AGENCY:

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS.

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

We are revising the Medicare hospital inpatient prospective payment systems (IPPS) for operating and capital-related costs of acute care hospitals to implement changes arising from our continuing experience with these systems for FY 2020 and to implement certain recent legislation. We also are making changes relating to Medicare graduate medical education (GME) for teaching hospitals and payments to critical access hospital (CAHs). In addition, we are providing the market basket update that will apply to the rate-of-increase limits for certain hospitals excluded from the IPPS that are paid on a reasonable cost basis, subject to these limits for FY 2020. We are updating the payment policies and the annual payment rates for the Medicare prospective payment system (PPS) for inpatient hospital services provided by long-term care hospitals (LTCHs) for FY 2020. In this FY 2020 IPPS/LTCH PPS final rule, we are addressing wage index disparities impacting low wage index hospitals; providing for an alternative IPPS new technology add-on payment pathway for certain transformative new devices and qualified infectious disease products; and revising the calculation of the IPPS new technology add-on payment. In addition, we are revising and clarifying our policies related to the substantial clinical improvement criterion used for evaluating applications for the new technology add-on payment under the IPPS.

We are establishing new requirements or revising existing requirements for quality reporting by specific Medicare providers (acute care hospitals, PPS-exempt cancer hospitals, and LTCHs). We also are establishing new requirements and revising existing requirements for eligible hospitals and critical access hospitals (CAHs) participating in the Medicare and Medicaid Promoting Interoperability Programs. We are updating policies for the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Program, the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, and the Hospital-Acquired Condition (HAC) Reduction Program.

DATES:

This final rule is effective October 1, 2019.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Donald Thompson, (410) 786-4487, and Michele Hudson, (410) 786-4487, Operating Prospective Payment, MS-DRGs, Wage Index, New Medical Service and Technology Add-On Payments, Hospital Geographic Reclassifications, Graduate Medical Education, Capital Prospective Payment, Excluded Hospitals, Medicare Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) Payment Adjustment, Medicare-Dependent Small Rural Hospital (MDH) Program, Low-Volume Hospital Payment Adjustment, and Critical Access Hospital (CAH) Issues.

Michele Hudson, (410) 786-4487, Mark Luxton, (410) 786-4530, and Emily Lipkin, (410) 786-3633, Long-Term Care Hospital Prospective Payment System and MS-LTC-DRG Relative Weights Issues.

Siddhartha Mazumdar, (410) 786-6673, Rural Community Hospital Demonstration Program Issues.

Jeris Smith, (410) 786-0110, Frontier Community Health Integration Project Demonstration Issues.

Erin Patton, (410) 786-2437, Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program Administration Issues.

Lein Han, 410-786-0205, Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program—Measures Issues.

Michael Brea, (410) 786-4961, Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program Issues.

Annese Abdullah-Mclaughlin, (410) 786-2995, Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program—Measures Issues.

Grace Snyder, (410) 786-0700 and James Poyer, (410) 786-2261, Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting and Hospital Value-Based Purchasing—Program Administration, Validation, and Reconsideration Issues.

Cindy Tourison, (410) 786-1093, Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting and Hospital Value-Based Purchasing—Measures Issues Except Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems Issues.

Elizabeth Goldstein, (410) 786-6665, Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting and Hospital Value-Based Purchasing—Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems Measures Issues.

Nekeshia McInnis, (410) 786-4486 and Ronique Evans, (410) 786-1000, PPS-Exempt Cancer Hospital Quality Reporting Issues.

Mary Pratt, (410) 786-6867, Long-Term Care Hospital Quality Data Reporting Issues.

Elizabeth Holland, (410) 786-1309, Dylan Podson (410) 786-5031, and Bryan Rossi (410) 786-065l, Promoting Interoperability Programs.

Benjamin Moll, (410) 786-4390, Provider Reimbursement Review Board Appeals Issues.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Tables Available Through the Internet on the CMS Website

In the past, a majority of the tables referred to throughout this preamble and in the Addendum to the proposed rule and the final rule were published in the Federal Register, as part of the annual proposed and final rules. However, beginning in FY 2012, the majority of the IPPS tables and LTCH PPS tables are no longer published in the Federal Register. Instead, these tables, generally, will be available only through the internet. The IPPS tables for this FY 2020 final rule are available through the internet on the CMS website at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/index.html. Click on the link on the left side of the screen titled, “FY 2020 IPPS Final Rule Home Page” or “Acute Inpatient—Files for Download.” The LTCH PPS tables for this FY 2020 final rule are available through the internet on the CMS website at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/LongTermCareHospitalPPS/index.html under the list item for Regulation Number CMS-1716-F. For further details on the contents of the tables referenced in this final rule, we refer readers to section VI. of the Addendum to this FY 2020 IPPS/LTCH PPS final rule.

Readers who experience any problems accessing any of the tables that are posted on the CMS websites, as previously identified, should contact Michael Treitel at (410) 786-4552.

Table of Contents

I. Executive Summary and Background

A. Executive Summary

B. Background Summary

C. Summary of Provisions of Recent Legislation Implemented in This Final Rule

D. Issuance of Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

E. Advancing Health Information Exchange

II. Changes to Medicare Severity Diagnosis-Related Group (MS-DRG) Classifications and Relative Weights

A. Background

B. MS-DRG Reclassifications

C. Adoption of the MS-DRGs in FY 2008

D. FY 2020 MS-DRG Documentation and Coding Adjustment

E. Refinement of the MS-DRG Relative Weight Calculation

F. Changes to Specific MS-DRG Classifications

G. Recalibration of the FY 2020 MS-DRG Relative Weights

H. Add-On Payments for New Services and Technologies for FY 2020

III. Changes to the Hospital Wage Index for Acute Care Hospitals

A. Background

B. Worksheet S-3 Wage Data for the FY 2020 Wage Index

C. Verification of Worksheet S-3 Wage Data

D. Method for Computing the FY 2020 Unadjusted Wage Index

E. Occupational Mix Adjustment to the FY 2020 Wage Index

F. Analysis and Implementation of the Occupational Mix Adjustment and the Final FY 2020 Occupational Mix Adjusted Wage Index

G. Application of the Rural Floor, Expired Imputed Floor Policy, and Application of the State Frontier Floor

H. FY 2020 Wage Index Tables

I. Revisions to the Wage Index Based on Hospital Redesignations and Reclassifications

J. Out-Migration Adjustment Based on Commuting Patterns of Hospital Employees

K. Reclassification From Urban to Rural Under Section 1886(d)(8)(E) of the Act Implemented at 42 CFR 412.103

L. Process for Requests for Wage Index Data Corrections

M. Labor-Related Share for the FY 2020 Wage Index

N. Final Policies To Address Wage Index Disparities Between High and Low Wage Index Hospitals

IV. Other Decisions and Changes to the IPPS for Operating Costs

A. Changes to MS-DRGs Subject to Postacute Care Transfer and MS-DRG Special Payment Policies

B. Changes in the Inpatient Hospital Updates for FY 2020 (§ 412.64(d))

C. Rural Referral Centers (RRCs) Annual Updates to Case-Mix Index and Discharge Criteria (§ 412.96)

D. Payment Adjustment for Low-Volume Hospitals (§ 412.101)

E. Indirect Medical Education (IME) Payment Adjustment (§ 412.105)

F. Payment Adjustment for Medicare Disproportionate Share Hospitals (DSHs) for FY 2020 (§ 412.106)

G. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program: Updates and Changes (§§ 412.150 Through 412.154)

H. Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Program: Policy Changes

I. Hospital-Acquired Condition (HAC) Reduction Program

J. Payments for Indirect and Direct Graduate Medical Education Costs (§§ 412.105 and 413.75 Through 413.83)

K. Rural Community Hospital Demonstration Program

V. Changes to the IPPS for Capital-Related Costs

A. Overview

B. Additional Provisions

C. Annual Update for FY 2020

VI. Changes for Hospitals Excluded From the IPPS

A. Rate-of-Increase in Payments to Excluded Hospitals for FY 2020

B. Methodologies and Requirements for TEFRA Adjustments to Rate-of-Increase Ceiling

C. Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs)

VII. Changes to the Long-Term Care Hospital Prospective Payment System (LTCH PPS) for FY 2020

A. Background of the LTCH PPS

B. Medicare Severity Long-Term Care Diagnosis-Related Group (MS-LTC-DRG) Classifications and Relative Weights for FY 2020

