AGENCY:

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Department of Homeland Security.

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

This final rule amends Department of Homeland Security (“DHS” or “the Department”) regulations governing petitions filed on behalf of H-1B beneficiaries who may be counted toward the 65,000 visa cap established under the Immigration and Nationality Act (“H-1B regular cap”) or beneficiaries with advanced degrees from U.S. institutions of higher education who are eligible for an exemption from the regular cap (“advanced degree exemption”). The amendments require petitioners seeking to file H-1B petitions subject to the regular cap, including those eligible for the advanced degree exemption, to first electronically register with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (“USCIS”) during a designated registration period, unless the registration requirement is temporarily suspended. USCIS is suspending the registration requirement for the fiscal year 2020 cap season to complete all requisite user testing of the new H-1B registration system and otherwise ensure the system and process are operable.

This final rule also changes the process by which USCIS counts H-1B registrations (or petitions, for FY 2020 or any other year in which the registration requirement will be suspended), by first selecting registrations submitted on behalf of all beneficiaries, including those eligible for the advanced degree exemption. USCIS will then select from the remaining registrations a sufficient number projected as needed to reach the advanced degree exemption. Changing the order in which USCIS counts these separate allocations will likely increase the number of beneficiaries with a master's or higher degree from a U.S. institution of higher education to be selected for further processing under the H-1B allocations. USCIS will proceed with implementing this change to the cap allocation selection process for the FY 2020 cap season (beginning on April 1, 2019), notwithstanding the delayed implementation of the H-1B registration requirement.

DATES:

This final rule is effective April 1, 2019.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Elizabeth Buten, Adjudications (Policy) Officer, Office of Policy and Strategy, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Department of Homeland Security, 20 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Suite 1100, Washington, DC 20529-2140; Telephone (202) 272-8377.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Table of Contents

I. Executive Summary

A. Purpose and Summary of the Regulatory Action

B. Legal Authority

C. Summary of Changes From the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

D. Summary of Costs and Benefits

E. Effective Date

F. Implementation

II. Background

A. The H-1B Visa Program and Numerical Cap and Exemptions

B. Current Selection Process

C. Final Rule

III. Public Comments on the Proposed Rule

A. Summary of Public Comments

B. Statutory and Legal Issues

C. General Support for the NPRM

D. General Opposition to the NPRM

E. H-1B Registration Requirement

1. Support for Registration Program

2. Opposition to Registration Program

3. Announcement and Length of Registration Periods

4. Required Registration Information

5. Timeline for the Implementation of the H-1B Registration Requirement

6. Fraud and Abuse Prevention for Registration Requirement

a. Suggestions Related to Fee Collection

b. Suggestions To Deter Fraud Related to Employers/Petitioners

c. Suggestions To Deter Fraud Related to Beneficiaries

7. Other Comments on H-1B Registration Program

F. Selection, Notification, and Filing of H-1B Petitions

1. Annual Cap Projections, Reserve Registrations, Registration Re-Opening

2. Notification

3. Filing Time Periods

G. Advanced Degree Exemption Allocation Amendment

1. Support for the Reversal of Selection Order

2. Opposition to the Reversal of Selection Order

3. Changed Order of Selecting Registrations or Petitions To Reach the Cap Allocations

H. Other Issues Relating to the Rule

1. Request to Extend the Comment Period

2. Miscellaneous

I. Public Comments on Statutory and Regulatory Requirements

1. Costs of the Registration Requirement

2. Benefits of the Registration Requirement

3. Labor Market Impacts on the Reversal of Selection Order

4. Other Costs and Benefits of the Reversal of Selection Order

J. Public Comments and Responses to Paperwork Reduction Act

K. Out of Scope

IV. Statutory and Regulatory Requirements

A. Executive Order 12866 and 13563

B. Regulatory Flexibility Act

C. Executive Order 13771

D. Unfunded Mandates Reform Act of 1995

E. Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act of 1996

F. Congressional Review Act

G. Executive Order 13132 (Federalism)

H. Executive Order 12988 (Civil Justice Reform)

I. National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)

J. Paperwork Reduction Act

I. Executive Summary

A. Purpose and Summary of the Regulatory Action

DHS is amending its regulations to require petitioners seeking to file H-1B cap-subject petitions, which includes petitions subject to the regular cap and those asserting eligibility for the advanced degree exemption, to first electronically register with USCIS.

This final rule also amends the process by which USCIS selects H-1B petitions toward the projected number of petitions needed to reach the regular cap and advanced degree exemption. Changing the order in which petitions are selected will likely increase the total number of petitions selected under the regular cap for H-1B beneficiaries who possess a master's or higher degree from a U.S. institution of higher education each fiscal year.

B. Legal Authority

The Secretary of Homeland Security's authority for these regulatory amendments is found in various sections of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), 8 U.S.C. 1101 et seq., and the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (HSA), Public Law 107-296, 116 Stat. 2135, 6 U.S.C. 101 et seq. General authority for issuing this final rule is found in section 103(a) of the INA, 8 U.S.C. 1103(a), which authorizes the Secretary to administer and enforce the immigration and nationality laws, as well as section 112 of the HSA, 6 U.S.C. 112, which vests all of the functions of DHS in the Secretary and authorizes the Secretary to issue regulations. Further authority for these regulatory amendments is found in:

- Section 214(a)(1) of the INA, 8 U.S.C. 1184(a)(1), which authorizes the Secretary to prescribe by regulation the terms and conditions of the admission of nonimmigrants;

- Section 214(c) of the INA, 8 U.S.C. 1184(c), which, inter alia, authorizes the Secretary to prescribe how an importing employer may petition for an H nonimmigrant worker, and the information that an importing employer must provide in the petition; and

- Section 214(g) of the INA, 8 U.S.C. 1184(g), which, inter alia, prescribes the H-1B and H-2B numerical limitations, various exceptions to those limitations, and criteria concerning the order of processing H-1B and H-2B petitions.

C. Summary of Changes From the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

Following careful consideration of public comments received, including relevant data provided by stakeholders, DHS has made a few modifications to the regulatory text proposed in the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) published in the Federal Register on December 3, 2018. See 83 FR 62406. Those changes include the following:

- Initial registration period. In the final rule, DHS is responding to a public comment by revising proposed 8 CFR 214.2(h)(8)(iii)(A)(3), a provision that identifies the initial registration period. In the NPRM, DHS proposed that USCIS would announce the start and end dates of the initial registration period on the USCIS website, but did not specify when these periods would be announced. In response to a comment suggesting that DHS include a 30-day notice requirement prior to the commencement of the initial registration period, DHS is adding that USCIS will announce the start of the initial registration period at least 30 calendar days in advance of such date. In addition, DHS will publish a notice in the Federal Register to announce the initial implementation of the H-1B registration process in advance of the cap season in which such process will be implemented.

- Limitation on requested start date. In the final rule, DHS is responding to public comment by revising proposed 8 CFR 214.2(h)(8)(iii)(A)(4), a provision that identifies when a petitioner may submit a registration during the initial registration period. In the NPRM, DHS proposed that the requested start date for the beneficiary be the first business day for the applicable fiscal year. A commenter pointed out that this requirement created a mismatch in the date requirement for cap-gap protection and the proposed date requirement for this new registration process, which could make it impossible for H-1B petitioners and beneficiaries to receive the cap-gap protections afforded by 8 CFR 214.2(f)(5)(vi). In order to correct this mismatch, DHS is removing the word “business” and revising the text to refer to the first day for the applicable fiscal year.

- Filing period. In the final rule, DHS is responding to public comments by revising proposed 8 CFR 214.2(h)(8)(iii)(D)(2), a provision that indicates the filing period for H-1B cap-subject petitions. In the NPRM, DHS proposed that the filing period will be at least 60 days. In response to public comments stating that 60 days is an insufficient amount of time for a company to gather all the necessary documentation to properly file the petition, DHS is revising the filing period to be at least 90 days.[1]

- Eligible for exemption. In this final rule, DHS is making several non-substantive changes to the regulatory text as proposed to ensure that the terminology used is consistent with the statute when describing petitions, and associated registrations, filed on behalf of those who may be eligible for exemption under section 214(g)(5)(C) of the INA, 8 U.S.C. 1184(g)(5)(C). For example, in 8 CFR 214.2(h)(8)(iii)(A)(5), DHS deleted “counted” and replaced it with “eligible for exemption.” Similar changes were made in 8 CFR 214.2(h)(8)(iii)(A)(1), (h)(8)(iii)(A)(6)(i) and (ii), (h)(8)(iii)(D), and (h)(8)(iv)(B)(1).

- Petitions determined not to be exempt. In this final rule, DHS is making non-substantive edits in 8 CFR 214.2(h)(8)(iv)(B) to clarify how USCIS may process petitions, when the registration requirement is suspended, that claim exemption from the numerical restrictions but are determined not to be exempt.

