AGENCY:

Commodity Futures Trading Commission.

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (“Commission” or “CFTC”) is adopting a final rule (“Final Rule”) addressing the cross-border application of certain swap provisions of the Commodity Exchange Act (“CEA or “Act”), as added by Title VII of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (“Dodd-Frank Act”). The Final Rule addresses the cross-border application of the registration thresholds and certain requirements applicable to swap dealers (“SDs”) and major swap participants (“MSPs”), and establishes a formal process for requesting comparability determinations for such requirements from the Commission. The Final Rule adopts a risk-based approach that, consistent with the applicable section of the CEA, and with due consideration of international comity principles and the Commission's interest in focusing its authority on potential significant risks to the U.S. financial system, advances the goals of the Dodd-Frank Act's swap reforms, while fostering greater liquidity and competitive markets, promoting enhanced regulatory cooperation, and improving the global harmonization of swap regulation.

DATES:

The Final Rule is effective November 13, 2020. Specific compliance dates are set forth in the Final Rule.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Joshua Sterling, Director, (202) 418-6056, jsterling@cftc.gov; Frank Fisanich, Chief Counsel, (202) 418-5949, ffisanich@cftc.gov; Amanda Olear, Deputy Director, (202) 418-5283, aolear@cftc.gov; Rajal Patel, Associate Director, 202-418-5261, rpatel@cftc.gov; Lauren Bennett, Special Counsel, 202-418-5290, lbennett@cftc.gov; Jacob Chachkin, Special Counsel, (202) 418-5496, jchachkin@cftc.gov; or Owen Kopon, Special Counsel, okopon@cftc.gov, 202-418-5360, Division of Swap Dealer and Intermediary Oversight (“DSIO”), Commodity Futures Trading Commission, Three Lafayette Centre, 1155 21st Street NW, Washington, DC 20581.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Table of Contents

I. Background

A. Statutory Authority and Prior Commission Action

B. Proposed Rule and Brief Summary of Comments Received

C. Global Regulatory and Market Structure

D. Interpretation of CEA Section 2(i)

1. Proposed Rule and Discussion of Comments 2. Final InterpretationE. Final Rule

II. Key Definitions

A. Reliance on Representations—Generally

B. U.S. Person, Non-U.S. Person, and United States

1. Generally 2. Prongs 3. Principal Place of Business 4. Exception for International Financial Institutions 5. Reliance on Prior Representations 6. OtherC. Guarantee

1. Proposed Rule 2. Summary of Comments 3. Final RuleD. Significant Risk Subsidiary, Significant Subsidiary, Subsidiary, Parent Entity, and U.S. GAAP

1. Proposed Rule 2. Summary of Comments 3. Final Rule and Commission ResponseE. Foreign Branch and Swap Conducted Through a Foreign Branch

1. Proposed Rule 2. Summary of Comments 3. Final Rule and Commission ResponseF. Swap Entity, U.S. Swap Entity, and Non-U.S. Swap Entity

G. U.S. Branch

H. Swap Conducted Through a U.S. Branch

1. Proposed Rule 2. Summary of Comments 3. Final Rule—Swap Booked in a U.S. BranchI. Foreign-Based Swap and Foreign Counterparty

1. Proposed Rule 2. Summary of Comments 3. Final RuleIII. Cross-Border Application of the Swap Dealer Registration Threshold

A. U.S. Persons

B. Non-U.S. Persons

1. Swaps by a Significant Risk Subsidiary 2. Swaps With a U.S. Person 3. Guaranteed SwapsC. Aggregation Requirement

D. Certain Exchange-Traded and Cleared Swaps

IV. Cross-Border Application of the Major Swap Participant Registration Tests

A. U.S. Persons

B. Non-U.S. Persons

1. Swaps by a Significant Risk Subsidiary 2. Swap Positions With a U.S. Person 3. Guaranteed Swap PositionsC. Attribution Requirement

D. Certain Exchange-Traded and Cleared Swaps

V. ANE Transactions

A. Background and Proposed Approach

B. Summary of Comments

C. Commission Determination

VI. Exceptions From Group B and Group C Requirements, Substituted Compliance for Group A and Group B Requirements, and Comparability Determinations

A. Classification and Application of Certain Regulatory Requirements—Group A, Group B, and Group C Requirements

1. Group A Requirements 2. Group B Requirements 3. Group C RequirementsB. Exceptions From Group B and Group C Requirements

1. Proposed Exceptions, Generally 2. Exchange-Traded Exception 3. Foreign Swap Group C Exception 4. Limited Foreign Branch Group B Exception 5. Non-U.S. Swap Entity Group B ExceptionC. Substituted Compliance

1. Proposed Rule 2. Summary of Comments 3. Final RuleD. Comparability Determinations

1. Standard of Review 2. Supervision of Swap Entities Relying on Substituted Compliance 3. Effect on Existing Comparability Determinations 4. Eligibility Requirements 5. Submission RequirementsVII. Recordkeeping

VIII. Other Comments

IX. Compliance Dates and Transition Issues

A. Summary of Comments

B. Commission Determination

X. Related Matters

A. Regulatory Flexibility Act

B. Paperwork Reduction Act

C. Cost-Benefit Considerations

1. Benefits

2. Assessment Costs

3. Cross-Border Application of the SD Registration Threshold

4. Cross-Border Application of the MSP Registration Thresholds

5. Monitoring Costs

6. Registration Costs

7. Programmatic Costs

8. Exceptions From Group B and Group C Requirements, Availability of Substituted Compliance, and Comparability Determinations

