AGENCY:

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS.

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

This final rule updates the prospective payment rates for inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs) for federal fiscal year (FY) 2020. As required by the statute, this final rule includes the classification and weighting factors for the IRF prospective payment system's (PPS) case-mix groups (CMGs) and a description of the methodologies and data used in computing the prospective payment rates for FY 2020. This final rule rebases and revises the IRF market basket to reflect a 2016 base year rather than the current 2012 base year. Additionally, this final rule revises the CMGs and updates the CMG relative weights and average length of stay (LOS) values beginning with FY 2020, based on analysis of 2 years of data (FYs 2017 and 2018). Although we proposed to use a weighted motor score to assign patients to CMGs, we are finalizing based on public comments the use of an unweighted motor score to assign patients to CMGs beginning with FY 2020. Additionally, we are finalizing the removal of one item from the motor score. We are updating the IRF wage index to use the concurrent fiscal year inpatient prospective payment system (IPPS) wage index beginning with FY 2020. We are amending the regulations to clarify that the determination as to whether a physician qualifies as a rehabilitation physician (that is, a licensed physician with specialized training and experience in inpatient rehabilitation) is made by the IRF. For the IRF Quality Reporting Program (QRP), we are adopting two new measures, modifying an existing measure, and adopting new standardized patient assessment data elements. We are also making updates to reflect our migration to a new data submission system.

DATES:

Effective date: These regulations are effective on October 1, 2019.

Applicability dates: The updated IRF prospective payment rates are applicable for IRF discharges occurring on or after October 1, 2019, and on or before September 30, 2020 (FY 2020). The new and updated quality measures and reporting requirements under the IRF QRP are applicable for IRF discharges occurring on or after October 1, 2020.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Gwendolyn Johnson, (410) 786-6954, for general information.

Catie Kraemer, (410) 786-0179, for information about the IRF payment policies and payment rates.

Kadie Derby, (410) 786-0468, for information about the IRF coverage policies.

Kate Brooks, (410) 786-7877, for information about the IRF quality reporting program.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Inspection of Public Comments: All comments received before the close of the comment period are available for viewing by the public, including any personally identifiable or confidential business information that is included in a comment. We post all comments received before the close of the comment period as soon as possible after they have been received at http://www.regulations.gov. Follow the search instructions on that website to view public comments.

The IRF PPS Addenda along with other supporting documents and tables referenced in this final rule are available through the internet on the CMS website at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/InpatientRehabFacPPS/.

Executive Summary

A. Purpose

This final rule updates the prospective payment rates for IRFs for FY 2020 (that is, for discharges occurring on or after October 1, 2019, and on or before September 30, 2020) as required under section 1886(j)(3)(C) of the Social Security Act (the Act). As required by section 1886(j)(5) of the Act, this final rule includes the classification and weighting factors for the IRF PPS's case-mix groups (CMGs) and a description of the methodologies and data used in computing the prospective payment rates for FY 2020. This final rule also rebases and revises the IRF market basket to reflect a 2016 base year, rather than the current 2012 base year. Additionally, this final rule revises the CMGs and updates the CMG relative weights and average LOS values beginning with FY 2020, based on analysis of 2 years of data (FYs 2017 and 2018). Although we proposed to use a weighted motor score to assign patients to CMGs, we are finalizing based on public comments the use of an unweighted motor score to assign patients to CMGs beginning with FY 2020. Additionally, we are finalizing the removal of one item from the motor score. We are also updating the IRF wage index to use the concurrent FY IPPS wage index for the IRF PPS beginning with FY 2020. We are also amending the regulations at 42 CFR 412.622 to clarify that the determination as to whether a physician qualifies as a rehabilitation physician (that is, a licensed physician with specialized training and experience in inpatient rehabilitation) is made by the IRF. For the IRF QRP, we are adopting two new measures, modifying an existing measure, and adopting new standardized patient assessment data elements. We also include updates related to the system used for the submission of data and related regulation text. We are not finalizing our proposal requiring that IRFs submit data on measures and standardized patient assessment data for which the source of the data is the IRF-PAI to all patients, regardless of payer, but plan to propose this policy in future rulemaking.

B. Summary of Major Provisions

In this final rule, we use the methods described in the FY 2019 IRF PPS final rule (83 FR 38514) to update the prospective payment rates for FY 2020 using updated FY 2018 IRF claims and the most recent available IRF cost report data, which is FY 2017 IRF cost report data. This final rule also rebases and revises the IRF market basket to reflect a 2016 base year rather than the current 2012 base year. Additionally, this final rule revises the CMGs and updates the CMG relative weights and average LOS values beginning with FY 2020, based on analysis of 2 years of data (FYs 2017 and 2018). Although we proposed to use a weighted motor score to assign patients to CMGs, we are finalizing based on public comments the use of an unweighted motor score to assign patients to CMGs beginning with FY 2020. Additionally, we are finalizing the removal of one item from the motor score. We are also updating the IRF wage index to use the concurrent FY IPPS wage index for the IRF PPS beginning in FY 2020. We are also amending the regulations at § 412.622 to clarify that the determination as to whether a physician qualifies as a rehabilitation physician (that is, a licensed physician with specialized training and experience in inpatient rehabilitation) is made by the IRF. We also update requirements for the IRF QRP.

C. Summary of Impacts

I. Background

A. Historical Overview of the IRF PPS

Section 1886(j) of the Act provides for the implementation of a per-discharge PPS for inpatient rehabilitation hospitals and inpatient rehabilitation units of a hospital (collectively, hereinafter referred to as IRFs). Payments under the IRF PPS encompass inpatient operating and capital costs of furnishing covered rehabilitation services (that is, routine, ancillary, and capital costs), but not direct graduate medical education costs, costs of approved nursing and allied health education activities, bad debts, and other services or items outside the scope of the IRF PPS. Although a complete discussion of the IRF PPS provisions appears in the original FY 2002 IRF PPS final rule (66 FR 41316) and the FY 2006 IRF PPS final rule (70 FR 47880), we are providing a general description of the IRF PPS for FYs 2002 through 2019.

Under the IRF PPS from FY 2002 through FY 2005, the prospective payment rates were computed across 100 distinct CMGs, as described in the FY 2002 IRF PPS final rule (66 FR 41316). We constructed 95 CMGs using rehabilitation impairment categories (RICs), functional status (both motor and cognitive), and age (in some cases, cognitive status and age may not be a factor in defining a CMG). In addition, we constructed five special CMGs to account for very short stays and for patients who expire in the IRF.

For each of the CMGs, we developed relative weighting factors to account for a patient's clinical characteristics and expected resource needs. Thus, the weighting factors accounted for the relative difference in resource use across all CMGs. Within each CMG, we created tiers based on the estimated effects that certain comorbidities would have on resource use.

We established the federal PPS rates using a standardized payment conversion factor (formerly referred to as the budget-neutral conversion factor). For a detailed discussion of the budget-neutral conversion factor, please refer to our FY 2004 IRF PPS final rule (68 FR 45684 through 45685). In the FY 2006 IRF PPS final rule (70 FR 47880), we discussed in detail the methodology for determining the standard payment conversion factor.

We applied the relative weighting factors to the standard payment conversion factor to compute the unadjusted prospective payment rates under the IRF PPS from FYs 2002 through 2005. Within the structure of the payment system, we then made adjustments to account for interrupted stays, transfers, short stays, and deaths. Finally, we applied the applicable adjustments to account for geographic variations in wages (wage index), the percentage of low-income patients, location in a rural area (if applicable), and outlier payments (if applicable) to the IRFs' unadjusted prospective payment rates.

For cost reporting periods that began on or after January 1, 2002, and before October 1, 2002, we determined the final prospective payment amounts using the transition methodology prescribed in section 1886(j)(1) of the Act. Under this provision, IRFs transitioning into the PPS were paid a blend of the federal IRF PPS rate and the payment that the IRFs would have received had the IRF PPS not been implemented. This provision also allowed IRFs to elect to bypass this blended payment and immediately be paid 100 percent of the federal IRF PPS rate. The transition methodology expired as of cost reporting periods beginning on or after October 1, 2002 (FY 2003), and payments for all IRFs now consist of 100 percent of the federal IRF PPS rate.

Section 1886(j) of the Act confers broad statutory authority upon the Secretary to propose refinements to the IRF PPS. In the FY 2006 IRF PPS final rule (70 FR 47880) and in correcting amendments to the FY 2006 IRF PPS final rule (70 FR 57166), we finalized a number of refinements to the IRF PPS case-mix classification system (the CMGs and the corresponding relative weights) and the case-level and facility-level adjustments. These refinements included the adoption of the Office of Management and Budget's (OMB) Core-Based Statistical Area (CBSA) market definitions; modifications to the CMGs, tier comorbidities; and CMG relative weights, implementation of a new teaching status adjustment for IRFs; rebasing and revising the market basket index used to update IRF payments, and updates to the rural, low-income percentage (LIP), and high-cost outlier adjustments. Beginning with the FY 2006 IRF PPS final rule (70 FR 47908 through 47917), the market basket index used to update IRF payments was a market basket reflecting the operating and capital cost structures for freestanding IRFs, freestanding inpatient psychiatric facilities (IPFs), and long-term care hospitals (LTCHs) (hereinafter referred to as the rehabilitation, psychiatric, and long-term care (RPL) market basket). Any reference to the FY 2006 IRF PPS final rule in this final rule also includes the provisions effective in the correcting amendments. For a detailed discussion of the final key policy changes for FY 2006, please refer to the FY 2006 IRF PPS final rule.