C. Payment Adjustment for LTCH Discharges That Do Not Meet the Applicable Discharge Payment Percentage

D. Changes to the LTCH PPS Payment Rates and Other Changes to the LTCH PPS for FY 2020

VIII. Quality Data Reporting Requirements for Specific Providers and Suppliers

A. Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program

B. PPS-Exempt Cancer Hospital Quality Reporting (PCHQR) Program

C. Long-Term Care Hospital Quality Reporting Program (LTCH QRP)

D. Changes to the Medicare and Medicaid Promoting Interoperability Programs

IX. MedPAC Recommendations

X. Other Required Information

A. Publicly Available Data

B. Collection of Information Requirements

XI. Provider Reimbursement Review Board (PRRB) Appeals

Regulation Text

Addendum—Schedule of Standardized Amounts, Update Factors, and Rate-of-Increase Percentages Effective With Cost Reporting Periods Beginning on or After October 1, 2019 and Payment Rates for LTCHs Effective With Discharges Occurring on or After October 1, 2019

I. Summary and Background

II. Changes to the Prospective Payment Rates for Hospital Inpatient Operating Costs for Acute Care Hospitals for FY 2020

A. Calculation of the Adjusted Standardized Amount

B. Adjustments for Area Wage Levels and Cost-of-Living

C. Calculation of the Prospective Payment Rates

III. Changes to Payment Rates for Acute Care Hospital Inpatient Capital-Related Costs for FY 2020

A. Determination of Federal Hospital Inpatient Capital-Related Prospective Payment Rate Update

B. Calculation of the Inpatient Capital-Related Prospective Payments for FY 2020

C. Capital Input Price Index

IV. Changes to Payment Rates for Excluded Hospitals: Rate-of-Increase Percentages for FY 2020

V. Updates to the Payment Rates for the LTCH PPS for FY 2020

A. LTCH PPS Standard Federal Payment Rate for FY 2020

B. Adjustment for Area Wage Levels Under the LTCH PPS for FY 2020

C. LTCH PPS Cost-of-Living Adjustment (COLA) for LTCHs Located in Alaska and Hawaii

D. Adjustment for LTCH PPS High-Cost Outlier (HCO) Cases

E. Update to the IPPS Comparable/Equivalent Amounts To Reflect the Statutory Changes to the IPPS DSH Payment Adjustment Methodology

F. Computing the Adjusted LTCH PPS Federal Prospective Payments for FY 2020

VI. Tables Referenced in This FY 2020 IPPS/LTCH PPS Final Rule and Available Through the Internet on the CMS Website

Appendix A—Economic Analyses

I. Regulatory Impact Analysis

A. Statement of Need

B. Overall Impact

C. Objectives of the IPPS and the LTCH PPS

D. Limitations of Our Analysis

E. Hospitals Included in and Excluded From the IPPS

F. Effects on Hospitals and Hospital Units Excluded From the IPPS

G. Quantitative Effects of the Policy Changes Under the IPPS for Operating Costs

H. Effects of Other Policy Changes

I. Effects of Changes in the Capital IPPS

J. Effects of Payment Rate Changes and Policy Changes Under the LTCH PPS

K. Effects of Requirements for Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program

L. Effects of Requirements for the PPS-Exempt Cancer Hospital Quality Reporting (PCHQR) Program

M. Effects of Requirements for the Long-Term Care Hospital Quality Reporting Program (LTCH QRP)

N. Effects of Requirements Regarding the Medicare Promoting Interoperability Program

O. Alternatives Considered

P. Reducing Regulation and Controlling Regulatory Costs

Q. Overall Conclusion

R. Regulatory Review Costs

II. Accounting Statements and Tables

A. Acute Care Hospitals

B. LTCHs

III. Regulatory Flexibility Act (RFA) Analysis

IV. Impact on Small Rural Hospitals

V. Unfunded Mandate Reform Act (UMRA) Analysis

VI. Executive Order 13175

VII. Executive Order 12866

Appendix B: Recommendation of Update Factors for Operating Cost Rates of Payment for Inpatient Hospital Services

I. Background

II. Inpatient Hospital Update for FY 2020

A. FY 2020 Inpatient Hospital Update

B. Update for SCHs and MDHs for FY 2020

C. FY 2020 Puerto Rico Hospital Update

D. Update for Hospitals Excluded From the IPPS

E. Update for LTCHs for FY 2020

III. Secretary's Recommendation

IV. MedPAC Recommendation for Assessing Payment Adequacy and Updating Payments in Traditional Medicare

I. Executive Summary and Background

A. Executive Summary

1. Purpose and Legal Authority

This FY 2020 IPPS/LTCH PPS final rule makes payment and policy changes under the Medicare inpatient prospective payment systems (IPPS) for operating and capital-related costs of acute care hospitals as well as for certain hospitals and hospital units excluded from the IPPS. In addition, it makes payment and policy changes for inpatient hospital services provided by long-term care hospitals (LTCHs) under the long-term care hospital prospective payment system (LTCH PPS). This final rule also makes policy changes to programs associated with Medicare IPPS hospitals, IPPS-excluded hospitals, and LTCHs. In this final rule, we are addressing wage index disparities impacting low wage index hospitals; providing for an alternative IPPS new technology add-on payment pathway for certain transformative new devices and qualified infectious disease products; revising the calculation of the IPPS new technology add-on payment; and making revisions and clarifications related to the substantial clinical improvement criterion under the IPPS.

We are establishing new requirements and revising existing requirements for quality reporting by specific providers (acute care hospitals, PPS-exempt cancer hospitals, and LTCHs) that are participating in Medicare. We also are establishing new requirements and revising existing requirements for eligible hospitals and CAHs participating in the Medicare and Medicaid Promoting Interoperability Programs. We are updating policies for the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Program, the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, and the Hospital-Acquired Condition (HAC) Reduction Program.

Under various statutory authorities, we are making changes to the Medicare IPPS, to the LTCH PPS, and to other related payment methodologies and programs for FY 2020 and subsequent fiscal years. These statutory authorities include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Section 1886(d) of the Social Security Act (the Act), which sets forth a system of payment for the operating costs of acute care hospital inpatient stays under Medicare Part A (Hospital Insurance) based on prospectively set rates. Section 1886(g) of the Act requires that, instead of paying for capital-related costs of inpatient hospital services on a reasonable cost basis, the Secretary use a prospective payment system (PPS).

- Section 1886(d)(1)(B) of the Act, which specifies that certain hospitals and hospital units are excluded from the IPPS. These hospitals and units are: Rehabilitation hospitals and units; LTCHs; psychiatric hospitals and units; children's hospitals; cancer hospitals; extended neoplastic disease care hospitals, and hospitals located outside the 50 States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico (that is, hospitals located in the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa). Religious nonmedical health care institutions (RNHCIs) are also excluded from the IPPS.

- Sections 123(a) and (c) of the BBRA (Pub. L. 106-113) and section 307(b)(1) of the BIPA (Pub. L. 106-554) (as codified under section 1886(m)(1) of the Act), which provide for the development and implementation of a prospective payment system for payment for inpatient hospital services of LTCHs described in section 1886(d)(1)(B)(iv) of the Act.

- Sections 1814(l), 1820, and 1834(g) of the Act, which specify that payments are made to critical access hospitals (CAHs) (that is, rural hospitals or facilities that meet certain statutory requirements) for inpatient and outpatient services and that these payments are generally based on 101 percent of reasonable cost.

- Section 1866(k) of the Act, which provides for the establishment of a quality reporting program for hospitals described in section 1886(d)(1)(B)(v) of the Act, referred to as “PPS-exempt cancer hospitals.”

- Section 1886(a)(4) of the Act, which specifies that costs of approved educational activities are excluded from the operating costs of inpatient hospital services. Hospitals with approved graduate medical education (GME) programs are paid for the direct costs of GME in accordance with section 1886(h) of the Act.

- Section 1886(b)(3)(B)(viii) of the Act, which requires the Secretary to reduce the applicable percentage increase that would otherwise apply to the standardized amount applicable to a subsection (d) hospital for discharges occurring in a fiscal year if the hospital does not submit data on measures in a form and manner, and at a time, specified by the Secretary.

- Section 1886(o) of the Act, which requires the Secretary to establish a Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Program, under which value-based incentive payments are made in a fiscal year to hospitals meeting performance standards established for a performance period for such fiscal year.

- Section 1886(p) of the Act, which establishes a Hospital-Acquired Condition (HAC) Reduction Program, under which payments to applicable hospitals are adjusted to provide an incentive to reduce hospital-acquired conditions.

- Section 1886(q) of the Act, as amended by section 15002 of the 21st Century Cures Act, which establishes the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. Under the program, payments for discharges from an applicable hospital as defined under section 1886(d) of the Act will be reduced to account for certain excess readmissions. Section 15002 of the 21st Century Cures Act requires the Secretary to compare hospitals with respect to the number of their Medicare-Medicaid dual-eligible beneficiaries (dual-eligibles) in determining the extent of excess readmissions.

