated that because state law permits fund boards to empower specific committees to act on behalf of the entire board, rule 2a-5 was sufficient as proposed.[183] We believe that no such changes are necessary to this provision because it is important that boards be able to utilize specialized committees, particularly on matters as detailed and important as valuation. Should a fund choose to develop policies and procedures regarding when a matter is more appropriate for the full board, it can do so, but it will not be required under the final rule.

One commenter wanted clarification that the fund's adviser could perform fair value determinations on the board's behalf regardless of whether it is acting pursuant to an advisory contract, administrative contract, or similar agreement.[184] Another asked that we clarify when a pricing service that is a Commission-registered adviser would be considered an “investment adviser” for purposes of the final rule.[185] The final rule, consistent with the proposal, provides that where the valuation designee is an adviser, it must be an “adviser of the fund.” This would not include other service providers, whether or not they are registered as advisers, or acting under a contract with the fund, unless they are actually serving as the adviser of the fund as defined under the Investment Company Act because they may not have a comprehensive and direct knowledge of the fund, a direct relationship with the board, or the same fiduciary duties to the fund in other cases.[186] As discussed above, it also would not include a sub-adviser to the fund.

Guidance on Obtaining the Assistance of Others

Some commenters also asked that we clarify that the adviser or the fund board could engage third parties to assist with certain functions of the fair value determination process, such as performing back-testing, fund accounting, or shareholder reporting, other than making the actual determinations themselves.[187] Others urged us to state that advisers assigned to perform fair value determinations under the proposed rule could, in turn, assign their responsibilities to other third parties.[188]

We believe that whether the board or the valuation designee makes fair value determinations under the final rule, it may of course obtain assistance from others in fulfilling its duties. It may, for example, seek assistance from pricing services, fund administrators, sub-advisers, accountants, or counsel.[189] That assistance can take different forms, and may include services such as performing back-testing as specified by the valuation designee and performing calculations required by the valuation method selected by the board or valuation designee. The board or the valuation designee, using this assistance, must of course also perform its responsibilities under the Act, the final rule, and other applicable rules under the Act. However, in seeking the assistance of others, the entity or officer designated to perform the fair value determination remains responsible for that determination and may not designate or assign that responsibility to the third party for the same reasons we are not permitting the board to designate performance of this task to a party other than the valuation designee.[190]

1. Board Oversight

The final rule, consistent with the proposal, specifically requires a board to oversee the valuation designee if the board has designated the performance of fair value determinations to the valuation designee.[191] In the proposal, we provided guidance on our expectations related to this board oversight.[192] A number of commenters supported this guidance,[193] with one commenter stating that the discussion properly reflects the general roles of boards and advisers under both current practices of properly functioning boards as well as Federal and state law.[194] However, other commenters questioned parts of the guidance or asked that we provide further guidance on certain issues.

Some of these commenters argued that board oversight of the valuation process should be the same as the oversight of other functions, such as liquidity risk.[195] While we agree that boards should provide oversight in those contexts as well, we believe that we should provide specific guidance with respect to board oversight in the context of making fair value determinations. We believe that specific guidance is appropriate because section 2(a)(41) is one of the few provisions of the Act that specifically imposes a requirement on fund boards, requiring boards to determine fair value in good faith. Therefore, this guidance supports our view that a board may still satisfy its statutory obligation to determine fair value even though it has designated another entity to perform the fair value determinations under the final rule, subject to appropriate oversight.[196]

A number of commenters questioned the guidance stating that boards must be active in their oversight role by probing reports written by advisers and being inquisitive,[197] but other commenters agreed that board oversight cannot be a passive activity.[198] We believe that boards are not providing appropriate oversight if they simply rely on information presented to them without actively probing it, asking questions, and seeking relevant information, particularly when there are red flags or other indications of problems. Some commenters asked us to state that the board does not have an independent duty to seek to discover conflicts of interest but can reasonably rely upon the adviser's identification of these conflicts,[199] but one stated we should clarify that the board has an affirmative duty to do so.[200] Another stated that the board should be able to rely upon the adviser much the same way that it can reasonably rely upon others, such as fund CCOs, administrators, and counsel.[201] As discussed below in the guidance on board oversight, we are reiterating our belief, stated in the Proposing Release, that boards should seek to identify potential conflicts of interest as part of their oversight duties under the final rule. Boards must work with valuation designees, which also have a duty to disclose their conflicts,[202] to address or manage these conflicts to the board's satisfaction.