In the FY 2007 IRF PPS final rule (71 FR 48354), we further refined the IRF PPS case-mix classification system (the CMG relative weights) and the case-level adjustments, to ensure that IRF PPS payments would continue to reflect as accurately as possible the costs of care. For a detailed discussion of the FY 2007 policy revisions, please refer to the FY 2007 IRF PPS final rule.

In the FY 2008 IRF PPS final rule (72 FR 44284), we updated the prospective payment rates and the outlier threshold, revised the IRF wage index policy, and clarified how we determine high-cost outlier payments for transfer cases. For more information on the policy changes implemented for FY 2008, please refer to the FY 2008 IRF PPS final rule.

After publication of the FY 2008 IRF PPS final rule (72 FR 44284), section 115 of the Medicare, Medicaid, and SCHIP Extension Act of 2007 (Pub. L. 110-173, enacted December 29, 2007) (MMSEA) amended section 1886(j)(3)(C) of the Act to apply a zero percent increase factor for FYs 2008 and 2009, effective for IRF discharges occurring on or after April 1, 2008. Section 1886(j)(3)(C) of the Act required the Secretary to develop an increase factor to update the IRF prospective payment rates for each FY. Based on the legislative change to the increase factor, we revised the FY 2008 prospective payment rates for IRF discharges occurring on or after April 1, 2008. Thus, the final FY 2008 IRF prospective payment rates that were published in the FY 2008 IRF PPS final rule (72 FR 44284) were effective for discharges occurring on or after October 1, 2007, and on or before March 31, 2008, and the revised FY 2008 IRF prospective payment rates were effective for discharges occurring on or after April 1, 2008, and on or before September 30, 2008. The revised FY 2008 prospective payment rates are available on the CMS website at http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/InpatientRehabFacPPS/Data-Files.html.

In the FY 2009 IRF PPS final rule (73 FR 46370), we updated the CMG relative weights, the average LOS values, and the outlier threshold; clarified IRF wage index policies regarding the treatment of “New England deemed” counties and multi-campus hospitals; and revised the regulation text in response to section 115 of the MMSEA to set the IRF compliance percentage at 60 percent (the “60 percent rule”) and continue the practice of including comorbidities in the calculation of compliance percentages. We also applied a zero percent market basket increase factor for FY 2009 in accordance with section 115 of the MMSEA. For more information on the policy changes implemented for FY 2009, please refer to the FY 2009 IRF PPS final rule.

In the FY 2010 IRF PPS final rule (74 FR 39762) and in correcting amendments to the FY 2010 IRF PPS final rule (74 FR 50712), we updated the prospective payment rates, the CMG relative weights, the average LOS values, the rural, LIP, teaching status adjustment factors, and the outlier threshold; implemented new IRF coverage requirements for determining whether an IRF claim is reasonable and necessary; and revised the regulation text to require IRFs to submit patient assessments on Medicare Advantage (MA) (formerly called Medicare Part C) patients for use in the 60 percent rule calculations. Any reference to the FY 2010 IRF PPS final rule in this final rule also includes the provisions effective in the correcting amendments. For more information on the policy changes implemented for FY 2010, please refer to the FY 2010 IRF PPS final rule.

After publication of the FY 2010 IRF PPS final rule (74 FR 39762), section 3401(d) of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Pub. L. 111-148, enacted March 23, 2010), as amended by section 10319 of the same Act and by section 1105 of the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 (Pub. L. 111-152, enacted March 30, 2010) (collectively, hereinafter referred to as “PPACA”), amended section 1886(j)(3)(C) of the Act and added section 1886(j)(3)(D) of the Act. Section 1886(j)(3)(C) of the Act requires the Secretary to estimate a multifactor productivity (MFP) adjustment to the market basket increase factor, and to apply other adjustments as defined by the Act. The productivity adjustment applies to FYs from 2012 forward. The other adjustments apply to FYs 2010 to 2019.

Sections 1886(j)(3)(C)(ii)(II) and 1886(j)(3)(D)(i) of the Act defined the adjustments that were to be applied to the market basket increase factors in FYs 2010 and 2011. Under these provisions, the Secretary was required to reduce the market basket increase factor in FY 2010 by a 0.25 percentage point adjustment. Notwithstanding this provision, in accordance with section 3401(p) of the PPACA, the adjusted FY 2010 rate was only to be applied to discharges occurring on or after April 1, 2010. Based on the self-implementing legislative changes to section 1886(j)(3) of the Act, we adjusted the FY 2010 prospective payment rates as required, and applied these rates to IRF discharges occurring on or after April 1, 2010, and on or before September 30, 2010. Thus, the final FY 2010 IRF prospective payment rates that were published in the FY 2010 IRF PPS final rule (74 FR 39762) were used for discharges occurring on or after October 1, 2009, and on or before March 31, 2010, and the adjusted FY 2010 IRF prospective payment rates applied to discharges occurring on or after April 1, 2010, and on or before September 30, 2010. The adjusted FY 2010 prospective payment rates are available on the CMS website at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/InpatientRehabFacPPS/IRF-Rules-and-Related-Files.html.

In addition, sections 1886(j)(3)(C) and (D) of the Act also affected the FY 2010 IRF outlier threshold amount because they required an adjustment to the FY 2010 RPL market basket increase factor, which changed the standard payment conversion factor for FY 2010. Specifically, the original FY 2010 IRF outlier threshold amount was determined based on the original estimated FY 2010 RPL market basket increase factor of 2.5 percent and the standard payment conversion factor of $13,661. However, as adjusted, the IRF prospective payments were based on the adjusted RPL market basket increase factor of 2.25 percent and the revised standard payment conversion factor of $13,627. To maintain estimated outlier payments for FY 2010 equal to the established standard of 3 percent of total estimated IRF PPS payments for FY 2010, we revised the IRF outlier threshold amount for FY 2010 for discharges occurring on or after April 1, 2010, and on or before September 30, 2010. The revised IRF outlier threshold amount for FY 2010 was $10,721.

Sections 1886(j)(3)(C)(ii)(II) and 1886(j)(3)(D)(i) of the Act also required the Secretary to reduce the market basket increase factor in FY 2011 by a 0.25 percentage point adjustment. The FY 2011 IRF PPS notice (75 FR 42836) and the correcting amendments to the FY 2011 IRF PPS notice (75 FR 70013) described the required adjustments to the FY 2010 and FY 2011 IRF PPS prospective payment rates and outlier threshold amount for IRF discharges occurring on or after April 1, 2010, and on or before September 30, 2011. It also updated the FY 2011 prospective payment rates, the CMG relative weights, and the average LOS values. Any reference to the FY 2011 IRF PPS notice in this final rule also includes the provisions effective in the correcting amendments. For more information on the FY 2010 and FY 2011 adjustments or the updates for FY 2011, please refer to the FY 2011 IRF PPS notice.

In the FY 2012 IRF PPS final rule (76 FR 47836), we updated the IRF prospective payment rates, rebased and revised the RPL market basket, and established a new QRP for IRFs in accordance with section 1886(j)(7) of the Act. We also consolidated, clarified, and revised existing policies regarding IRF hospitals and IRF units of hospitals to eliminate unnecessary confusion and enhance consistency. For more information on the policy changes implemented for FY 2012, please refer to the FY 2012 IRF PPS final rule.

The FY 2013 IRF PPS notice (77 FR 44618) described the required adjustments to the FY 2013 prospective payment rates and outlier threshold amount for IRF discharges occurring on or after October 1, 2012, and on or before September 30, 2013. It also updated the FY 2013 prospective payment rates, the CMG relative weights, and the average LOS values. For more information on the updates for FY 2013, please refer to the FY 2013 IRF PPS notice.

In the FY 2014 IRF PPS final rule (78 FR 47860), we updated the prospective payment rates, the CMG relative weights, and the outlier threshold amount. We also updated the facility-level adjustment factors using an enhanced estimation methodology, revised the list of diagnosis codes that count toward an IRF's 60 percent rule compliance calculation to determine “presumptive compliance,” revised sections of the IRF patient assessment instrument (IRF-PAI), revised requirements for acute care hospitals that have IRF units, clarified the IRF regulation text regarding limitation of review, updated references to previously changed sections in the regulations text, and updated requirements for the IRF QRP. For more information on the policy changes implemented for FY 2014, please refer to the FY 2014 IRF PPS final rule.