- Section 1886(r) of the Act, as added by section 3133 of the Affordable Care Act, which provides for a reduction to disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments under section 1886(d)(5)(F) of the Act and for a new uncompensated care payment to eligible hospitals. Specifically, section 1886(r) of the Act requires that, for fiscal year 2014 and each subsequent fiscal year, subsection (d) hospitals that would otherwise receive a DSH payment made under section 1886(d)(5)(F) of the Act will receive two separate payments: (1) 25 percent of the amount they previously would have received under section 1886(d)(5)(F) of the Act for DSH (“the empirically justified amount”), and (2) an additional payment for the DSH hospital's proportion of uncompensated care, determined as the product of three factors. These three factors are: (1) 75 percent of the payments that would otherwise be made under section 1886(d)(5)(F) of the Act; (2) 1 minus the percent change in the percent of individuals who are uninsured; and (3) a hospital's uncompensated care amount relative to the uncompensated care amount of all DSH hospitals expressed as a percentage.

- Section 1886(m)(6) of the Act, as added by section 1206(a)(1) of the Pathway for Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) Reform Act of 2013 (Pub. L. 113-67) and amended by section 51005(a) of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (Pub. L. 115-123), which provided for the establishment of site neutral payment rate criteria under the LTCH PPS, with implementation beginning in FY 2016, and provides for a 4-year transitional blended payment rate for discharges occurring in LTCH cost reporting periods beginning in FYs 2016 through 2019. Section 51005(b) of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 amended section 1886(m)(6)(B) by adding new clause (iv), which specifies that the IPPS comparable amount defined in clause (ii)(I) shall be reduced by 4.6 percent for FYs 2018 through 2026.

- Section 1899B of the Act, as added by section 2(a) of the Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation Act of 2014 (IMPACT Act) (Pub. L. 113-185), which provides for the establishment of standardized data reporting for certain post-acute care providers, including LTCHs.

2. Summary of the Major Provisions

In this final rule, we provide a summary of the major provisions in this FY 2020 IPPS/LTCH PPS final rule. In general, these major provisions are part of the annual update to the payment policies and payment rates, consistent with the applicable statutory provisions. A general summary of the proposed changes that were included in the FY 2020 IPPS/LTCH PPS proposed rule is presented in section I.D. of the preamble of this final rule.

a. MS-DRG Documentation and Coding Adjustment

Section 631 of the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA, Pub. L. 112-240) amended section 7(b)(1)(B) of Public Law 110-90 to require the Secretary to make a recoupment adjustment to the standardized amount of Medicare payments to acute care hospitals to account for changes in MS-DRG documentation and coding that do not reflect real changes in case-mix, totaling $11 billion over a 4-year period of FYs 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017. The FY 2014 through FY 2017 adjustments represented the amount of the increase in aggregate payments as a result of not completing the prospective adjustment authorized under section 7(b)(1)(A) of Public Law 110-90 until FY 2013. Prior to the ATRA, this amount could not have been recovered under Public Law 110-90. Section 414 of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) (Pub. L. 114-10) replaced the single positive adjustment we intended to make in FY 2018 with a 0.5 percent positive adjustment to the standardized amount of Medicare payments to acute care hospitals for FYs 2018 through 2023. (The FY 2018 adjustment was subsequently adjusted to 0.4588 percent by section 15005 of the 21st Century Cures Act.) Therefore, for FY 2020, we are making an adjustment of +0.5 percent to the standardized amount.

b. Revisions and Clarifications to the New Technology Add-On Payment Policy Substantial Clinical Improvement Criterion Under the IPPS

In the proposed rule, in addition to a broad request for public comments for potential rulemaking in future years, in order to respond to stakeholder feedback requesting greater understanding of CMS' approach to evaluating substantial clinical improvement, we solicited public comments on specific changes or clarifications to the IPPS and Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) substantial clinical improvement criterion used to evaluate applications for new technology add-on payments under the IPPS and the transitional pass-through payment for additional costs of innovative devices under the OPPS that CMS might consider making in this FY 2020 IPPS/LTCH PPS final rule for applications received beginning in FY 2020 for the IPPS and CY 2020 for the OPPS, to provide greater clarity and predictability.

In this final rule, after consideration of public comments, we are revising and clarifying certain aspects of our evaluation of the substantial clinical improvement criterion under the IPPS in 42 CFR 412.87.

c. Alternative Inpatient New Technology Add-On Payment Pathway for Transformative New Devices and Antimicrobial Resistant Products

As discussed in section III.H.8. of the preamble of this final rule, after consideration of public comments, given the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA's) expedited programs, and consistent with the Administration's commitment to addressing barriers to health care innovation and ensuring that Medicare beneficiaries have access to critical and life-saving new cures and technologies that improve beneficiary health outcomes, we are adopting an alternative pathway for the inpatient new technology add-on payment for certain transformative medical devices. In situations where a new medical device has received FDA marketing authorization (that is, the device has received pre-market approval (PMA); 510(k) clearance; or the granting of a De Novo classification request) and is the subject of the FDA's Breakthrough Devices Program, we are finalizing our proposal to create an alternative inpatient new technology add-on payment pathway to facilitate access to this technology for Medicare beneficiaries. In addition, after consideration of public comments and concerns related to antimicrobial resistance and its serious impact on Medicare beneficiaries and public health overall, we are finalizing an alternative inpatient new technology add-for Qualified Infectious Disease Products (QIDPs).

Specifically, we are establishing that, for applications received for IPPS new technology add-on payments for FY 2021 and subsequent fiscal years, if a medical device is the subject of the FDA's Breakthrough Devices Program or if a medical product technology receives the FDA's QIDP designation and received FDA marketing authorization, such a device or product will be considered new and not substantially similar to an existing technology for purposes of new technology add-on payment under the IPPS. We are also establishing that the medical device or product will not need to meet the requirement under 42 CFR 412.87(b)(1) that it represent an advance that substantially improves, relative to technologies previously available, the diagnosis or treatment of Medicare beneficiaries.

d. Revision of the Calculation of the Inpatient Hospital New Technology Add-On Payment