9. Recordkeeping

10. Alternatives Considered

11. Section 15(a) Factors

D. Antitrust Laws

XI. Preamble Summary Tables

A. Table A—Cross-Border Application of the SD De Minimis Threshold

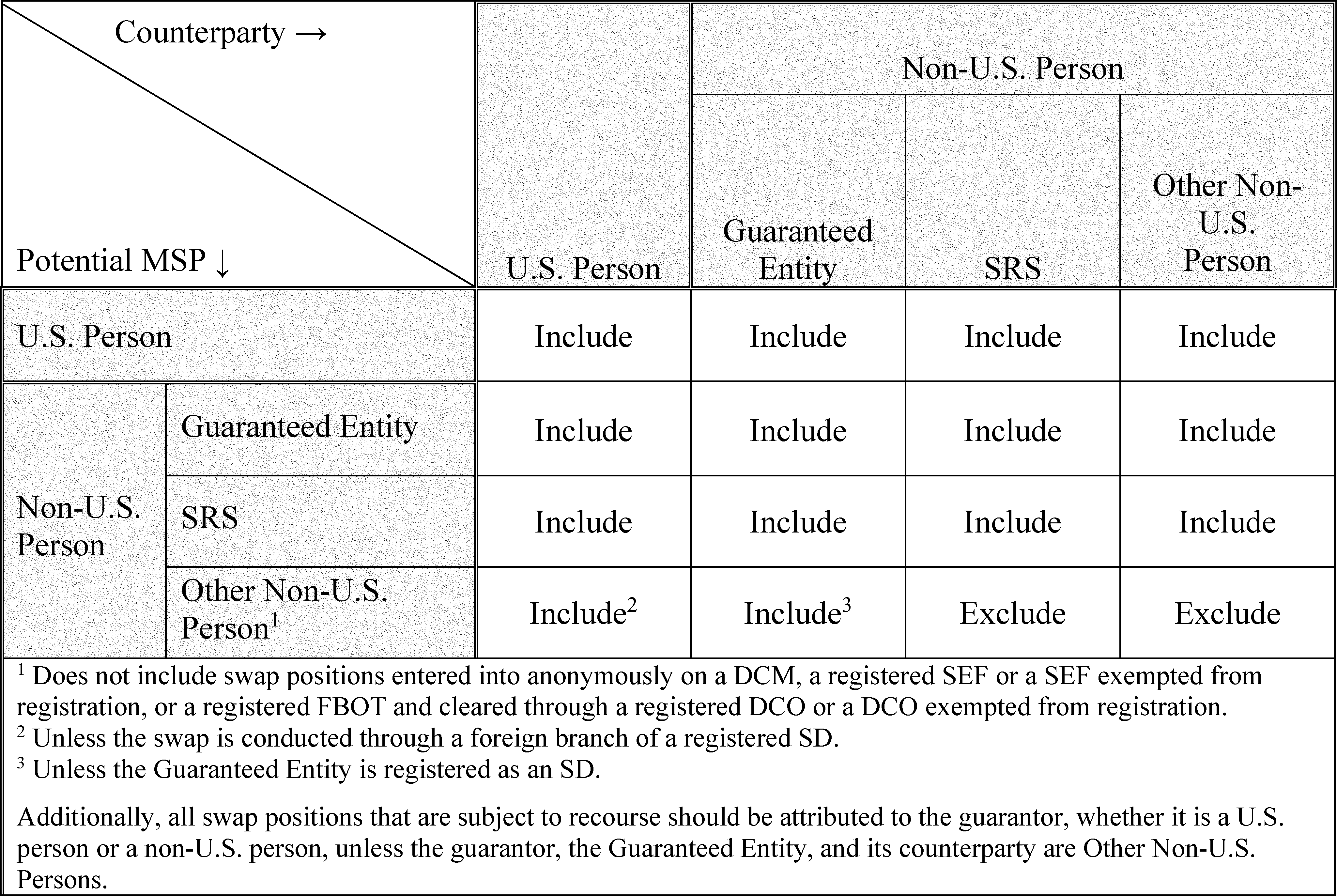

B. Table B—Cross-Border Application of the MSP Threshold

C. Table C—Cross-Border Application of the Group B Requirements in Consideration of Related Exceptions and Substituted Compliance

D. Table D—Cross-Border Application of the Group C Requirements in Consideration of Related Exceptions

I. Background

A. Statutory Authority and Prior Commission Action

In 2010, the Dodd-Frank Act [1] amended the CEA [2] to, among other things, establish a new regulatory framework for swaps. Added in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the Dodd-Frank Act was enacted to reduce systemic risk, increase transparency, and promote market integrity within the financial system. Given the global nature of the swap market, the Dodd-Frank Act amended the CEA by adding section 2(i) to provide that the swap provisions of the CEA enacted by Title VII of the Dodd-Frank Act (“Title VII”), including any rule prescribed or regulation promulgated under the CEA, shall not apply to activities outside the United States (“U.S.”) unless those activities have a direct and significant connection with activities in, or effect on, commerce of the United States, or they contravene Commission rules or regulations as are necessary or appropriate to prevent evasion of the swap provisions of the CEA enacted under Title VII.[3]

In May 2012, the CFTC and Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) jointly issued an adopting release that, among other things, further defined and provided registration thresholds for SDs and MSPs in § 1.3 of the CFTC's regulations (“Entities Rule”).[4]

In July 2013, the Commission published interpretive guidance and a policy statement regarding the cross-border application of certain swap provisions of the CEA (“Guidance”).[5] The Guidance included the Commission's interpretation of the “direct and significant” prong of section 2(i) of the CEA.[6] In addition, the Guidance established a general, non-binding framework for the cross-border application of many substantive Dodd-Frank Act requirements, including registration and business conduct requirements for SDs and MSPs, as well as a process for making substituted compliance determinations. Given the complex and dynamic nature of the global swap market, the Guidance was intended to be a flexible and efficient way to provide the Commission's views on cross-border issues raised by market participants, allowing the Commission to adapt in response to changes in the global regulatory and market landscape.[7] The Commission accordingly stated that it would review and modify its cross-border policies as the global swap market continued to evolve and consider codifying the cross-border application of the Dodd-Frank Act swap provisions in future rulemakings, as appropriate.[8] At the time that it adopted the Guidance, the Commission was tasked with regulating a market that grew to a global scale without any meaningful regulation in the United States or overseas, and the United States was the first member country of the Group of 20 (“G20”) to adopt most of the swap reforms agreed to at the G20 Pittsburgh Summit in 2009.[9] Developing a regulatory framework to fit that market necessarily requires adapting and responding to changes in the global market, including developments resulting from requirements imposed on market participants under the Dodd-Frank Act and the Commission's implementing regulations in the U.S., as well as those that have been imposed by non-U.S. regulatory authorities since the Guidance was issued.

On November 14, 2013, DSIO issued a staff advisory (“ANE Staff Advisory”) stating that a non-U.S. SD that regularly uses personnel or agents located in the United States to arrange, negotiate, or execute a swap with a non-U.S. person (“ANE Transactions”) would generally be required to comply with “Transaction-Level Requirements,” as the term was used in the Guidance (discussed in section V.A).[10] On November 26, 2013, Commission staff issued certain no-action relief to non-U.S. SDs registered with the Commission from these requirements in connection with ANE Transactions (“ANE No-Action Relief”).[11] In January 2014, the Commission published a request for comment on all aspects of the ANE Staff Advisory (“ANE Request for Comment”).[12]

In May 2016, the Commission issued a final rule on the cross-border application of the Commission's margin requirements for uncleared swaps (“Cross-Border Margin Rule”).[13] Among other things, the Cross-Border Margin Rule addressed the availability of substituted compliance by outlining the circumstances under which certain SDs and MSPs could satisfy the Commission's margin requirements for uncleared swaps by complying with comparable foreign margin requirements. The Cross-Border Margin Rule also established a framework by which the Commission assesses whether a foreign jurisdiction's margin requirements are comparable.

In October 2016, the Commission proposed regulations regarding the cross-border application of certain requirements under the Dodd-Frank Act regulatory framework for SDs and MSPs (“2016 Proposal”).[14] The 2016 Proposal incorporated various aspects of the Cross-Border Margin Rule and addressed when U.S. and non-U.S. persons, such as foreign consolidated subsidiaries (“FCSs”) and non-U.S. persons whose swap obligations are guaranteed by a U.S. person, would be required to include swaps or swap positions in their SD or MSP registration threshold calculations, respectively.[15] The 2016 Proposal also addressed the extent to which SDs and MSPs would be required to comply with the Commission's business conduct standards governing their conduct with swap counterparties (“external business conduct standards”) in cross-border transactions.[16] In addition, the 2016 Proposal addressed ANE Transactions, including the types of activities that would constitute arranging, negotiating, and executing within the context of the 2016 Proposal, the treatment of such transactions with respect to the SD registration threshold, and the application of external business conduct standards with respect to such transactions.[17]

B. Proposed Rule and Brief Summary of Comments Received

In January 2020, the Commission published a notice of proposed rulemaking (“Proposed Rule”), which proposed to: (1) Address the cross-border application of the registration thresholds and certain requirements applicable to SDs and MSPs; and (2) establish a formal process for requesting comparability determinations for such requirements from the Commission.[18] In the Proposed Rule, the Commission also withdrew the 2016 Proposal, stating that the Proposed Rule reflected the Commission's current views on the matters addressed in the 2016 Proposal, which had evolved since the 2016 Proposal as a result of market and regulatory developments in the swap markets and in the interest of international comity.[19] The Commission requested comments generally on all aspects of the Proposed Rule and on many specific questions.

The Commission received 18 relevant comment letters.[20] Though AFR and IATP did not support the Commission adopting the Proposed Rule in its entirety, most commenters were supportive of the Proposed Rule, generally, or supportive of specific elements of the Proposed Rule. However, many of these commenters suggested modifications to portions of the Proposed Rule, which are discussed in the relevant sections discussing the Final Rule below. In addition, several commenters requested Commission action beyond the scope of the Proposed Rule.[21] Further, IIB/SIFMA requested that the Commission re-visit in the Final Rule the applicability of the Commission's cross-border uncleared swap margin requirements that were addressed in the Cross-Border Margin Rule. The Commission addressed those requirements in the Cross-Border Margin Rule, did not propose modifying them in the Proposed Rule, and therefore is not making any changes to the Cross-Border Margin Rule in this Final Rule.