Although several commenters asked us to confirm that boards may provide oversight of the performance of fair value determinations consistent solely with the business judgment rule under state law, we decline to do so.[203] Instead, we are providing guidance that we believe should be more useful to directors than the more generalized principles of the business judgment rule, as this new guidance specifically relates to directors' oversight responsibilities under section 2(a)(41) of the Act and the final rule.

Finally, several commenters recommended that we adopt additional oversight requirements, such as third-party reviews, attestations, or certifications by the adviser,[204] or that we require the board to make specific findings.[205] Others argued that additional requirements were unnecessary due to state law duties applicable to boards or because the expense was not justified by the regulatory benefits.[206] Several commenters also asked that we clarify whether directors are expected to ratify fair value determinations made by the adviser under rule 2a-5.[207] We are not adding specific oversight requirements in the final rule beyond those that were proposed. We believe that the oversight requirements of boards under the final rule, discussed below, taken together with the directors' fiduciary duties, are reasonably designed to establish a minimum set of requirements for addressing the conflict of interest and other concerns associated with permitting a valuation designee to make fair value determinations. As such, we believe that additional requirements like those suggested by these commenters may be duplicative or involve burdens that are not justified by their potential benefits. The final rule does not require boards to ratify fair value determinations made by the valuation designee, as we believe it is not a necessary component of active oversight.

Guidance on Board Oversight

We reiterate the guidance on board oversight of the fair value determination process from the Proposing Release.[208] When the board designates the performance of fair value determinations to the valuation designee, the final rule will require the board to satisfy its statutory obligation with respect to these determinations through the framework of rule 2a-5, including overseeing the valuation designee. Boards should approach their oversight of the performance of fair value determinations by the valuation designee of the fund with a skeptical and objective view that takes account of the fund's particular valuation risks, including with respect to conflicts, the appropriateness of the fair value determination process, and the skill and resources devoted to it.[209] Further, in our view appropriate oversight cannot be a passive activity. Directors should ask questions and seek relevant information.

The board should view oversight as an iterative process and seek to identify potential issues and opportunities to improve the fund's fair value processes.[210] The final rule will require the valuation designee to report to the board with respect to matters related to the valuation designee's fair value process, in part to ensure that the board has sufficient information to conduct this oversight.[211] Boards should also request follow-up information when appropriate and take reasonable steps to see that matters identified are addressed.[212]

We expect that boards engaged in this process would use the appropriate level of scrutiny based on the fund's valuation risk, including the extent to which the fair value of the fund's investments depend on subjective inputs. For example, a board's scrutiny would likely be different if a fund invests in publicly traded foreign companies than if the fund invests in private early stage companies. As the level of subjectivity increases and the inputs and assumptions used to determine fair value move away from more objective measures, we expect that the board's level of scrutiny would increase correspondingly.[213]

We also believe that, consistent with their obligations under the Act and as fiduciaries, boards should seek to identify potential conflicts of interest, monitor such conflicts, and take reasonable steps to manage such conflicts.[214] In so doing, the board should serve as a meaningful check on the conflicts of interest of the valuation designee and other service providers involved in the determination of fair values.[215] In particular, the fund's adviser may have an incentive to value fund assets improperly in order to increase fees, improve or smooth reported returns, or comply with the fund's investment policies and restrictions.[216] Other service providers, such as pricing services or broker-dealers providing opinions on prices, may have incentives (such as maintaining continuing business relationships with the valuation designee) [217] or may otherwise be subject to pressures to provide pricing estimates that are favorable to the valuation designee.[218] In overseeing the valuation designee's process for making fair value determinations, the board should understand the role of, and inquire about conflicts of interest regarding, any other service providers used by the valuation designee as part of the process, and satisfy itself that any conflicts are being appropriately managed.

Boards should probe the appropriateness of the valuation designee's fair value processes. In particular, boards should periodically review the financial resources, technology, staff, and expertise of the valuation designee, and the reasonableness of the valuation designee's reliance on other fund service providers, relating to valuation.[219] In addition, boards should consider the valuation designee's compliance capabilities that support the fund's fair value processes, and the oversight and financial resources available for the fair value process.