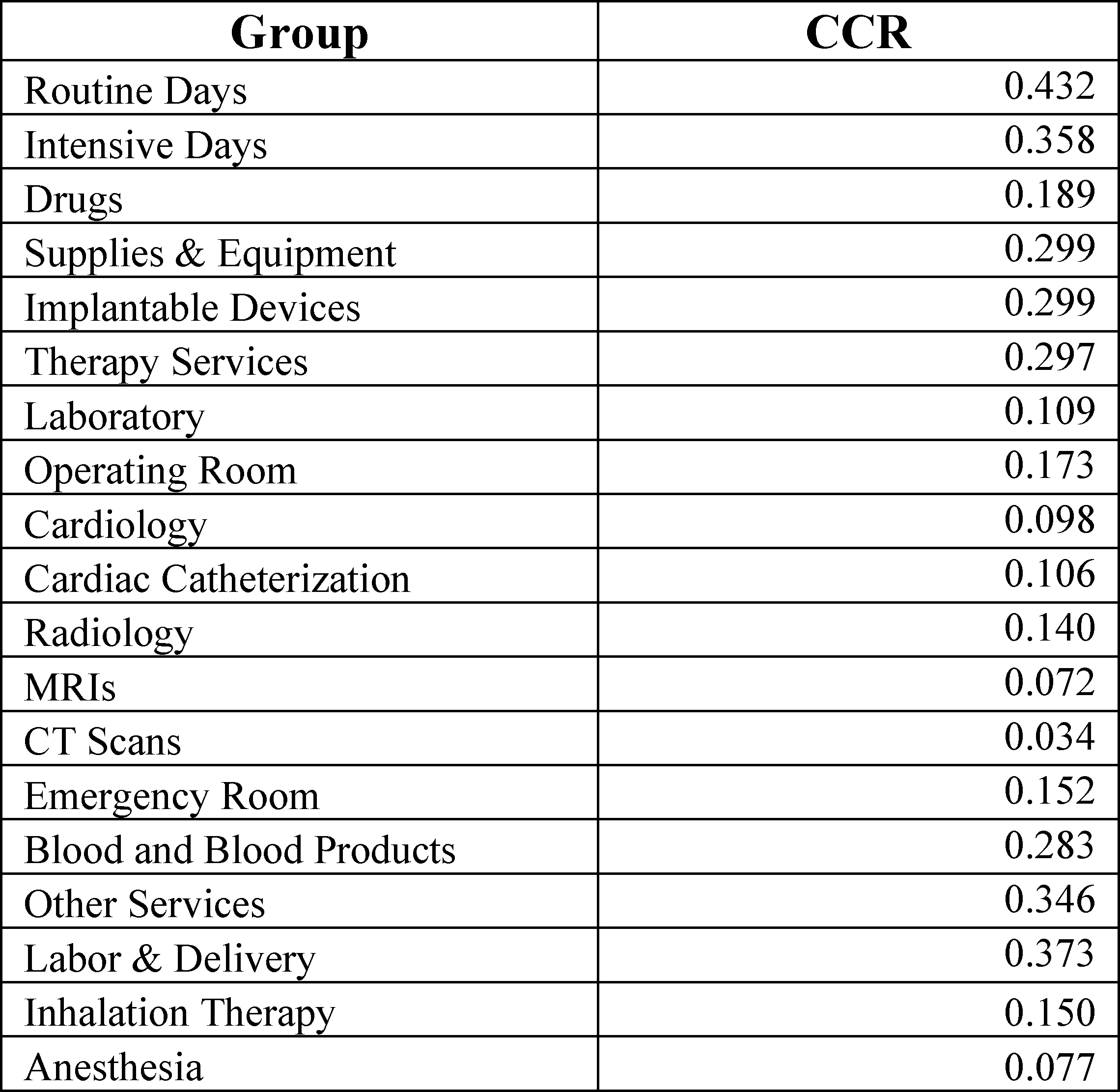

The current calculation of the new technology add-on payment is based on the cost to hospitals for the new medical service or technology. Under § 412.88, if the costs of the discharge (determined by applying cost-to-charge ratios (CCRs), as described in § 412.84(h)) exceed the full DRG payment (including payments for IME and DSH, but excluding outlier payments), Medicare will make an add-on payment equal to the lesser of: (1) 50 percent of the costs of the new medical service or technology; or (2) 50 percent of the amount by which the costs of the case exceed the standard DRG payment. Unless the discharge qualifies for an outlier payment, the additional Medicare payment is limited to the full MS-DRG payment plus 50 percent of the estimated costs of the new technology or medical service.

As discussed in section III.H.9. of the preamble of this final rule, after consideration of the concerns raised by commenters and other stakeholders, we agree that capping the add-on payment amount at 50 percent could, in some cases, not adequately reflect the costs of new technology or sufficiently support healthcare innovations.

After consideration of public comments, we are finalizing the proposed modification to the current payment amount to increase the maximum add-on payment amount to 65 percent of the costs of the new technology or medical service (except with respect to a medical product designated by the FDA as a QIDP). Therefore, we are establishing that, beginning with discharges occurring on or after October 1, 2019, for a new technology other than a medical product designated as a QIDP by the FDA, if the costs of a discharge involving a new medical service or technology exceed the full DRG payment (including payments for IME and DSH, but excluding outlier payments), Medicare will make an add-on payment equal to the lesser of: (1) 65 percent of the costs of the new medical service or technology; or (2) 65 percent of the amount by which the costs of the case exceed the standard DRG payment. In addition, after consideration of public comments and concerns related to antimicrobial resistance and its serious impact on Medicare beneficiaries and public health overall, we are establishing that, beginning with discharges occurring on or after October 1, 2019, for a new technology that is a medical product designated as a QIDP by the FDA, if the costs of a discharge involving a new medical service or technology exceed the full DRG payment (including payments for IME and DSH, but excluding outlier payments), Medicare will make an add-on payment equal to the lesser of: (1) 75 percent of the costs of the new medical service or technology; or (2) 75 percent of the amount by which the costs of the case exceed the standard DRG payment.

e. Finalized Policies To Address Wage Index Disparities

In the FY 2019 IPPS/LTCH PPS proposed rule (83 FR 20372), we invited the public to submit further comments, suggestions, and recommendations for regulatory and policy changes to the Medicare wage index. Many of the responses received from this request for information (RFI) reflect a common concern that the current wage index system perpetuates and exacerbates the disparities between high and low wage index hospitals. Many respondents also expressed concern that the calculation of the rural floor has allowed a limited number of States to manipulate the wage index system to achieve higher wages for many urban hospitals in those States at the expense of hospitals in other States, which also contributes to wage index disparities.

To help mitigate these wage index disparities, including those resulting from the inclusion of hospitals with rural reclassifications under 42 CFR 412.103 in the rural floor, in this final rule, we are reducing the disparity between high and low wage index hospitals by increasing the wage index values for certain hospitals with low wage index values and doing so in a budget neutral manner through an adjustment applied to the standardized amounts for all hospitals, as well as changing the calculation of the rural floor. We also are providing for a transition for hospitals experiencing significant decreases in their wage index values as compared to their final FY 2019 wage index. We are making these changes in a budget neutral manner.

In this final rule, we are increasing the wage index for hospitals with a wage index value below the 25th percentile wage index value for a fiscal year by half the difference between the otherwise applicable final wage index value for a year for that hospital and the 25th percentile wage index value for that year across all hospitals. Furthermore, this policy will be effective for at least 4 years, beginning in FY 2020, in order to allow employee compensation increases implemented by these hospitals sufficient time to be reflected in the wage index calculation. In order to offset the estimated increase in IPPS payments to hospitals with wage index values below the 25th percentile wage index value, we are applying a uniform budget neutrality factor to the standardized amount.

In addition, we are removing urban to rural reclassifications from the calculation of the rural floor, such that, beginning in FY 2020, the rural floor is calculated without including the wage data of hospitals that have reclassified as rural under section 1886(d)(8)(E) of the Act (as implemented in the regulations at § 412.103). Also, for the purposes of applying the provisions of section 1886(d)(8)(C)(iii) of the Act, we are removing urban to rural reclassifications from the calculation of “the wage index for rural areas in the State in which the county is located” as referred to in the statute.

Lastly, for FY 2020, we are placing a 5-percent cap on any decrease in a hospital's wage index from the hospital's final wage index in FY 2019. We are applying a budget neutrality adjustment to the standardized amount so that our transition for hospitals that could be negatively impacted is implemented in a budget neutral manner.

f. DSH Payment Adjustment and Additional Payment for Uncompensated Care

Section 3133 of the Affordable Care Act modified the Medicare disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payment methodology, beginning in FY 2014. Under section 1886(r) of the Act, which was added by section 3133 of the Affordable Care Act, starting in FY 2014, DSHs receive 25 percent of the amount they previously would have received under the statutory formula for Medicare DSH payments in section 1886(d)(5)(F) of the Act. The remaining amount, equal to 75 percent of the amount that otherwise would have been paid as Medicare DSH payments, is paid as additional payments after the amount is reduced for changes in the percentage of individuals that are uninsured. Each Medicare DSH will receive an additional payment based on its share of the total amount of uncompensated care for all Medicare DSHs for a given time period.

In this FY 2020 IPPS/LTCH PPS final rule, we have updated our estimates of the three factors used to determine uncompensated care payments for FY 2020. We continue to use uninsured estimates produced by CMS' Office of the Actuary (OACT), as part of the development of the National Health Expenditure Accounts (NHEA) in the calculation of Factor 2. We also are using a single year of data on uncompensated care costs from Worksheet S-10 for FY 2015 to determine Factor 3 for FY 2020. In addition, we are continuing to use only data regarding low-income insured days (Medicaid days for FY 2013 and FY 2017 SSI days) to determine the amount of uncompensated care payments for Puerto Rico hospitals, and Indian Health Service and Tribal hospitals. We did not adopt specific Factor 3 polices for all-inclusive rate providers for FY 2020. In this final rule, we also are continuing to use the following established policies: (1) For providers with multiple cost reports, beginning in the same fiscal year, to use the longest cost report and annualize Medicaid data and uncompensated care data if a hospital's cost report does not equal 12 months of data; (2) in the rare case where a provider has multiple cost reports beginning in the same fiscal year, but one report also spans the entirety of the following fiscal year, such that the hospital has no cost report for that fiscal year, to use the cost report that spans both fiscal years for the latter fiscal year; and (3) to apply statistical trim methodologies to potentially aberrant cost-to-charge ratios (CCRs) and potentially aberrant uncompensated care costs reported on the Worksheet S-10.

g. Changes to the LTCH PPS

In this FY 2020 IPPS/LTCH PPS final rule, we set forth changes to the LTCH PPS Federal payment rates, factors, and other payment rate policies under the LTCH PPS for FY 2020. We also are establishing the payment adjustment for LTCH discharges when the LTCH does not meet the applicable discharge payment percentage and a reinstatement process, as required by section 1886(m)(6)(C) of the Act. An LTCH will be subject to this payment adjustment if, for cost reporting periods beginning in FY 2020 and subsequent fiscal years, the LTCH's percentage of Medicare discharges that meet the criteria for exclusion from the site neutral payment rate (that is, discharges paid the LTCH PPS standard Federal payment rate) of its total number of Medicare FFS discharges paid under the LTCH PPS during the cost reporting period is not at least 50 percent. We are adopting a probationary cure period as part of the reinstatement process.