With the exception of changes discussed in this final rule, DHS is finalizing this rule as proposed.

D. Summary of Costs, Benefits, and Transfers

DHS is amending its regulations governing the process for petitions filed on behalf of cap-subject H-1B workers. Specifically, this final rule adds a registration requirement for petitioners seeking to file H-1B cap-subject petitions on behalf of foreign workers. Additionally, this final rule changes the order in which H-1B cap-subject registrations will be selected towards the applicable projections needed to meet the annual H-1B regular cap and advanced degree exemption in order to increase the odds of selection for H-1B beneficiaries who have earned a master's or higher degree from a U.S. institution of higher education.

All petitioners seeking to file an H-1B cap-subject petition will have to submit a registration, unless the registration requirement is suspended by USCIS consistent with this final rule. As required under this final rule and the registration requirement, when applicable, only those whose registrations are selected (termed “selected registrant” [2] for purposes of this analysis) will be eligible to file an H-1B cap-subject petition for those selected registrations during the associated filing period. Therefore, as selected registrants under the registration requirement, selected petitioners will incur additional opportunity costs of time to complete the electronic registration relative to the costs of completing and filing the associated H-1B petition, the latter costs being unchanged from the current H-1B petitioning process. Conversely, those who complete registrations that are unselected because of excess demand (termed “unselected registrant” for purposes of this analysis) will experience cost savings relative to the current process, as they will no longer have to complete an entire H-1B cap-subject petition that ultimately does not get selected for USCIS processing and adjudication as done by current unselected petitioners, unless the registration requirement is suspended.

To estimate the costs of the registration requirement, DHS compared the current costs associated with the H-1B petition process to the anticipated costs imposed by the additional registration requirement. DHS compared costs specifically for selected and unselected petitioners because the impact of the registration requirement to each population is not the same. Current costs to selected petitioners are the sum of filing fees associated with each H-1B cap-subject petition and the opportunity cost of time to complete all associated forms. Current costs to unselected petitioners are only the opportunity cost of time to complete forms and cost to mail the petition since USCIS returns the H-1B cap-subject petition and filing fees to unselected petitioners.

Under this final rule, when registration is required, the opportunity cost of time associated with registration will be a cost to all petitioners (selected and unselected), but those whose registrations are not selected will be relieved from the opportunity cost associated with completing and mailing the entire H-1B cap-subject petitions. Therefore, DHS estimates the costs of this rule to selected petitioners for completing an H-1B cap-subject petition as the sum of new registration costs and current costs. DHS estimates that the costs of this final rule to unselected petitioners, when registration is required, will only result from the estimated opportunity costs associated with registration. Overall, when registration is required, unselected petitioners will experience a cost savings relative to the current H-1B cap-subject petitioning process; DHS estimates these cost savings by subtracting new registration costs from current costs of preparing an H-1B cap-subject petition. These estimated quantitative cost savings will be a benefit that will accrue to only those with registrations that were not selected.

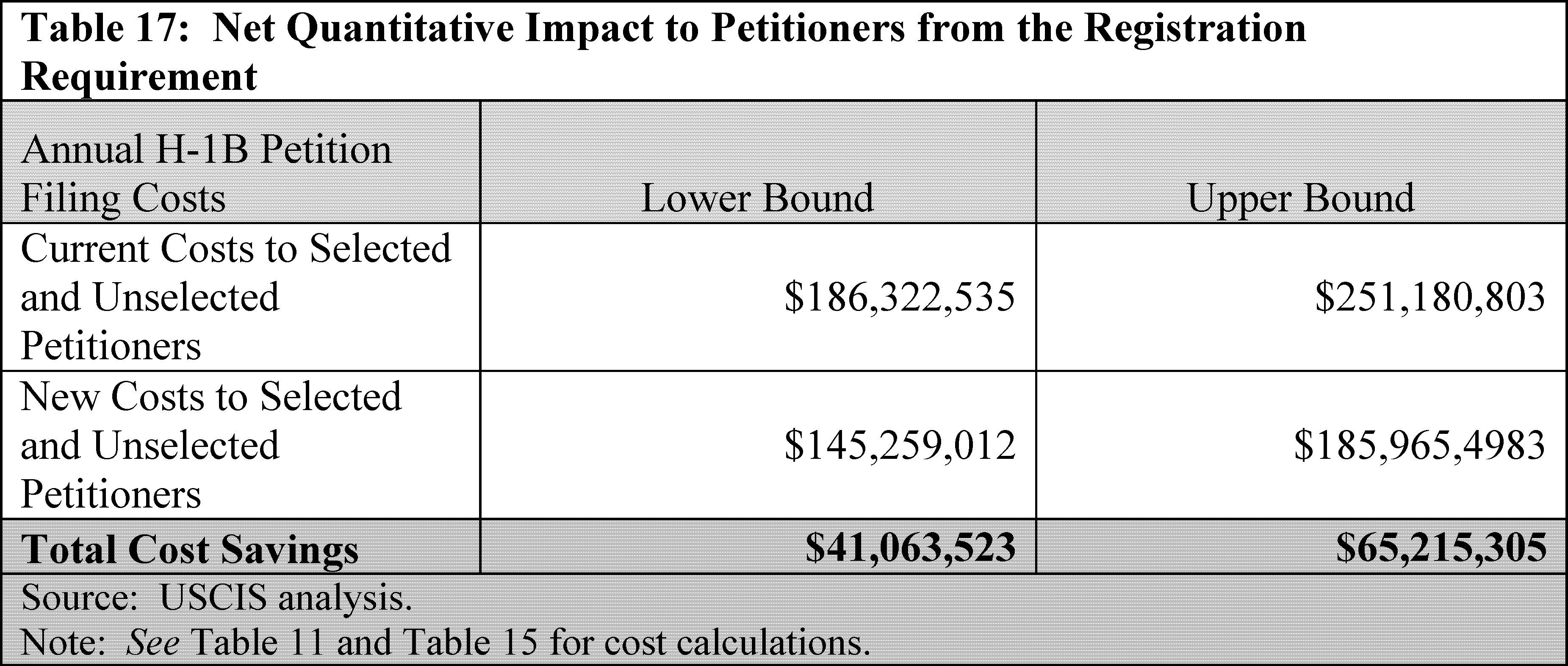

Currently, the aggregate cost for all selected petitioners to complete entire H-1B cap-subject petitions is estimated to be between $132.9 million and $165.5 million, depending on who petitioners use to prepare a petition. These current costs to complete and file an H-1B cap-subject petition are based on a 5-year petition volume average and may differ across sets of fiscal years. Current costs are not changing for selected petitioners as a result of this final rule. Rather, the registration requirement under this final rule, except when suspended, would add a new opportunity cost of time to selected petitioners who will continue to face current H-1B cap-subject petition costs. DHS estimates the added opportunity cost of time to selected petitioners to comply with the registration requirement in this final rule would range from $6.2 million to $10.3 million, again depending on who petitioners use to submit a registration and prepare a petition. Therefore, under this final rule, and when required to register, DHS estimates the adjusted aggregate total cost for all selected petitioners to complete their entire H-1B cap-subject petitions will be between $134.7 million and $171.4 million. Since these petitioners already file Form I-129, only the registration costs of $6.2 million to $10.3 million are considered new costs.