C. Global Regulatory and Market Structure

As noted in the Proposed Rule, the regulatory landscape is far different now than it was when the Dodd-Frank Act was enacted in 2010.[22] When the CFTC published the Guidance in 2013, very few jurisdictions had made significant progress in implementing the global swap reforms to which the G20 leaders agreed at the Pittsburgh G20 Summit. Today, however, as a result of the cumulative implementation efforts by regulators throughout the world, significant progress has been made in the world's primary swap trading jurisdictions to implement the G20 commitments.[23] Since the enactment of the Dodd-Frank Act, regulators in a number of large developed markets have adopted regulatory regimes that are designed to mitigate systemic risks associated with a global swap market. These regimes include central clearing requirements, margin requirements for non-centrally cleared derivatives, and other risk mitigation requirements.[24]

Many swaps involve at least one counterparty that is located in the United States or another jurisdiction that has adopted comprehensive swap regulations.[25] Conflicting and duplicative requirements between U.S. and foreign regimes can contribute to potential market inefficiencies and regulatory arbitrage, as well as competitive disparities that undermine the relative positions of U.S. SDs and their counterparties. This may result in market fragmentation, which can lead to significant inefficiencies that result in additional costs to end-users and other market participants. Market fragmentation can also reduce the capacity of financial firms to serve both domestic and international customers.[26] The Final Rule supports a cross-border framework that promotes the integrity, resilience, and vibrancy of the swap market while furthering the important policy goals of the Dodd-Frank Act. In that regard, it is important to consider how market practices have evolved since the publication of the Guidance. As certain market participants may have conformed their practices to the Guidance, the Final Rule will ideally cause limited additional costs and burdens for these market participants, while supporting the continued operation of markets that are much more comprehensively regulated than they were before the Dodd-Frank Act and the actions of governments worldwide taken in response to the Pittsburgh G20 Summit.

The approach described below is informed by the Commission's understanding of current market practices of global financial institutions under the Guidance. For business and regulatory reasons, a financial group that is active in the swap market often operates in multiple market centers around the world and carries out swap activity with geographically-diverse counterparties using a number of different operational structures.27Financial groups often prefer to operate their swap dealing businesses and manage their swap portfolios in the jurisdiction where the swaps and the underlying assets have the deepest and most liquid markets. In operating their swap dealing businesses in these market centers, financial groups seek to take advantage of expertise in products traded in those centers and obtain access to greater liquidity. These arrangements permit them to price products more efficiently and compete more effectively in the global swap market, including in jurisdictions different from the market center in which the swap is traded.

In this sense, a global financial enterprise effectively operates as a single business, with a highly integrated network of business lines and services conducted through various branches or affiliated legal entities that are under the control of the parent entity.[28] Branches and affiliates in a global financial enterprise are highly interdependent, with separate entities in the group providing financial or credit support to each other, such as in the form of a guarantee or the ability to transfer risk through inter-affiliate trades or other offsetting transactions. Even in the absence of an explicit arrangement or guarantee, a parent entity may, for reputational or other reasons, choose to assume the risk incurred by its affiliates located overseas. Swaps are also traded by an entity in one jurisdiction, but booked and risk-managed by an affiliate in another jurisdiction. The Final Rule recognizes that these and similar arrangements among global financial enterprises create channels through which swap-related risks can have a direct and significant connection with activities in, or effect on, commerce of the United States.

D. Interpretation of CEA Section 2(i)

1. Proposed Rule and Discussion of Comments

The Proposed Rule set forth the Commission's interpretation of CEA section 2(i), which mirrored the approach that the Commission took in the Guidance.

Several commenters provided their views on the Commission's interpretation of CEA section 2(i). Better Markets agreed with the Commission's description of the Commission's authority to regulate swaps activities outside of the United States, recognizing that CEA section 2(i)'s mandatory exclusion of only certain, limited non-U.S. activities (i.e., those that do not have a direct and significant connection with activities in, or effect on, U.S. commerce) evidences clear congressional intent to preserve jurisdiction with respect to others. Better Markets stated its belief that this reflects an intent to ensure U.S. law broadly applies to non-U.S. activities having requisite U.S. connections or effects. Better Markets argued, however, that the Commission does not have the discretion to determine whether and when to apply U.S. regulatory requirements based on vague principles of international comity, stating that the Commission has not cited a legally valid basis for its repeated reliance on international comity, where it simultaneously acknowledges direct and significant risks to the U.S. financial system.

BGC/Tradition supported the Commission's analysis related to CEA section 2(i) and what constitutes “direct and significant.” Specifically, BGC/Tradition agreed that the appropriate approach is “to apply the swap provisions of the CEA to activities outside the United States that have either: (1) A direct and significant effect on U.S. commerce; or, in the alternative, (2) a direct and significant connection with activities in U.S. commerce, and through such connection present the type of risks to the U.S. financial system and markets that Title VII directed the Commission to address.”

IIB/SIFMA discussed the Commission's interpretation of “direct” in CEA section 2(i) and argued that the Commission should have followed Supreme Court precedent interpreting the “direct effect” test found in the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976, which the Court has interpreted to be satisfied only by conduct abroad that has “an immediate consequence” in the United States.[29] IIB/SIFMA argued that a case cited by the Commission as a factor in its interpretation, the Seventh Circuit en banc decision in Minn-Chem, Inc. v. Agrium, Inc., was based on considerations that are relevant to the Foreign Trade Antitrust Improvements Act of 1982 (“FTAIA”),[30] —but not section 2(i)—namely that (a) because the FTAIA includes the word “foreseeable” along with “direct,” the word “direct” should be interpreted as part of an integrated phrase that includes “foreseeable” effects, and (b) the FTAIA already addresses foreign conduct that has an immediate consequence in the United States through its separate provision for import commerce.[31] But, IIB/SIFMA argued, CEA section 2(i) does not include the word “foreseeable,” nor does it include any other provisions addressing foreign conduct that have an immediate consequence within the United States, so the Minn-Chem Court's reasoning does not support the Commission's decision to discount the Supreme Court's interpretation of the word “direct” in Weltover.

IATP argued that the Commission did not provide a sufficient “international comity” argument to justify deviating from the plain meaning of “direct,” nor a sufficient argument to rely on FTAIA case law to interpret “direct.” IATP stated its belief that the Commission's reliance on cross-border anti-trust trade law to interpret its statutory authority under CEA section 2(i) is an inconsistent and unreliable foundation for a rule that proposes no measures to prevent or discipline SDs' unreasonable restraint of trade. IATP recommended that the Commission abandon its “restatement” of its CEA section 2(i) authority and rely on a plain reading of CEA section 2(i).

In response to Better Markets' contention that the Commission does not have the discretion to determine whether and when to apply U.S. regulatory requirements based on principles of international comity where it simultaneously acknowledges direct and significant risks to the U.S. financial system, the Commission has followed the Restatement of Foreign Relations law in striving to minimize conflicts with the laws of other jurisdictions while seeking, pursuant to CEA section 2(i), to apply the swaps requirements of Title VII to activities outside the United States that have a direct and significant connection with activities in, or effect on, U.S. commerce. The Commission has determined that the rule appropriately accounts for these competing interests, ensuring that the Commission can discharge its responsibilities to protect the U.S. markets, market participants, and financial system, consistent with international comity, as set forth in the Restatement.

With respect to IIB/SIFMA's contention that the Commission erred in its interpretation of the meaning of “direct” in CEA section 2(i), IIB/SIFMA incorrectly asserted that the Commission relied on the Seventh Circuit en banc decision in Minn-Chem, Inc. v. Agrium, Inc. Rather, the Commission was clear that its interpretation of CEA section 2(i) is not reliant on the reasoning of any individual judicial decision, but instead is drawn from a holistic understanding of both the statutory text and legal analysis applied by courts to analogous statutes and circumstances, specifically noting that the Commission's interpretation of CEA section 2(i) is not solely dependent on one's view of the Seventh Circuit's Minn-Chem decision,[32] but informed by its overall understanding of the relevant legal principles.

Finally, the Commission disagrees with IATP's advice that the Commission should abandon its interpretation of CEA section 2(i) and proceed with a “plain reading” of the statute. The Commission believes that IATP's assertion that the extraterritorial provisions of FTAIA and the case law construing such provisions are not relevant to CEA section 2(i) because the rule is not concerned with the regulation of anti-competitive behavior misconstrues the use that the Commission's interpretation has made of the Federal case law construing the meaning of the word “direct” in CEA section 2(i).[33]

2. Final Interpretation

In light of the foregoing, the Commission is restating its interpretation of section 2(i) of the CEA with its adoption of the Final Rule in substantially the same form as appeared in the Proposed Rule.

CEA section 2(i) provides that the swap provisions of Title VII shall not apply to activities outside the United States unless those activities—

- Have a direct and significant connection with activities in, or effect on, commerce of the United States; or

- Contravene such rules or regulations as the Commission may prescribe or promulgate as are necessary or appropriate to prevent the evasion of any provision of the CEA that was enacted by the Dodd-Frank Act.