h. Reduction of Hospital Payments for Excess Readmissions

We are making changes to policies for the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, which was established under section 1886(q) of the Act, as amended by section 15002 of the 21st Century Cures Act. The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program requires a reduction to a hospital's base operating DRG payment to account for excess readmissions of selected applicable conditions. For FY 2017 and subsequent years, the reduction is based on a hospital's risk-adjusted readmission rate during a 3-year period for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure (HF), pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), elective primary total hip arthroplasty/total knee arthroplasty (THA/TKA), and coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. In this FY 2020 IPPS/LTCH PPS final rule, we are establishing the following policies: (1) A measure removal policy that aligns with the removal factor policies previously adopted in other quality reporting and quality payment programs; (2) an update to the Program's definition of “dual-eligible,” beginning with the FY 2021 program year to allow for a 1-month lookback period in data sourced from the State Medicare Modernization Act (MMA) files to determine dual-eligible status for beneficiaries who die in the month of discharge; (3) a subregulatory process to address any potential future nonsubstantive changes to the payment adjustment factor components; and (4) an update to the Program's regulations at 42 CFR 412.152 and 412.154 to reflect policies we are finalizing in this final rule and to codify additional previously finalized policies.

i. Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Program

Section 1886(o) of the Act requires the Secretary to establish a Hospital VBP Program under which value-based incentive payments are made in a fiscal year to hospitals based on their performance on measures established for a performance period for such fiscal year. In this FY 2020 IPPS/LTCH PPS final rule, we are establishing that the Hospital VBP Program will use the same data used by the HAC Reduction Program for purposes of calculating the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Health Safety Network (NHSN) Healthcare-Associated Infection (HAI) measures beginning with CY 2020 data collection, which is when the Hospital IQR Program will no longer collect data on those measures, and will rely on HAC Reduction Program validation to ensure the accuracy of CDC NHSN HAI measure data used in the Hospital VBP Program. We also are newly establishing certain performance standards.

j. Hospital-Acquired Condition (HAC) Reduction Program

Section 1886(p) of the Act establishes an incentive to hospitals to reduce the incidence of hospital-acquired conditions by requiring the Secretary to make an adjustment to payments to applicable hospitals, effective for discharges beginning on October 1, 2014. This 1-percent payment reduction applies to hospitals that rank in the worst-performing quartile (25 percent) of all applicable hospitals, relative to the national average, of conditions acquired during the applicable period and on all of the hospital's discharges for the specified fiscal year. As part of our agency-wide Patients over Paperwork and Meaningful Measures Initiatives, discussed in section I.A.2. of the FY 2019 IPPS/LTCH PPS final rule (83 FR 41147 and 41148), we are: (1) Adopting a measure removal policy that aligns with the removal factor policies previously adopted in other quality reporting and quality payment programs; (2) clarifying administrative policies for validation of the CDC NHSN HAI measures; (3) adopting the data collection periods for the FY 2022 program year; and (4) updating 42 CFR 412.172(f) to reflect policies finalized in the FY 2019 IPPS/LTCH PPS final rule.

k. Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program

Under section 1886(b)(3)(B)(viii) of the Act, subsection (d) hospitals are required to report data on measures selected by the Secretary for a fiscal year in order to receive the full annual percentage increase that would otherwise apply to the standardized amount applicable to discharges occurring in that fiscal year.

In this FY 2020 IPPS/LTCH PPS final rule, we are making several changes. We are: (1) Adopting the Safe Use of Opioids—Concurrent Prescribing eCQM beginning with the CY 2021 reporting period/FY 2023 payment determination with a clarification and update; (2) adopting the Hybrid Hospital-Wide All-Cause Readmission (Hybrid HWR) measure (NQF #2879) in a stepwise fashion, beginning with two voluntary reporting periods which will run from July 1, 2021 through June 30, 2022, and from July 1, 2022 through June 30, 2023, before requiring reporting of the measure for the reporting period that will run from July 1, 2023 through June 30, 2024, impacting the FY 2026 payment determination and for subsequent years; and (3) removing the Claims-Based Hospital-Wide All-Cause Unplanned Readmission Measure (NQF #1789) (HWR claims-only measure), beginning with the FY 2026 payment determination. We are not finalizing our proposal to adopt the Hospital Harm—Opioid-Related Adverse Events eCQM. We also are establishing reporting and submission requirements for eCQMs, including policies to: (1) Extend current eCQM reporting and submission requirements for both the CY 2020 reporting period/FY 2022 payment determination and CY 2021 reporting period/FY 2023 payment determination; (2) change the eCQM reporting and submission requirements for the CY 2022 reporting period/FY 2024 payment determination, such that hospitals will be required to report one, self-selected calendar quarter of data for three self-selected eCQMs and the Safe Use of Opioids—Concurrent Prescribing eCQM (NQF #3316e), for a total of four eCQMs; and (3) continue requiring that EHRs be certified to all available eCQMs used in the Hospital IQR Program for the CY 2020 reporting period/FY 2022 payment determination and subsequent years. These eCQM reporting and submission policies are in alignment with policies under the Promoting Interoperability Program. We also are establishing reporting and submission requirements for the Hybrid HWR measure. In addition, we are summarizing public comments we received on three measures we are considering for potential future inclusion in the Hospital IQR Program.

l. Medicare and Medicaid Promoting Interoperability Programs

For purposes of an increased level of stability, reducing the burden on eligible hospitals and CAHs, and clarifying certain existing policies, we are finalizing several changes to the Promoting Interoperability Program. Specifically, we are: (1) Eliminating the requirement that, for the FY 2020 payment adjustment year, for an eligible hospital that has not successfully demonstrated it is a meaningful EHR user in a prior year, the EHR reporting period in CY 2019 must end before and the eligible hospital must successfully register for and attest to meaningful use no later than the October 1, 2019 deadline; (2) establishing an EHR reporting period of a minimum of any continuous 90-day period in CY 2021 for new and returning participants (eligible hospitals and CAHs) in the Medicare Promoting Interoperability Program attesting to CMS; (3) requiring that the Medicare Promoting Interoperability Program measure actions must occur within the EHR reporting period, beginning with the EHR reporting period in CY 2020; (4) revising the Query of PDMP measure to make it an optional measure worth 5 bonus points in CY 2020, removing the exclusions associated with this measure in CY 2020, requiring a yes/no response instead of a numerator and denominator for CY 2019 and CY 2020, and clearly stating our intended policy that the measure is worth a full 5 bonus points in CY 2019 and CY 2020; (5) changing the maximum points available for the e-Prescribing measure from 5 points to 10 points beginning in CY 2020; (6) removing the Verify Opioid Treatment Agreement measure beginning in CY 2020 and clearly stating our intended policy that this measure is worth a full 5 bonus points in CY 2019; and (7) revising the Support Electronic Referral Loops by Receiving and Incorporating Health Information measure to more clearly capture the previously established policy regarding CEHRT use. We also are amending our regulations to incorporate several of these finalized policies.

For CQM reporting under the Medicare and Medicaid Promoting Interoperability Programs, we are generally aligning our requirements with requirements under the Hospital IQR Program. Specifically, we are: (1) Adopting one opioid-related CQM (Safe Use of Opioids—Concurrent Prescribing CQM beginning with the reporting period in CY 2021 (we are not finalizing our proposal to add the Hospital Harm—Opioid-Related Adverse Events CQM); (2) extending current CQM reporting and submission requirements for the reporting periods in CY 2020 and CY 2021; and (3) establishing CQM reporting and submission requirements for the reporting period in CY 2022, which will require all eligible hospitals and CAHs to report on the Safe Use of Opioids—Concurrent Prescribing eCQM beginning with the reporting period in CY 2022.

We sought public comments on whether we should consider proposing to adopt in future rulemaking the Hybrid Hospital-Wide All-Cause Readmission (Hybrid HWR) measure, beginning with the reporting period in CY 2023, a measure which we adopted under the Hospital IQR Program, and we sought information on a variety of issues regarding the future direction of the Medicare and Medicaid Promoting Interoperability Programs. We may use the input we received to inform further rulemaking.

3. Summary of Costs and Benefits

- Adjustment for MS-DRG Documentation and Coding Changes. Section 414 of the MACRA replaced the single positive adjustment we intended to make in FY 2018 once the recoupment required by section 631 of the ATRA was complete with a 0.5 percentage point positive adjustment to the standardized amount of Medicare payments to acute care hospitals for FYs 2018 through 2023. (The FY 2018 adjustment was subsequently adjusted to 0.4588 percentage point by section 15005 of the 21st Century Cures Act.) For FY 2020, we are making an adjustment of +0.5 percentage point to the standardized amount consistent with the MACRA.