In the FY 2015 IRF PPS final rule (79 FR 45872) and the correcting amendments to the FY 2015 IRF PPS final rule (79 FR 59121), we updated the prospective payment rates, the CMG relative weights, and the outlier threshold amount. We also revised the list of diagnosis codes that count toward an IRF's 60 percent rule compliance calculation to determine “presumptive compliance,” revised sections of the IRF-PAI, and updated requirements for the IRF QRP. Any reference to the FY 2015 IRF PPS final rule in this final rule also includes the provisions effective in the correcting amendments. For more information on the policy changes implemented for FY 2015, please refer to the FY 2015 IRF PPS final rule.

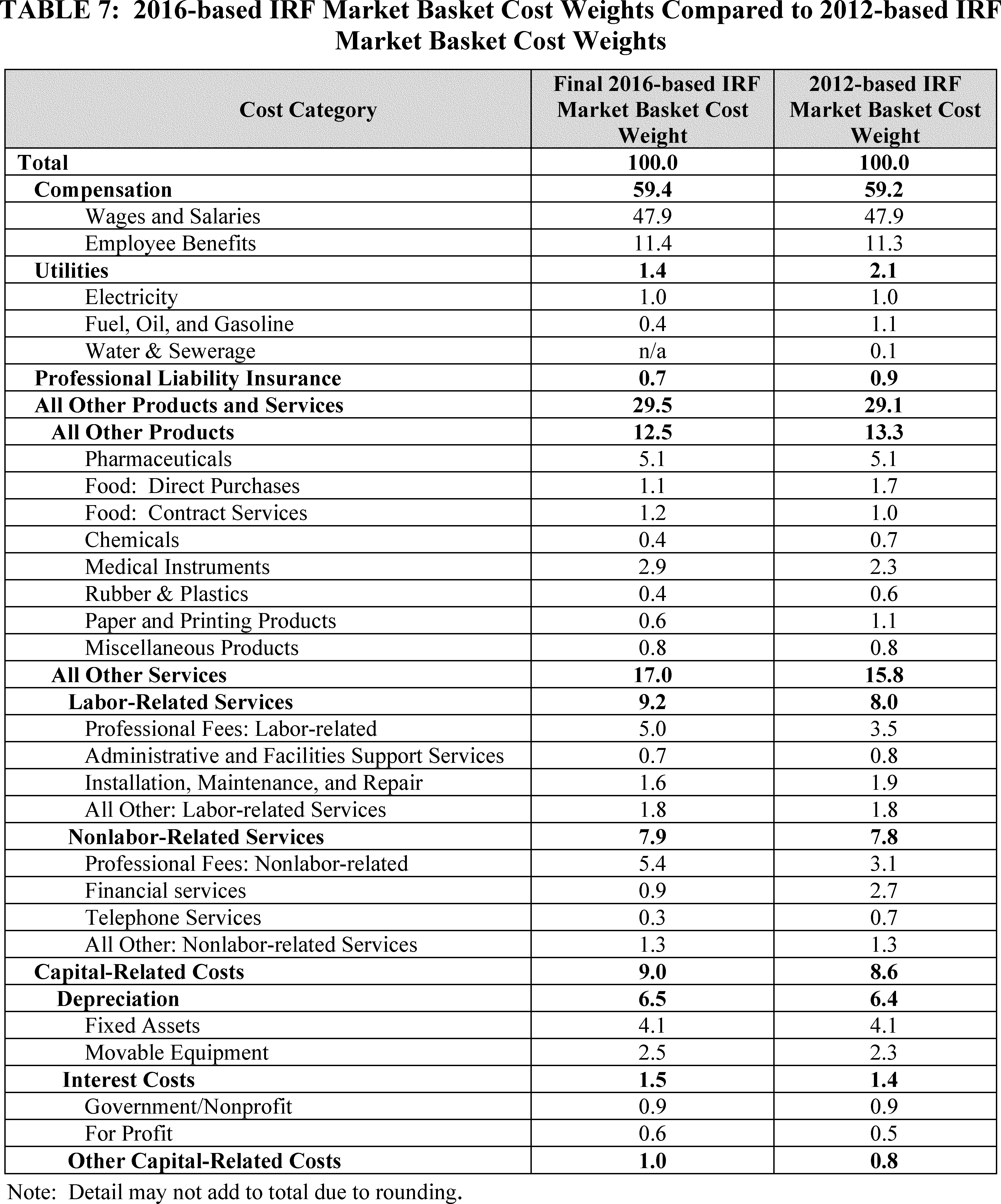

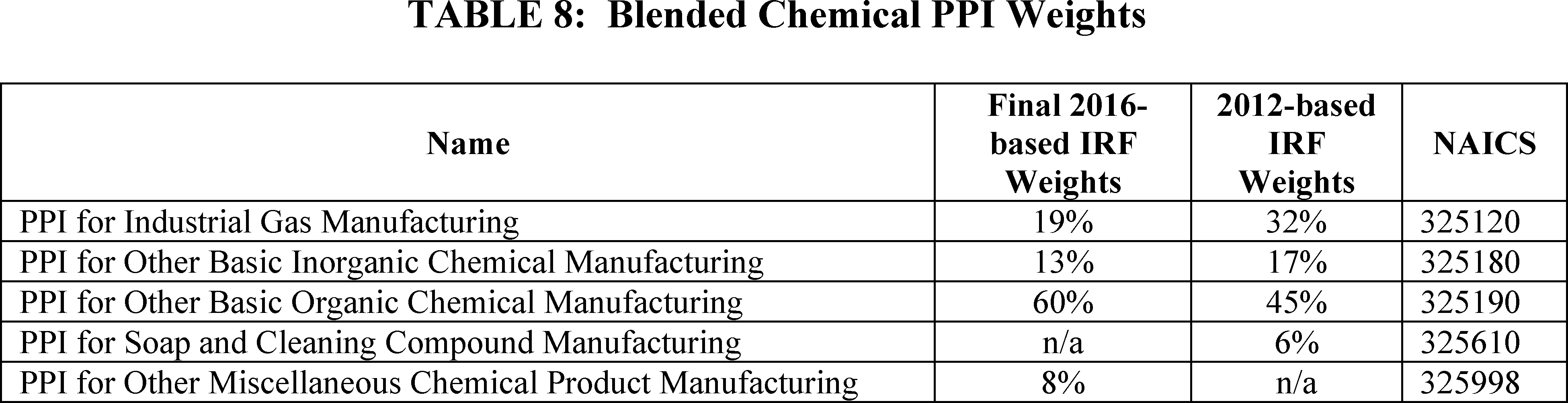

In the FY 2016 IRF PPS final rule (80 FR 47036), we updated the prospective payment rates, the CMG relative weights, and the outlier threshold amount. We also adopted an IRF-specific market basket that reflects the cost structures of only IRF providers, a blended 1-year transition wage index based on the adoption of new OMB area delineations, a 3-year phase-out of the rural adjustment for certain IRFs due to the new OMB area delineations, and updates for the IRF QRP. For more information on the policy changes implemented for FY 2016, please refer to the FY 2016 IRF PPS final rule.

In the FY 2017 IRF PPS final rule (81 FR 52056) and the correcting amendments to the FY 2017 IRF PPS final rule (81 FR 59901), we updated the prospective payment rates, the CMG relative weights, and the outlier threshold amount. We also updated requirements for the IRF QRP. Any reference to the FY 2017 IRF PPS final rule in this final rule also includes the provisions effective in the correcting amendments. For more information on the policy changes implemented for FY 2017, please refer to the FY 2017 IRF PPS final rule.

In the FY 2018 IRF PPS final rule (82 FR 36238), we updated the prospective payment rates, the CMG relative weights, and the outlier threshold amount. We also revised the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) diagnosis codes that are used to determine presumptive compliance under the “60 percent rule,” removed the 25 percent payment penalty for IRF-PAI late transmissions, removed the voluntary swallowing status item (Item 27) from the IRF-PAI, summarized comments regarding the criteria used to classify facilities for payment under the IRF PPS, provided for a subregulatory process for certain annual updates to the presumptive methodology diagnosis code lists, adopted the use of height/weight items on the IRF-PAI to determine patient body mass index (BMI) greater than 50 for cases of single-joint replacement under the presumptive methodology, and updated requirements for the IRF QRP. For more information on the policy changes implemented for FY 2018, please refer to the FY 2018 IRF PPS final rule.

In the FY 2019 IRF PPS final rule (83 FR 38514), we updated the prospective payment rates, the CMG relative weights, and the outlier threshold amount. We also alleviated administrative burden for IRFs by removing the FIMTM instrument and associated Function Modifiers from the IRF-PAI beginning in FY 2020 and revised certain IRF coverage requirements to reduce the amount of required paperwork in the IRF setting beginning in FY 2019. Additionally, we incorporated certain data items located in the Quality Indicators section of the IRF-PAI into the IRF case-mix classification system using analysis of 2 years of data (FYs 2017 and 2018) beginning in FY 2020. For the IRF QRP, we adopted a new measure removal factor, removed two measures from the IRF QRP measure set, and codified a number of program requirements in our regulations. For more information on the policy changes implemented for FY 2019, please refer to the FY 2019 IRF PPS final rule.