The Commission believes that section 2(i) provides it express authority over swap activities outside the United States when certain conditions are met, but it does not require the Commission to extend its reach to the outer bounds of that authorization. Rather, in exercising its authority with respect to swap activities outside the United States, the Commission will be guided by international comity principles and will focus its authority on potential significant risks to the U.S. financial system.

(i) Statutory Analysis

In interpreting the phrase “direct and significant,” the Commission has examined the plain language of the statutory provision, similar language in other statutes with cross-border application, and the legislative history of section 2(i).

The statutory language in CEA section 2(i) is structured similarly to the statutory language in the FTAIA,[34] which provides the standard for the cross-border application of the Sherman Antitrust Act (“Sherman Act”).[35] The FTAIA, like CEA section 2(i), excludes certain non-U.S. commercial transactions from the reach of U.S. law. Specifically, the FTAIA provides that the antitrust provisions of the Sherman Act shall not apply to anti-competitive conduct involving trade or commerce with foreign nations.[36] However, like paragraph (1) of CEA section 2(i), the FTAIA also creates exceptions to the general exclusionary rule and thus brings back within antitrust coverage any conduct that: (1) Has a direct, substantial, and reasonably foreseeable effect on U.S. commerce; [37] and (2) such effect gives rise to a Sherman Act claim.[38] In F. Hoffman-LaRoche, Ltd. v. Empagran S.A., the U.S. Supreme Court stated that “this technical language initially lays down a general rule placing all (nonimport) activity involving foreign commerce outside the Sherman Act's reach. It then brings such conduct back within the Sherman Act's reach provided that the conduct both (1) sufficiently affects American commerce, i.e., it has a `direct, substantial, and reasonably foreseeable effect' on American domestic, import, or (certain) export commerce, and (2) has an effect of a kind that antitrust law considers harmful, i.e., the `effect' must `giv[e] rise to a [Sherman Act] claim.' ” [39]

It is appropriate, therefore, to read section 2(i) of the CEA as a clear expression of congressional intent that the swap provisions of Title VII of the Dodd-Frank Act apply to activities beyond the borders of the United States when certain circumstances are present.[40] These circumstances include, pursuant to paragraph (1) of section 2(i), when activities outside the United States meet the statutory test of having a “direct and significant connection with activities in, or effect on,” U.S. commerce.

An examination of the language in the FTAIA, however, does not provide an unambiguous roadmap for the Commission in interpreting section 2(i) of the CEA because there are both similarities, and a number of significant differences, between the language in CEA section 2(i) and the language in the FTAIA. Further, the Supreme Court has not provided definitive guidance as to the meaning of the direct, substantial, and reasonably foreseeable test in the FTAIA, and the lower courts have interpreted the individual terms in the FTAIA differently.

Although a number of courts have interpreted the various terms in the FTAIA, only the term “direct” appears in both CEA section 2(i) and the FTAIA.[41] Relying upon the Supreme Court's definition of the term “direct” in the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (“FSIA”),[42] the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit construed the term “direct” in the FTAIA as requiring a “relationship of logical causation,” [43] such that “an effect is `direct' if it follows as an immediate consequence of the defendant's activity.” [44] However, in an en banc decision, Minn-Chem, Inc. v. Agrium, Inc., the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit held that “the Ninth Circuit jumped too quickly on the assumption that the FSIA and the FTAIA use the word `direct' in the same way.” [45] After examining the text of the FTAIA as well as its history and purpose, the Seventh Circuit found persuasive the “other school of thought [that] has been articulated by the Department of Justice's Antitrust Division, which takes the position that, for FTAIA purposes, the term `direct' means only `a reasonably proximate causal nexus.' ” [46] The Seventh Circuit rejected interpretations of the term “direct” that included any requirement that the consequences be foreseeable, substantial, or immediate.[47] In 2014, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit followed the reasoning of the Seventh Circuit in the Minn-Chem decision.[48] That said, the Commission would like to make clear that its interpretation of CEA section 2(i) is not reliant on the reasoning of any individual judicial decision, but instead is drawn from a holistic understanding of both the statutory text and legal analysis applied by courts to analogous statutes and circumstances. In short, as the discussion below will illustrate, the Commission's interpretation of section 2(i) is not solely dependent on one's view of the Seventh Circuit's Minn-Chem decision, but informed by its overall understanding of the relevant legal principles.

Other terms in the FTAIA differ from the terms used in section 2(i) of the CEA. First, the FTAIA test explicitly requires that the effect on U.S. commerce be a “reasonably foreseeable” result of the conduct,[49] whereas section 2(i) of the CEA, by contrast, does not provide that the effect on U.S. commerce must be foreseeable. Second, whereas the FTAIA solely relies on the “effects” on U.S. commerce to determine cross-border application of the Sherman Act, section 2(i) of the CEA refers to both “effect” and “connection.” “The FTAIA says that the Sherman Act applies to foreign `conduct' with a certain kind of harmful domestic effect.” [50] Section 2(i), by contrast, applies more broadly—not only to particular instances of conduct that have an effect on U.S. commerce, but also to activities that have a direct and significant “connection with activities in” U.S. commerce. Unlike the FTAIA, section 2(i) applies the swap provisions of the CEA to activities outside the United States that have the requisite connection with activities in U.S. commerce, regardless of whether a “harmful domestic effect” has occurred.

As the foregoing textual analysis of the relevant statutory language indicates, section 2(i) differs from its analogue in the antitrust laws. Congress delineated the cross-border scope of the Sherman Act in section 6a of the FTAIA as applying to conduct that has a “direct,” “substantial,” and “reasonably foreseeable” “effect” on U.S. commerce. In section 2(i), on the other hand, Congress did not include a requirement that the effects or connections of the activities outside the United States be “reasonably foreseeable” for the Dodd-Frank Act swap provisions to apply. Further, Congress included language in section 2(i) to apply the Dodd-Frank Act swap provisions in circumstances in which there is a direct and significant connection with activities in U.S. commerce, regardless of whether there is an effect on U.S. commerce. The different words that Congress used in paragraph (1) of section 2(i), as compared to its closest statutory analogue in section 6a of the FTAIA, inform the Commission in construing the boundaries of its cross-border authority over swap activities under the CEA.[51] Accordingly, the Commission believes it is appropriate to interpret section 2(i) such that it applies to activities outside the United States in circumstances in addition to those that would be reached under the FTAIA standard.

One of the principal rationales for the Dodd-Frank Act was the need for a comprehensive scheme of systemic risk regulation. More particularly, a primary purpose of Title VII of the Dodd-Frank Act is to address risk to the U.S. financial system created by interconnections in the swap market.[52] Title VII of the Dodd-Frank Act gave the Commission new and broad authority to regulate the swap market to address and mitigate risks arising from swap activities that could adversely affect the resiliency of the financial system in the future.

In global markets, the source of such risk is not confined to activities within U.S. borders. Due to the interconnectedness between firms, traders, and markets in the U.S. and abroad, a firm's failure, or trading losses overseas, can quickly spill over to the United States and affect activities in U.S. commerce and the stability of the U.S. financial system. Accordingly, Congress explicitly provided for cross-border application of Title VII to activities outside the United States that pose risks to the U.S. financial system.[53] Therefore, the Commission construes section 2(i) to apply the swap provisions of the CEA to activities outside the United States that have either: (1) A direct and significant effect on U.S. commerce; or, in the alternative, (2) a direct and significant connection with activities in U.S. commerce, and through such connection present the type of risks to the U.S. financial system and markets that Title VII directed the Commission to address. The Commission interprets section 2(i) in a manner consistent with the overall goal of the Dodd-Frank Act to reduce risks to the resiliency and integrity of the U.S. financial system arising from swap market activities.[54] Consistent with this interpretation, the Commission interprets the term “direct” in section 2(i) to require a reasonably proximate causal nexus, and not to require foreseeability, substantiality, or immediacy.