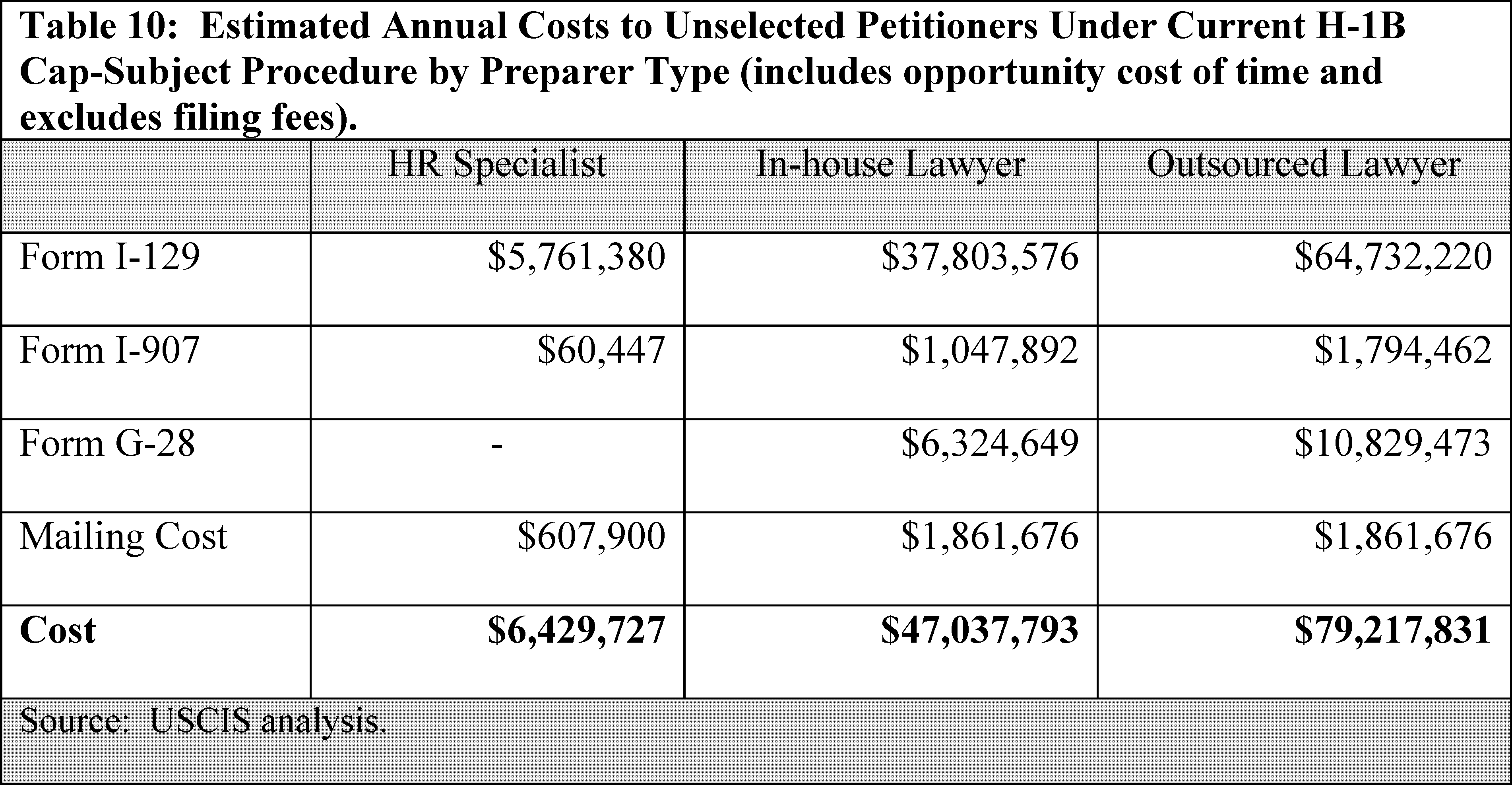

When registration is required under this final rule, unselected petitioners will experience an overall cost savings, despite new opportunity costs of time associated with the registration requirement. Currently for unselected petitioners, the total cost associated with the H-1B process is $53.5 million to $85.6 million, depending on who petitioners use to prepare the petition. The difference between total current costs for selected and unselected petitioners in an annual filing period consists of fees returned to unselected petitioners. DHS estimates the total costs to unselected petitioners for registration, when required, will range from $6.2 million to $10.1 million. DHS estimates a cost savings will occur because unselected petitioners will avoid having to file an entire H-1B cap-subject petition and only have to submit a registration, unless the registration requirement is suspended. Therefore, the difference between total current costs and total new costs for all unselected petitioners when registration is required will represent a cost savings ranging from $47.3 million to $75.5 million, again depending on who petitioners use to submit the registration.

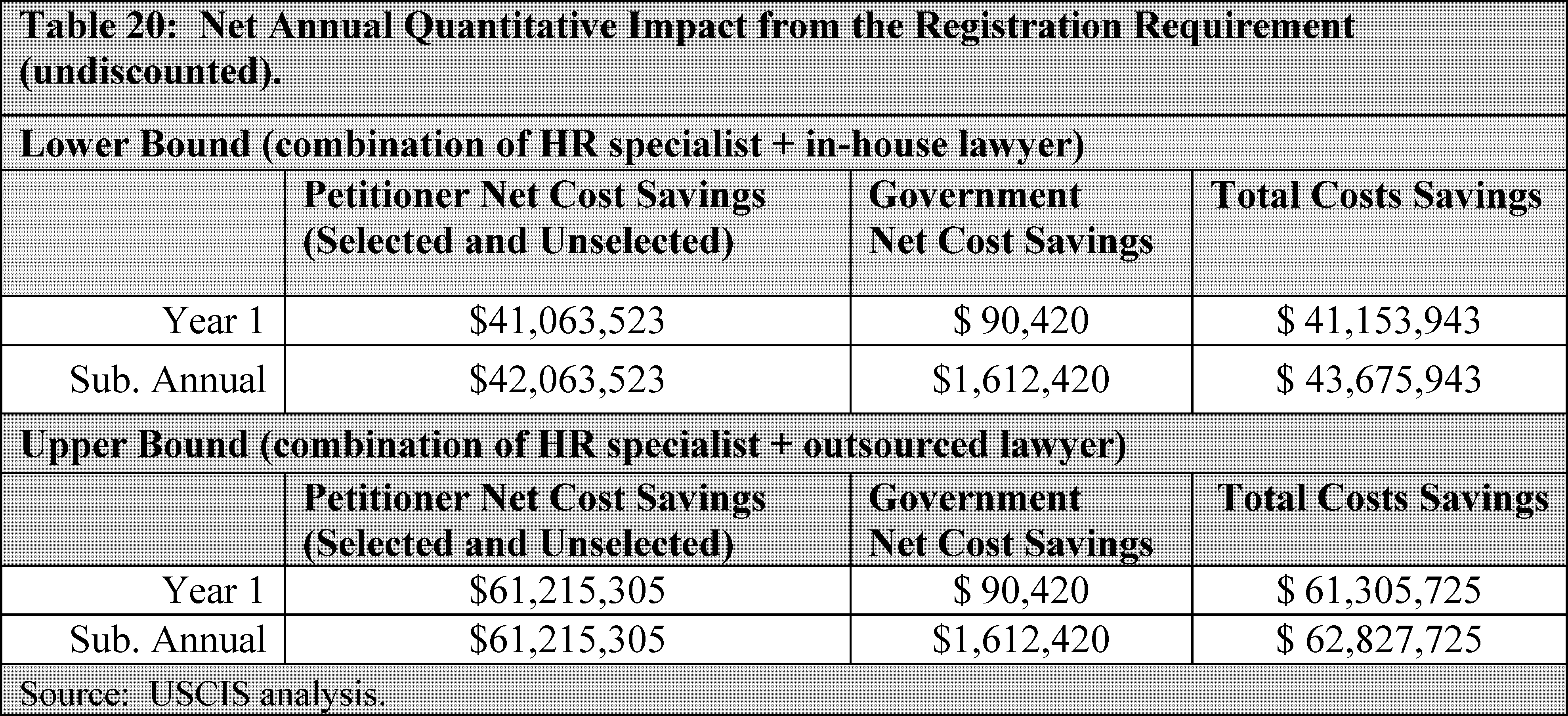

The government will also benefit from the registration requirement and process by no longer having to receive, handle, and return large numbers of petitions that are currently rejected because of excess demand (unselected petitions), except in those instances when the registration requirement is suspended. These activities will save DHS an estimated $1.6 million annually when registration is required. USCIS will, however, have to expend a total of about $1.5 million in the initial development of the registration website. This cost to the government is considered a one-time cost. DHS recognizes that there could be some additional unforeseen development and maintenance costs or costs from refining the registration system in the future. However, DHS cannot predict what these costs would be at this time and so was not able to estimate these costs. Currently there are no additional costs for annual maintenance of the servers because the registration system will be run on existing servers. Since these costs are already incurred regardless of this rulemaking, DHS did not add any estimated costs for server maintenance.

Assuming that there is no expansion in the number of registrations, the net quantitative impact of this registration requirement is an aggregate cost savings to petitioners and to government ranging from $43.4 million to $62.7 million annually. Using lower bound figures, the net quantitative impact of this registration requirement is cost savings of $434.2 million over ten years. Discounted over ten years, these cost savings would be $381.2 million based on a discount rate of 3 percent and $325.7 million based on a discount rate of 7 percent. Using upper bound figures, the net quantitative impact of this registration requirement is cost savings of $626.8 million over ten years. Discounted over ten years, these cost savings will be $550.5 million based on a discount rate of 3 percent and $470.6 million based on a discount rate of 7 percent.

DHS notes that these overall cost savings result only in years when registration is required and the demand for registrations and the subsequently filed petitions exceeds the number of available visas needed to meet the regular cap and the advanced degree exemption. For years where DHS has demand that is less than the number of available visas, this registration requirement would result in increased costs. For this final rule to result in net quantitative cost savings, at least 110,182 petitions (registrations and subsequently filed petitions under the final rule, unless the registration requirement is suspended) will need to be received by USCIS based on lower bound cost estimates. For upper bound cost estimates, USCIS will need to receive at least 111,137 registrations and subsequently filed petitions for this rule to result in net quantitative cost savings.