B. Provisions of the PPACA Affecting the IRF PPS in FY 2012 and Beyond

The PPACA included several provisions that affect the IRF PPS in FYs 2012 and beyond. In addition to what was previously discussed, section 3401(d) of the PPACA also added section 1886(j)(3)(C)(ii)(I) of the Act (providing for a “productivity adjustment” for FY 2012 and each subsequent fiscal year). The productivity adjustment for FY 2020 is discussed in section VI.D. of this final rule. Section 1886(j)(3)(C)(ii)(II) of the Act provides that the application of the productivity adjustment to the market basket update may result in an update that is less than 0.0 for a fiscal year and in payment rates for a fiscal year being less than such payment rates for the preceding fiscal year.

Sections 3004(b) of the PPACA and section 411(b) of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (Pub. L. 114-10, enacted April 16, 2015) (MACRA) also addressed the IRF PPS. Section 3004(b) of PPACA reassigned the previously designated section 1886(j)(7) of the Act to section 1886(j)(8) of the Act and inserted a new section 1886(j)(7) of the Act, which contains requirements for the Secretary to establish a QRP for IRFs. Under that program, data must be submitted in a form and manner and at a time specified by the Secretary. Beginning in FY 2014, section 1886(j)(7)(A)(i) of the Act requires the application of a 2 percentage point reduction to the market basket increase factor otherwise applicable to an IRF (after application of paragraphs (C)(iii) and (D) of section 1886(j)(3) of the Act) for a fiscal year if the IRF does not comply with the requirements of the IRF QRP for that fiscal year. Application of the 2 percentage point reduction may result in an update that is less than 0.0 for a fiscal year and in payment rates for a fiscal year being less than such payment rates for the preceding fiscal year. Reporting-based reductions to the market basket increase factor are not cumulative; they only apply for the FY involved. Section 411(b) of MACRA amended section 1886(j)(3)(C) of the Act by adding paragraph (iii), which required us to apply for FY 2018, after the application of section 1886(j)(3)(C)(ii) of the Act, an increase factor of 1.0 percent to update the IRF prospective payment rates.

C. Operational Overview of the Current IRF PPS

As described in the FY 2002 IRF PPS final rule (66 FR 41316), upon the admission and discharge of a Medicare Part A Fee-for-Service (FFS) patient, the IRF is required to complete the appropriate sections of a PAI, designated as the IRF-PAI. In addition, beginning with IRF discharges occurring on or after October 1, 2009, the IRF is also required to complete the appropriate sections of the IRF-PAI upon the admission and discharge of each Medicare Advantage (MA) patient, as described in the FY 2010 IRF PPS final rule (74 FR 39762 and 74 FR 50712). All required data must be electronically encoded into the IRF-PAI software product. Generally, the software product includes patient classification programming called the Grouper software. The Grouper software uses specific IRF-PAI data elements to classify (or group) patients into distinct CMGs and account for the existence of any relevant comorbidities.

The Grouper software produces a five-character CMG number. The first character is an alphabetic character that indicates the comorbidity tier. The last four characters are numeric characters that represent the distinct CMG number. Free downloads of the Inpatient Rehabilitation Validation and Entry (IRVEN) software product, including the Grouper software, are available on the CMS website at http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/InpatientRehabFacPPS/Software.html.

Once a Medicare Part A FFS patient is discharged, the IRF submits a Medicare claim as a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (Pub. L. 104-191, enacted August 21, 1996) (HIPAA) compliant electronic claim or, if the Administrative Simplification Compliance Act of 2002 (Pub. L. 107-105, enacted December 27, 2002) (ASCA) permits, a paper claim (a UB-04 or a CMS-1450 as appropriate) using the five-character CMG number and sends it to the appropriate Medicare Administrative Contractor (MAC). In addition, once a MA patient is discharged, in accordance with the Medicare Claims Processing Manual, chapter 3, section 20.3 (Pub. 100-04), hospitals (including IRFs) must submit an informational-only bill (Type of Bill (TOB) 111), which includes Condition Code 04 to their MAC. This will ensure that the MA days are included in the hospital's Supplemental Security Income (SSI) ratio (used in calculating the IRF LIP adjustment) for fiscal year 2007 and beyond. Claims submitted to Medicare must comply with both ASCA and HIPAA.

Section 3 of the ASCA amended section 1862(a) of the Act by adding paragraph (22), which requires the Medicare program, subject to section 1862(h) of the Act, to deny payment under Part A or Part B for any expenses for items or services for which a claim is submitted other than in an electronic form specified by the Secretary. Section 1862(h) of the Act, in turn, provides that the Secretary shall waive such denial in situations in which there is no method available for the submission of claims in an electronic form or the entity submitting the claim is a small provider. In addition, the Secretary also has the authority to waive such denial in such unusual cases as the Secretary finds appropriate. For more information, see the “Medicare Program; Electronic Submission of Medicare Claims” final rule (70 FR 71008). Our instructions for the limited number of Medicare claims submitted on paper are available at http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c25.pdf.

Section 3 of the ASCA operates in the context of the administrative simplification provisions of HIPAA, which include, among others, the requirements for transaction standards and code sets codified in 45 CFR part 160 and part 162, subparts A and I through R (generally known as the Transactions Rule). The Transactions Rule requires covered entities, including covered health care providers, to conduct covered electronic transactions according to the applicable transaction standards. (See the CMS program claim memoranda at http://www.cms.gov/ElectronicBillingEDITrans/ and listed in the addenda to the Medicare Intermediary Manual, Part 3, section 3600).

The MAC processes the claim through its software system. This software system includes pricing programming called the “Pricer” software. The Pricer software uses the CMG number, along with other specific claim data elements and provider-specific data, to adjust the IRF's prospective payment for interrupted stays, transfers, short stays, and deaths, and then applies the applicable adjustments to account for the IRF's wage index, percentage of low-income patients, rural location, and outlier payments. For discharges occurring on or after October 1, 2005, the IRF PPS payment also reflects the teaching status adjustment that became effective as of FY 2006, as discussed in the FY 2006 IRF PPS final rule (70 FR 47880).

D. Advancing Health Information Exchange

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has a number of initiatives designed to encourage and support the adoption of interoperable health information technology and to promote nationwide health information exchange to improve health care. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) and CMS work collaboratively to advance interoperability across settings of care, including post-acute care.

To further interoperability in post-acute care, we developed a Data Element Library (DEL) to serve as a publicly-available centralized, authoritative resource for standardized data elements and their associated mappings to health IT standards. The DEL furthers CMS' goal of data standardization and interoperability. These interoperable data elements can reduce provider burden by allowing the use and exchange of healthcare data, support provider exchange of electronic health information for care coordination, person-centered care, and support real-time, data driven, clinical decision making. Standards in the Data Element Library (https://del.cms.gov/) can be referenced on the CMS website and in the ONC Interoperability Standards Advisory (ISA). The 2019 ISA is available at https://www.healthit.gov/isa.

The 21st Century Cures Act (Pub. L. 114-255, enacted December 13, 2016) (Cures Act), requires HHS to take new steps to enable the electronic sharing of health information ensuring interoperability for providers and settings across the care continuum. In another important provision, Congress defined “information blocking” as practices likely to interfere with, prevent, or materially discourage access, exchange, or use of electronic health information, and established new authority for HHS to discourage these practices. In March 2019, ONC and CMS published the proposed rules, “21st Century Cures Act: Interoperability, Information Blocking, and the ONC Health IT Certification Program,” (84 FR 7424) and “Interoperability and Patient Access” (84 FR 7610) to promote secure and more immediate access to health information for patients and healthcare providers through the implementation of information blocking provisions of the Cures Act and the use of standardized application programming interfaces (APIs) that enable easier access to electronic health information. We solicited comment on the two proposed rules. We invited providers to learn more about these important developments and how they are likely to affect IRFs.

II. Summary of Provisions of the Proposed Rule

In the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule, we proposed to update the IRF prospective payment rates for FY 2020 and to rebase and revise the IRF market basket to reflect a 2016 base year rather than the current 2012 base year. We also proposed to replace the previously finalized unweighted motor score with a weighted motor score to assign patients to CMGs and remove one item from the score beginning with FY 2020 and to revise the CMGs and update the CMG relative weights and average LOS values beginning with FY 2020, based on analysis of 2 years of data (FYs 2017 and 2018). We also proposed to use the concurrent FY IPPS wage index for the IRF PPS beginning with FY 2020. We also solicited comments on stakeholder concerns regarding the appropriateness of the wage index used to adjust IRF payments. We proposed to amend the regulations at § 412.622 to clarify that the determination as to whether a physician qualifies as a rehabilitation physician (that is, a licensed physician with specialized training and experience in inpatient rehabilitation) is made by the IRF.