Further, the Commission does not interpret section 2(i) to require a transaction-by-transaction determination that a specific swap outside the United States has a direct and significant connection with activities in, or effect on, commerce of the United States to apply the swap provisions of the CEA to such transaction. Rather, it is the connection of swap activities, viewed as a class or in the aggregate, to activities in commerce of the United States that must be assessed to determine whether application of the CEA swap provisions is warranted.[55]

Similar interpretations of other federal statutes regulating interstate commerce support the Commission's interpretation here. For example, the Supreme Court has long supported a similar “aggregate effects” approach when analyzing the reach of U.S. authority under the Commerce Clause.[56] The Court phrased the holding in the seminal “aggregate effects” decision, Wickard v. Filburn,[57] in this way: “[The farmer's] decision, when considered in the aggregate along with similar decisions of others, would have had a substantial effect on the interstate market for wheat.” [58] In another relevant decision, Gonzales v. Raich,[59] the Court adopted similar reasoning to uphold the application of the Controlled Substances Act [60] to prohibit the intrastate use of medical marijuana for medicinal purposes. In Raich, the Court held that Congress could regulate purely intrastate activity if the failure to do so would “leave a gaping hole” in the federal regulatory structure. These cases support the Commission's cross-border authority over swap activities that as a class, or in the aggregate, have a direct and significant connection with activities in, or effect on, U.S. commerce—whether or not an individual swap may satisfy the statutory standard.[61]

(ii) Principles of International Comity

Principles of international comity counsel the government in one country to act reasonably in exercising its jurisdiction with respect to activity that takes place in another country. Statutes should be construed to “avoid unreasonable interference with the sovereign authority of other nations.” [62] This rule of construction “reflects customary principles of international law” and “helps the potentially conflicting laws of different nations work together in harmony—a harmony particularly needed in today's highly interdependent commercial world.” [63]

The Restatement (Third) of Foreign Relations Law of the United States,[64] together with the Restatement (Fourth) of Foreign Relations Law of the United States [65] (collectively, the “Restatement”), states that a country has jurisdiction to prescribe law with respect to “conduct outside its territory that has or is intended to have substantial effect within its territory.” [66] The Restatement also counsels that even where a country has a basis for extraterritorial jurisdiction, it should not prescribe law with respect to a person or activity in another country when the exercise of such jurisdiction is unreasonable.[67]

As a general matter, the Fourth Restatement indicates that the concept of reasonableness as it relates to foreign relations law is “a principle of statutory interpretation” that “operates in conjunction with other principles of statutory interpretation.” [68] More specifically, the Fourth Restatement characterizes the inquiry into the reasonableness of exercising extraterritorial jurisdiction as an examination into whether “a genuine connection exists between the state seeking to regulate and the persons, property, or conduct being regulated.” [69] The Restatement explicitly indicates that the “genuine connection” between the state and the person, property, or conduct to be regulated can derive from the effects of the particular conduct or activities in question.[70]

Consistent with the Restatement, the Commission has carefully considered, among other things, the level of the foreign jurisdiction's supervisory interests over the subject activity and the extent to which the activity takes place within the foreign territory. In doing so, the Commission has strived to minimize conflicts with the laws of other jurisdictions while seeking, pursuant to section 2(i), to apply the swaps requirements of Title VII to activities outside the United States that have a direct and significant connection with activities in, or effect on, U.S. commerce.

The Commission believes the Final Rule appropriately accounts for these competing interests, ensuring that the Commission can discharge its responsibilities to protect the U.S. markets, market participants, and financial system, consistent with international comity, as set forth in the Restatement. Of particular relevance is the Commission's approach to substituted compliance in the Final Rule, which mitigates burdens associated with potentially conflicting foreign laws and regulations in light of the supervisory interests of foreign regulators in entities domiciled and operating in their own jurisdictions.

E. Final Rule

The Final Rule identifies which cross-border swaps or swap positions a person will need to consider when determining whether it needs to register with the Commission as an SD or MSP, as well as related classifications of swap market participants and swaps (e.g., U.S. person, foreign branch, swap conducted through a foreign branch).[71] Further, the Commission is adopting several tailored exceptions from, and a substituted compliance process for, certain regulations applicable to registered SDs and MSPs. The Final Rule also creates a framework for comparability determinations for such regulations that emphasizes a holistic, outcomes-based approach that is grounded in principles of international comity. Finally, the Final Rule requires SDs and MSPs to create a record of their compliance with the Final Rule and to retain such records in accordance with § 23.203.[72] The Final Rule supersedes the Commission's policy views as set forth in the Guidance with respect to its interpretation and application of section 2(i) of the CEA and the swap provisions addressed in the Final Rule.[73]

Some commenters provided their views on the Proposed Rule generally. AFR and IATP both argued that, in sum, the Proposed Rule would fatally weaken the implementation of Title VII of the Dodd-Frank Act and its application to CFTC-regulated derivatives markets, and urged the Commission to step back from the course outlined in the Proposed Rule and restore elements of the Guidance and the 2016 Proposal that, they maintained, offered better oversight of derivatives markets. The Commission has considered these comments but believes that the Final Rule generally reflects the approach outlined by the Commission in the Guidance, and has determined that it takes account of conflicts with the laws of other jurisdictions when applying the swaps requirements of Title VII to activities outside the United States that have a direct and significant connection with activities in, or effect on, U.S. commerce, permitting the Commission to discharge its responsibilities to protect the U.S. markets, market participants, and financial system, consistent with international comity.

More specifically, the Final Rule takes into account the Commission's experience implementing the Dodd-Frank Act reforms, including its experience with the Guidance and the Cross-Border Margin Rule, comments submitted in connection with the ANE Request for Comment and the Proposed Rule, as well as discussions that the Commission and its staff have had with market participants,[74] other domestic [75] and foreign regulators, and other interested parties. It is essential that a cross-border framework recognize the global nature of the swap market and the supervisory interests of foreign regulators with respect to entities and transactions covered by the Commission's swap regime. In determining the extent to which the Dodd-Frank Act swap provisions addressed by the Final Rule apply to activities outside the United States, the Commission has strived to protect U.S. interests as contemplated by Congress in Title VII, and minimize conflicts with the laws of other jurisdictions. The Commission has carefully considered, among other things, the level of a home jurisdiction's supervisory interests over the subject activity and the extent to which the activity takes place within the home country's territory.[76] At the same time, the Commission has also considered the potential for cross-border activities to have a significant connection with activities in, or effect on, commerce of the United States, as well as the global, highly integrated nature of today's swap markets.

To fulfill the purposes of the Dodd-Frank Act swap reforms, the Commission's supervisory oversight cannot be confined to activities strictly within the territory of the United States. Rather, the Commission will exercise its supervisory authority outside the United States in order to reduce risk to the resiliency and integrity of the U.S. financial system.[77] The Commission will also strive to show deference to non-U.S. regulation when such regulation achieves comparable outcomes to mitigate unnecessary conflict with effective non-U.S. regulatory frameworks and limits fragmentation of the global marketplace.

The Commission has also sought to target those classes of entities whose activities—due to the nature of their relationship with a U.S. person or U.S. commerce—most clearly present the risks addressed by the Dodd-Frank Act provisions, and related regulations covered by the Final Rule. The Final Rule is designed to limit opportunities for regulatory arbitrage by applying the registration thresholds in a consistent manner to differing organizational structures that serve similar economic functions or have similar economic effects. At the same time, the Commission is mindful of the effect of its choices on market efficiency and competition, as well as the importance of international comity when exercising the Commission's authority. The Commission believes that the Final Rule reflects a measured approach that advances the goals underlying SD and MSP regulation, consistent with the Commission's statutory authority, while mitigating market distortions and inefficiencies, and avoiding fragmentation.

II. Key Definitions

The Commission is adopting definitions for certain terms for the purpose of applying the Dodd-Frank Act swap provisions addressed by the Final Rule to cross-border transactions. Certain of these definitions are relevant in assessing whether a person's activities have the requisite “direct and significant” connection with activities in, or effect on, U.S. commerce within the meaning of CEA section 2(i). Specifically, the definitions are relevant in determining whether certain swaps or swap positions need to be counted toward a person's SD or MSP threshold and in addressing the cross-border application of certain Dodd-Frank Act requirements (as discussed below in sections III through VII).

A. Reliance on Representations—Generally

The Commission acknowledges that the information necessary for a swap counterparty to accurately assess whether its counterparty or a specific swap meets one or more of the definitions discussed below may be unavailable, or available only through overly burdensome due diligence. For this reason, the Commission believes that a market participant should generally be permitted to reasonably rely on written counterparty representations in each of these respects.[78] Therefore, the Commission proposed that a person may rely on a written representation from its counterparty that the counterparty does or does not satisfy the criteria for one or more of the definitions below, unless such person knows or has reason to know that the representation is not accurate.[79] AFEX/GPS supported the proposed written representation language and noted that it would facilitate compliance with the rules.