- Alternative Inpatient New Technology Add-On Payment Pathway for Transformative New Devices: In this FY 2020 IPPS/LTCH PPS final rule, we are establishing an alternative inpatient new technology add-on payment pathway for a new medical device that is subject to the FDA Breakthrough Devices Program and has received FDA authorization (that is, received PMA approval, 510(k) clearance, or the granting of De Novo classification request). We are also establishing that, if a medical product is designated by the FDA as a Qualified Infectious Disease Product (QIDP) and received FDA market authorization. Under these alternative inpatient new technology add-on payment pathways, such a medical device or product will be considered new and not substantially similar to an existing technology for purposes of new technology add-on payment under the IPPS, and such a medical product or device will not need to meet the requirement under § 412.87(b)(1) that it represent an advance that substantially improves, relative to technologies previously available, the diagnosis or treatment of Medicare beneficiaries.

Given the relatively recent introduction of FDA's Breakthrough Devices Program, there have not been any medical devices that were part of the Breakthrough Devices Program and received FDA marketing authorization and for which the applicant applied for a new technology add-on payment under the IPPS and was not approved. If all of the future new medical devices that were part of the Breakthrough Devices Program and QIDPs that would have applied for new technology add-on payments would have been approved under the existing criteria, this policy has no impact. To the extent that there are future medical devices that were part of the Breakthrough Devices Program or QIDPs that are the subject of applications for new technology add-on payments, and those applications would have been denied under the current new technology add-on payment criteria, this policy is a cost, but that cost is not estimable. Therefore, it is not possible to quantify the impact of this policy.

Revisions to the Calculation of the Inpatient Hospital New Technology Add-On Payment: The current calculation of the new technology add-on payment is based on the cost to hospitals for the new medical service or technology. Under existing § 412.88, if the costs of the discharge exceed the full DRG payment (including payments for IME and DSH, but excluding outlier payments), Medicare makes an add-on payment equal to the lesser of: (1) 50 percent of the estimated costs of the new technology or medical service; or (2) 50 percent of the amount by which the costs of the case exceed the standard DRG payment.

As discussed in section II.H.9. of the preamble of this final rule, we have modified the current payment mechanism to increase the amount of the maximum add-on payment amount to 65 percent (and 75 percent for QIDPs). Specifically, for technologies other than QIDPs, if the costs of a discharge (determined by applying CCRs as described in § 412.84(h)) exceed the full DRG payment (including payments for IME and DSH, but excluding outlier payments), Medicare will make an add-on payment equal to the lesser of: (1) 65 percent (or 75 percent for QIDPs) of the costs of the new medical service or technology; or (2) 65 percent (75 percent for QIDPs) of the amount by which the costs of the case exceed the standard DRG payment.

We estimate that for the nine technologies for which we are continuing to make new technology add on payments in FY 2020 and for the nine FY 2020 new technology add-on payment applications that we are approving for new technology add-on payments for FY 2020, these changes to the calculation of the new technology add-on payment will increase IPPS spending by approximately $94 million in FY 2020.

Technologies Approved for FY 2020 New Technology Add-On Payments: In section II.H.5. of the preamble to this final rule, we discuss 13 technologies for which we received applications for add-on payments for new medical services and technologies for FY 2020. We also discuss the status of the new technologies that were approved to receive new technology add-on payments in FY 2019 in section II.H.4. of the preamble to this final rule. As explained in the preamble to this final rule, add-on payments for new medical services and technologies under section 1886(d)(5)(K) of the Act are not required to be budget neutral. Based on those technologies approved for new technology add-on payments for FY 2020, new technology add-on payment are projected to increase approximately $162 million as compared to FY 2019 (which also reflects the estimated changes to the calculation of the inpatient new technology add-on payment described above).

- Changes To Address Wage Index Disparities. As discussed in section III.N. of the preamble of this final rule, to help mitigate wage index disparities, including those resulting from the inclusion of hospitals with rural reclassifications under 42 CFR 412.103 in the rural floor, we are reducing the disparity between high and low wage index hospitals by increasing the wage index values for certain hospitals with low wage index values (that is, hospitals with wage index values below the 25th percentile wage index value across all hospitals), as well as changing the calculation of the rural floor. In order to offset the estimated increase in IPPS payments to hospitals with wage index values below the 25th percentile wage index value, we have applied a uniform budget neutrality adjustment to the standardized amount. We also are establishing a transition for FY 2020 for hospitals experiencing significant decreases in their wage index values, and we are implementing this in a budget neutral manner by applying a budget neutrality adjustment to the standardized amount.

- Medicare DSH Payment Adjustment and Additional Payment for Uncompensated Care. For FY 2020, we are updating our estimates of the three factors used to determine uncompensated care payments. We are continuing to use uninsured estimates produced by OACT, as part of the development of the NHEA in the calculation of Factor 2. We also are using a single year of data on uncompensated care costs from Worksheet S-10 for FY 2015 to determine Factor 3 for FY 2020. To determine the amount of uncompensated care for purposes of calculating Factor 3 for Puerto Rico hospitals and Indian Health Service and Tribal hospitals, we are continuing to use only data regarding low-income insured days (Medicaid days for FY 2013 and FY 2017 SSI days).

We project that the amount available to distribute as payments for uncompensated care for FY 2020 will increase by approximately $78 million, as compared to our estimate of the uncompensated care payments that will be distributed in FY 2019. The payments have redistributive effects, based on a hospital's uncompensated care amount relative to the uncompensated care amount for all hospitals that are projected to be eligible to receive Medicare DSH payments, and the calculated payment amount is not directly tied to a hospital's number of discharges.

Update to the LTCH PPS Payment Rates and Other Payment Policies. Based on the best available data for the 384 LTCHs in our database, we estimate that the changes to the payment rates and factors that we presented in the preamble of and Addendum to this FY 2020 IPPS/LTCH PPS final rule, which reflect the end of the transition of the statutory application of the site neutral payment rate and the update to the LTCH PPS standard Federal payment rate for FY 2020, will result in an estimated increase in payments in FY 2020 of approximately $43 million.

- Changes to the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. For FY 2020 and subsequent years, the reduction is based on a hospital's risk-adjusted readmission rate during a 3-year period for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure (HF), pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), elective primary total hip arthroplasty/total knee arthroplasty (THA/TKA), and coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. Overall, in this FY 2020 IPPS/LTCH PPS final rule, we estimate that 2,583 hospitals would have their base operating DRG payments reduced by their determined proxy FY 2020 hospital-specific readmission adjustment. As a result, we estimate that the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program will save approximately $563 million in FY 2020.

- Value-Based Incentive Payments Under the Hospital VBP Program. We estimate that there will be no net financial impact to participating hospitals under the Hospital VBP Program for the FY 2020 program year in the aggregate because, by law, the amount available for value-based incentive payments under the program in a given year must be equal to the total amount of base operating MS-DRG payment amount reductions for that year, as estimated by the Secretary. The estimated amount of base operating MS-DRG payment amount reductions for the FY 2020 program year and, therefore, the estimated amount available for value-based incentive payments for FY 2020 discharges is approximately $1.9 billion.

- Changes to the HAC Reduction Program. A hospital's Total HAC score and its ranking in comparison to other hospitals in any given year depend on several different factors. The FY 2020 program year is the first year in which we are implementing our equal measure weights scoring methodology. Any significant impact due to the HAC Reduction Program changes for FY 2020, including which hospitals will receive the adjustment, will depend on the actual experience of hospitals in the Program. We also are updating the hourly wage rate associated with burden for CDC NHSN HAI validation under the HAC Reduction Program.

- Changes to the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program. Across 3,300 IPPS hospitals, we estimate that our changes for the Hospital IQR Program in this FY 2020 IPPS/LTCH PPS final rule would result in changes to the information collection burden compared to previously adopted requirements. The only policy that will affect the information collection burden for the Hospital IQR Program is the policy to adopt the Hybrid Hospital-Wide All-Cause Readmission (Hybrid HWR) measure (NQF #2879) in a stepwise fashion, beginning with two voluntary reporting periods which will run from July 1, 2021 through June 30, 2022, and from July 1, 2022 through June 30, 2023, before requiring reporting of the measure for the reporting period that will run from July 1, 2023 through June 30, 2024, impacting the FY 2026 payment determination and for subsequent years. We estimate that the impact of this change is a total collection of information burden increase of 2,211 hours and a total cost increase of approximately $83,266 for all participating IPPS hospitals annually.

- Changes to the Medicare and Medicaid Promoting Interoperability Programs. We believe that, overall, the revised policies in this FY 2020 IPPS/LTCH PPS final rule will reduce burden, as described in detail in section X.B.9. of the preamble and Appendix A, section I.N. of this final rule.