The proposed policy changes and updates to the IRF prospective payment rates for FY 2020 are as follows:

- Describe a proposed weighted motor score to replace the previously finalized unweighted motor score to assign a patient to a CMG, the removal of one item from the score, and revisions to the CMGs beginning on October 1, 2019, based on analysis of 2 years of data (FYs 2017 and 2018) using the Quality Indicator items in the IRF-PAI. This includes proposed revisions to the CMG relative weights and average LOS values for FY 2020, in a budget neutral manner, as discussed in section III. of the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule (84 FR 17244, 17249 through 17260).

- Describe the proposed rebased and revised IRF market basket to reflect a 2016 base year rather than the current 2012 base year as discussed in section V. of the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule (84 FR 17244, 17261 through 17273).

- Update the IRF PPS payment rates for FY 2020 by the proposed market basket increase factor, based upon the most current data available, with a proposed productivity adjustment required by section 1886(j)(3)(C)(ii)(I) of the Act, as described in section V. of the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule (84 FR 17244, 17274 through 17275).

- Describe the proposed update to the IRF wage index to use the concurrent FY IPPS wage index and the FY 2020 proposed labor-related share in a budget-neutral manner, as described in section V. of the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule (84 FR 17244, 17276 through 17279).

- Describe the continued use of FY 2014 facility-level adjustment factors, as discussed in section IV. of the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule (84 FR 17244, 17260 through 17261).

- Describe the calculation of the IRF standard payment conversion factor for FY 2020, as discussed in section V. of the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule (84 FR 17244, 17280 through 17282).

- Update the outlier threshold amount for FY 2020, as discussed in section VI. of the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule (84 FR 17244, 17283 through 17284).

- Update the cost-to-charge ratio (CCR) ceiling and urban/rural average CCRs for FY 2020, as discussed in section VI. of the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule (84 FR 17244 at 17284).

- Describe the proposed amendments to the regulations at § 412.622 to clarify that the determination as to whether a physician qualifies as a rehabilitation physician (that is, a licensed physician with specialized training and experience in inpatient rehabilitation) is made by the IRF, as discussed in section VII. of the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule (84 FR 17244, 17284 through 17285).

- Updates to the requirements for the IRF QRP, as discussed in section VIII. of the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule (84 FR 17244, 17285 through 17330).

III. Analysis and Response to Public Comments

We received 1,257 timely responses from the public, many of which contained multiple comments on the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule (84 FR 17244). The majority consisted of form letters, in which we received multiple copies of two types of identically-worded letters that had been signed and submitted by different individuals. We received comments from various trade associations, IRFs, individual physicians, therapists, clinicians, health care industry organizations, and health care consulting firms. The following sections, arranged by subject area, include a summary of the public comments that we received, and our responses.

IV. Refinements to the Case-Mix Classification System Beginning With FY 2020

A. Background

Section 1886(j)(2)(A) of the Act requires the Secretary to establish CMGs for payment under the IRF PPS and a method of classifying specific IRF patients within these groups. Under section 1886(j)(2)(B) of the Act, the Secretary must assign each CMG an appropriate weighting factor that reflects the relative facility resources used for patients classified within the group as compared to patients classified within other groups. Additionally, section 1886(j)(2)(C)(i) of the Act requires the Secretary from time to time to adjust the established classifications and weighting factors as appropriate to reflect changes in treatment patterns, technology, case-mix, number of payment units for which payment is made under title XVIII of the Act, and other factors which may affect the relative use of resources. Such adjustments must be made in a manner so that changes in aggregate payments under the classification system are a result of real changes and are not a result of changes in coding that are unrelated to real changes in case mix.

In the FY 2019 IRF PPS final rule (83 FR 38533 through 38549), we finalized the removal of the Functional Independence Measure (FIMTM) instrument and associated Function Modifiers from the IRF-PAI and the incorporation of an unweighted additive motor score derived from 19 data items located in the Quality Indicators section of the IRF-PAI beginning with FY 2020 (83 FR 38535 through 38536, 38549). As discussed in section IV.B of this final rule, based on further analysis to examine the potential impact of weighting the motor score, we proposed to replace the previously finalized unweighted motor score with a weighted motor score and remove one item from the score beginning with FY 2020.

Additionally, as noted in the FY 2019 IRF PPS final rule (83 FR 38534), the incorporation of the data items from the Quality Indicator section of the IRF-PAI into the IRF case-mix classification system necessitates revisions to the CMGs to ensure that IRF payments are calculated accurately. We finalized the use of data items from the Quality Indicators section of the IRF-PAI to construct the functional status scores used to classify IRF patients in the IRF case-mix classification system for purposes of establishing payment under the IRF PPS beginning with FY 2020, but modified our proposal based on public comments to incorporate 2 years of data (FYs 2017 and 2018) into our analyses used to revise the CMG definitions (83 FR 38549). We stated that any changes to the proposed CMG definitions resulting from the incorporation of an additional year of data (FY 2018) into the analysis would be addressed in future rulemaking prior to their implementation beginning in FY 2020. As discussed in section III.C of the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule (84 FR 17244, 17250 through 17260), we proposed to revise the CMGs based on analysis of 2 years of data (FYs 2017 and 2018) beginning with FY 2020. We also proposed to update the relative weights and average LOS values associated with the revised CMGs beginning with FY 2020.

B. Proposed Use of a Weighted Motor Score Beginning With FY 2020

As noted in the FY 2019 IRF PPS final rule (83 FR 38535), the IRF case-mix classification system currently uses a weighted motor score based on FIMTM data items to assign patients to CMGs under the IRF PPS through FY 2019. More information on the development and implementation of this motor score can be found in the FY 2006 IRF PPS final rule (70 FR 47896 through 47900). In the FY 2019 IRF PPS final rule (83 FR 38535 through 38536, 38549), we finalized the incorporation of an unweighted additive motor score derived from 19 data items located in the Quality Indicators section of the IRF-PAI beginning with FY 2020. We did not propose a weighted motor score at the time, because we believed that the unweighted motor score would facilitate greater understanding among the provider community, as it is less complex. However, we also noted that we would take comments in favor of a weighted motor score into consideration in future analysis. In response to feedback we received from various stakeholders and professional organizations regarding the use of an unweighted motor score and requesting that we consider weighting the motor score, we extended our contract with Research Triangle Institute, International (RTI) to examine the potential impact of weighting the motor score. Based on this analysis, discussed further below, we believed that a weighted motor score would improve the accuracy of payments to IRFs and proposed to replace the previously finalized unweighted motor score with a weighted motor score to assign patients to CMGs beginning with FY 2020.

The previously finalized motor score is calculated by summing the scores of the 19 data items, with equal weight applied to each item. The 19 data items are (83 FR 38535):

- GG0130A1 Eating.

- GG0130B1 Oral hygiene.

- GG0130C1 Toileting hygiene.

- GG0130E1 Shower/bathe self.

- GG0130F1 Upper-body dressing.

- GG0130G1 Lower-body dressing.

- GG0130H1 Putting on/taking off footwear.

- GG0170A1 Roll left and right.

- GG0170B1 Sit to lying.

- GG0170C1 Lying to sitting on side of bed.

- GG0170D1 Sit to stand.

- GG0170E1 Chair/bed-to-chair transfer.

- GG0170F1 Toilet transfer.

- GG0170I1 Walk 10 feet.

- GG0170J1 Walk 50 feet with two turns.

- GG0170K1 Walk 150 feet.

- GG0170M1 One step curb.

- H0350 Bladder continence.

- H0400 Bowel continence.

In response to feedback we received from various stakeholders and professional organizations requesting that we consider applying weights to the motor score, we extended our contract with RTI to explore the potential of applying unique weights to each of the 19 items in the motor score.

As part of their analysis, RTI examined the degree to which the items used to construct the motor score were related to one another and adjusted their weighting methodology to account for their findings. RTI considered a number of different weighting methodologies to develop a weighted index that would increase the predictive power of the IRF case-mix classification system while at the same time maintaining simplicity. RTI used regression analysis to explore the relationship of the motor score items to costs. This analysis was undertaken to determine the impact of each of the items on cost and then to weight each item in the index according to its relative impact on cost. Based on findings from this analysis, we proposed to remove the item GG0170A1 Roll left and right from the motor score as this item was found to have a high degree of multicollinearity with other items in the motor score and would have resulted in either a negative or non-significant coefficient. As such, we did not believe it would be appropriate to include this item in the motor score calculation. Using the revised motor score composed of the remaining 18 items identified above, RTI designed a weighting methodology for the motor score that could be applied uniformly across all RICs. For a more detailed discussion of the analysis used to construct the weighted motor score, we refer readers to the March 2019 technical report entitled “Analyses to Inform the Use of Standardized Patient Assessment Data Elements in the Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Prospective Payment System”, available at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/InpatientRehabFacPPS/Research.html. Findings from this analysis suggested that the use of a weighted motor score index slightly improves the ability of the IRF PPS to predict patient costs. Based on this analysis, we proposed to use a weighted motor score for the purpose of determining IRF payments.