The Commission is adopting the “reliance on representations” language as proposed.[80] For the purposes of this rule, a person would have reason to know the representation is not accurate if a reasonable person should know, under all of the facts of which the person is aware, that it is not accurate. This language is consistent with: (1) The reliance standard articulated in the Commission's external business conduct rules; [81] (2) the Commission's approach in the Cross-Border Margin Rule; [82] and (3) the reliance standard articulated in the “U.S. person” and “transaction conducted through a foreign branch” definitions adopted by the SEC in its rule addressing the regulation of cross-border securities-based swap activities (“SEC Cross-Border Rule”).[83] A number of commenters also specifically addressed reliance on representations obtained under the Cross-Border Margin Rule or the Guidance for the “U.S. person” and “Guarantee” definitions. These comments are addressed below in sections II.B.5 and II.C.

B. U.S. Person, Non-U.S. Person, and United States

1. Generally

(i) Proposed Rule

As discussed in more detail below, the Commission proposed defining “U.S. person” consistent with the definition of “U.S. person” in the SEC Cross-Border Rule.[84] The proposed definition of “U.S. person” was also consistent with the Commission's statutory mandate under the CEA, and in this regard was largely consistent with the definition of “U.S. person” in the Cross-Border Margin Rule.[85] Specifically, the Commission proposed to define “U.S. person” as:

(1) A natural person resident in the United States;

(2) A partnership, corporation, trust, investment vehicle, or other legal person organized, incorporated, or established under the laws of the United States or having its principal place of business in the United States;

(3) An account (whether discretionary or non-discretionary) of a U.S. person; or

(4) An estate of a decedent who was a resident of the United States at the time of death.[86]

As noted in the Cross-Border Margin Rule,[87] and consistent with the SEC [88] definition of “U.S. person,” proposed § 23.23(a)(22)(ii) provided that the principal place of business means the location from which the officers, partners, or managers of the legal person primarily direct, control, and coordinate the activities of the legal person. Consistent with the SEC, the Commission noted that the principal place of business for a collective investment vehicle (“CIV”) would be in the United States if the senior personnel responsible for the implementation of the CIV's investment strategy are located in the United States, depending on the facts and circumstances that are relevant to determining the center of direction, control, and coordination of the CIV.[89]

Additionally, in consideration of the discretionary and appropriate exercise of international comity-based doctrines, proposed § 23.23(a)(22)(iii) stated that the term “U.S. person” would not include certain international financial institutions.[90] Specifically, consistent with the SEC's definition,[91] the term U.S. person would not include the International Monetary Fund, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the Inter-American Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the African Development Bank, the United Nations, and their agencies and pension plans, and any other similar international organizations, their agencies, and pension plans.

Further, to provide certainty to market participants, proposed § 23.23(a)(22)(iv) permitted reliance, until December 31, 2025, on any U.S. person-related representations that were obtained to comply with the Cross-Border Margin Rule.[92]

(ii) Summary of Comments

In general, AIMA, AFEX/GPS, Barnard, Chatham, CS, IIB/SIFMA, JFMC/IBAJ, JBA, JSCC, and State Street supported the proposed “U.S. person” definition, while IATP generally opposed the proposed definition. Additional comments and suggestions are discussed below.

AIMA, Barnard,[93] Chatham, CS, IIB/SIFMA, JFMC/IBAJ, JSCC, and State Street generally supported the Commission's view that aligning with the SEC's definition of “U.S. person” provided consistency to market participants, noting that the harmonized definition would: (1) Provide a consistent approach from operational and compliance perspectives; (2) help avoid undue regulatory complexity for purposes of firms' swaps and security-based swaps businesses; and/or (3) simplify market practice and reduce complexity. AFEX/GPS, Chatham, CS, JFMC/IBAJ, JSCC, and State Street generally stated that the simpler and streamlined prongs in the proposed “U.S. person” definition allowed for more straightforward application of the definition as compared to the Guidance. Chatham also noted that the proposed definition of “U.S. person” establishes a significant nexus to the United States.

FIA recommended that the Commission explicitly state that the scope of the proposed definition of a “U.S. person” would not extend to provisions of the CEA governing futures commission merchants (“FCMs”) with respect to both: (1) Exchange-traded futures, whether executed on a designated contract market or a foreign board of trade; and (2) cleared swaps.

IATP suggested restoring the “U.S. person” definition from the Guidance and 2016 Proposal. IATP argued that the SEC definition applies to the relatively small universe of security-based swaps, and therefore, the Commission should adopt the “U.S. person” and other definitions from the 2016 Proposal for the much larger universe of physical and financial commodity swaps the Commission is authorized to regulate. IATP also asserted that adopting the SEC definition for harmonization purposes was not necessary because SDs and MSPs should have the personnel and information technology resources to comply effectively with reporting and recordkeeping of swaps and security-based swaps. Further, any reduced efficiency would be compensated for by having the “U.S. person” definition apply not only to enumerated entities but to a non-exhaustive listing that anticipates the creation of new legal entities engaged in swaps activities.

(iii) Final Rule

As discussed in more detail below, the Commission is adopting the “U.S. person” definition as proposed, with certain clarifications.[94] In response to IATP, the Commission continues to be of the view that harmonization of the “U.S. person” definition with the SEC is the appropriate approach given that it is straightforward to apply compared to the Guidance definition, and will capture substantially the same types of entities as the “U.S. person” definition in the Cross-Border Margin Rule.[95] In addition, harmonizing with the definition in the SEC Cross-Border Rule is not only consistent with section 2(i) of the CEA,[96] but is also expected to reduce undue compliance costs for market participants. Therefore, as noted by several commenters, the definition will reduce complexity for entities that are participants in the swaps and security-based swaps markets and may register both as SDs with the Commission and as security-based swap dealers with the SEC. The Commission is also of the view that the “U.S. person” definition in the Cross-Border Margin Rule largely encompasses the same universe of persons as the definition used in the SEC Cross-Border Rule and the Final Rule.[97]

In response to FIA, pursuant to § 23.23(a), “U.S. person” only has the meaning in the definition for the purposes of § 23.23. However, to be clear that the definition of “U.S. person” is only applicable for purposes of the Final Rule, the rule now includes the word “solely” and reads “Solely for purposes of this section . . . .”

Generally, the Commission believes that the definition offers a clear, objective basis for determining which individuals or entities should be identified as U.S. persons for purposes of the swap requirements addressed by the Final Rule. Specifically, the various prongs, as discussed in more detail below, are intended to identify persons whose activities have a significant nexus to the United States by virtue of their organization or domicile in the United States.[98]

Additionally, the Commission is adopting as proposed the definitions for “non-U.S. person,” “United States,” and “U.S.” The term “non-U.S. person” means any person that is not a U.S. person.[99] Further, the Final Rule defines “United States” and “U.S.” as the United States of America, its territories and possessions, any State of the United States, and the District of Columbia.[100] The Commission did not receive any comments regarding these definitions.

2. Prongs

As the Commission noted in the Proposed Rule, paragraph (i) of the “U.S. person” definition identifies certain persons as a “U.S. person” by virtue of their domicile or organization within the United States.[101] The Commission has traditionally looked to where legal entities are organized or incorporated (or in the case of natural persons, where they reside) to determine whether they are U.S. persons.[102] In the Commission's view, these persons—by virtue of their decision to organize or locate in the United States and because they are likely to have significant financial and legal relationships in the United States—are appropriately included within the definition of “U.S. person.” [103]

(i) § 23.23(a)(23)(i)(A) and (B)

Paragraphs (i)(A) and (B) of the “U.S. person” definition generally incorporate a “territorial” concept of a U.S. person.[104] That is, these are natural persons and legal entities that are physically located or incorporated within U.S. territory, and thus are subject to the Commission's jurisdiction. Further, the Commission generally considers swap activities where such persons are counterparties, as a class and in the aggregate, as satisfying the “direct and significant” test under CEA section 2(i). Consistent with the “U.S. person” definition in the Cross-Border Margin Rule [105] and the SEC Cross-Border Rule,[106] the definition encompasses both foreign and domestic branches of an entity. As discussed below, a branch does not have a legal identity apart from its principal entity.[107]

The first prong of the proposed definition stated that a natural person resident in the United States would be considered a U.S. person. No comments were received regarding the first prong of the “U.S. person” definition and the Commission is adopting it as proposed.[108]