The change to the petition selection process under this final rule could result in greater numbers of highly educated workers with degrees from U.S. institutions of higher education entering the U.S. workforce under the H-1B program. USCIS estimates that the change will result in an increase in the number of H-1B beneficiaries with a master's degree or higher from a U.S. institution of higher education selected by 16 percent (or 5,340 workers each year). If there is an increase in the number of H-1B beneficiaries with a master's degree or higher from a U.S. institution of higher education, wage transfers may occur. These transfers would be borne by companies whose petitions, filed for beneficiaries who are not eligible for the advanced degree exemption (e.g. holders of bachelors degrees and holders of advanced degrees from foreign institutions of higher education), might have been selected and ultimately approved but for the reversal of the selection order.

This final rule will also allow for the H-1B cap and advanced degree exemption selections to take place in the event that the registration system is inoperable for any reason and needs to be suspended. If temporary suspension of the registration system is necessary, then the costs and benefits described in this analysis resulting from registration for the petitioners and government will not apply during any period of temporary suspension. However, the reverse selection order will still take place and is anticipated to yield a higher proportion of H-1B beneficiaries with a master's degree or higher from a U.S. institution of higher education being selected.

E. Effective Date

This final rule will be effective on April 1, 2019, 60 days from the date of publication in the Federal Register.

F. Implementation

The changes in this final rule will apply to all Form I-129 H-1B cap-petitions, including those for the advanced degree exemption, filed on or after the effective date of the final rule. The treatment of Form I-129 H-1B cap-petitions filed prior to the effective date of this final rule will be based on the regulatory requirements in place at the time the petition is properly filed. DHS has determined that this manner of implementation best balances operational considerations with fairness to the public.

USCIS will be suspending the registration requirement until it can complete all requisite user testing of the new H-1B registration system and otherwise ensures the system and process are fully operable, and addresses concerns raised by commenters in response to the proposed rule. DHS will publish a notice in the Federal Register to announce the initial implementation of the registration process in advance of the H-1B cap season in which the registration process will be first implemented. USCIS will also engage in stakeholder outreach and provide training to the regulated public on the registration system in advance of its implementation. Consistent with this final rule, USCIS will formally announce the temporary suspension of the registration requirement for FY 2020 on the USCIS website following the effective date of the final rule.

II. Background

A. The H-1B Visa Program and Numerical Cap and Exemptions

The H-1B visa program allows U.S. employers to temporarily hire foreign workers to perform services in a specialty occupation, services related to a Department of Defense (DOD) cooperative research and development project or coproduction project, or services of distinguished merit and ability in the field of fashion modeling. See INA 101(a)(15)(H)(i)(b), 8 U.S.C. 1101(a)(15)(H)(i)(b); Public Law 101-649, section 222(a)(2), 104 Stat. 4978 (Nov. 29, 1990); 8 CFR 214.2(h). A specialty occupation is defined as an occupation that requires (1) theoretical and practical application of a body of highly specialized knowledge and (2) the attainment of a bachelor's or higher degree in the specific specialty (or its equivalent) as a minimum qualification for entry into the occupation in the United States. See INA 214(i)(l), 8 U.S.C. 1184(i)(l).

Congress has established limits on the number of workers who may be granted initial H-1B nonimmigrant visas or status each fiscal year (commonly known as the “cap”). See INA section 214(g), 8 U.S.C. 1184(g). The total number of workers who may be granted initial H-1B nonimmigrant status during any fiscal year currently may not exceed 65,000. See INA section 214(g), 8 U.S.C. 1184(g). Certain petitions are exempt from the 65,000 numerical limitation. See INA section 214(g)(5) and (7), 8 U.S.C. 1184(g)(5) and (7). The annual exemption from the 65,000 cap for H-1B workers for those who have earned a qualifying U.S. master's or higher degree may not exceed 20,000 workers.[3] See INA section 214(g)(5)(C), 8 U.S.C. 1184(g)(5)(C).

B. Current Selection Process

Under the current H-1B cap filing and selection process, USCIS monitors the number of H-1B petitions it receives at each service center in order to manage the H-1B allocations. Petitioners may file H-1B petitions as early as six months ahead of the actual date of need (commonly referred to as the employment start date). See 8 CFR 214.2(h)(9)(i)(B). Because of this, USCIS routinely receives hundreds of thousands of H-1B petitions in early April each year (for visas allocated for the following fiscal year) and this period is informally recognized as an H-1B “cap season.” Currently, USCIS monitors the number of H-1B cap-subject petitions received and notifies the public of the date that USCIS received a sufficient number of petitions needed to reach the numerical limit (the “final receipt date”). See 8 CFR 214.2(h)(8)(ii)(B). USCIS then may randomly select from the cap-subject petitions received on the final receipt date the projected number of petitions needed to reach the limit.

If USCIS receives sufficient H-1B petitions to reach the projected number of petitions to meet both the regular cap and the advanced degree exemption for the upcoming fiscal year within the first five business days, USCIS first randomly selects H-1B petitions subject to the advanced degree exemption. Id. Once the random selection process for the advanced degree exemption is complete, USCIS then conducts the random selection process for the regular cap, which includes the remaining unselected petitions filed for, but not selected in, the advanced degree exemption. Once the random selection process for the regular cap is complete, USCIS rejects all remaining H-1B cap-subject petitions not selected during one of the random selections. See 8 CFR 214.2(h)(8)(ii)(D).

C. Final Rule

Following careful consideration of public comments received, DHS has made a few modifications to the regulatory text proposed in the NPRM (as described above in Section I.C.). The rationale for the proposed rule and the reasoning provided in the background section of that rule remain valid with respect to these regulatory amendments. Section III of this final rule includes a detailed summary and analysis of public comments that are pertinent to the proposed rule and DHS's role in administering the Registration Requirement for Petitioners Seeking To File H-1B Petitions on Behalf of Cap-Subject Aliens. A brief summary of comments deemed by DHS to be out of scope or unrelated to this rulemaking, making a detailed substantive response unnecessary, is provided in Section III.J. Comments may be reviewed at the Federal Docket Management System (FDMS) at http://www.regulations.gov, docket number USCIS-2008-0014.

III. Public Comments on the Proposed Rule

A. Summary of Public Comments

In response to the proposed rule, DHS received 817 comments during the 30-day public comment period. Of these, 11 comments were duplicate submissions and approximately 321 were letters submitted through mass mailing campaigns. DHS considered all of these comment submissions. Commenters consisted of individuals (including U.S. workers), law firms, labor organizations, professional organizations, advocacy groups, nonprofit organizations, and representatives from State and local governments. Some commenters expressed support for the rule and/or offered suggestions for improvement. Of the commenters opposing the rule, many commenters expressed opposition to a part of or all of the proposed rule. Some just expressed general opposition to the rule without suggestions for improvement. For many of the public comments, DHS could not ascertain whether the commenter supported or opposed the proposed rule. A number of comments received addressed subjects beyond those covered by the proposed rule, and were deemed out of scope.

DHS has reviewed all of the public comments received in response to the proposed rule and is addressing relevant comments in this final rule.[4] DHS's responses are grouped by subject area, with a focus on the most common issues and suggestions raised by commenters. DHS is not addressing comments seeking changes in U.S. laws, regulations, or agency policies that are out of scope and unrelated to the changes to 8 CFR part 214 it proposed in the NPRM.

B. Statutory and Legal Issues

Comment: A few commenters stated that the proposed reversal of selection order was within USCIS's congressional authority under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). For example, a company commented that reordering the lottery is within the reasonable discretion of the Department under the INA. The commenter argued that ambiguity and silence in the statute is properly read as Congressional delegation to DHS and USCIS to construct a reasonable H-1B allocation process.

Response: DHS agrees with the commenter that the reversal of the selection order is permissible based on the general authority provided to DHS under sections 103(a), 214(a) and (c) of the INA, 8 U.S.C. 1103, 1184(a) and (c), and section 112 of the HSA, 6 U.S.C. 112. As discussed in more detail in response to the next comment, DHS also agrees that the statute is not clear as to how the numerical allocations must be counted, and that reversal of the selection order is a reasonable interpretation of ambiguous statutory text.