Table 1 shows the proposed weights for each component of the motor score, averaged to 1, obtained through the regression analysis.

We proposed to determine the motor score by applying each of the weights indicated in Table 1 to the score of each corresponding item, as finalized in the FY 2019 IRF PPS final rule (83 FR 38535 through 38537), and then summing the weighted scores for each of the 18 items that compose the motor score.

We received several comments on the proposal to replace the previously finalized unweighted motor score with a weighted motor score to assign patients to CMGs under the IRF PPS and our proposal to remove the item GG0170A1 Roll left and right from the calculation of the motor score beginning with FY 2020, that is, for all discharges beginning on or after October 1, 2019. As summarized in more detail below, with the exception of one comment from MedPAC, the commenters overwhelmingly requested that CMS delay implementation of a weighted motor score and use an unweighted motor score to assign patients to CMGs until we can more fully analyze and work with stakeholders on developing a weighted motor score methodology.

In response to public comments, we carefully considered whether to finalize the proposed weighted motor score or go back to using an unweighted motor score to assign patients to CMGs. Although the proposed weighted motor score results in a slight improvement in the ability of the IRF PPS to predict patient costs and thus the accuracy of IRF PPS payments (less than 0.18 difference in accuracy between the weighted and the unweighted motor scores), we acknowledge the unweighted motor score is conceptually simpler and, as such, believe it will ease providers' transition to the use of the data items located in the Quality Indicators section of the IRF-PAI (also referred to as section GG items). Thus, we are finalizing based on public comments the use of an unweighted motor score to assign patients to CMGs beginning with FY 2020. We appreciate the commenters' suggestions on the weighting methodology and will take them into consideration as we explore possible refinements to the case-mix classification system in the future.

Comment: Although several commenters noted appreciation for the fact that we analyzed a weighted motor score in response to their comments on the FY 2019 IRF PPS proposed rule (83 FR 38546), these same commenters expressed concerns with the actual weight values that CMS proposed for FY 2020, as indicated in Table 1, and stated that we should go back to an unweighted motor score so that we can do further analysis and collaborate with stakeholders to further refine the weighting methodology. Some commenters expressed concern that CMS might be proposing higher weights for the self-care items than for the mobility items, in contrast to the current weighted motor score, which weights mobility items higher than self-care items. Some commenters specifically requested that CMS explain why the weight for the eating item increased from 0.6 under the current weighting methodology to 2.7 under the proposed methodology, and requested we explain what we believe this change will mean for patients with eating deficits. Commenters were also generally concerned by what they suggested were large differences in the weight value assignments between the current and proposed motor score.

Response: We used simple ordinary least squares regression analysis of the data that IRFs submitted to us in FYs 2017 and 2018 to calculate the proposed weight values for the motor score, in response to stakeholder feedback on the FY 2019 IRF PPS proposed rule (83 FR 38546). Commenters are correct that the proposed weights for the motor score items, in comparison with the current weights, shift some of the weight from the mobility to the self-care items. We also note that the proposed weights assigned to the bowel and bladder function items increased compared with the current weights. These changes are all reflective of the data the IRFs submitted to us in FYs 2017 and 2018.

Regarding the proposed increase in the weight for the eating item, it is important to note key differences in the coding guidelines between the FIMTM eating item and the section GG eating item that may have contributed to the change in the relative importance of this item for predicting IRF costs. For item GG0130A, Eating, assistance with tube feedings is not considered when coding this item. If a patient does not eat or drink by mouth but is instead tube fed, item GG0130A must be coded as 88—“Not attempted due to medical condition or safety concerns” or 09—“Not applicable”. Both of these responses would be recoded to a 01—“Dependent” for the purposes of assigning the patient to a CMG. This differs from the coding instructions for the FIMTM eating item used in the current motor score, which takes into consideration assistance with tube feedings in scoring the item. For example, according to the FIMTM instructions, a patient who could administer the tube feeding completely independently could receive a score of 7-Complete independence on the eating item.

In regards to the suggested differences in the weight value assignments between the current and proposed methodologies, we note that in certain cases the proposed weights were divided among multiple items in the motor score that were found to be highly correlated to avoid overweighting any particular measure of function. For instance, the three items (GG0170I1, GG0170J1, and GG0170K1) that assess walking function were each assigned a proposed weight of 0.8. When summed together, the weight value for walking under the proposed methodology is 2.4, which is slightly higher than the weight value of 1.6 for the single walking item used in the current motor score.

Comment: One commenter disagreed with the removal of item GG0170A1 roll left and right from the motor score and noted it is an important functional task in the IRF setting. Some commenters questioned the use of averaging values across pairs of items that were correlated and inquired why the roll left and right item was removed from the motor score while other correlated items were not removed. Commenters also inquired about the use of the item “walk 10 feet” to derive the weights for the “walk 50 feet” and “walk 150 feet” items.

Response: We appreciate the commenter's concerns regarding the removal of item GG0170A1 from the motor score. As described in detail in the technical report, “Analyses to Inform the Use of Standardized Patient Assessment Data Elements in the Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Prospective Payment System,” the roll left and right item was found to have a high degree of multicollinearity with other standardized patient assessment elements and to be inversely correlated with costs after controlling for each of the other self-care and mobility items. This relationship persisted when this item was paired with the other correlated items. The continued inclusion of this item in the motor score would have resulted in either a negative or non-significant coefficient. As such, we do not believe it is appropriate to include this item in the construction of the motor score. The other item pairs that were found to be correlated did not generate negative or non-significant coefficients, and were therefore maintained in the calculation of the motor score.

Unlike the FIMTM instrument, the items from the quality indicator section of the IRF-PAI sometimes use more than one item to measure functional areas. As discussed in more detail in the technical report, we noted that a few items were found to be highly correlated. Because of the correlation, we proposed to use an average score for some items so as to avoid introducing bias or inappropriately overweighting any particular functional area. We note this methodology is consistent with the methodology used under the Patient Driven Payment Model (PDPM), as described in more detail in the FY 2019 SNF final rule (83 FR 39204) and the accompanying technical report entitled “Skilled Nursing Facilities Patient-Driven Payment Model Technical Report” available on the CMS website at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/SNFPPS/therapyresearch.html.

Regarding the “walk 10 feet” item, that item was used to derive the weights for the “walk 50 feet” and “walk 150 feet” items as these three items were found to be highly correlated and the “walk 150 feet” item had a high proportion of observations coded on admission with “activity not attempted” codes.

Comment: Some commenters requested that CMS apply the current motor score weights associated with the FIMTM items to the revised motor score while other commenters requested that CMS postpone weighting the motor score until additional data can be collected and analyzed. While a few commenters were supportive of using a weighted motor score, other commenters suggested that CMS use a 1-year payment model or phase in the use of a weighted motor score.

Response: We do not believe it would be appropriate to apply the weight values associated with the FIMTM items to the components of the revised motor score, as these weights would not accurately reflect how the various components of the revised motor score contribute to predicting patient costs. We used simple ordinary least squares regression analysis of the data that IRFs submitted to us in FYs 2017 and 2018 to calculate the proposed weight values for the revised motor score. Changes in patient demographics, treatment practices, technology, and other factors that may affect the relative use of resources in an IRF since the motor score weights were originally calculated have likely contributed to changes in the weight values applied across the self-care and mobility items. We proposed to apply weights to the motor score items because RTI's analysis indicated that a weighted motor score would improve the classification of patients into CMGs, which in turn would improve the accuracy of payments to IRFs. However, as discussed above, in response to public comments, we carefully considered whether to finalize the proposed weighted motor score or go back to using an unweighted motor score to assign patients to CMGs. Although the proposed weighted motor score results in a slight improvement in the ability of the IRF PPS to predict patient costs and thus the accuracy of IRF PPS payments (less than 0.18 difference in accuracy between the weighted and the unweighted motor scores), we acknowledge the unweighted motor score is conceptually simpler and, as such, believe it will ease providers' transition to the use of the data items located in the Quality Indicators section of the IRF-PAI (also referred to as section GG items). Thus, we are finalizing based on public comments the use of an unweighted motor score, in which each of the 18 items have a weight of 1, to assign patients to CMGs beginning with FY 2020.

Comment: Commenters expressed concern that the analysis performed by RTI did not explicitly follow the analysis conducted by RAND when the motor score weights were developed for FY 2006 (70 FR 47896 through 47900) and that RTI based their analyses on 2 years of data instead of several years of data. Additionally, commenters requested more information on the other weighting methodologies that RTI considered.

Response: We disagree with the commenters that the RAND analysis for FY 2006 used more years of data than RTI's analysis for the FY 2020 proposed rule. As discussed in the FY 2006 IRF PPS final rule (70 FR 47897), RAND performed regression analysis on less than 2 full years of data (calendar year (CY) 2002 and FY 2003) to derive the current motor score weights. In contrast, RTI used 2 full years of data (FYs 2017 and 2018) to perform the analysis for the weighted motor score proposed in the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule. As the FYs 2017 and 2018 data portrays the most recent and complete picture of patients under the IRF PPS, we believe it was sufficient and appropriate to utilize for the analysis for the proposed rule.