B. Background Summary

1. Acute Care Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS)

Section 1886(d) of the Social Security Act (the Act) sets forth a system of payment for the operating costs of acute care hospital inpatient stays under Medicare Part A (Hospital Insurance) based on prospectively set rates. Section 1886(g) of the Act requires the Secretary to use a prospective payment system (PPS) to pay for the capital-related costs of inpatient hospital services for these “subsection (d) hospitals.” Under these PPSs, Medicare payment for hospital inpatient operating and capital-related costs is made at predetermined, specific rates for each hospital discharge. Discharges are classified according to a list of diagnosis-related groups (DRGs).

The base payment rate is comprised of a standardized amount that is divided into a labor-related share and a nonlabor-related share. The labor-related share is adjusted by the wage index applicable to the area where the hospital is located. If the hospital is located in Alaska or Hawaii, the nonlabor-related share is adjusted by a cost-of-living adjustment factor. This base payment rate is multiplied by the DRG relative weight.

If the hospital treats a high percentage of certain low-income patients, it receives a percentage add-on payment applied to the DRG-adjusted base payment rate. This add-on payment, known as the disproportionate share hospital (DSH) adjustment, provides for a percentage increase in Medicare payments to hospitals that qualify under either of two statutory formulas designed to identify hospitals that serve a disproportionate share of low-income patients. For qualifying hospitals, the amount of this adjustment varies based on the outcome of the statutory calculations. The Affordable Care Act revised the Medicare DSH payment methodology and provides for a new additional Medicare payment beginning on October 1, 2013, that considers the amount of uncompensated care furnished by the hospital relative to all other qualifying hospitals.

If the hospital is training residents in an approved residency program(s), it receives a percentage add-on payment for each case paid under the IPPS, known as the indirect medical education (IME) adjustment. This percentage varies, depending on the ratio of residents to beds.

Additional payments may be made for cases that involve new technologies or medical services that have been approved for special add-on payments. To qualify, a new technology or medical service must demonstrate that it is a substantial clinical improvement over technologies or services otherwise available, and that, absent an add-on payment, it would be inadequately paid under the regular DRG payment.

The costs incurred by the hospital for a case are evaluated to determine whether the hospital is eligible for an additional payment as an outlier case. This additional payment is designed to protect the hospital from large financial losses due to unusually expensive cases. Any eligible outlier payment is added to the DRG-adjusted base payment rate, plus any DSH, IME, and new technology or medical service add-on adjustments.

Although payments to most hospitals under the IPPS are made on the basis of the standardized amounts, some categories of hospitals are paid in whole or in part based on their hospital-specific rate, which is determined from their costs in a base year. For example, sole community hospitals (SCHs) receive the higher of a hospital-specific rate based on their costs in a base year (the highest of FY 1982, FY 1987, FY 1996, or FY 2006) or the IPPS Federal rate based on the standardized amount. SCHs are the sole source of care in their areas. Specifically, section 1886(d)(5)(D)(iii) of the Act defines an SCH as a hospital that is located more than 35 road miles from another hospital or that, by reason of factors such as an isolated location, weather conditions, travel conditions, or absence of other like hospitals (as determined by the Secretary), is the sole source of hospital inpatient services reasonably available to Medicare beneficiaries. In addition, certain rural hospitals previously designated by the Secretary as essential access community hospitals are considered SCHs.

Under current law, the Medicare-dependent, small rural hospital (MDH) program is effective through FY 2022. Through and including FY 2006, an MDH received the higher of the Federal rate or the Federal rate plus 50 percent of the amount by which the Federal rate was exceeded by the higher of its FY 1982 or FY 1987 hospital-specific rate. For discharges occurring on or after October 1, 2007, but before October 1, 2022, an MDH receives the higher of the Federal rate or the Federal rate plus 75 percent of the amount by which the Federal rate is exceeded by the highest of its FY 1982, FY 1987, or FY 2002 hospital-specific rate. MDHs are a major source of care for Medicare beneficiaries in their areas. Section 1886(d)(5)(G)(iv) of the Act defines an MDH as a hospital that is located in a rural area (or, as amended by the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, a hospital located in a State with no rural area that meets certain statutory criteria), has not more than 100 beds, is not an SCH, and has a high percentage of Medicare discharges (not less than 60 percent of its inpatient days or discharges in its cost reporting year beginning in FY 1987 or in two of its three most recently settled Medicare cost reporting years).

Section 1886(g) of the Act requires the Secretary to pay for the capital-related costs of inpatient hospital services in accordance with a prospective payment system established by the Secretary. The basic methodology for determining capital prospective payments is set forth in our regulations at 42 CFR 412.308 and 412.312. Under the capital IPPS, payments are adjusted by the same DRG for the case as they are under the operating IPPS. Capital IPPS payments are also adjusted for IME and DSH, similar to the adjustments made under the operating IPPS. In addition, hospitals may receive outlier payments for those cases that have unusually high costs.

The existing regulations governing payments to hospitals under the IPPS are located in 42 CFR part 412, subparts A through M.

2. Hospitals and Hospital Units Excluded From the IPPS

Under section 1886(d)(1)(B) of the Act, as amended, certain hospitals and hospital units are excluded from the IPPS. These hospitals and units are: Inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF) hospitals and units; long-term care hospitals (LTCHs); psychiatric hospitals and units; children's hospitals; cancer hospitals; extended neoplastic disease care hospitals, and hospitals located outside the 50 States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico (that is, hospitals located in the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa). Religious nonmedical health care institutions (RNHCIs) are also excluded from the IPPS. Various sections of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA, Pub. L. 105-33), the Medicare, Medicaid and SCHIP [State Children's Health Insurance Program] Balanced Budget Refinement Act of 1999 (BBRA, Pub. L. 106-113), and the Medicare, Medicaid, and SCHIP Benefits Improvement and Protection Act of 2000 (BIPA, Pub. L. 106-554) provide for the implementation of PPSs for IRF hospitals and units, LTCHs, and psychiatric hospitals and units (referred to as inpatient psychiatric facilities (IPFs)). (We note that the annual updates to the LTCH PPS are included along with the IPPS annual update in this document. Updates to the IRF PPS and IPF PPS are issued as separate documents.) Children's hospitals, cancer hospitals, hospitals located outside the 50 States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico (that is, hospitals located in the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa), and RNHCIs continue to be paid solely under a reasonable cost-based system, subject to a rate-of-increase ceiling on inpatient operating costs. Similarly, extended neoplastic disease care hospitals are paid on a reasonable cost basis, subject to a rate-of-increase ceiling on inpatient operating costs.

The existing regulations governing payments to excluded hospitals and hospital units are located in 42 CFR parts 412 and 413.

3. Long-Term Care Hospital Prospective Payment System (LTCH PPS)

The Medicare prospective payment system (PPS) for LTCHs applies to hospitals described in section 1886(d)(1)(B)(iv) of the Act, effective for cost reporting periods beginning on or after October 1, 2002. The LTCH PPS was established under the authority of sections 123 of the BBRA and section 307(b) of the BIPA (as codified under section 1886(m)(1) of the Act). During the 5-year (optional) transition period, a LTCH's payment under the PPS was based on an increasing proportion of the LTCH Federal rate with a corresponding decreasing proportion based on reasonable cost principles. Effective for cost reporting periods beginning on or after October 1, 2006 through September 30, 2015 all LTCHs were paid 100 percent of the Federal rate. Section 1206(a) of the Pathway for SGR Reform Act of 2013 (Pub. L. 113-67) established the site neutral payment rate under the LTCH PPS, which made the LTCH PPS a dual rate payment system beginning in FY 2016. Under this statute, based on a rolling effective date that is linked to the date on which a given LTCH's Federal FY 2016 cost reporting period begins, LTCHs are generally paid for discharges at the site neutral payment rate unless the discharge meets the patient criteria for payment at the LTCH PPS standard Federal payment rate. The existing regulations governing payment under the LTCH PPS are located in 42 CFR part 412, subpart O. Beginning October 1, 2009, we issue the annual updates to the LTCH PPS in the same documents that update the IPPS (73 FR 26797 through 26798).

4. Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs)

Under sections 1814(l), 1820, and 1834(g) of the Act, payments made to critical access hospitals (CAHs) (that is, rural hospitals or facilities that meet certain statutory requirements) for inpatient and outpatient services are generally based on 101 percent of reasonable cost. Reasonable cost is determined under the provisions of section 1861(v) of the Act and existing regulations under 42 CFR part 413.