Comment: Many commenters, including companies, attorneys, professional associations, and trade associations, questioned whether USCIS has the statutory authority to reverse the selection order. Some commenters stated changes to the cap and selection order can only be made through Congress. A form letter campaign and other commenters argued that existing law clearly indicates individuals with a U.S. master's degree or higher are not subject to the H-1B cap until after 20,000 exempted visas are issued. Many commenters referenced the statutory language in 8 U.S.C. 1184(g)(5) as the basis for their argument that USCIS may lack the statutory authority to conduct the general visa lottery for the 65,000 H-1B visas prior to the lottery for the 20,000 U.S. master's degree petitions that are exempt from the general lottery. For example, an attorney argued that under 8 U.S.C. 1184(g)(5), a U.S. master's degree holder cannot be considered under the regular cap of 65,000 visas until the master's allocation of 20,000 has first been extinguished. Another commenter argued that USCIS is misinterpreting its authority as granted by Congress. The commenter stated that Congress did not mandate an additional 20,000 visas be granted to beneficiaries with a U.S. advanced degree, but rather that up to 20,000 beneficiaries with a U.S. advanced degree would be considered cap-exempt annually. The commenter asserted that any effort to subject a beneficiary with a U.S. advanced degree to the annual regular H-1B cap before the advanced degree visas are allocated is beyond the authority Congress has granted USCIS. In addition, the commenter asserted that the proposed selection method also fails to account for variations in filing levels. Specifically, in years when insufficient filings are made to exhaust the advanced degree exemption allocation, the selection process described could allocate cap visas to advanced degree applicants who would otherwise be considered cap-exempt, thus leaving cap-exemptions available and unused for beneficiaries with a U.S. advanced degree. The proposal also would potentially reserve remaining visas for beneficiaries with a U.S. advanced degree even if their employer filed the petition after an employer filing for a beneficiary who does not have a U.S. advanced degree, which the commenter asserted is also in violation of Congress' directive that visas be allocated to petitions in the order received. A trade association requested that USCIS provide a more robust legal explanation to justify how its proposed changes to the counting of visas is not only consistent with Congress' intentions, but also Congress' action in creating 8 U.S.C. 1184(g)(5)(C).

Response: DHS believes that changing the order in which registrations or petitions, as applicable, are selected will result in a selection process that is a reasonable interpretation of the statute and more consistent with the purpose of the advanced degree exemption.

The statute is ambiguous as to the precise manner by which beneficiaries with a master's or higher degree from a U.S. institution of higher education must be counted toward the numerical allocations. The statute states that the 65,000 numerical limitation does not apply until 20,000 qualifying beneficiaries are exempted, but is otherwise silent as to whether they must be exempted prior to, concurrently with, or subsequent to the 65,000 numerical limitation being counted and/or reached, or some combination thereof. This ambiguity was recognized by DHS when it initially determined how the exemption should be administered.[5] According to INA sec. 214(g)(5)(C), 8 U.S.C. 1184(g)(5)(C), “The numerical limitations contained in paragraph (1)(A) shall not apply to any nonimmigrant alien issued a visa or otherwise provided status under section 1101(a)(15)(H)(i)(b) of this title who . . . has earned a master's or higher degree from a United States institution of higher education (as defined in section 1001(a) of Title 20) until the number of aliens who are exempted from such numerical limitation during such year exceeds 20,000.” The numerical limitation of paragraph (1)(A) provides the total number of aliens who may be issued an H-1B visa or otherwise provided H-1B status. The numerical limitation, once it has been reached, means that no additional aliens, beyond the 65,000 limit, may be issued an initial H-1B visa or otherwise provided H-1B status unless they are exempt from the numerical limitation. A limited basis for exemption from the numerical limitation, for petitioners who are otherwise subject to the cap, is provided in INA sec. 214(g)(5)(C), 8 U.S.C. 1184(g)(5)(C), for beneficiaries who have earned a master's or higher degree from a U.S. institution of higher education, until the number of such aliens exempted exceeds 20,000. This final rule, therefore, implements a process for counting petitions towards the numerical allocations in a manner that reasonably interprets the statute. DHS believes this approach is most consistent with the overall statutory framework as it counts all petitions filed by cap-subject petitioners until the numerical limitation is reached, and once that numerical limitation is reached, and otherwise precludes additional petitions, allows for an additional 20,000 petitions consistent with INA sec. 214(g)(5)(C), 8 U.S.C. 1184(g)(5)(C).

DHS also disagrees with the assertion that the selection order as proposed in the NPRM and as set forth in this final rule fails to account for variations in filing levels. DHS notes that the H-1B numerical limitation has been met before the end of the applicable fiscal year in each year since 1997.[6] USCIS has also received a sufficient number of petitions to reach the numerically limited exemption under INA sec. 214(g)(5)(C), 8 U.S.C. 1184(g)(5)(C) in each year from FY 2008 through FY 2019. While DHS recognizes that it is theoretically possible that a high rate of selection of submissions eligible for the advance degree exemption under the H-1B regular cap could result in an insufficient number of remaining submissions to meet the projected number needed to reach the advance degree exemption at the end of the annual initial registration period, the result is that USCIS would continue to allow for submissions through the end of the applicable fiscal year or until such time as USCIS has received enough registrations or petitions, as applicable, to meet the projected number need to reach the numerically limited cap exemption. DHS believes that historical filing rates indicate that such an occurrence (i.e. failing to receive enough registrations or petitions to meet the advanced degree exemption) is unlikely to happen at the current numerical allocation amounts. Rather, historical filing rates indicate that USCIS will continue to receive an excess number of H-1B filings to meet the numerical allocations. Further, reversing the selection order, such that all submissions are counted toward the projected number needed to reach the numerical limitation first, and then counting the remaining submissions, if eligible, towards the numerically limited cap exemption, ensures that the chance for selection under the regular cap for beneficiaries with a master's or higher degree from a U.S. institution of higher education is not reduced by the order of selection, as discussed in section IV.A.4.b. of this rule. DHS believes that administering the numerically limited cap exemption in a way that does not reduce the odds of selection for beneficiaries with a U.S. advanced degree under the regular cap is most appropriate and maximizes the overall odds of selection for such beneficiaries under the numerical allocations. Doing so also outweighs the potential that H-1B demand might decrease so significantly from that experienced over the course of the last decade to a level where both numerical allocations are not met by the end of the applicable fiscal year.

DHS also disagrees that the statute requires that initial H-1B visas be allocated to petitions in the order received. The statute states that aliens subject to the H-1B cap shall be issued visas or otherwise provided status in the order in which petitions are filed. This statutory provision, and more specifically the term “filed” as used in INA 214(g)(3), 8 U.S.C. 1184(g)(3), is ambiguous.[7] Further, a literal application of this statutory language would lead to an absurd result. The Department of State (“DOS”) does not issue H-1B visas, and USCIS does not otherwise provide H-1B status, based on the order in which petitions are filed. Such a literal application would necessarily mean that processing delays pertaining to a petition earlier in the petition filing order would preclude issuance of a visa or provision of status to all other H-1B petitions later in the petition filing order. The longstanding approach to implementing the numerical limitation has been to project the number of petitions needed to reach the numerical limitation. Under this final rule, USCIS will continue to count submissions towards the projected number needed to generate a sufficient number of petition approvals to reach the numerical limitation but without exceeding the numerical limitation. DHS is not changing the approach to administering the numerical allocations as it relates to the use of projections. As such, under this final rule, unless the requirement is suspended, petitioners will be required to register and USCIS will select a sufficient number of registrations projected as needed to reach the numerical allocations. Only those petitioners with selected registrations will be eligible to file. Once filed, petitions will generally be processed in the order in which they are filed.

Comment: A commenter challenged the proposed changes in the cap allocation selection order as contrary to the Congressional intent for the H-1B visa classification. The commenter, relying on general legislative history for the H-1B program, noted that Congress did not intend that H-1B visas be given on a “preferential basis to the most skilled and highest-paid petition beneficiaries,” and that “Congress has never limited use of H-1B visas to the best and brightest.” The commenter indicated that DHS should ignore E.O. 13788 to the “extent it mandates preference for the `best and the brightest' among H-1B applicants” and said that the “President lacks the authority, through his executive agencies, to implement a change in law that is contrary to legislative intent.”

Response: DHS disagrees with the commenter's views that Congressional intent and legislative history preclude the changes DHS is making to the cap allocation selection order. While DHS agrees that Congress has not limited the H-1B classification to the “best and brightest” foreign nationals, nothing in the statute or legislative history precludes DHS from administering the cap allocation in a way that increases the odds of selection for beneficiaries with a master's or higher degree from a U.S. institution of higher education. As discussed elsewhere in this final rule, DHS is reversing the cap selection order to prioritize beneficiaries with a master's or higher degree from a U.S. institution of higher education in accordance with congressional intent, as the numerically limited exemption from the cap for these beneficiaries was created by Congress and appears in the INA. The reversal of the selection order is permissible based on the general authority provided to DHS under sections 103(a), 214(a) and (c) of the INA, 8 U.S.C. 1103, 1184(a) and (c), and section 112 of the HSA, 6 U.S.C. 112. DHS believes that reversing the cap selection order is consistent with E.O. 13788, which instructs DHS to “suggest reforms to help ensure that H-1B visas are awarded to the most-skilled or highest-paid petition beneficiaries.” The reversal of the selection order will likely have the effect of increasing the total percentage of master's degree holders in the H-1B population. In the aggregate, master's degree holders will tend to be more skilled and earn higher wages. Contrary to the commenter's assertion, this final rule does not limit eligibility for the H-1B classification to the “best and the brightest.”