The second prong of the proposed definition stated that a partnership, corporation, trust, investment vehicle, or other legal person organized, incorporated, or established under the laws of the United States or having its principal place of business in the United States would be considered a U.S. person. In the Proposed Rule, the Commission stated that the second prong of the definition would subsume the pension fund and trust prongs of the “U.S. person” definition in the Cross-Border Margin Rule.[109] No comments were received regarding this aspect of the Proposed Rule and the Commission is adopting it as proposed.[110]

Specifically, the Commission is of the view that, as adopted, § 23.23(a)(23)(i)(B) includes in the definition of the term “U.S. person” pension plans for the employees, officers, or principals of a legal entity described in § 23.23(a)(23)(i)(B), which is a separate prong in the Cross-Border Margin Rule.[111] Although the SEC Cross-Border Rule directly addresses pension funds only in the context of international financial institutions, discussed below, the Commission believes it is important to clarify that pension funds in other contexts could meet the requirements of § 23.23(a)(23)(i)(B).[112]

Additionally, § 23.23(a)(23)(i)(B) subsumes the trust prong of the “U.S. person” definition in the Cross-Border Margin Rule.[113] With respect to trusts addressed in § 23.23(a)(23)(i)(B), the Commission expects that its approach is consistent with the manner in which trusts are treated for other purposes under the law. The Commission has considered that each trust is governed by the laws of a particular jurisdiction, which may depend on steps taken when the trust was created or other circumstances surrounding the trust. The Commission believes that if a trust is governed by U.S. law (i.e., the law of a state or other jurisdiction in the United States), then it is generally reasonable to treat the trust as a U.S. person for purposes of the Final Rule. Another relevant element in this regard is whether a court within the United States is able to exercise primary supervision over the administration of the trust. The Commission expects that this aspect of the definition generally aligns the treatment of the trust for purposes of the Final Rule with how the trust is treated for other legal purposes. For example, the Commission expects that if a person could bring suit against the trustee for breach of fiduciary duty in a U.S. court (and, as noted above, the trust is governed by U.S. law), then treating the trust as a U.S. person is generally consistent with its treatment for other purposes.[114]

(ii) § 23.23(a)(23)(i)(D)

Under the fourth prong of the proposed definition, an estate of a decedent who was a resident of the United States at the time of death would be included in the definition of “U.S. person.” No comments were received regarding this aspect of the Proposed Rule and the Commission is adopting it as proposed.[115] With respect to § 23.23(a)(23)(i)(D), the Commission believes that the swaps of a decedent's estate should generally be treated the same as the swaps entered into by the decedent during their life.[116] If the decedent was a party to any swaps at the time of death, then those swaps should generally continue to be treated in the same way after the decedent's death, at which time the swaps would most likely pass to the decedent's estate. Also, the Commission expects that this prong will be predictable and straightforward to apply for natural persons planning for how their swaps will be treated after death, for executors and administrators of estates, and for the swap counterparties to natural persons and estates.

(iii) § 23.23(a)(23)(i)(C)

The third prong of the definition, the “account” prong, was proposed to ensure that persons described in prongs (A), (B), and (D) of the definition would be treated as U.S. persons even if they use discretionary or non-discretionary accounts to enter into swaps, irrespective of whether the person at which the account is held or maintained is a U.S. person.[117] Consistent with the Cross-Border Margin Rule, the Commission stated that this prong would apply for individual or joint accounts.[118] IIB/SIFMA recommended that, consistent with the SEC, the Commission clarify that under the “account” prong of the definition, an account's U.S. person status should depend on whether any U.S.-person owner of the account actually incurs obligations under the swap in question.

The Commission is adopting this aspect of the U.S. person definition as proposed, with a clarification.[119] In response to the IIB/SIFMA comment, the Commission is clarifying that an account's U.S. person status depends on whether any U.S. person owner of the account actually incurs obligations under the swap in question. Consistent with the SEC Cross-Border Rule, where an account is owned by both U.S. persons and non-U.S. persons, the U.S.-person status of the account, as a general matter, turns on whether any U.S.-person owner of the account incurs obligations under the swap.[120] Neither the status of the fiduciary or other person managing the account, nor the discretionary or non-discretionary nature of the account, nor the status of the person at which the account is held or maintained, are relevant in determining the account's U.S.-person status.

(iv) Exclusion of Unlimited U.S. Responsibility Prong

Unlike the Cross-Border Margin Rule, the proposed definition of “U.S. person” did not include certain legal entities that are owned by one or more U.S. person(s) and for which such person(s) bear unlimited responsibility for the obligations and liabilities of the legal entity (“unlimited U.S. responsibility” prong).[121] The Commission invited comment on whether it should include an unlimited U.S. responsibility prong in the definition of “U.S. person,” and if not, whether it should revise its interpretation of “guarantee” in a manner consistent with the SEC such that persons that would have been considered U.S. persons pursuant to an unlimited U.S. responsibility prong would instead be considered entities with guarantees from a U.S. person.[122]

Chatham and IIB/SIFMA agreed that the Commission should not include an unlimited U.S. responsibility prong in the “U.S. Person” definition, noting that the persons that would be captured under the prong are corporate structures that are not commonly in use in the marketplace (e.g., unlimited liability corporations, general partnerships, and sole proprietorships). IIB/SIFMA added that to the extent a firm uses this structure, the Commission can sufficiently address the resulting risks to the United States by treating the firm as having a guarantee from a U.S. person, as the SEC does.

The Commission is adopting as proposed a definition of “U.S. person” that does not include an unlimited U.S. responsibility prong. Although this corporate structure may exist in some limited form, the Commission does not believe that justifies the cost of classification as a “U.S. person.” This prong was designed to capture persons that could give rise to risk to the U.S. financial system in the same manner as with non-U.S. persons whose swap transactions are subject to explicit financial support arrangements from U.S. persons.[123] Rather than including this prong in its “U.S. person” definition, the SEC took the view that when a non-U.S. person's counterparty has recourse to a U.S. person for the performance of the non-U.S. person's obligations under a security-based swap by virtue of the U.S. person's unlimited responsibility for the non-U.S. person, the non-U.S. person would be required to include the security-based swap in its security-based swap dealer (if it is a dealing security-based swap) and major security-based swap participant threshold calculations as a guarantee.[124] Therefore, as discussed below with respect to the definition of “guarantee,” the Commission is clarifying that legal entities that are owned by one or more U.S. person(s) and for which such person(s) bear unlimited responsibility for the obligations and liabilities will be considered as having a guarantee from a U.S. person, similar to the approach in the SEC Cross-Border Rule. The CFTC's anti-evasion rules address concerns that persons may structure transactions to avoid classification as a U.S. person.[125]

The treatment of the unlimited U.S. liability prong in the Final Rule does not affect an entity's obligations with respect to the Cross-Border Margin Rule. To the extent that entities are considered U.S. persons for purposes of the Cross-Border Margin Rule as a result of the unlimited U.S. liability prong, the Commission believes that the different purpose of the registration-related rules justifies this potentially different treatment.[126]

(v) Exclusion of Collective Investment Vehicle Prong

Consistent with the definition of “U.S. person” in the Cross-Border Margin Rule and the SEC Cross-Border Rule, the proposed definition did not include a commodity pool, pooled account, investment fund, or other CIV that is majority-owned by one or more U.S. persons.[127] This prong was included in the Guidance definition. The Commission invited comment on whether it is appropriate that commodity pools, pooled accounts, investment funds, or other CIVs that are majority-owned by U.S. persons would not be included in the proposed definition of “U.S. person.” [128]

AIMA, Chatham, IIB/SIFMA, JFMC/IBAJ,[129] JBA, and State Street supported not including this prong in the “U.S. person” definition. They generally noted that there are practical difficulties in tracking the beneficial ownership in CIVs, and therefore, including a CIV prong would increase the complexity of the “U.S. person” definition. AIMA stated that this could necessitate conservative assumptions being made to avoid the risk of breaching regulatory requirements that depend on the status of investors in the vehicle. JBA noted that non-U.S. persons may choose not to enter into transactions with CIVs in which U.S. persons are involved to avoid the practical burdens of identifying and tracking the beneficial ownership of funds in real-time and the excessive cost arising from the registration threshold calculations. JFMC/IBAJ elaborated that ownership composition can change throughout the life of the vehicle due to redemptions and additional investments.