While RTI utilized a different weighting methodology than was used by RAND in 2006, the overall model prediction using the weighted motor score developed by RAND and the weighted motor score developed by RTI is extremely similar. The model using the CMGs based on the standardized patient assessment data elements and comorbidity tiers to predict wage-adjusted costs of care has an r-squared value is 0.3358, while the r-squared value is 0.3169 for the CMGs in the current IRF PPS. This is indicative of similar model performance regardless of model specification. The item weights that the RAND work notes as “optimally weighted” are weights that were constructed separately for each RIC. These were not the weights that were used in the final weights developed by RAND.

RTI also examined weighing methodologies utilizing a general linear model (GLM) and log transformed ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models, as well as the OLS model described in more detail in the technical report. All three models had comparable model fit and generated similar item weights. Based on the greater simplicity achieved through the use of the OLS regression model we believe using the OLS regression was appropriate to maintain simplicity and transparency in the payment system.

Comment: Commenters disagreed with the omission of the wheelchair mobility items from the items used to construct the motor score.

Response: We appreciate the commenters' concerns about wheelchair-dependent patients. As most recently discussed in the FY 2019 IRF PPS final rule (83 FR 38546) in response to similar stakeholder comments, we explained our rationale for not including the wheelchair mobility items in the construction of the finalized motor score. We continue to believe that the higher resource needs of wheelchair dependent patients in IRFs will be better accounted for by not including a wheelchair item in the motor score at this time. Patients that are considered wheelchair dependent or unable to walk will be accounted for through the “not attempted” response codes captured through other items, especially some of the walking items, that are included in the motor score. In this way, we ensure that IRFs will be appropriately compensated for the higher costs they incur in treating wheelchair-dependent patients. We refer readers to the FY 2019 IRF PPS final rule (83 FR 38546) and the technical report entitled “Analyses to Inform the Use of Standardized Patient Assessment Data Elements in the Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Prospective Payment System” for more information on the rationale as to why this item was not included in the calculation of the motor score.

Comment: Commenters expressed concern with the weighted motor score and questioned the reliability and validity of the weighted motor score. Some commenters stated that they believe the weighted and unweighted motor scores have shown little to no correlation with the weighted motor score currently in use, and therefore, questioned if the weighted motor score could accurately measure patient severity.

Response: We disagree with the commenters' suggestion that unweighted and weighted motor scores have shown little to no correlation with the weighted motor score currently in use as our analysis shows a strong correlation between the scores. In addition, each of the proposed Quality Indicators data items that were included in the motor score were found to have statistically significant correlation with IRF costs. As discussed in the technical report “Analyses to Inform the Use of Standardized Patient Assessment Data Elements in the Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Prospective Payment System” the use of a weighted motor score was found to increase the predictive ability of the payment model.

Comment: Commenters requested that CMS make available the data utilized in the analyses including patient assessment data, matching claims data, and additional facility and cost report data to enable stakeholders to replicate the analyses.

Response: We appreciate the commenters' feedback regarding the types of information that would be most useful to them in replicating our analyses. We are unable to make patient assessment and claims data publicly available on the CMS website because these data contain personally identifiable information. However, we believe that we released sufficient information in the proposed rule, the accompanying data files, and the technical report entitled “Analyses to Inform the Use of Standardized Patient Assessment Data Elements in the Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Prospective Payment System,” to enable stakeholders to submit meaningful comments on the underlying analyses and methodologies used to revise the IRF case-mix classification system, to pose alternative approaches, and to assess the impacts of the proposed revisions.

Comment: A few commenters noted that they did not believe that CMS has performed the thorough data analyses and engagement with the provider community that are necessary prior to making significant changes to the existing IRF PPS. These commenters requested that we solicit additional feedback from the stakeholder community, including convening technical advisory panels (TEPs), to provide additional transparency into the underlying analyses and to delay implementation of a weighted motor score until we conduct additional engagements with stakeholders.

Response: We value transparency in our processes and will continue to engage stakeholders in future development of payment policies. We appreciate the offers from stakeholders to assist in the development of future revisions to payment policies and we recognize the value from these partnerships. However, for something as analytically simple as running a regression analysis to determine the weights for the motor score items that best reflect patients' resource needs in the IRF, we do not believe that a TEP is necessary.

As noted above, although the proposed weighted motor score results in a slight improvement in the ability of the IRF PPS to predict patient costs and thus the accuracy of IRF PPS payments (less than 0.18 difference in accuracy between the weighted and the unweighted motor scores), we acknowledge the unweighted motor score is conceptually simpler and, as such, believe it will ease providers' transition to the use of the data items located in the Quality Indicators section of the IRF-PAI (also referred to as section GG items). Thus, we are finalizing based on public comments the use of an unweighted motor score to assign patients to CMGs beginning with FY 2020. We appreciate the stakeholders' comments on this topic and will take them into consideration for future analysis.

Comment: A few commenters requested that CMS provide additional information regarding the provider specific impact analysis file that accompanied the rule, such as a data dictionary describing the data used to calculate the impacts.

Response: In conjunction with the release of the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule, we posted a provider-specific impact analysis file that compared estimated payments to providers for FY 2020 without the proposed revisions to the CMGs with estimated payments to providers for FY 2020 with the proposed revisions to the CMGs. We believe that this file gives IRFs added information to enable them to see how their individual payments would be affected by the proposed changes to the CMGs. We updated this provider specific impact analysis file shortly after it was initially posted to include additional information regarding the underlying data used to calculate the provider specific impacts, and we believe that this additional information is responsive to commenters' requests. The file can be downloaded from the CMS website at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/InpatientRehabFacPPS/IRF-Rules-and-Related-Files.html. We appreciate the commenters' suggestions regarding the additional types of information that would be most useful to them to further facilitate understanding of our analyses.

As previously discussed, we proposed a weighted motor score as it was found to slightly improve the predicative ability of the case-mix system and thus the accuracy of IRF PPS payments. However, nearly all of the comments we received requested that we revert to an unweighted motor score for the various reasons discussed above. While we continue to believe that a weighted motor score is slightly more accurate, the difference is small, and in light of the conceptual simplicity achieved through the use of an unweighted motor score, which we believe will ease providers' transition to the use of the data items located in the Quality Indicators section of the IRF-PAI, we are finalizing the use of an unweighted motor score, in which each of the 18 items used in the score have an equal weight of 1, to assign patients to CMGs beginning with FY 2020. Additionally, we are finalizing the proposed removal of one item (GG0170A1 Roll left to right) from the motor score beginning with FY 2020. Effective for all discharges beginning on or after October 1, 2019, we will use an unweighted motor score as indicated in Table 2 to determine a beneficiary's CMG placement.

C. Revisions to the CMGs and Updates to the CMG Relative Weights and Average Length of Stay Values Beginning With FY 2020

In the FY 2019 IRF PPS final rule (83 FR 38549), we finalized the use of data items from the Quality Indicators section of the IRF-PAI to construct the functional status scores used to classify IRF patients in the IRF case-mix classification system for purposes of establishing payment under the IRF PPS beginning with FY 2020, but modified our proposal based on public comments to incorporate 2 years of data (FYs 2017 and 2018) into our analyses used to revise the CMG definitions. We stated that any changes to the proposed CMG definitions resulting from the incorporation of an additional year of data (FY 2018) into the analysis would be addressed in future rulemaking prior to their implementation beginning in FY 2020. Additionally, we stated that we would also update the relative weights and average LOS values associated with any revised CMG definitions in future rulemaking.

As noted in the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule (84 FR 17251), we continued our contract with RTI to support us in developing proposed revisions to the CMGs used under the IRF PPS based on analysis of 2 years of data (FYs 2017 and 2018). The process RTI uses for its analysis, which is based on a Classification and Regression Tree (CART) algorithm, is described in detail in the FY 2019 IRF PPS final rule (83 FR 38536 through 38540). RTI used this analysis to revise the CMGs utilizing FYs 2017 and 2018 claim and assessment data and to develop revised CMGs that reflect the use of the data items collected in the Quality Indicators section of the IRF-PAI, incorporating the proposed weighted motor score described in the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule. However, as discussed in section IV.B of this final rule, we are finalizing based on public comments the use of an unweighted motor score to assign patients to a CMGs beginning in with FY 2020.

To develop the proposed revised CMGs, RTI used CART analysis to divide patients into payment groups based on similarities in their clinical characteristics and relative costs. As part of this analysis, RTI imposed some typically-used constraints on the payment group divisions (for example, on the minimum number of cases that could be in the resulting payment groups and the minimum dollar payment amount differences between groups) to identify the optimal set of payment groups. For a more detailed discussion of the analysis used to revise the CMGs for FY 2020, we refer readers to the March 2019 technical report entitled, “Analyses to Inform the Use of Standardized Patient Assessment Data Elements in the Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Prospective Payment System” available at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/InpatientRehabFacPPS/Research.html. Additionally, we refer readers to the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule (84 FR 17250 through 17260) for more information on the proposed revisions to the CMGs.