Comment: Some commenters said the proposed selection method would violate the requirement in 8 U.S.C. 1184(g) to process H-1B petitions in the order they are received. A professional association commented that when describing its authority for the proposed rule USCIS had failed to reference 8 U.S.C. 1184(g)(3), which states that cap-subject H-1B nonimmigrants “shall be issued visas (or otherwise provided nonimmigrant status) in the order in which petitions are filed . . . ” The commenter concluded that the proposed H-1B registration system, which would mandate selection of “registrations” over “petitions,” is arguably unlawful. An individual commenter argued the use of a lottery selection process violates the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) at 8 U.S.C. 1184(g)(3), which states that aliens who are subject to the numerical limitations shall be issued visas “in the order in which petitions are filed.” Moreover, the commenter stated that the numerical limit refers to the number of visas and status, not the number of petitions. An individual commenter similarly stated that the proposed system would violate this provision because employers would not be able file a petition unless they have registered and been selected through the registration process. A law institute commented that the use of the new selection process in years when there is no lottery appears to be in excess of DHS' authority and that DHS should either provide a sufficient legal justification for changing how visas are counted in years where there is no lottery or not use this process in such years.

Response: DHS disagrees with the commenter's assertions. The use of a random selection process has been found to not violate INA 214(g)(3), 8 U.S.C. 1184(g)(3). See Walker Macy v. USCIS, 243 F.Supp.3d 1156, 1163 (D. Or. 2017). Further, DHS believes that a similar approach to selection of registrations, whereby USCIS will randomly select registrations submitted electronically over a designated period of time to ensure the fair and orderly administration of the numerical allocations, is defensible under the general authority provided to DHS in INA 214(a), 8 U.S.C. 1184(a).

DHS also disagrees with the commenter's assertion that use of the new selection process in years of low demand is in excess of DHS' authority. As stated, DHS is relying on its general authority to implement the registration process as an antecedent procedural requirement that must be met before a petition is deemed to be properly filed. See INA 103(a), 214(a) and (c)(1), 8 U.S.C. 1103(a), 1184(a) and (c)(1). In years where demand is low, and an insufficient number of registrations have been received during the annual initial registration period to meet the number projected as needed to reach the regular H-1B cap, USCIS would select all of the registrations properly submitted during the initial registration period and notify all of the registrants that they may proceed with the filing of the H-1B cap petition. Once H-1B petitions have been properly filed, USCIS would generally process the petitions in the order that they have been filed. Registrations submitted after the initial registration period would continue to be selected on a rolling basis until such time as a sufficient number of registrations have been received. To ensure fairness, USCIS may randomly select from among the registrations received on the final registration date a sufficient number to reach the projected number. Contrary to the commenter's assertion, DHS is not changing the way visas are counted, but is merely using its general authority to create a more efficient process for administering the H-1B numerical allocations but otherwise continuing the historical use of projections to estimate the number of petition approvals that will likely be needed to reach, but not exceed, the H-1B numerical limitations. As stated in response to similar comments, a literal application of the statutory language in INA 214(g)(3), 8 U.S.C. 1184(g)(3), as the commenter suggests, would lead to an absurd result. DOS does not issue H-1B visas, and USCIS does not otherwise provide H-1B status, based on the order in which petitions are filed. Such a literal application would necessarily mean that processing delays pertaining to a petition earlier in the petition filing order would preclude issuance of a visa or provision of status to all other H-1B petitions later in the petition filing order.

Comment: An individual commenter argued that the use of a lottery selection process is not inconsistent with 8 U.S.C. 1184(g)(5), and that arguments to the contrary are incorrect.

Response: DHS agrees with the commenter's assertions that the use of a random selection process is not inconsistent with the existing statute and is a reasonable manner in which to administer the numerical limitations as it ensures that the allocations can be administered in a fair and efficient manner given the excess demand experienced each year for H-1B visas.

C. General Support for the NPRM

Comment: Some commenters expressed general support for the regulation. A few of these commenters stated that the rule should be implemented in time for the upcoming H-1B cap filing season. Other commenters offered additional non-substantive rationale for their support of the rule including: It would help track visas and prevent overstay issues; it would eliminate fraudulent H-1B filings and allow for the best candidates to obtain visas; it would cause an increase in U.S. wages; it would stop visa abuse and flooding of applications by certain companies; it would prioritize students studying in the United States and increase their chances to stay and work in the U.S.; and it would streamline the H-1B cap-petition process.

Response: DHS agrees with the commenters that this rule will streamline the H-1B cap selection process and will increase the likelihood of retaining beneficiaries in the United States who have earned a master's or higher degree from a U.S. institution of higher education. An increase in the overall percentage of H-1B aliens with a master's or higher degree from a U.S. institution of higher education could increase wages assuming that beneficiaries with bachelor's degrees, advanced degrees from U.S. for-profit universities or foreign advanced degrees are paid less than and replaced by beneficiaries with master's or higher degrees from U.S. institutions of higher education. DHS, however, will be suspending the registration requirement for the FY 2020 H-1B cap in order to further test the system. As such, the efficiency gains DHS anticipates will result from the streamlined cap selection process will not be realized until the registration requirement applies and registration prior to the filing of an H-1B cap-petition is required. DHS anticipates that this will occur starting with the FY 2021 H-1B cap.

DHS disagrees with the commenters' assertions that this rule will help to track visas, prevent H-1B nonimmigrants from staying beyond their authorized period of stay, or eliminate fraudulent H-1B petitions. This final rule simply provides for a registration requirement for H-1B cap-petitioners and reverses the order in which USCIS counts submissions toward the annual H-1B numerical allocations. Additional changes to strengthen the H-1B program and prevent fraud and abuse are outside the scope of this final rule.

D. General Opposition to the NPRM

Comment: A few commenters expressed general opposition to the regulation and criticized the H-1B program, arguing it prioritizes low-cost foreign workers over American workers. Some commenters suggested suspending the H-1B program, and a few commenters stated the rule is not merit-based. Some commenters also argued the rule does not do enough to prevent outsourcing, and fraud issues. Another commenter remarked that the rule needed input from lawyers and affected U.S. employers before implementation.

Response: DHS believes that this final rule is merit-based in that it will likely increase the number of beneficiaries with a master's or higher degree from a U.S. institution of higher education to be selected for further processing under the H-1B allocations. DHS disagrees that this rule prioritizes foreign workers. Rather, this final rule simply creates a registration process to streamline the existing H-1B cap selection process, and reverses the order in which submissions are counted toward the H-1B numerical allocations, but does not change the overall number of foreign workers that may be hired under existing statutory authority. Moreover, DHS does not have the statutory authority to suspend the H-1B program. Additional changes to strengthen the H-1B program and prevent fraud and abuse are outside the scope of this final rule but will indeed be pursued in a separate notice of proposed rulemaking. DHS disagrees with the commenter's assertion that implementation should not occur until input has been received from lawyers and affected U.S. employers. Among the commenters, DHS was able to identify numerous lawyers and affected U.S. companies, as well as trade associations, who submitted comments on the proposed rule and DHS has carefully considered their input in this rulemaking. DHS, however, will issue a notice in the Federal Register prior to implementation of the registration requirement to provide advance notice to affected stakeholders of the implementation of the registration requirement. This notice, however, would just pertain to the initial implementation of the registration requirement. Once implemented, further details will be provided on the USCIS website consistent with this final rule.

E. H-1B Registration Requirement

1. Support for Registration Program

Comment: Several commenters expressed support for the registration requirement. A few commenters stated the electronic registration process will be easier and more cost-effective. An attorney stated that the proposed system was an improvement as it would reduce waste and increase efficiency. Another commenter asserted that the registration process would relieve uncertainty for employers and employees, and mitigate burdens on USCIS.

Response: DHS agrees with the commenters. The registration process, once implemented, will provide petitioners and USCIS with a more efficient and cost-effective way to administer the H-1B cap selection process, and should reduce some of the uncertainty in the petitioning process.

2. Opposition to Registration Program

Comment: An individual commenter stated that the proposed rule would make it easier for employers to file H-1B petitions and hire foreign workers, which is not in line with the Administration's “Hire American, Buy American[sic]” agenda.

Response: This rule is consistent with the goals of Executive Order 13788, Buy American and Hire American, and therefore DHS disagrees with the commenter. This final rule does not alter the substantive requirements for the H-1B nonimmigrant classification, and thus does not make it “easier” to hire foreign workers. The registration process, once implemented, will be a more efficient process for administering the H-1B numerical allocations than the system that is currently in place. Increased governmental efficiency does not conflict with the Buy American and Hire American Executive Order. Further, the reversal of the cap selection order is expected to result in a greater number of beneficiaries with a master's or higher degree from a U.S. institution of higher education being selected and is therefore in line with the executive order's directive to “help ensure that H-1B visas are awarded to the most-skilled or highest-paid petition beneficiaries.”