AIMA, Chatham, and State Street also noted that there are limited benefits to including a requirement to “look-through” non-U.S. CIVs to identify and track U.S. beneficial owners of such vehicles. AIMA stated that it is reasonable to assume that the potential investment losses to which U.S. investors in CIVs are exposed are limited to their initial capital investment. Chatham stated that the composition of a CIV's beneficial owners is not likely to have a significant bearing on the degree of risk that the CIV's swap activity poses to the U.S. financial system, noting that CIVs organized or having a principal place of business in the U.S. would be under the Commission's authority, and majority-owned CIVs may be subject to margin requirements in foreign jurisdictions.

AIMA added that the definition of “U.S. person” in the Guidance is problematic for certain funds managed by investment managers because they are subject to European rules on clearing, margining, and risk mitigation.

After consideration of the comments, and consistent with the definition of “U.S. person” in the Cross-Border Margin Rule and the SEC Cross-Border Rule, the Commission is adopting as proposed a “U.S. person” definition that does not include a commodity pool, pooled account, investment fund, or other CIV that is majority-owned by one or more U.S. persons.[130] Similar to the SEC, the Commission is of the view that including majority-owned CIVs within the definition of “U.S. person” for the purposes of the Final Rule would likely cause more CIVs to incur additional programmatic costs associated with the relevant Title VII requirements and ongoing assessments, while not significantly increasing programmatic benefits given that the composition of a CIV's beneficial owners is not likely to have significant bearing on the degree of risk that the CIV's swap activity poses to the U.S. financial system.[131] Although many of these CIVs have U.S. participants that could be adversely affected in the event of a counterparty default, systemic risk concerns are mitigated to the extent these CIVs are subject to margin requirements in foreign jurisdictions. In addition, the exposure of participants to losses in CIVs is typically limited to their investment amount, and it is unlikely that a participant in a CIV would make counterparties whole in the event of a default.[132] Further, the Commission continues to believe that identifying and tracking a CIV's beneficial ownership may pose a significant challenge, particularly in certain circumstances such as fund-of-funds or master-feeder structures.[133] Therefore, although the U.S. participants in such CIVs may be adversely affected in the event of a counterparty default, the Commission has determined that the majority-ownership test should not be included in the definition of “U.S. person.”

A CIV fitting within the majority U.S. ownership prong may also be a U.S. person within the scope of § 23.23(a)(23)(i)(B) of the Final Rule (entities organized or having a principal place of business in the United States). As the Commission clarified in the Cross-Border Margin Rule, whether a pool, fund, or other CIV is publicly offered only to non-U.S. persons and not offered to U.S. persons is not relevant in determining whether it falls within the scope of the “U.S. person” definition.[134]

(vi) Exclusion of Catch-All Prong

Unlike the non-exhaustive “U.S. person” definition provided in the Guidance,[135] the Commission proposed that the definition of “U.S. person” be limited to persons enumerated in the rule, consistent with the Cross-Border Margin Rule and the SEC Cross-Border Rule.[136] The Commission invited comment on whether the “U.S. person” definition should include a catch-all provision.[137]

AFEX/GPS, Chatham, IIB/SIFMA, and JBA supported elimination of the “include, but not limited to” language from the Guidance. AFEX/GPS stated that this approach should help facilitate compliance with Commission rules. Chatham stated that the catch-all prong works against the core purposes of the cross-border rules, to enhance regulatory cooperation and transparency. IIB/SIFMA stated that market participants have lacked any practical way to delineate the scope of that catch-all phrase, leading to legal uncertainty. JBA stated that the provision is difficult to interpret and leads to uncertainty, and potentially reduced transactions by market participants, leading to increased bifurcation in the market.

The Commission is adopting this aspect of the “U.S. person” definition as proposed.[138] Unlike the non-exhaustive “U.S. person” definition provided in the Guidance, the definition of “U.S. person” is limited to persons enumerated in the rule, consistent with the Cross-Border Margin Rule and the SEC Cross-Border Rule.[139] The Commission believes that the prongs adopted in the Final Rule capture those persons with sufficient jurisdictional nexus to the U.S. financial system and commerce in the United States that they should be categorized as “U.S. persons.” [140]

3. Principal Place of Business

The Commission proposed to define “principal place of business” as the location from which the officers, partners, or managers of the legal person primarily direct, control, and coordinate the activities of the legal person, consistent with the SEC definition of “U.S. person.” [141] Additionally, with respect to a CIV, the Proposed Rule stated that this location is the office from which the manager of the CIV primarily directs, controls, and coordinates the investment activities of the CIV, and noted that activities such as formation of the CIV, absent an ongoing role by the person performing those activities in directing, controlling, and coordinating the investment activities of the CIV, generally would not be as indicative of activities, financial and legal relationships, and risks within the United States of the type that Title VII is intended to address as the location of a CIV manager.[142] The Commission invited comment on whether, when determining the principal place of business for a CIV, the Commission should consider including as a factor whether the senior personnel responsible for the formation and promotion of the CIV are located in the United States, similar to the approach in the Cross-Border Margin Rule.[143]

AIMA supported the proposed definition of “principal place of business” and stated that there are more relevant indicia of U.S. nexus than the activities of forming and promoting a CIV, such as the location of staff who control the investment activities of the CIV. Similarly, IIB/SIFMA supported adopting the SEC's “principal place of business” test for CIVs because it better captures business reality by focusing more on investment strategy rather than the location of promoters who do not have an ongoing responsibility for the vehicle.

The Commission is adopting the “principal place of business” aspect of the “U.S. person” definition as proposed.[144] As noted in the Cross-Border Margin Rule,[145] and consistent with the SEC definition of “U.S. person,” [146] § 23.23(a)(23)(ii) provides that the principal place of business means the location from which the officers, partners, or managers of the legal person primarily direct, control, and coordinate the activities of the legal person. With the exception of externally managed entities, as discussed below, the Commission is of the view that for most entities, the location of these officers, partners, or managers generally corresponds to the location of the person's headquarters or main office. However, the Commission believes that a definition that focuses exclusively on whether a legal person is organized, incorporated, or established in the United States could encourage some entities to move their place of incorporation to a non-U.S. jurisdiction to avoid complying with the relevant Dodd-Frank Act requirements, while maintaining their principal place of business—and therefore, risks arising from their swap transactions—in the United States. Moreover, a “U.S. person” definition that does not include a “principal place of business” element could result in certain entities falling outside the scope of the relevant Dodd-Frank Act-related requirements, even though the nature of their legal and financial relationships in the United States is, as a general matter, indistinguishable from that of entities incorporated, organized, or established in the United States. Therefore, the Commission is of the view that it is appropriate to treat such entities as U.S. persons for purposes of the Final Rule.[147]

However, determining the principal place of business of a CIV, such as an investment fund or commodity pool, may require consideration of additional factors beyond those applicable to operating companies.[148] The Commission interprets that, for an externally managed investment vehicle, this location is the office from which the manager of the vehicle primarily directs, controls, and coordinates the investment activities of the vehicle.[149] This interpretation is consistent with the Supreme Court's decision in Hertz Corp. v. Friend, which described a corporation's principal place of business, for purposes of diversity jurisdiction, as the “place where the corporation's high level officers direct, control, and coordinate the corporation's activities.” [150] In the case of a CIV, the senior personnel that direct, control, and coordinate a CIV's activities are generally not the named directors or officers of the CIV, but rather persons employed by the CIV's investment advisor or promoter, or in the case of a commodity pool, its CPO. Therefore, consistent with the SEC Cross-Border Rule,[151] when a primary manager is responsible for directing, controlling, and coordinating the overall activity of a CIV, the CIV's principal place of business under the Final Rule is the location from which the manager carries out those responsibilities.

Under the Cross-Border Margin Rule,[152] the Commission generally considers the principal place of business of a CIV to be in the United States if the senior personnel responsible for either: (1) The formation and promotion of the CIV; or (2) the implementation of the CIV's investment strategy are located in the United States, depending on the facts and circumstances that are relevant to determining the center of direction, control, and coordination of the CIV. Although the second prong is consistent with the approach discussed above, the Commission does not believe that activities such as formation of the CIV, absent an ongoing role by the person performing those activities in directing, controlling, and coordinating the investment activities of the CIV, generally will be as indicative of activities, financial and legal relationships, and risks within the United States of the type that Title VII is intended to address as the location of a CIV manager.[153] The Commission may also consider amending the “U.S. person” definition in the Cross-Border Margin Rule in the future.

4. Exception for International Financial Institutions