5. Payments for Graduate Medical Education (GME)

Under section 1886(a)(4) of the Act, costs of approved educational activities are excluded from the operating costs of inpatient hospital services. Hospitals with approved graduate medical education (GME) programs are paid for the direct costs of GME in accordance with section 1886(h) of the Act. The amount of payment for direct GME costs for a cost reporting period is based on the hospital's number of residents in that period and the hospital's costs per resident in a base year. The existing regulations governing payments to the various types of hospitals are located in 42 CFR part 413.

C. Summary of Provisions of Recent Legislation That Are Implemented in This Final Rule

1. Pathway for SGR Reform Act of 2013 (Pub. L. 113-67)

The Pathway for SGR Reform Act of 2013 (Pub. L. 113-67) introduced new payment rules in the LTCH PPS. Under section 1206 of this law, discharges in cost reporting periods beginning on or after October 1, 2015, under the LTCH PPS, receive payment under a site neutral rate unless the discharge meets certain patient-specific criteria. In this FY 2020 IPPS/LTCH PPS final rule, we are continuing to update certain policies that implemented provisions under section 1206 of the Pathway for SGR Reform Act.

2. Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation Act of 2014 (IMPACT Act) (Pub. L. 113-185)

The Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation Act of 2014 (IMPACT Act) (Pub. L. 113-185), enacted on October 6, 2014, made a number of changes that affect the Long-Term Care Hospital Quality Reporting Program (LTCH QRP). In this final rule, we are continuing to implement portions of section 1899B of the Act, as added by section 2(a) of the IMPACT Act, which, in part, requires LTCHs, among other post-acute care providers, to report standardized patient assessment data, data on quality measures, and data on resource use and other measures.

3. The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (Pub. L. 114-10)

Section 414 of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA, Pub. L. 114-10) specifies a 0.5 percent positive adjustment to the standardized amount of Medicare payments to acute care hospitals for FYs 2018 through 2023. These adjustments follow the recoupment adjustment to the standardized amounts under section 1886(d) of the Act based upon the Secretary's estimates for discharges occurring from FYs 2014 through 2017 to fully offset $11 billion, in accordance with section 631 of the ATRA. The FY 2018 adjustment was subsequently adjusted to 0.4588 percent by section 15005 of the 21st Century Cures Act.

4. The 21st Century Cures Act (Pub. L. 114-255)

The 21st Century Cures Act (Pub. L. 114-255), enacted on December 13, 2016, contained the following provision affecting payments under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, which we are continuing to implement in this final rule:

- Section 15002, which amended section 1886(q)(3) of the Act by adding subparagraphs (D) and (E), which requires the Secretary to develop a methodology for calculating the excess readmissions adjustment factor for the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, based on cohorts defined by the percentage of dual-eligible patients (that is, patients who are eligible for both Medicare and full-benefit Medicaid coverage) cared for by a hospital. In this FY 2020 IPPS/LTCH PPS final rule, we are continuing to implement changes to the payment adjustment factor to assess penalties, based on a hospital's performance, relative to other hospitals treating a similar proportion of dual-eligible patients.

D. Issuance of Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

In the FY 2020 IPPS/LTCH PPS proposed rule appearing in the Federal Register on May 3, 2019 (84 FR 19158), we set forth proposed payment and policy changes to the Medicare IPPS for FY 2020 operating costs and capital-related costs of acute care hospitals and certain hospitals and hospital units that are excluded from IPPS. In addition, we set forth proposed changes to the payment rates, factors, and other payment and policy-related changes to programs associated with payment rate policies under the LTCH PPS for FY 2020.

In this final rule is a general summary of the changes that we proposed to make.

1. Proposed Changes to MS-DRG Classifications and Recalibrations of Relative Weights

In section II. of the preamble of the proposed rule, we included—

- Proposed changes to MS-DRG classifications based on our yearly review for FY 2020.

- Proposed adjustment to the standardized amounts under section 1886(d) of the Act for FY 2020 in accordance with the amendments made to section 7(b)(1)(B) of Public Law 110-90 by section 414 of the MACRA.

- Proposed recalibration of the MS-DRG relative weights.

- A discussion of the proposed FY 2020 status of new technologies approved for add-on payments for FY 2019 and a presentation of our evaluation and analysis of the FY 2020 applicants for add-on payments for high-cost new medical services and technologies (including public input, as directed by Pub. L. 108-173, obtained in a town hall meeting).

- A request for public comments on the substantial clinical improvement criterion used to evaluate applications for both the IPPS new technology add-on payments and the OPPS transitional pass-through payment for devices, and a discussion of potential revisions that we were considering adopting as final policies related to the substantial clinical improvement criterion for applications received beginning in FY 2020 for the IPPS (that is, for FY 2021 and later new technology add-on payments) and beginning in CY 2020 for the OPPS.

- A proposed alternative IPPS new technology add-on payment pathway for certain transformative new devices.

- Proposed changes to the calculation of the IPPS new technology add-on payment.

2. Proposed Changes to the Hospital Wage Index for Acute Care Hospitals

In section III. of the preamble to the proposed rule we proposed to make revisions to the wage index for acute care hospitals and the annual update of the wage data. Specific issues addressed included, but were not limited to, the following:

- The proposed FY 2020 wage index update using wage data from cost reporting periods beginning in FY 2016.

- Proposals to address wage index disparities between high and low wage index hospitals.

- Calculation, analysis, and implementation of the proposed occupational mix adjustment to the wage index for acute care hospitals for FY 2020 based on the 2016 Occupational Mix Survey.

- Proposed application of the rural floor and the frontier State floor.

- Proposed revisions to the wage index for acute care hospitals, based on hospital redesignations and reclassifications under sections 1886(d)(8)(B), (d)(8)(E), and (d)(10) of the Act.

- Proposed change to Lugar county assignments.

- Proposed adjustment to the wage index for acute care hospitals for FY 2020 based on commuting patterns of hospital employees who reside in a county and work in a different area with a higher wage index.

- Proposed labor-related share for the proposed FY 2020 wage index.

3. Other Decisions and Proposed Changes to the IPPS for Operating Costs

In section IV. of the preamble of the proposed rule, we discussed proposed changes or clarifications of a number of the provisions of the regulations in 42 CFR parts 412 and 413, including the following:

- Proposed changes to MS-DRGs subject to the postacute care transfer policy and special payment policy.

- Proposed changes to the inpatient hospital update for FY 2020.

- Proposed conforming changes to the regulations for the low-volume hospital payment adjustment policy.

- Proposed updated national and regional case-mix values and discharges for purposes of determining RRC status.

- The statutorily required IME adjustment factor for FY 2020.

- Proposed changes to the methodologies for determining Medicare DSH payments and the additional payments for uncompensated care.

- A request for public comments on PRRB appeals related to a hospital's Medicaid fraction in the DSH payment adjustment calculation.

- Proposed changes to the policies for payment adjustments under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program based on hospital readmission measures and the process for hospital review and correction of those rates for FY 2020.

- Proposed changes to the requirements and provision of value-based incentive payments under the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program.

- Proposed requirements for payment adjustments to hospitals under the HAC Reduction Program for FY 2020.

- Proposed changes related to CAHs as nonproviders for direct GME and IME payment purposes.

- Discussion of the implementation of the Rural Community Hospital Demonstration Program in FY 2020.

4. Proposed FY 2020 Policy Governing the IPPS for Capital-Related Costs

In section V. of the preamble to the proposed rule, we discussed the proposed payment policy requirements for capital-related costs and capital payments to hospitals for FY 2020.

5. Proposed Changes to the Payment Rates for Certain Excluded Hospitals: Rate-of-Increase Percentages

In section VI. of the preamble of the proposed rule, we discussed—

- Proposed changes to payments to certain excluded hospitals for FY 2020.

- Proposed change related to CAH payment for ambulance services.

- Proposed continued implementation of the Frontier Community Health Integration Project (FCHIP) Demonstration.

6. Proposed Changes to the LTCH PPS

In section VII. of the preamble of the is proposed rule, we set forth—

- Proposed changes to the LTCH PPS Federal payment rates, factors, and other payment rate policies under the LTCH PPS for FY 2020.

- Proposed payment adjustment for discharges of LTCHs that do not meet the applicable discharge payment percentage.

7. Proposed Changes Relating to Quality Data Reporting for Specific Providers and Suppliers

In section VIII. of the preamble of the proposed rule, we addressed—

- Proposed requirements for the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program.

- Proposed changes to the requirements for the quality reporting program for PPS-exempt cancer hospitals (PCHQR Program).

- Proposed changes to the requirements under the LTCH Quality Reporting Program (LTCH QRP).

- Proposed changes to requirements pertaining to eligible hospitals and CAHs participating in the Medicare and Medicaid Promoting Interoperability Programs.

8. Provider Reimbursement Review Board Appeals