3. Announcement and Length of Registration Periods

Comment: An individual commenter who supported the rule said it is unclear whether the cut-off time for registration will be announced up-front (e.g., few days earlier). A company stated that the proposed rule introduced uncertainties that must be clarified with specificity, and submitted a list of procedural uncertainties about the proposed registration system. An advocacy group stated that aspects of the new registration system would create timing issues, for which it requested that USCIS issue clarifications. The group asked for clarification regarding:

- The registration count and whether it would always be completed by the end of March and when notification to selected registrants would be provided.

- How frequently the agency will check registration numbers and petition filing numbers and on what dates each year.

- Whether the agency will notify the public as to the number of registrations and associated petitions that have been filed.

- How much advance notice will be provided concerning any reopening of registration.

- How much advance notice will be given concerning the availability of H-1B numbers allowing further selected registrants during a fiscal year, beyond the initial selection of registrations.

Response: USCIS will announce the start date of the initial registration period on the USCIS website for each fiscal year at least 30 days in advance of the opening of the registration period. In each fiscal year, the registration period will begin at least 14 calendar days before the first day of petition filing and will last at least 14 calendar days. USCIS will also separately announce the final registration date in any fiscal year on the USCIS website. If USCIS determines that it is necessary to keep the registration period open at the end of the initial registration period, the final registration date will be determined once USCIS has received the number of registrations projected as needed. USCIS, however, will not be able to identify the final registration date in advance as the date would be contingent on the number of registrations received. Similarly, if USCIS determines that it is necessary to re-open the registration period, it will announce the start of the re-opened registration period on its website before the start of the re-opened registration period. See 8 CFR 214.2(h)(8)(iii)(A)(7). USCIS, however, will not be able to identify the final registration date for the re-opened registration period as that date would also be contingent on the number of registrations received.

Comment: Several commenters, including a form letter campaign, stated that USCIS should not be able to announce changes to the program on its website. The commenters asserted this could disrupt the H-1B planning process for businesses, notably smaller companies who do not have the resources to make such changes quickly. Similarly, an attorney stated that the applicable statute and law do not permit USCIS to make announcements on its website substantially changing the way the lottery is run each year so that “applications would need to be filed again”.

Response: DHS disagrees that making announcements consistent with established regulatory procedure that is being codified through notice and comment rulemaking constitutes making changes (substantive or procedural) to the program. In this rule DHS is codifying the procedure it will use to announce pertinent information regarding the H-1B cap process in the Code of Federal Regulations, and is simultaneously announcing and explaining these procedures in the Federal Register publication of this final rule. The regulations codified therein explicitly identify the USCIS website as the source of this type of information in the future. DHS believes that authorizing USCIS to post H-1B cap related announcements on the USCIS website is consistent with the way in which USCIS has historically communicated with the regulated public about the H-1B cap allocations and provides a timely and efficient method of communication of program-related information to the public as well as transparency. The public frequently turns to the USCIS website for information and routinely uses the USCIS website for general information on immigration benefits, rules, and processes; applicable statutes and regulations; downloadable immigration forms; specific case status information; and processing times at the various Service Centers and district offices. USCIS currently notifies the public when it will begin accepting petitions subject to the cap for a given fiscal year and when numerical limits have been reached through its website. USCIS has historically and also would currently use its website to inform the public of potential re-opening of the cap filing period. Maintaining this practice therefore would be consistent with settled expectations and USCIS' existing legal authority. If USCIS does in the future determine that it is necessary to suspend the registration process, USCIS will make the announcement on its website as soon as practicable, and will take into consideration the possibility that the opening of the petition filing season may need to be temporarily delayed to allow sufficient time for the preparation and orderly filing of H-1B cap-subject petitions.

Comment: A trade association noted that no advance notice requirement language is included in the proposed regulatory text. The commenter stated that the 30-day notice prior to the commencement of the initial registration period must be codified in the proposed 8 CFR 214.2(h)(iii)(8)(A)(3), reasoning that without the inclusion of this language, USCIS could announce the initial registration on the day the agency would begin receiving registrations.

Response: DHS thanks the commenter for noting the absence of the 30-day minimum timeframe and has made edits in this final rule to the regulatory text as proposed to ensure that the regulated public is provided with at least 30 days advance notice of the first date of the initial registration period. DHS disagrees, however, that 30-days advance notice should be required prior to re-opening the registration period consistent with this final rule. DHS believes that 30-days advance notice prior to re-opening the registration period is unnecessary and could undermine USCIS's ability to select additional registrations and invite additional petitions in a timely manner, thereby frustrating the purpose of re-opening the registration period. Even though 30-days advance notice will not be provided when USCIS re-opens the registration period, USCIS will ensure that the announcement of the reopening of the registration period in any fiscal year is made as early as practicable to afford maximum advance notice to the regulated public.

Comment: Many commenters, including trade associations, a university, a law firm, and individuals expressed concern that the proposed duration of the registration period would be too short. A law firm requested that the registration period be open for at least 30 days, arguing that the proposed 14-day initial registration period is insufficient time for law firms to review a potentially large volume of cases. A form letter campaign suggested 60-day advance notice and a 30-day registration period. An individual commenter recommended a 45-day advance notice and a 30-day registration period. A trade association recommended a 30-day registration period beginning on a scheduled start date announced no later than January 15 each year.

Response: The annual initial registration period will last for a minimum period of 14 calendar days, but where practicable USCIS will provide more time. See 8 CFR 214.2(h)(8)(iii)(A)(3). DHS believes that 14 calendar days is a sufficient amount of time to complete the registration process. The registration does not require extensive information and will not take a lot of time for completion and submission. Additionally, USCIS will provide at least 30 days advance notice of the opening of the initial annual registration period for the upcoming fiscal year via the USCIS website (www.uscis.gov). USCIS will conduct stakeholder outreach prior to the initial implementation of the registration system to allow stakeholders the opportunity to familiarize themselves with the electronic registration process. DHS notes that the 30-day period of advance notice of the opening of the initial registration period is the minimum amount of time that USCIS must provide, but USCIS is not precluded from providing notice more than 30 days in advance if USCIS determines that additional notice is needed to adjust to circumstances at that time. DHS believes the minimum 30 days advance notice will give petitioners sufficient time to prepare registrations given that, once registration is required and implemented, there should be a settled expectation that registration will be required, unless suspended, and most employers or attorneys will have already begun to identify H-1B beneficiaries for the upcoming cap by the time that the announcement is made such that additional preparation to submit registrations should not be overly burdensome.

4. Required Registration Information

Comment: A professional services company, multiple business associations, multiple law firms, and an individual commenter said it would be helpful to have a Petitioner account so that petitioners do not have to enter their corporate information for every single beneficiary. A business association said that petitioners should be allowed to submit all of its beneficiaries via a bulk submission process, and that DHS use audits to detect patterns of abuse. An individual commenter requested that USCIS provide a tool for beneficiaries to view their status.

Response: As noted, USCIS will be suspending the registration requirement for the FY 2020 cap season (beginning April 1, 2019) to complete all requisite user testing of the new H-1B registration system and otherwise ensure the system and process are operable. As the testing continues, USCIS is exploring a number of options for efficient operation, use, and maintenance of the system. USCIS will not require petitioners to enter their corporate information for every beneficiary.

Comment: A business association said that the required registration information specifically enumerated in the preamble is sufficient, and that the regulatory text should be revised to remove the `catch-all' line referring to `any additional basic information requested by the registration system' to promote certainty. A company also suggested that the reference to `any additional basic information' would cause uncertainty, and requested that USCIS provide 90 days' notice of updates to required information prior to the registration period. An advocacy group said that USCIS should not be able to change registration prerequisites, and that USCIS should publish the form that will be used and allow public comment on its contents.

Response: As noted, USCIS will be suspending the registration requirement for the FY 2020 cap season (beginning April 1, 2019) to complete all requisite user testing of the new H-1B registration system and otherwise ensure the system and process are operable. As the testing continues, USCIS is exploring a number of options for efficient operation and maintenance of the system. As indicated in our responses to the comments pertaining to the Paperwork Reduction Act and the information collections impacted by this rule, while USCIS is seeking OMB approval of the new H-1B Registration Tool information collection as currently proposed, if USCIS determines that collecting additional information is necessary for the effective operation of the registration process, USCIS will comply with the PRA and request OMB approval of any material modifications to that information collection. The H-1B Registration Tool information collection instrument for which DHS is currently seeking OMB approval will be posted to www.reginfo.gov when the final rule publishes and be available for review by the public.

Comment: A few commenters suggested that USCIS require the beneficiary's passport number or Social Security Number and check for duplicates to prevent multiple employers from registering to file an H-1B cap-petition for the same beneficiary. Another individual commenter said there is not enough information required to submit a registration, which could cause the system to be flooded by frivolous registrations. A form letter campaign suggested that the registration should require at least the job title, work site address, and salary offered and employers must attest that the position as described has been offered to the beneficiary being registered. An individual commenter said registration should require at least the job title and SOC code from the LCA, employer address, work site address, LCA Wage Level, and whether the employer is H-1B dependent. Similarly, another commenter suggested that employers should be required to submit a basic application similar to the I-129 application form and certify under penalty of perjury that it has a bona fide job offer to the employee.