As noted above, we are finalizing the use of an unweighted motor score beginning with FY 2020. As the motor score is a key input in the CART analysis used to revise the CMGs, the use of the unweighted motor score required that the CART analysis be rerun utilizing the unweighted motor score. RTI utilized the same methodology described in the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule (84 FR 17250 through 17260) to support us in developing revisions to the CMGs, incorporating the unweighted motor score, as described in section IV.B of this final rule. The revised CMGs can be found in Table 3.

After developing the revised CMGs, RTI then calculated the relative weights and average LOS values for each revised CMG using the same methodologies that we have used to update the CMG relative weights and average LOS values each fiscal year since 2009 (when we implemented an update to this methodology). More information about the methodology used to update the CMG relative weights can be found in the FY 2009 IRF PPS final rule (73 FR 46372 through 46374). For FY 2020, we proposed to use the FYs 2017 and 2018 IRF claims and FY 2017 IRF cost report data to update the CMG relative weights and average LOS values. In calculating the CMG relative weights, we use a hospital-specific relative value method to estimate operating (routine and ancillary services) and capital costs of IRFs. As noted in the FY 2019 IRF PPS final rule (83 FR 38521), this is the same methodology that we have used to update the CMG relative weights and average LOS values each fiscal year since we implemented an update to the methodology in the FY 2009 IRF PPS final rule (73 FR 46372 through 46374). More information on the methodology used to update calculate the CMG relative weights and average LOS values can found in the March 2019 technical report entitled “Analyses to Inform the Use of Standardized Patient Assessment Data Elements in the Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Prospective Payment System” available at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/InpatientRehabFacPPS/Research.html. Consistent with the methodology that we have used to update the IRF classification system in each instance in the past, we proposed to update the relative weights associated with the revised CMGs for FY 2020 in a budget neutral manner by applying a budget neutrality factor to the standard payment amount. To calculate the appropriate budget neutrality factor for use in updating the FY 2020 CMG relative weights, we used the following steps:

Step 1. Calculate the estimated total amount of IRF PPS payments for FY 2020 (with no changes to the CMG relative weights).

Step 2. Calculate the estimated total amount of IRF PPS payments for FY 2020 by applying the changes to the CMGs and the associated CMG relative weights (as described in this final rule).

Step 3. Divide the amount calculated in step 1 by the amount calculated in step 2 to determine the budget neutrality factor (1.0016) that would maintain the same total estimated aggregate payments in FY 2020 with and without the changes to the CMGs and the associated CMG relative weights.

Step 4. Apply the budget neutrality factor (1.0016) to the FY 2019 IRF PPS standard payment amount after the application of the budget-neutral wage adjustment factor.

We note that, as we typically do, we updated our data between the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed and final rules to ensure that we use the most recent available data in calculating IRF PPS payments. Additionally, we are finalizing the use of unweighted motor score beginning in with FY 2020 which generated revisions to the CMGs and relative weights. Based on our analysis using this updated data and an unweighted motor score, we now estimate a budget neutrality factor of (1.0010) to maintain the same total estimated aggregate payments in FY 2020 with and without the changes to the CMGs and the associated CMG relative weights. For FY 2020 we will apply the budget neutrality factor (1.0010) to the FY 2019 IRF PPS standard payment amount after the application of the budget-neutral wage adjustment factor.

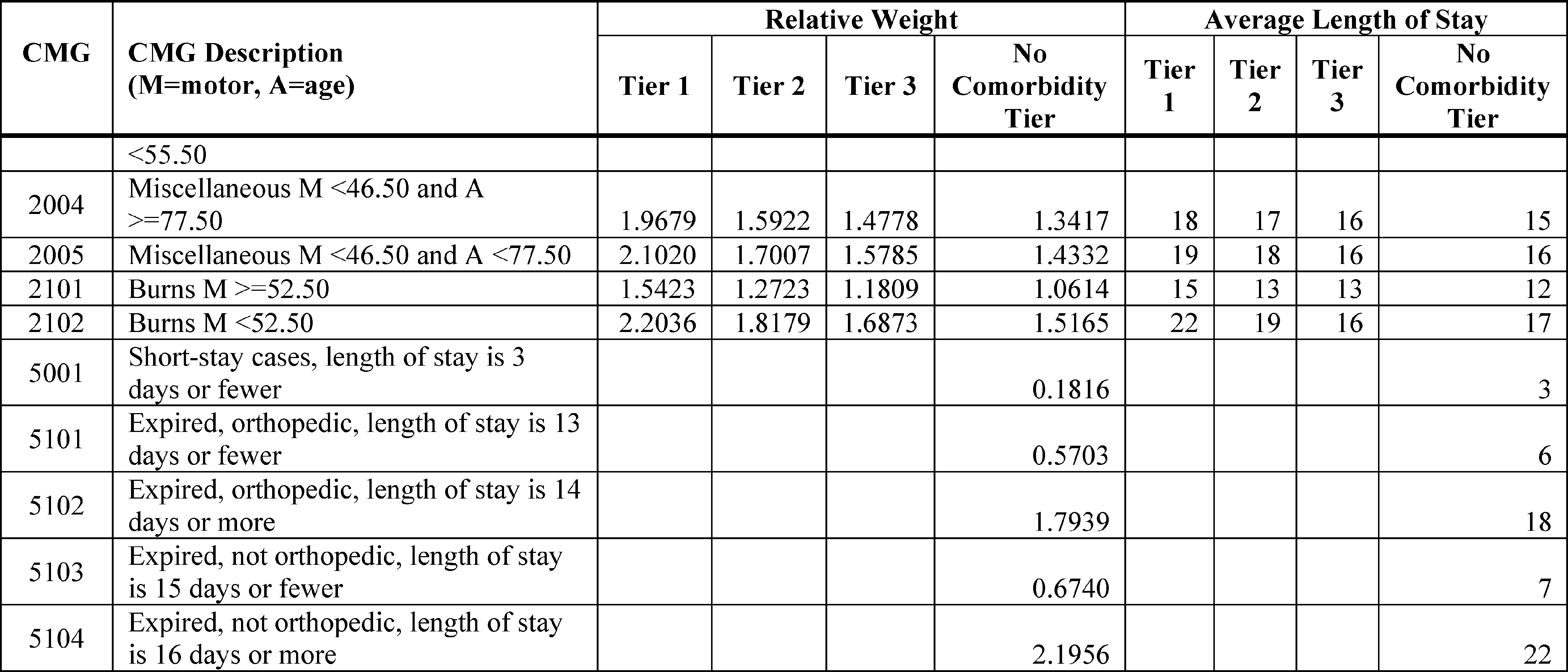

The relative weights and average LOS values for those revised CMGs (found in Table 3) were calculated using the same methodology described in the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule, which is the same methodology that we have used to update the CMG relative weights and average LOS values each fiscal year since we implemented an update to the methodology in FY 2009. The revised CMGs (reflecting the unweighted motor score) and their respective descriptions, as well as the comorbidity tiers, corresponding relative weights and the average LOS values for each CMG and tier for FY 2020 are shown in Table 3. The average LOS for each CMG is used to determine when an IRF discharge meets the definition of a short-stay transfer, which results in a per diem case level adjustment. In section V.H. of this final rule, we discuss the proposed use of the existing methodology to calculate the standard payment conversion factor for FY 2020.

We received a number of comments on the proposed revisions to the CMGs based on analysis of 2 years of data (FYs 2017 and 2018) and the proposed updates to the relative weights and average LOS values associated with the revised CMGs beginning with FY 2020, that is, for all discharges beginning on or after October 1, 2019, which are summarized below.

Comment: A number of commenters were appreciative of the use of 2 years of data to revise the CMGs; however, commenters expressed concern with the proposed CMG revisions and suggested that these changes could result in payment rate compression or a misalignment between payments and the costs of caring for patients. Commenters suggested payment compression would result in reduced payments for higher acuity patients and increased payments for lower acuity patients which could compromise access to care for patients with certain impairments. Additionally, some commenters questioned why there would be fewer CMGs within some RICs and suggested having fewer CMGs would also contribute to payment rate compression.

Response: We disagree with the commenters that revisions to CMGs will lead to payment rate compression or could compromise access to care for any particular group of patients. As the revised CMGs are reflective of the data that IRFs submitted to us in FYs 2017 and 2018, we believe the revised CMGs reflect the distinct resource needs of the current Medicare IRF population. We believe the revised CMGs more accurately predict resource use in IRFs and better align payments with the expected costs of treating patients in the IRF setting. As such, we believe that the revised CMGs may in fact improve access to and quality of care for IRF patients by increasing the accuracy of IRF payments to providers.