A few unions stated that DHS should require employers to disclose any recent or ongoing labor violations or disputes, including EEOC complaints, wage or safety violations, unfair labor practices, or collective bargaining negotiations. A business association suggested that DHS require information related to country of residence and specific educational qualifications (e.g., bachelor's, Master's, Ph.D., date conferred, name and location of institution).

Response: DHS agrees that sufficient information should be required to enable USCIS to identify the beneficiary of the registration, check for duplicate registrations submitted by the same prospective petitioner, and to match selected registrations with subsequently filed H-1B petitions, without overly burdening the employer or collecting unnecessary information. This final rule requires that each registration include, in addition to other basic information, the beneficiary's full name, date of birth, country of birth, country of citizenship, gender, and passport number. USCIS intends to check the system for duplicate registrations during the registration phase similarly to how USCIS currently checks for duplicate H-1B petition filings. At this time DHS does not believe that requesting additional information about the beneficiary or the petitioner is necessary to effectively administer the registration system. Some of the additional information proposed by commenters is information that USCIS would require and review to determine eligibility in the adjudication of the H-1B petition. Establishing eligibility is not a requirement for submitting a registration. USCIS believes the current required information is sufficient to identify the registrant and limit potential fraud and abuse of the registration system. If USCIS determines that collecting additional information is necessary for the effective operation of the registration process, USCIS will comply with the PRA and request OMB approval of any material modifications to that information collection. DHS is not amending the regulations to prohibit multiple employers from filing an H-1B cap-petition for the same beneficiary. DHS regulations, however, already preclude the filing of multiple H-1B cap-subject petitions by related entities for the same beneficiary, unless the related petitioners can establish a legitimate business need for filing multiple cap-petitions for the same beneficiary, and that regulation remains unchanged by this final rule. This final rule authorizes USCIS to collect sufficient information for each registration to mitigate the risk that the registration system will be flooded with frivolous registrations. For example, each registration will require completion of an attestation, and individuals or entities who falsely attest to the bona fides of the registration and submitted frivolous registrations may be referred to appropriate federal law enforcement agencies for investigation and further action as appropriate.

Comment: Some commenters provided input on addressing errors. A company, multiple business associations, and an advocacy group suggested that non-material errors might occur and should not affect a beneficiary's chances of being selected in the lottery, and that USCIS should allow petitioners to correct these errors for [registrations] that are selected when filing the H-1B petition. A law firm suggested that the only material errors that should result in the rejection of filing are errors in the employer's name and beneficiary's name. The commenter explained that information such as birth date could be accidently misfiled because of listing conventions in different countries and need not disqualify someone's ability to file. A professional services company said USCIS should make publicly available reasonable remedies to resolve errors made in good faith by petitioning employers.

Similarly, some commenters provided input on editing registrations. A couple of companies said business needs might change, and that employers should be able to edit registrations for errors or changes in business needs prior to the close of the registration period. A law firm requested that USCIS issue clarifications on how to edit registrations, and suggested that withdrawing and re-submitting a registration should not be counted as multiple filings. The firm also suggested that USCIS establish a warning system for when multiple filings are mistakenly submitted, and that the system allow petitioners to identify cap-subject or master's-cap eligible petitions from the outset. However, another attorney questioned whether employers would be stuck with cap designations if such a feature is included, and cautioned that the registration process would force employers and H-1B candidates to make early decisions that may change later on.

Response: USCIS is exploring a number of options for efficient operation, use, and maintenance of the system. USCIS is considering ways to allow petitioners to correct typographical errors, and may allow petitioners to contact USCIS where they believe such an error was made on a registration. USCIS will allow petitioners to edit a registration up until the petitioner submits the registration. A petitioner may delete a registration and resubmit it prior to the close of the registration period. USCIS will provide guidance on how to use the registration system and edit registrations prior to opening the registration system for the initial registration period.

Comment: A professional association and a law firm said the registration process should include an eligibility assessment for positions and candidates, so that employers who are not well-versed in immigration and H-1B requirements do not take up H-1B cap space. Similarly, an individual commenter stated that the information captured in the current system would not be enough to reduce the burden on USCIS by rejecting non-meritorious petitions.

Response: As noted elsewhere in this rule, submission of the registration is merely an antecedent procedural requirement to properly file the petition. It is not intended to replace the petition adjudication process or assess the eligibility of the beneficiary for the offered position. The purpose of the information provided at the time of registration is to allow USCIS to efficiently identify the prospective H-1B petitioner and the named beneficiary, eliminate duplicate registrations, to select sufficient registrations toward the H-1B cap and the advanced degree exemption, and to match selected registrations with subsequently filed H-1B petitions. As such, DHS is declining to adopt the suggestion of including an eligibility assessment as part of the registration process. DHS also declines to adopt the suggestions to collect additional information regarding the petitioner, beneficiary or proffered position that would go beyond these needs. The selection process is intended to impose little burden, as it is a random process that does not assess eligibility. DHS recognizes that submission of non-meritorious petitions, whether under the new registration process or under the current process, creates an additional administrative burden. This rule, however, is not designed to relieve the burden of adjudicating non-meritorious petitions. The registration process under this final rule is designed to relieve the burden of having to receive several hundred thousand H-1B cap petitions in order to administer the cap selection process.

In addition, USCIS may reopen the registration process if necessary to ensure sufficient number of registrations are selected toward the number projected as needed to reach the numerical allocations (as may be the window for filing petitions). Thus, “cap space” will not go unutilized because of the submission of non-meritorious registrations or petitions.

Comment: A law firm suggested that the regulation should be amended to allow lawyers to file registrations, as they are in the best position to advise employers about the qualifications for H-1B status. The commenter also suggested that USCIS should develop adequate protections to ensure that only authorized company representatives are able to file petitions, warning that without such protections, someone could use an employer's easily-discoverable employer identification number to file hundreds of inappropriate submissions or self-register for H-1B slots.

Response: As discussed elsewhere in this preamble, the regulation will allow attorneys to submit registrations on behalf of petitioning clients, upon completion of a Form G-28, Notice of Entry of Appearance as Attorney or Accredited Representative, for each petitioning client. USCIS is exploring a number of options for efficient operation, use, and maintenance of the system, as well as additional fraud and abuse prevention measures.

Comment: A law firm requested that USCIS ask for beneficiaries' Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS) number during registration to ensure that information is updated in SEVIS if an individual is selected in the lottery.

Response: The registration system is only a preliminary step towards filing of an H-1B cap petition. As noted previously in this preamble, USCIS is only collecting information that is necessary to identify the beneficiary and petitioner for the purpose of effectively conducting the cap allocation selection process and confirming that H-1B cap-subject petitions are based on a selected registration when registration is required. Because a SEVIS number is not necessary for the cap selection process, USCIS declines to collect it at this time.

5. Timeline for the Implementation of the H-1B Registration Requirement

Comment: A number of commenters requested that DHS delay the implementation of the registration process past the FY 2020 cap season, until FY 2021. Most noted that adjusting to a new system so close to the H-1B cap filing season would be difficult and noted the timeframes necessary to prepare petitions and the time, effort, and resources already spent in preparing for the FY 2020 cap season. One commenter also noted that cost-savings would not be achieved for the FY 2020 cap season since petitioners have already begun preparing H-1B cap petitions for the upcoming filing season. Commenters also requested that DHS announce as soon as possible whether it intends to implement or suspend the registration process for the FY 2020 cap season to remove uncertainty for the regulated public and give petitions an adequate opportunity to prepare H-1B petitions.

Response: Based on comments received and ongoing review of the registration system, USCIS will be suspending the registration requirement until such time that the system has been fully tested and modified to address concerns raised by commenters. DHS will publish a notice in the Federal Register before the registration requirement is implemented. USCIS will also conduct outreach and training on the new registration system to the regulated public which will be offered in advance of the cap season during which the registration process will be implemented for the first time.

Comment: A business association stated that there is inadequate time for USCIS to comply with the requirements of the Administrative Procedure Act and/or evaluate all comments received on the proposed rule in time to make changes that would take effect before the start of the 2020 H-1B cap season. Additionally, several commenters asserted that adopting a new registration process for FY 2020 cap-subject H-1B petitions would insert unnecessary uncertainty, as there simply is not enough time to finalize the registration requirement and system for the FY 2020 H-1B cap, and, if DHS wanted such a system implemented for the FY 2020 cap, it should have published the proposed rule much sooner than it did. A commenter also noted that there is insufficient time for USCIS to substitute a two-step registration system for the current one-step procedure.